A brief history of Photography and Progress

common ground

The link between photography and industrial society dates back to the very birth of the medium and coincides with the spread of the particular Spirit of the nineteenth-twentieth century that placed technological progress at the core of human civilization.

The invention of photography is indeed not the result of individual and sudden inventiveness but the product of studies and entrepreneurial initiative of different players who shared the need to mechanize the production of images alongside that of goods and artifacts.

All of them, rather than photographers or artists were inventors, entrepreneurs, “modern” men, driven by that spirit an idea of Progress..

Joseph-Nicéphore Niepce, one of the pioneers of the photographic process (which he first experimented with in 1827), had also invented with his brother Claude a steam engine that they had used to move a river boat. He was interested in the possibility of fixing the image “photographically” because he wanted to apply the invention to the engraving process, very popular in France in publishing and crafts.

Thomas Wedgewood was already experimenting with sunlight printing around 1800 to try to serialize the printing of decorative images on the products of the family company, the famous Wedgewood Pottery.

Even Louis Daguerre, considered the official inventor of photography because of the statalization and publication of his invention by the French government in 1837, was indeed a painter but was certainly better known for his “diorama”, a theatrical machine that allowed to change theatre sceneries through the combined use of semi-transparent curtains and the light from windows and candles.

Even the first uses of photography were fueled by an exquisitely entrepreneurial attitude, and were closely linked to the concept of progress, in its meaning of “discovery” and “exploration of the unexplored”.

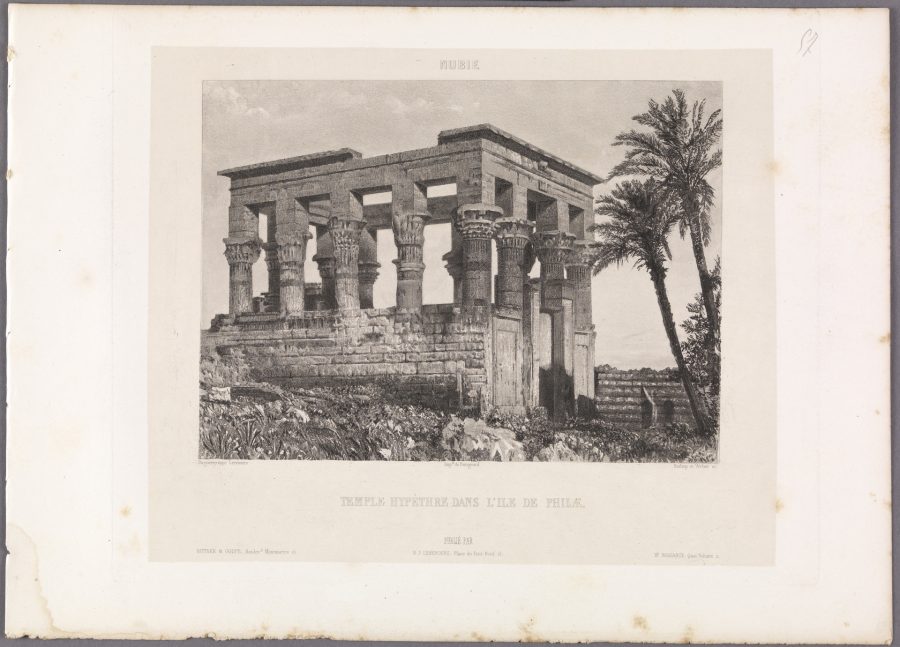

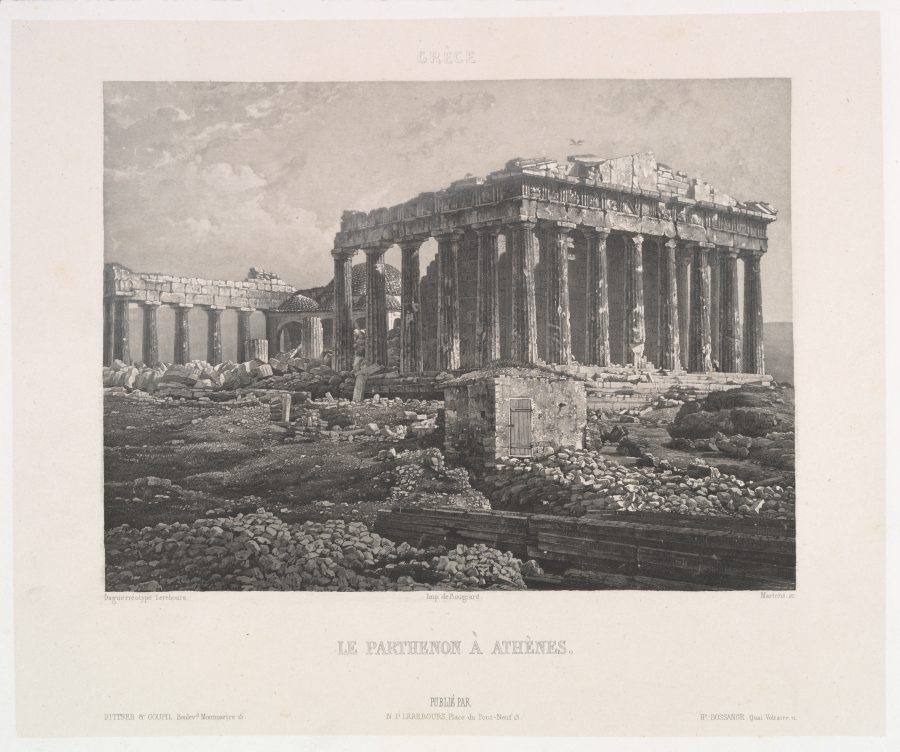

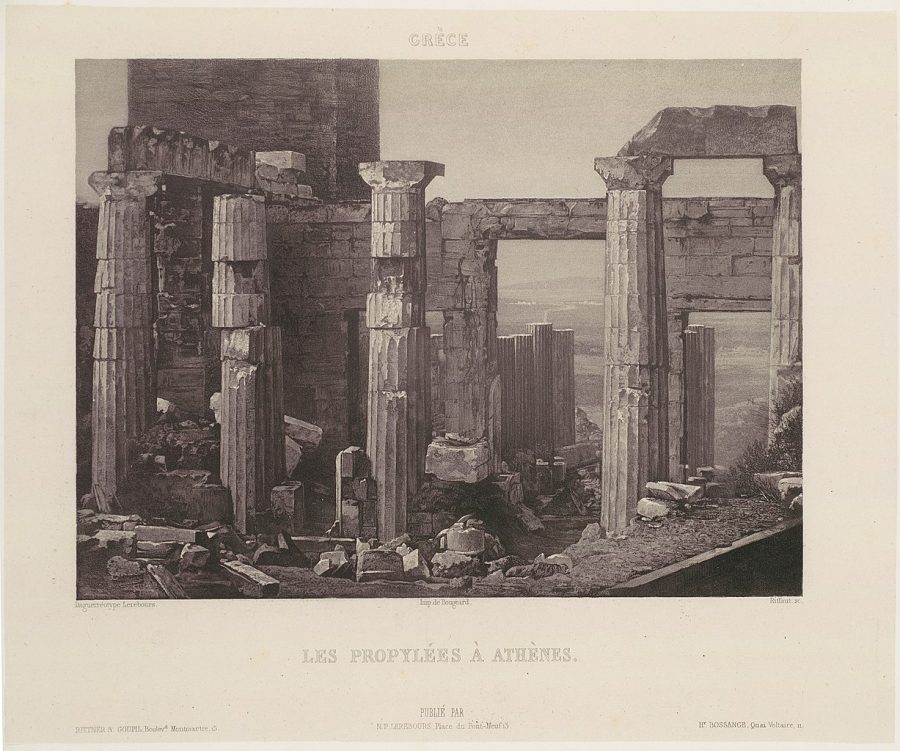

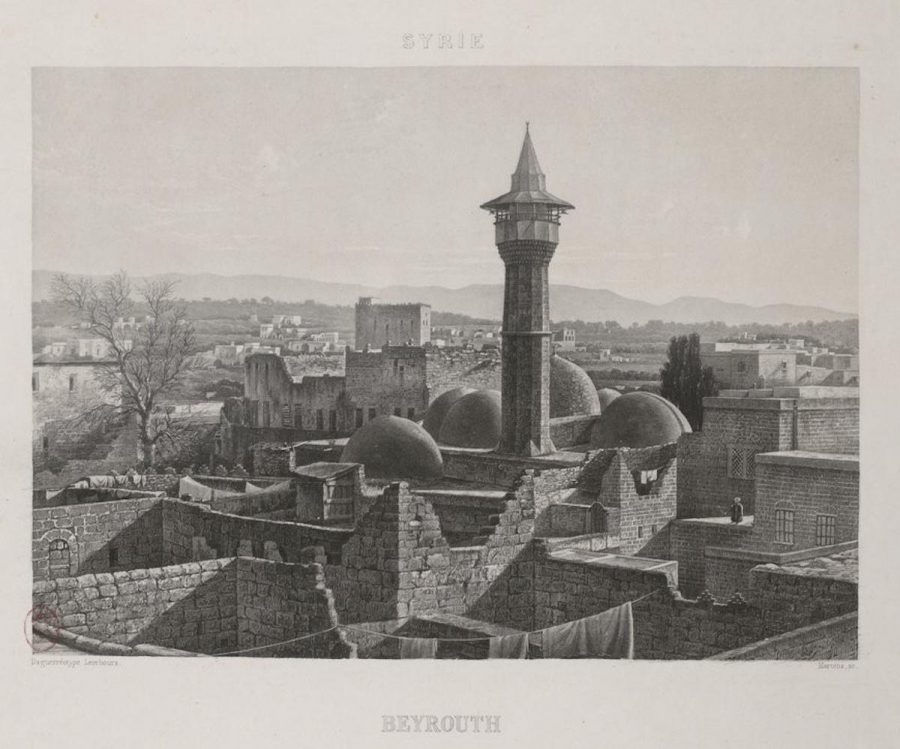

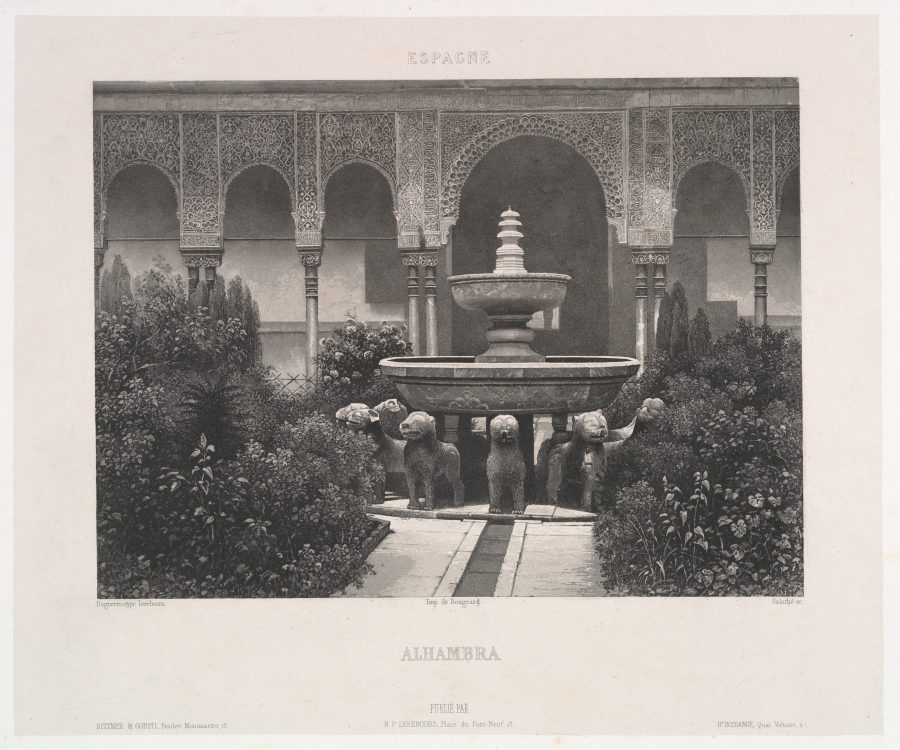

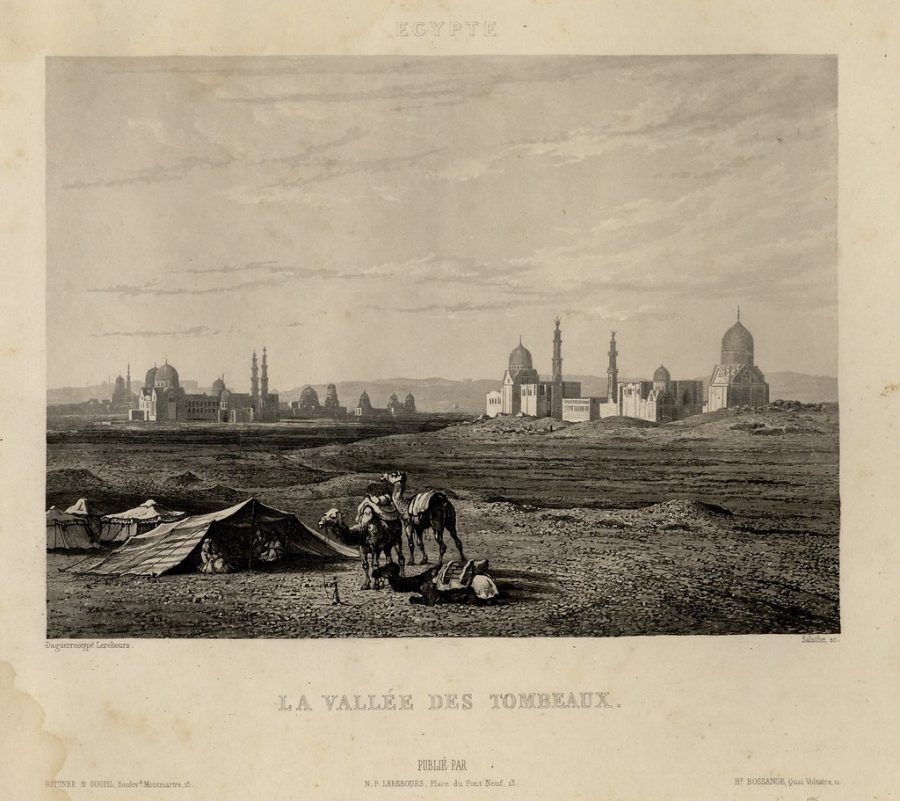

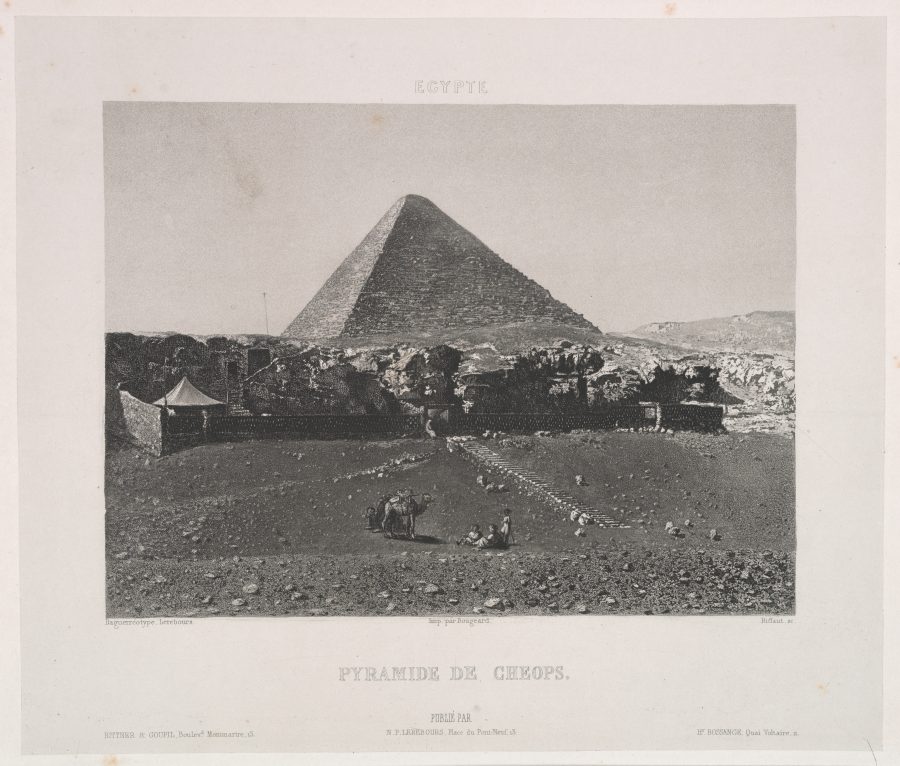

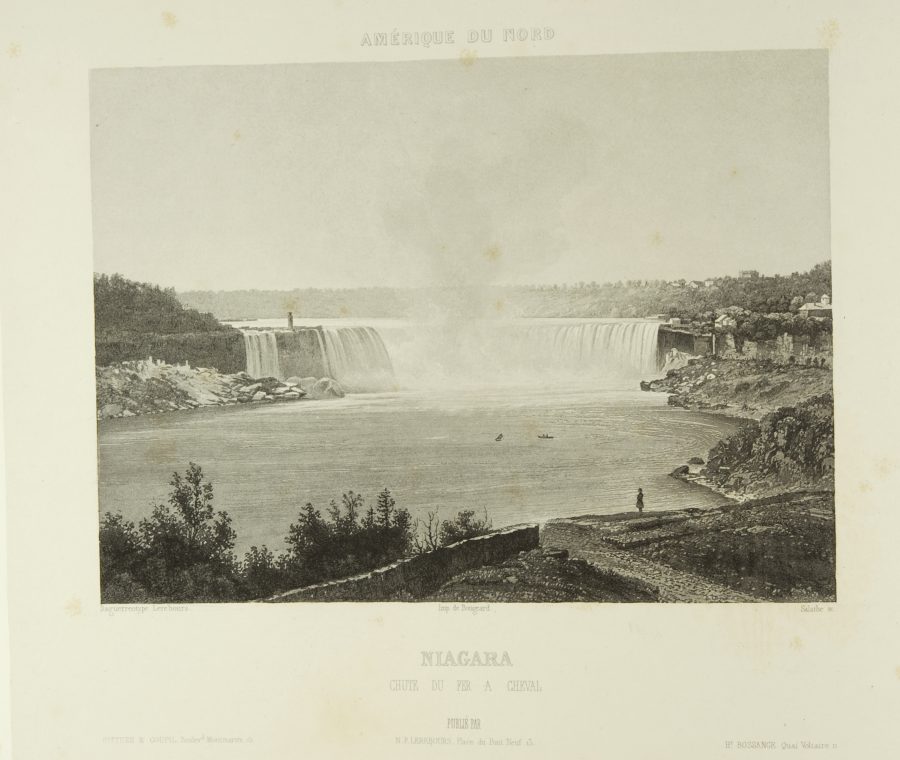

In 1840 (only 3 years after the publication of Daguerre’s findings) the publisher N.M.P. Lerebours produced the Excursions Daguerriennes, a collection of views of landscapes and monuments from Europe, from the Middle East and America which were tremendously successful because they allowed those who could not afford to travel to “see” distant and exotic places for the first time.

The herald of progress

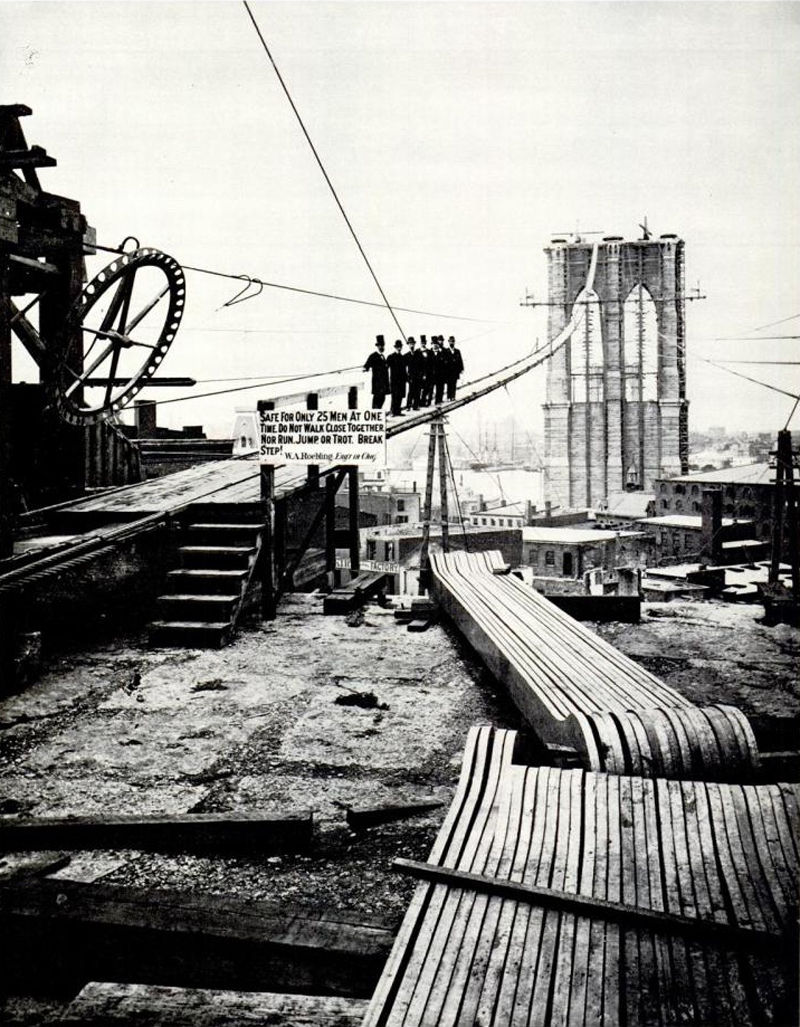

The central role of photography in industrial development was confirmed by the fact that the medium was not only a product of that revolution, but also its greatest propaganda tool: photography sang the enterprises and the discoveries of the new man made in the new world.

John Edwin Mayall

The Crystal Palace at Hyde Park, London, American, 1851

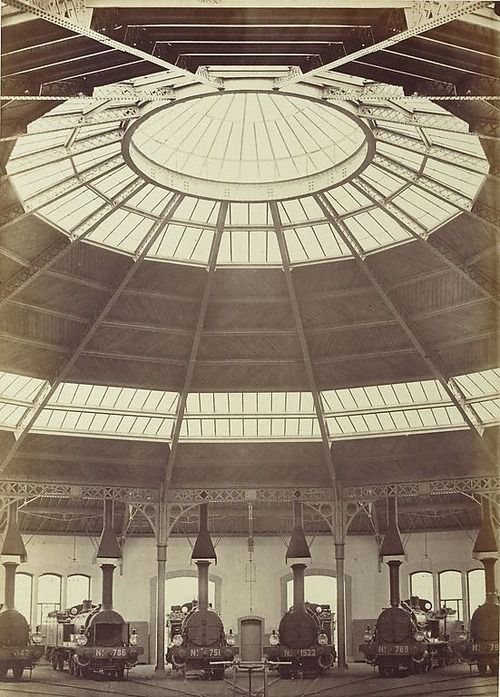

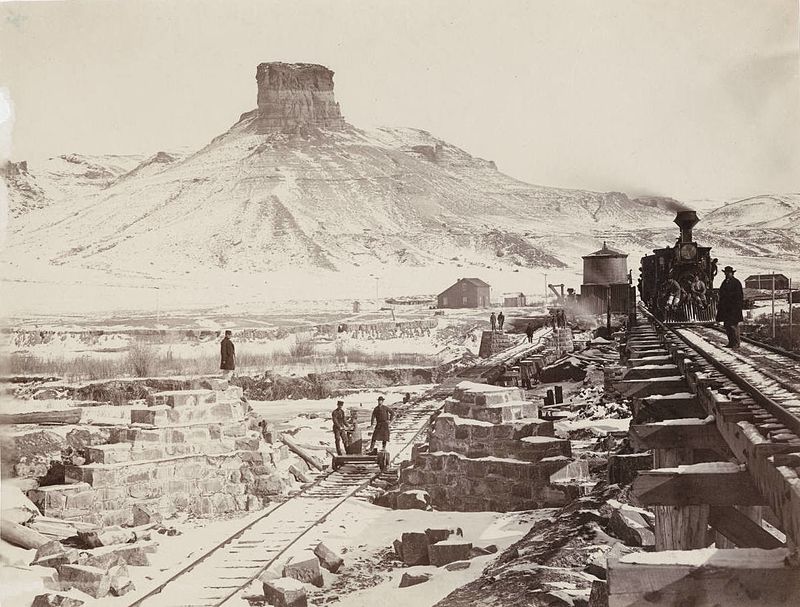

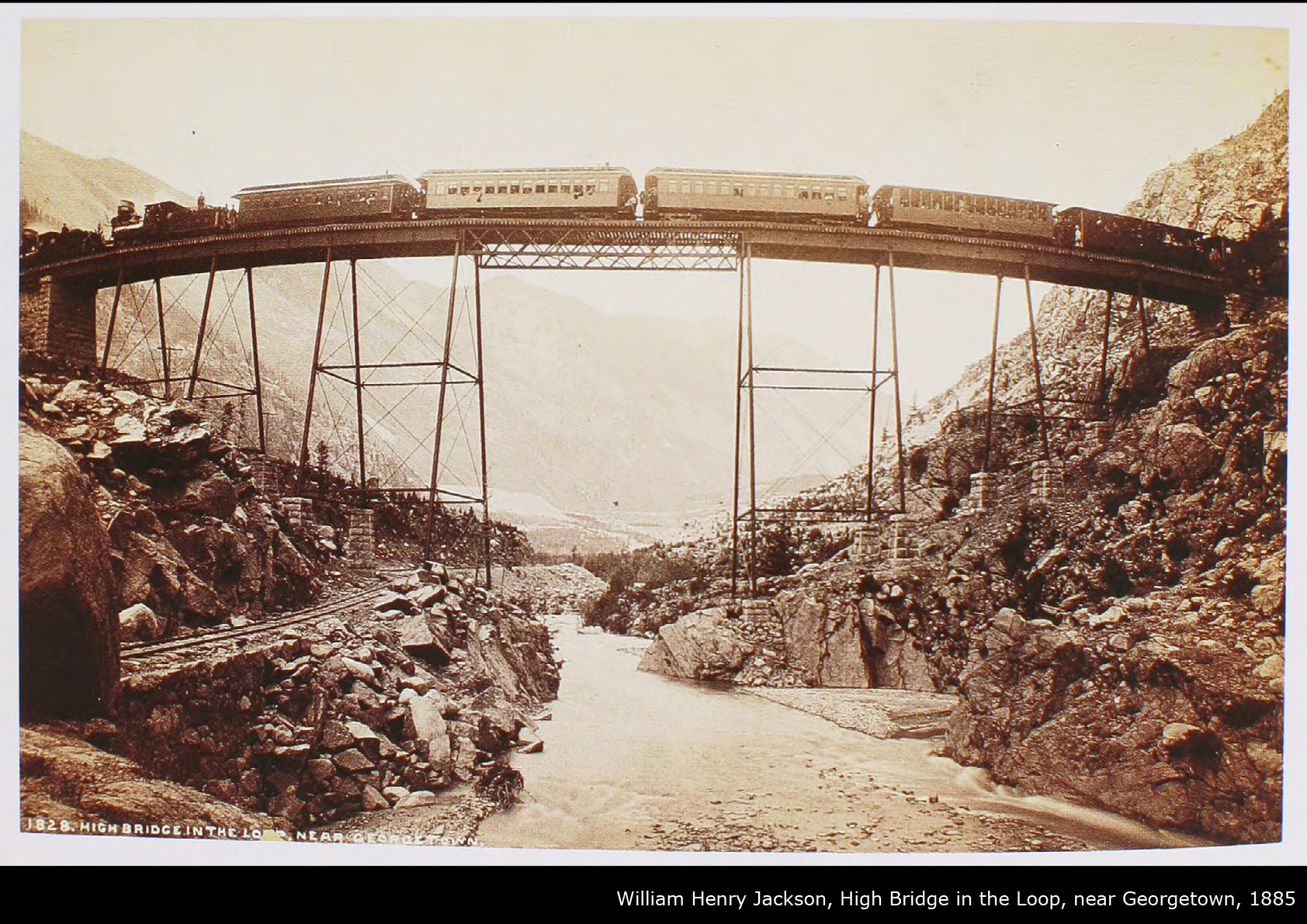

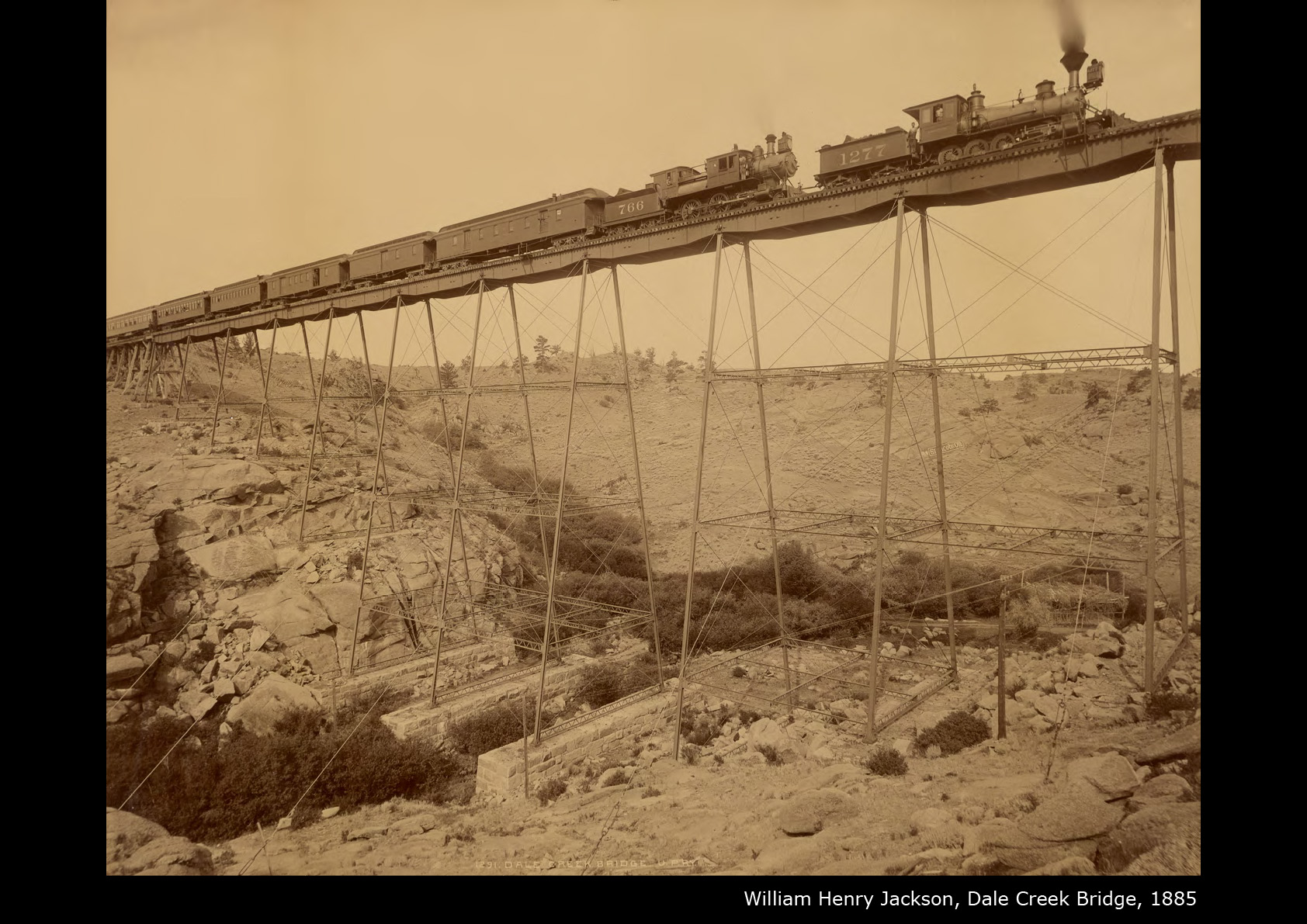

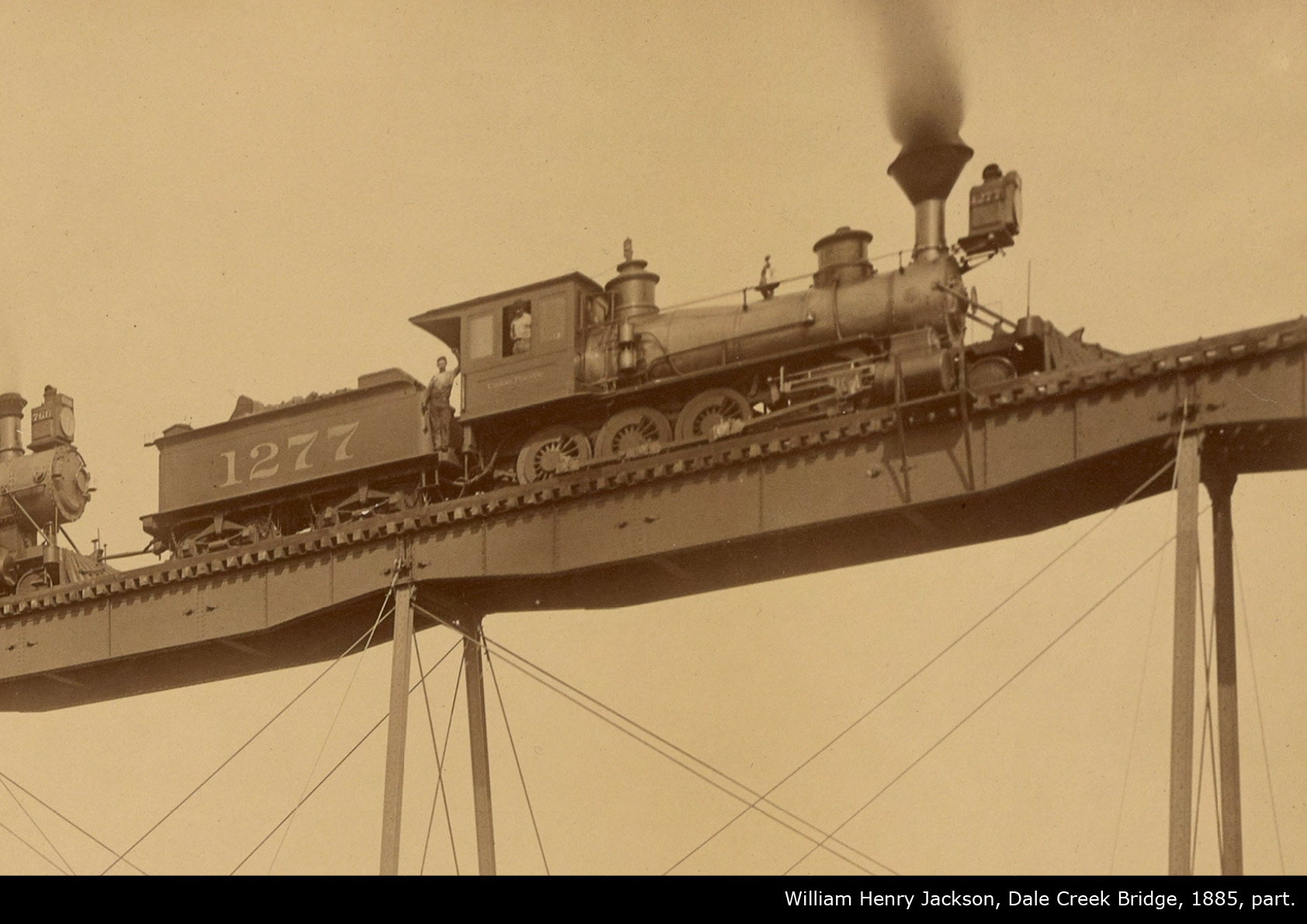

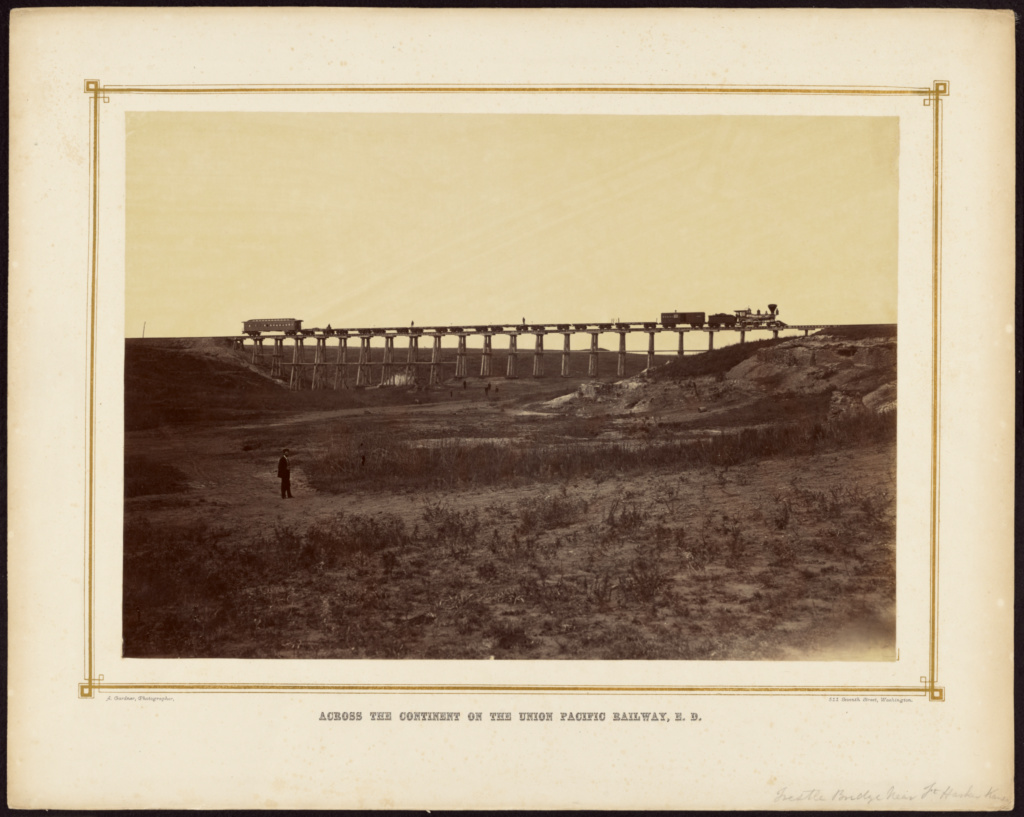

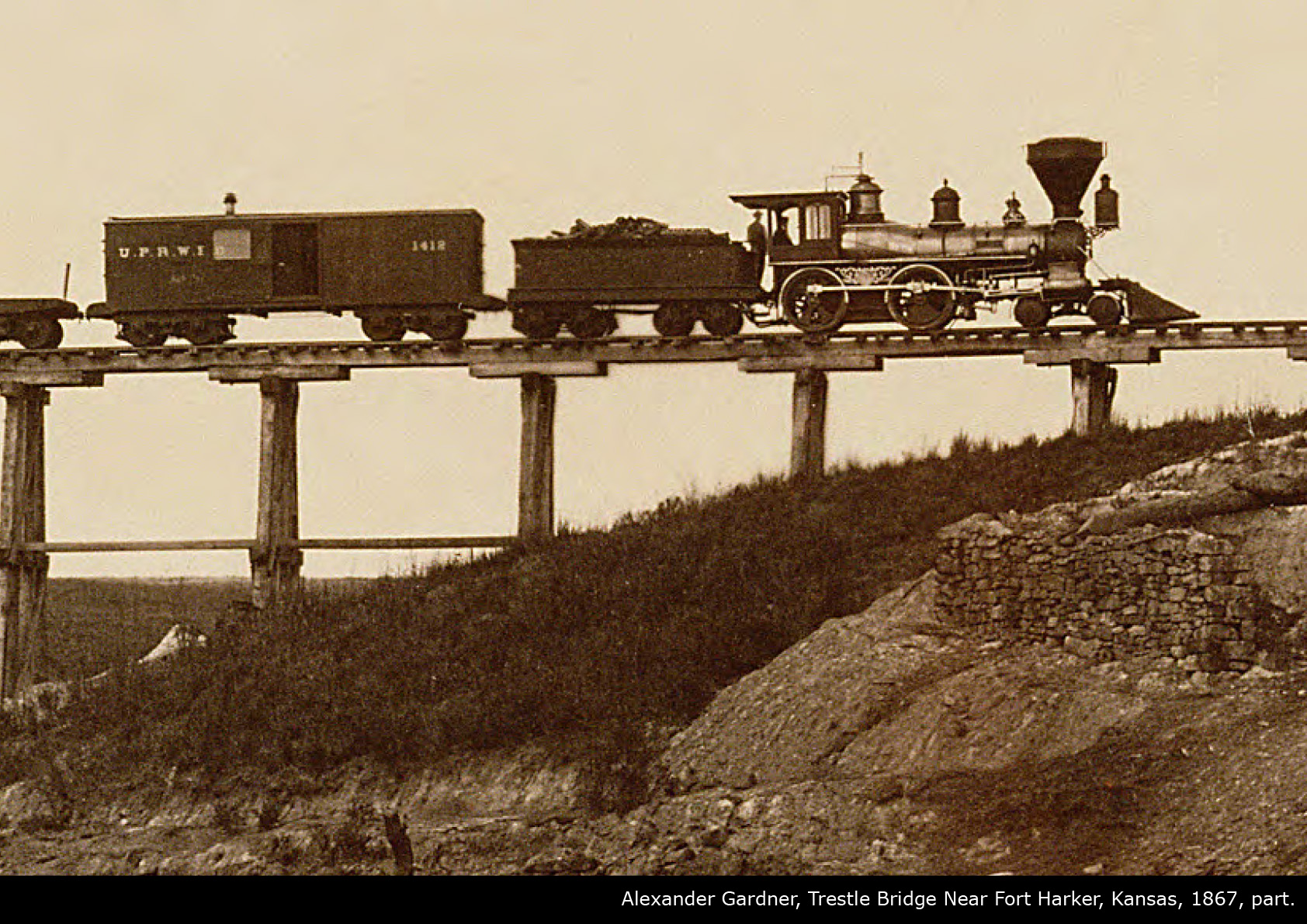

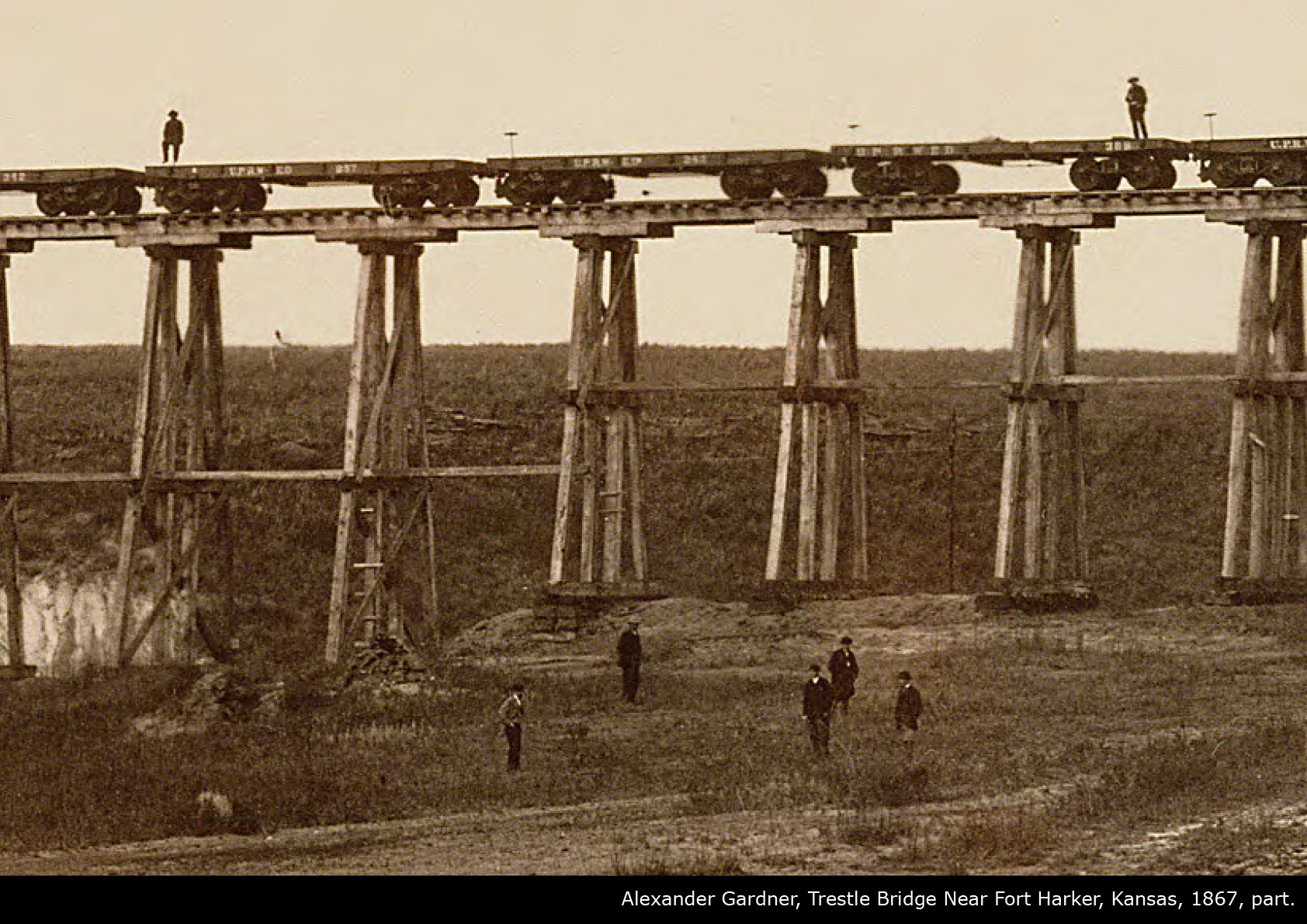

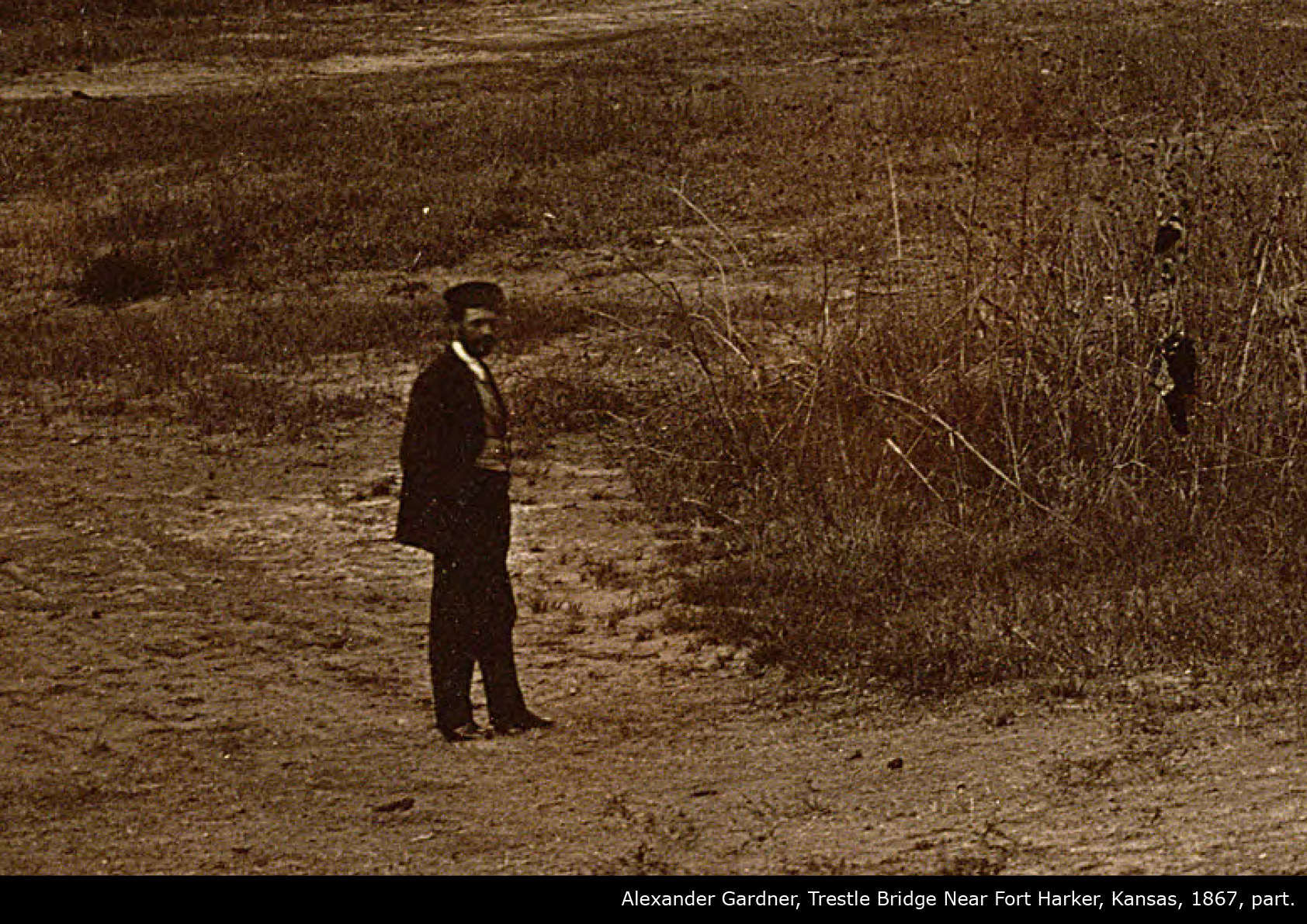

Photography was used to tell the story of another great symbol of human progress: the steam locomotive and the railroad. Together they embodied the myth: working on the construction of the railway and posing for the photographer were two ways to be part of that extraordinary moment in history.

Andrew J. Russell, “East shaking hands with West”, Meeting of the Rails, Promontory Point Utah, 1869

Enlarge: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/aa/East_west_shaking_hands_by_russell.jpg

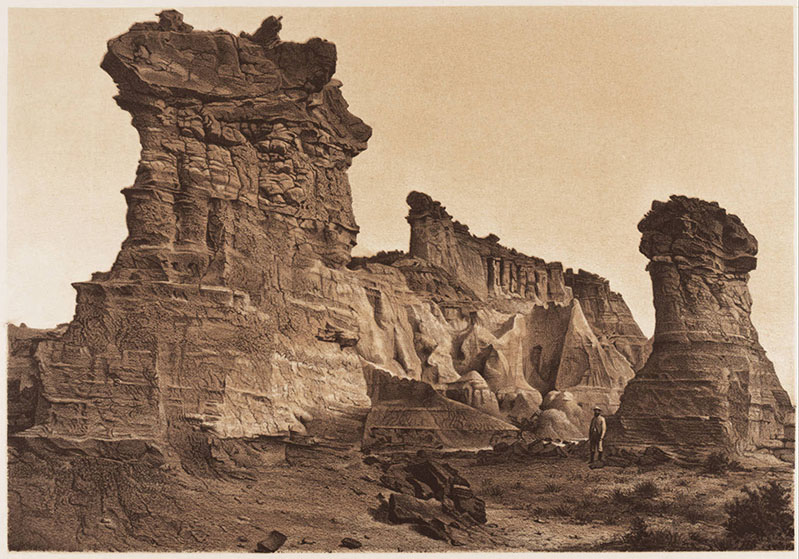

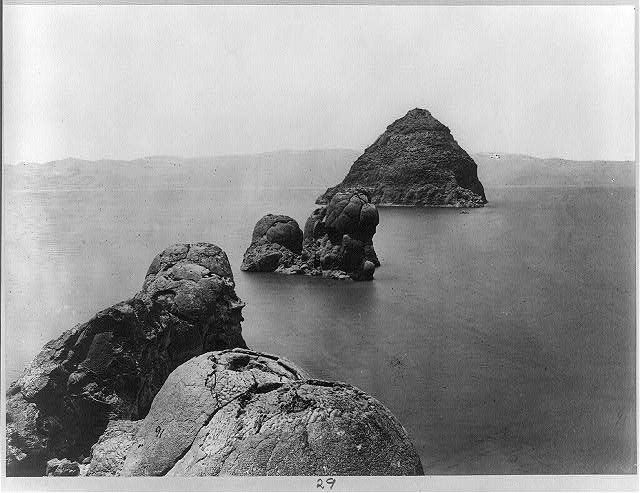

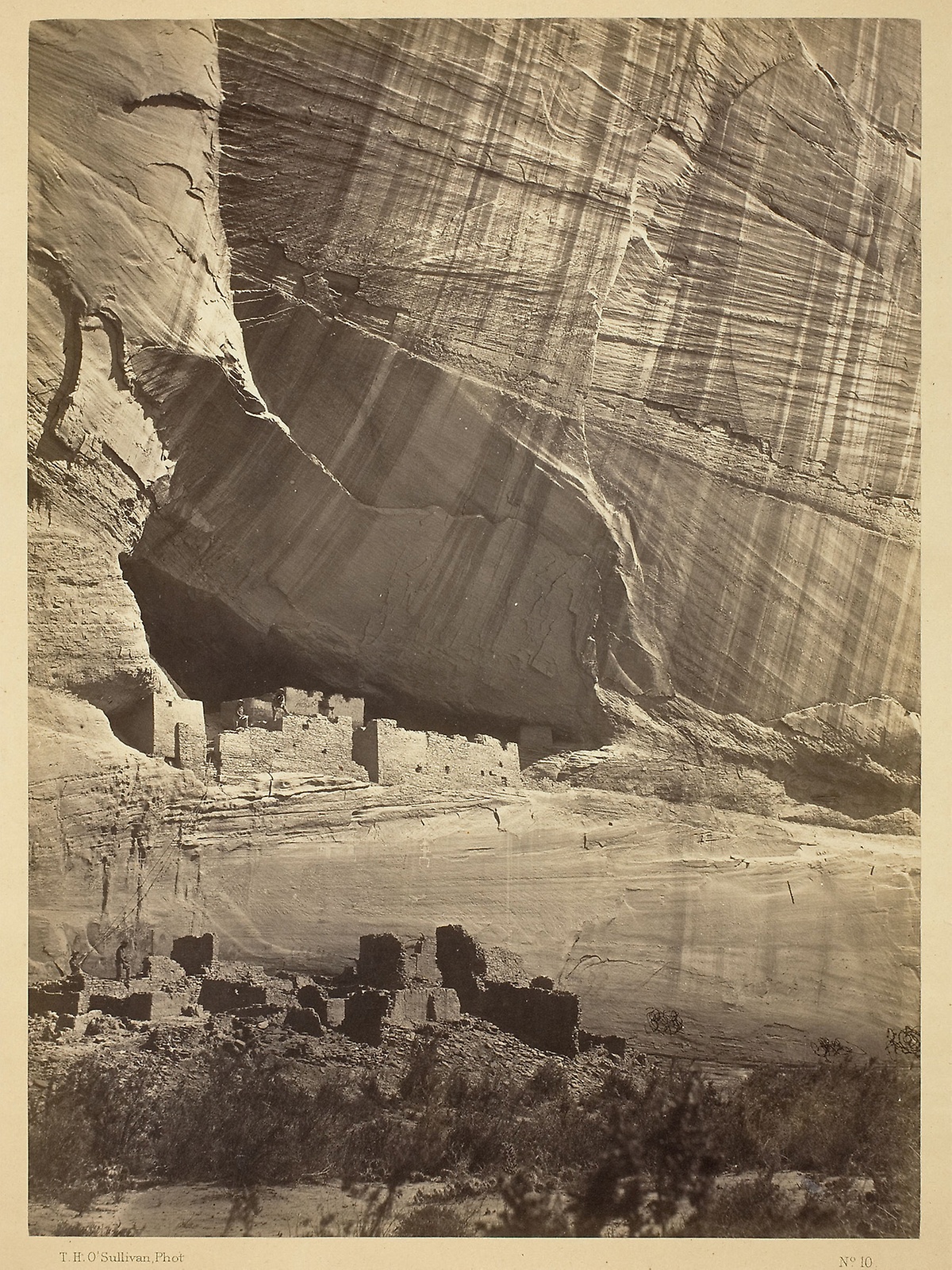

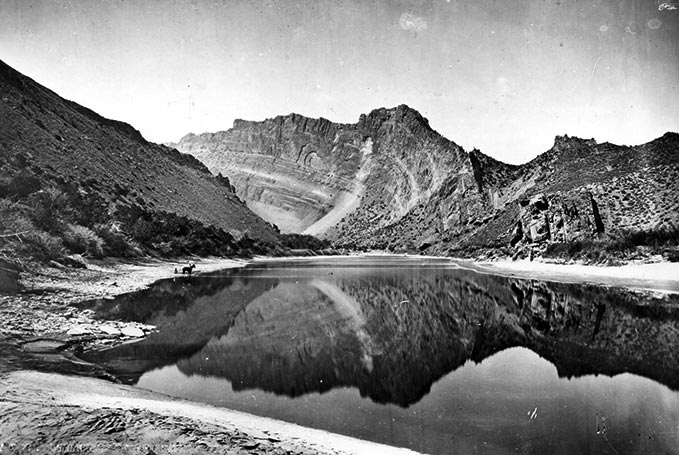

Photography was used as a proof of the exploration of the American West: a group of photographers was engaged in exploratory campaigns funded by the winners of the American Civil War in order to document the beauty and possibilities of the newborn state.

Those photographs, printed in New York and other fast-growing American economic cities, showed entrepreneurs and investors the land and resources in which they could invest to continue the venture.

Clarence King Expeditions at the 40° parallel

George Wheeler Expedition, west of the 100° meridian

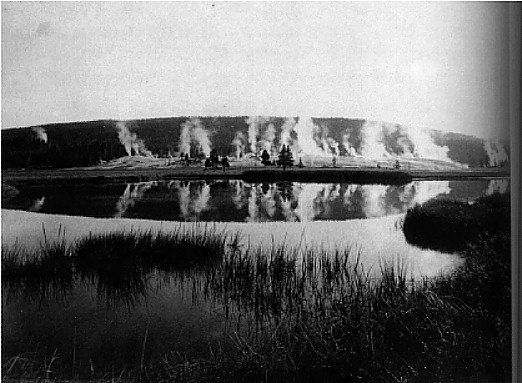

The Beehive group of geysers, Yellowstone Park, 1872. Hayden Geological and Geographical expedition

Summit of Yupiter Terraces, 1871.

Hayden Geological and Geographical expedition

Rocky Mountains

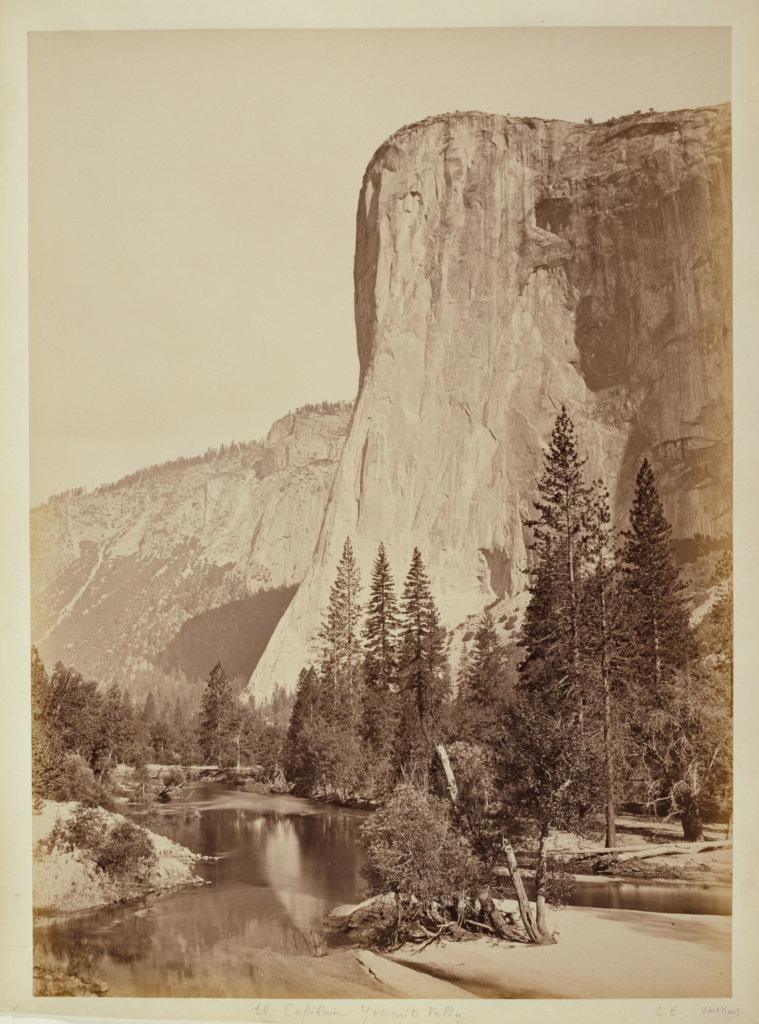

El Capitan, Yosemite, 1865

Yosemite, 1865

Carleton Watkins, Yosemite Valley, California, ca.1865

Carleton Watkins, Yosemite Valley, California, ca.1865

the climax of modern world

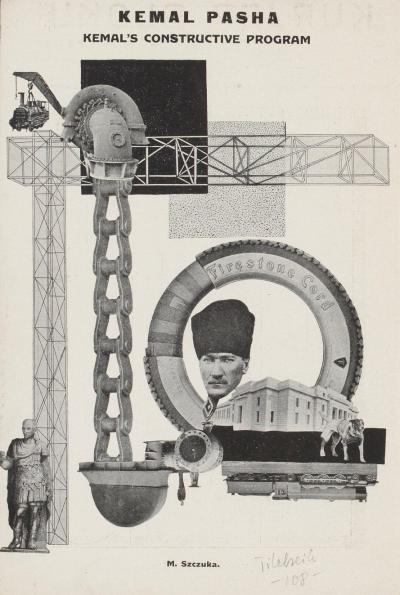

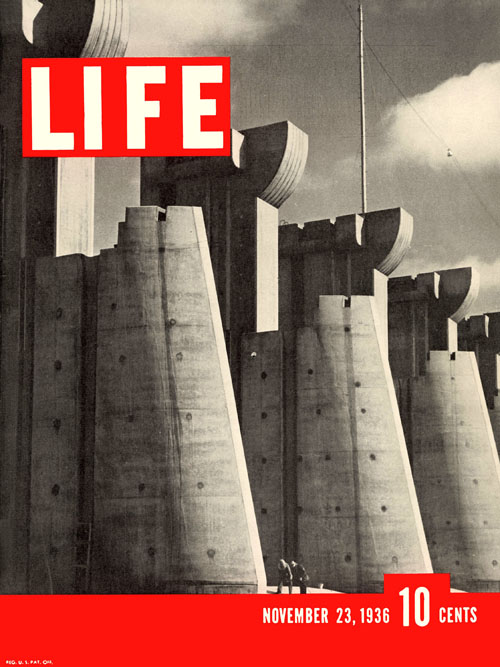

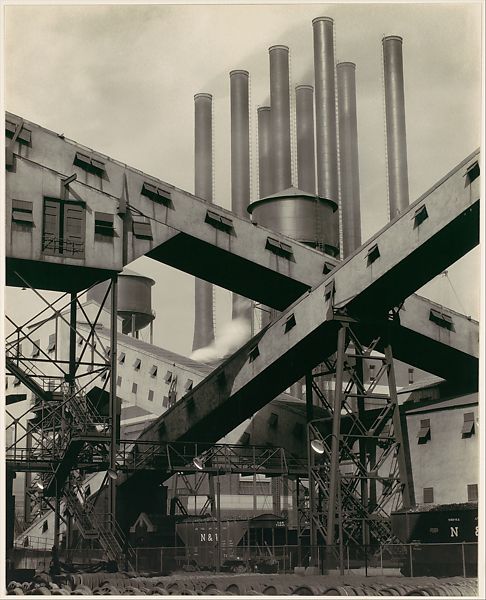

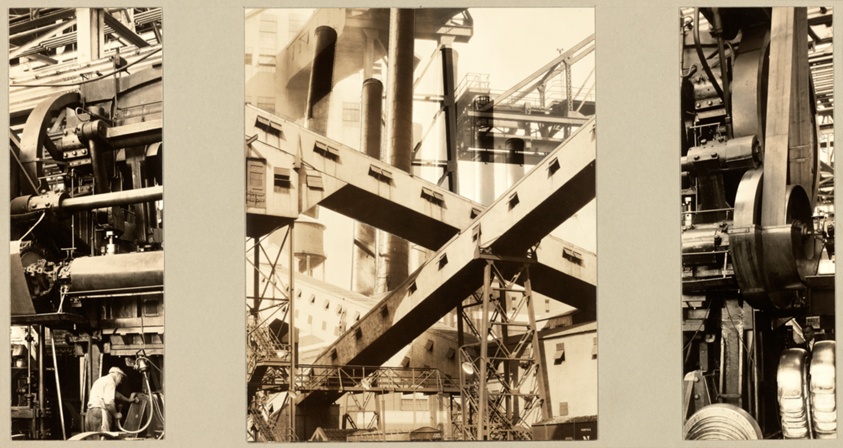

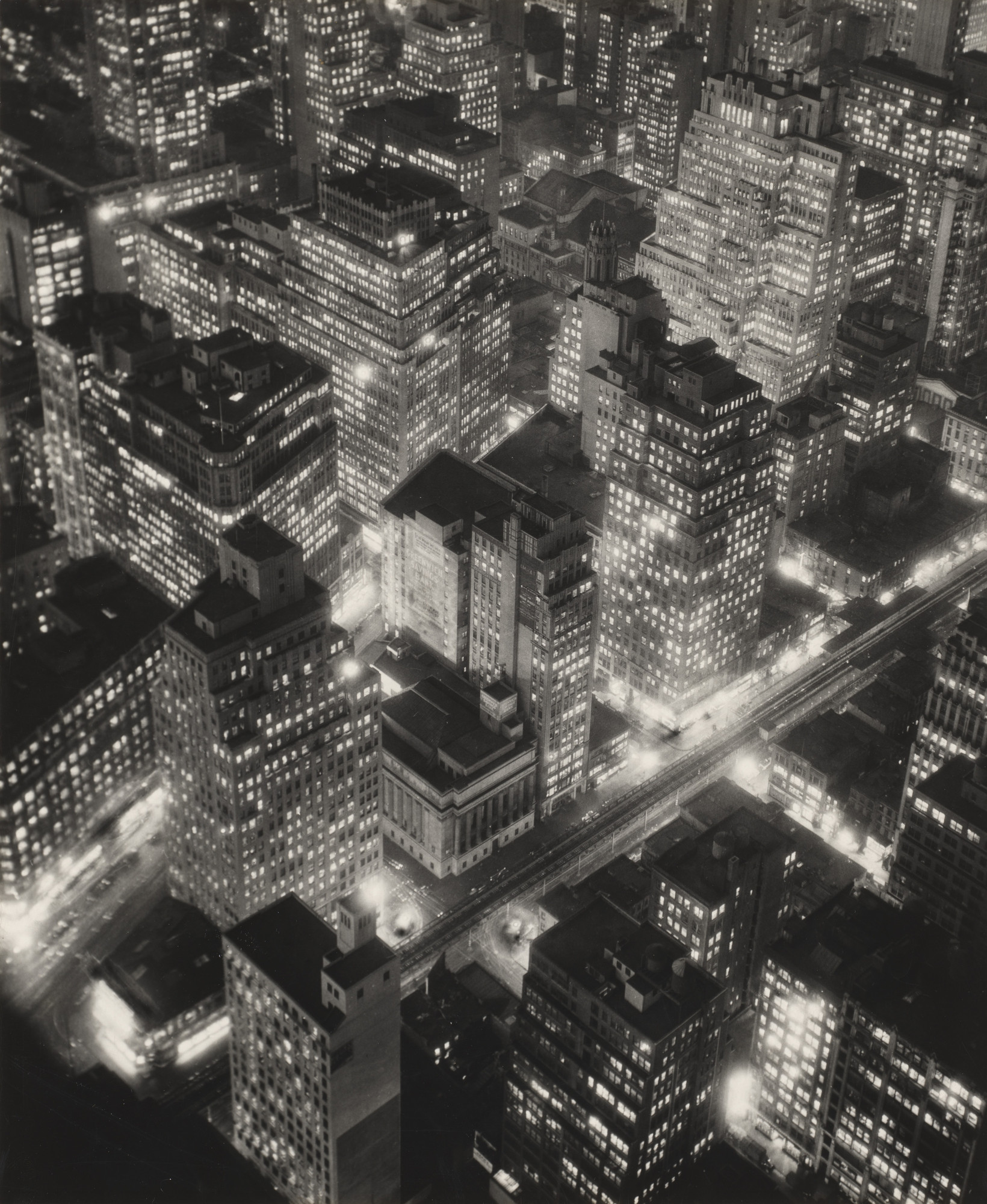

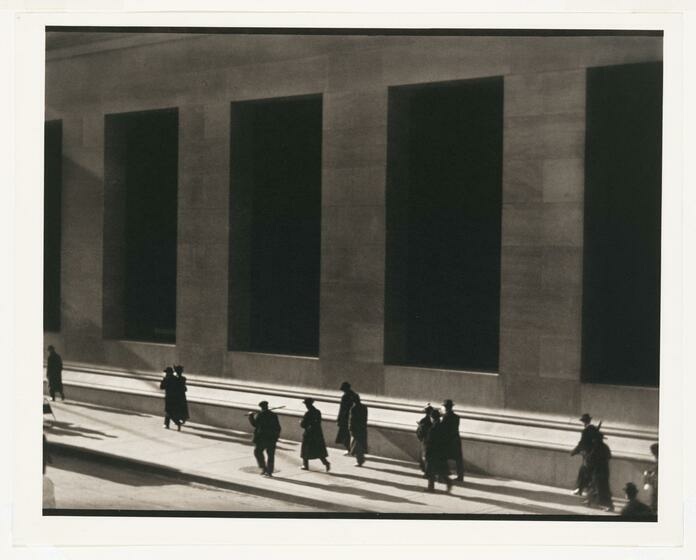

The celebratory attitude towards industrial progress peaks in the first half of the twentieth century and is formalized in an accentuated representation of verticality, speed and progress that will be synthesized by modernist thought and by artistic and cultural movements such as Russian constructivism and American industrialism.

They celebrates an industrial ethos that the artists of the time often turned into an industrial pathos lingering in a form of reverence towards the machine.

Some photographers started to experiment with cinema and produce films showing grand views of the contemporary city. They were called Urban Symphonies and, without abandoning the celebration of mechanization and movement, start to investigate how photography (and cinema ) were able to monumentalize the representation.

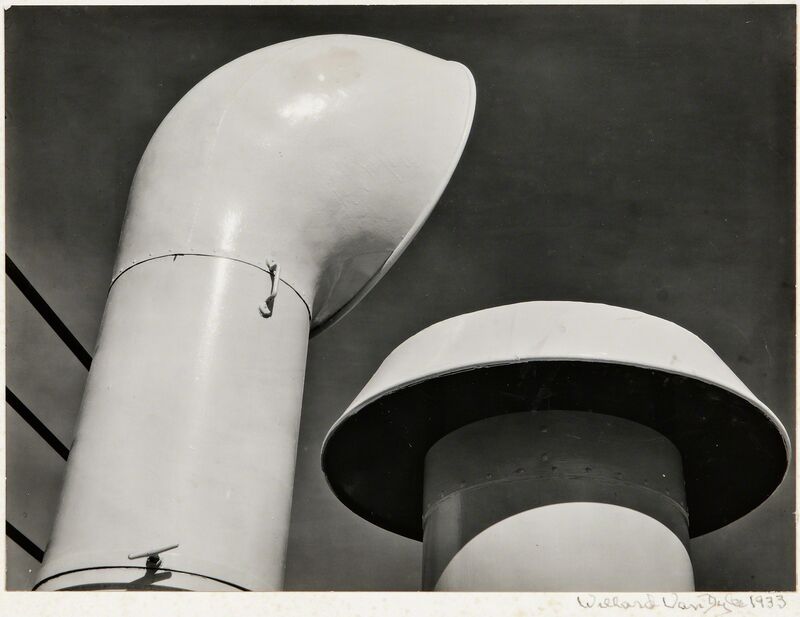

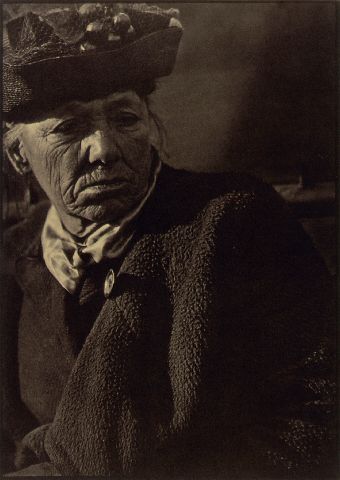

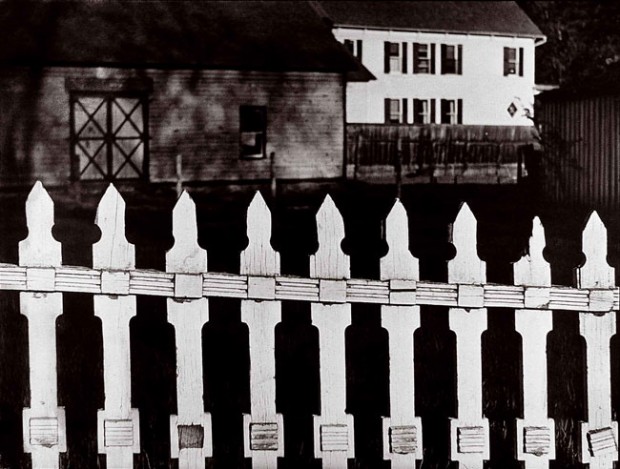

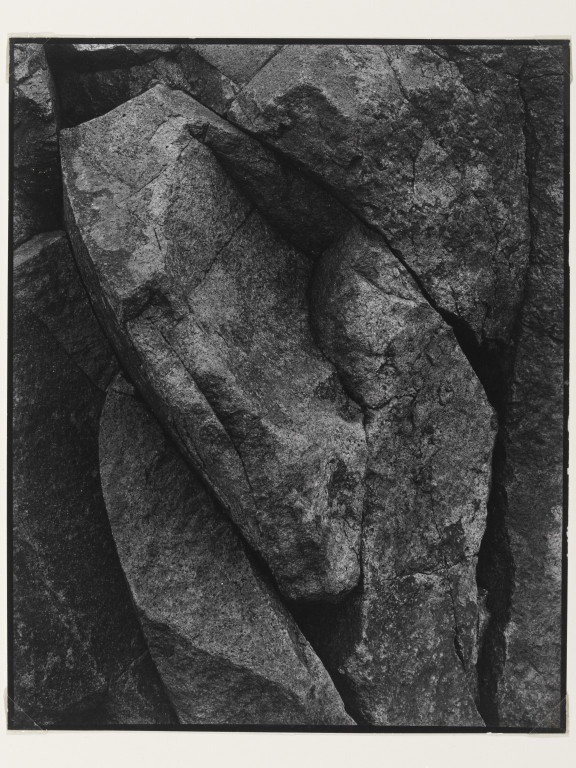

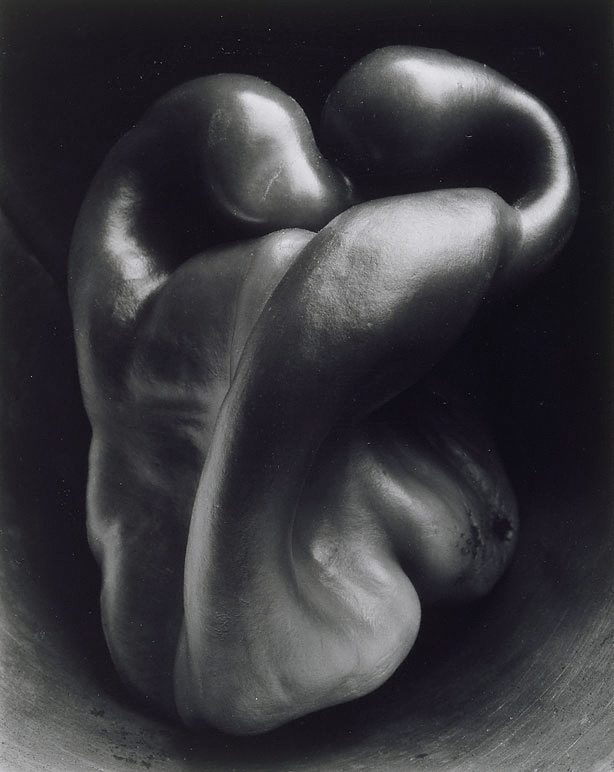

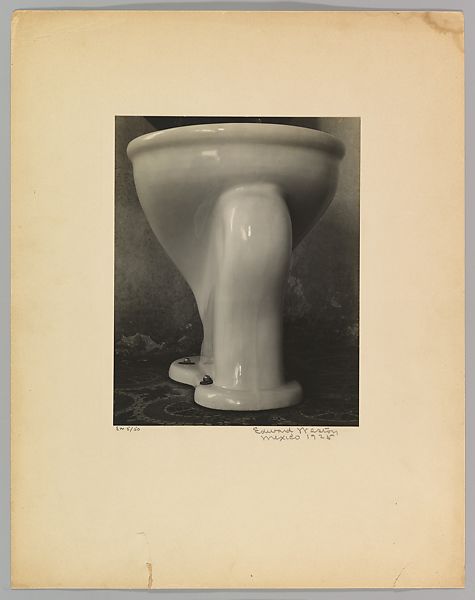

At the beginning of XXth century, along with other artists such as Joseph Stieglitz, Edward Weston or Walker Evans, Paul Strand was proposing a “straight” photography and showing how the medium was able to produce art even by choosing everyday subjects. Those artist were reacting to the pictorial approach of the second half of XIXth century during which many photographer were using methods and chemicals in order to make their photos look like paintings and be considered as art.

In Paul Strand (and the other “straight” photographers) work there is no need for tricks and embellishment and that is a precise statement: the act of framing through photography triggers a process of formalization, aestethicization, monumentalization of its subjects.

“Excusado” shows a further statement by those artists: not only everyday object, but also the most ordinary or even the most despised objects may become art or monument, when they are chosen as a subject fo a photographic or artistic practice.

In fact Weston, Strand and Stieglitz knew that their approach was not isolated limited to photography and that an earthquake was shaking art system since a decade.

Ready-made and the monumentalization of ordinary

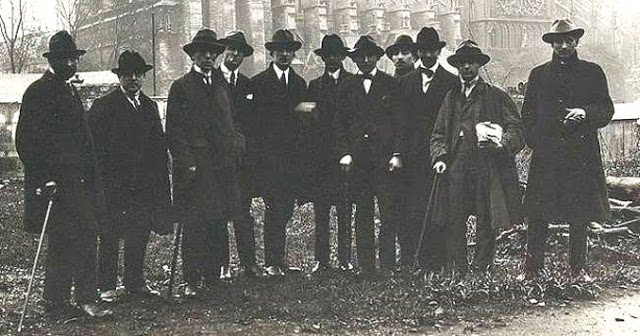

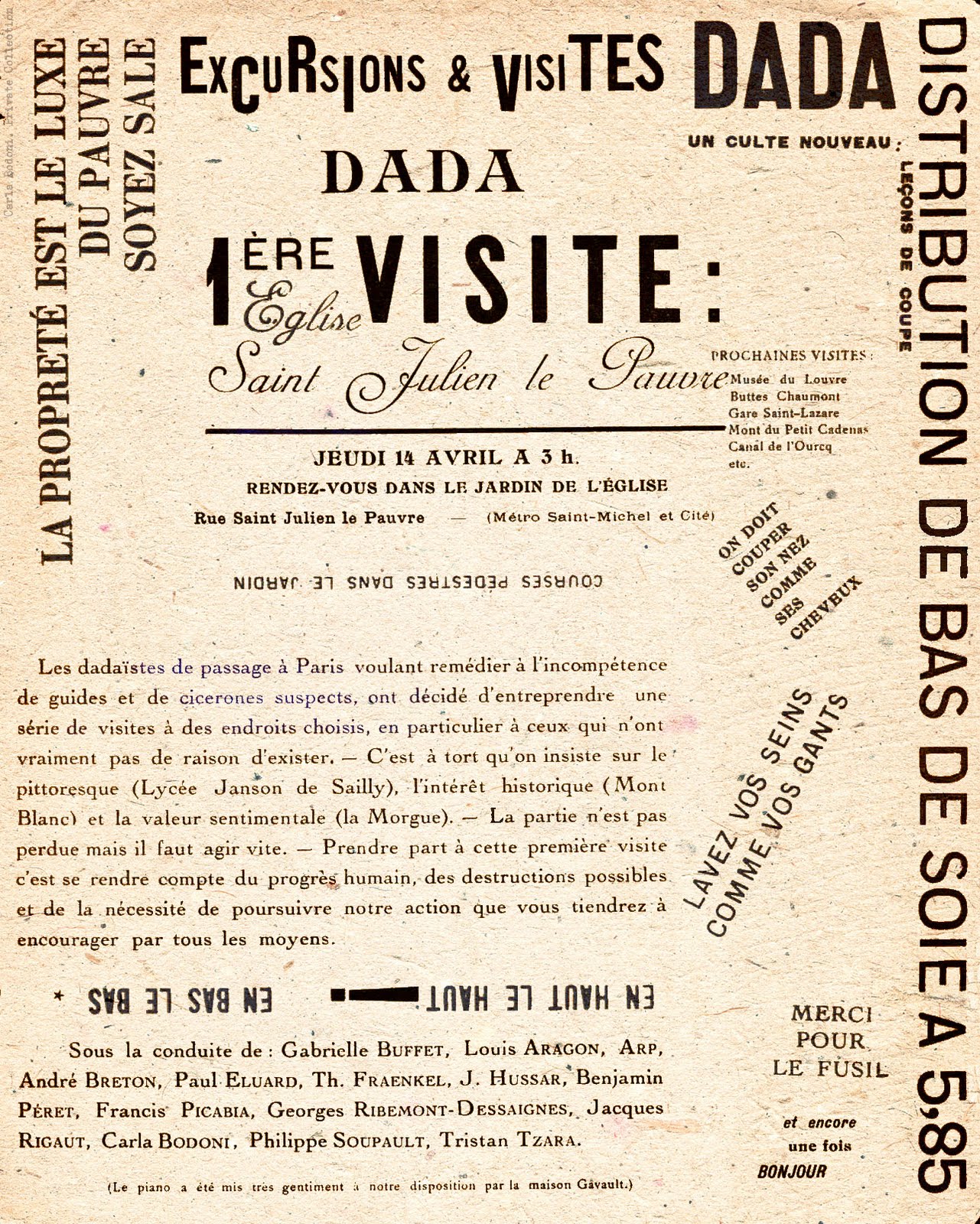

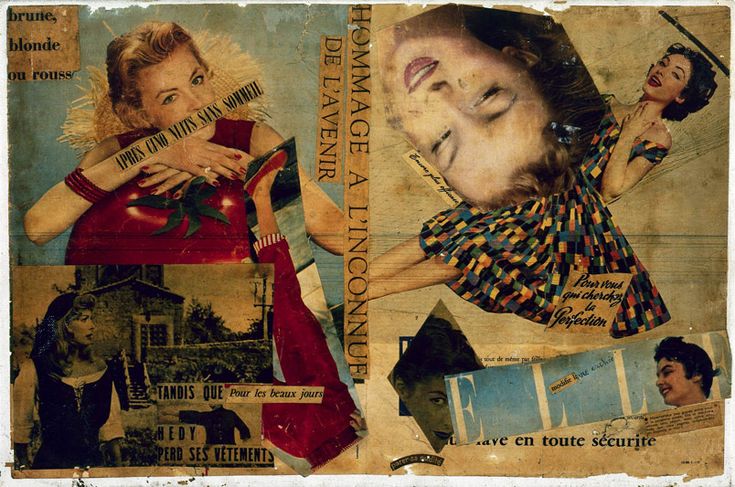

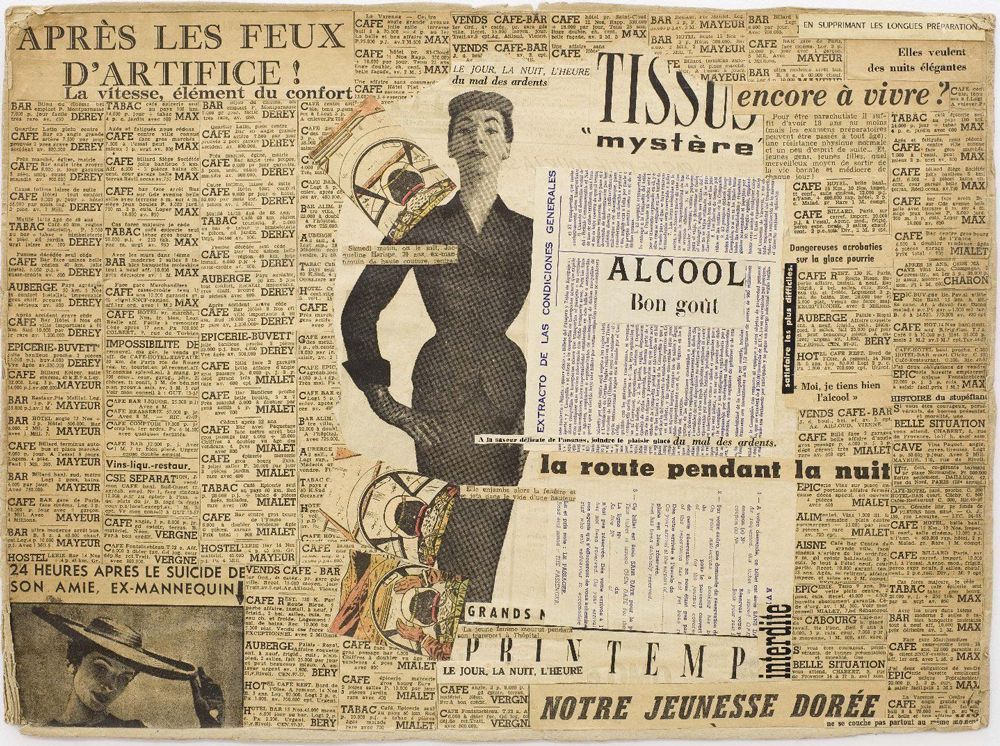

The resemantization caused by the artistic action is taken to dogma by Dada, Surrealists and Situationist artists and is applied to different artistic practices: from sculpture to architectural design, from the construction of images and texts to the reappropriation of the territory and the landscape through exploration and walk.

Dadaist “visite”, the surrealist “merveilleux quotidien” or situationist “derive” have in common the moral reconfiguration of the ordinary, the banal or the marginalized through art.

The emergence of the banal and the everyday ethos coincides with the abandonment of the grand narrative that was typical of modernism.

The term “postmodernity” was first used as a general theory for a historical movement in 1939 by Arnold J. Toynbee: “Our post-modern era was inaugurated by the world war of 1914-1918”.

Some works by land artists from American Minimalism during the 60s are still linked to the dada and surrealists walks in the outskirts of urbanization and further investigate the sublimation of ordinary through art practice.

In 1966 Tony Smith turns New Jersey Turnpike Highway under construction into a work of art by simply giving an account (on Artforum magazine) of a trip by car he did on this highway.

In the now-famous interview, Smith described the drive as a revelation. To his mind, it seemed to challenge the conventional categories of artistic practice and raised questions about the division between art and everyday events. “The road and much of the landscape was artificial,” he said, “and yet it couldn’t be called a work of art. On the other hand, it did something for me that art had never done. At first I didn’t know what it was, but its effect was to liberate me from many of the views I had about art. It seemed that there had been a reality there that had not had any expression in art.” That reality could not be described, Smith said; it was something one had to “experience.”

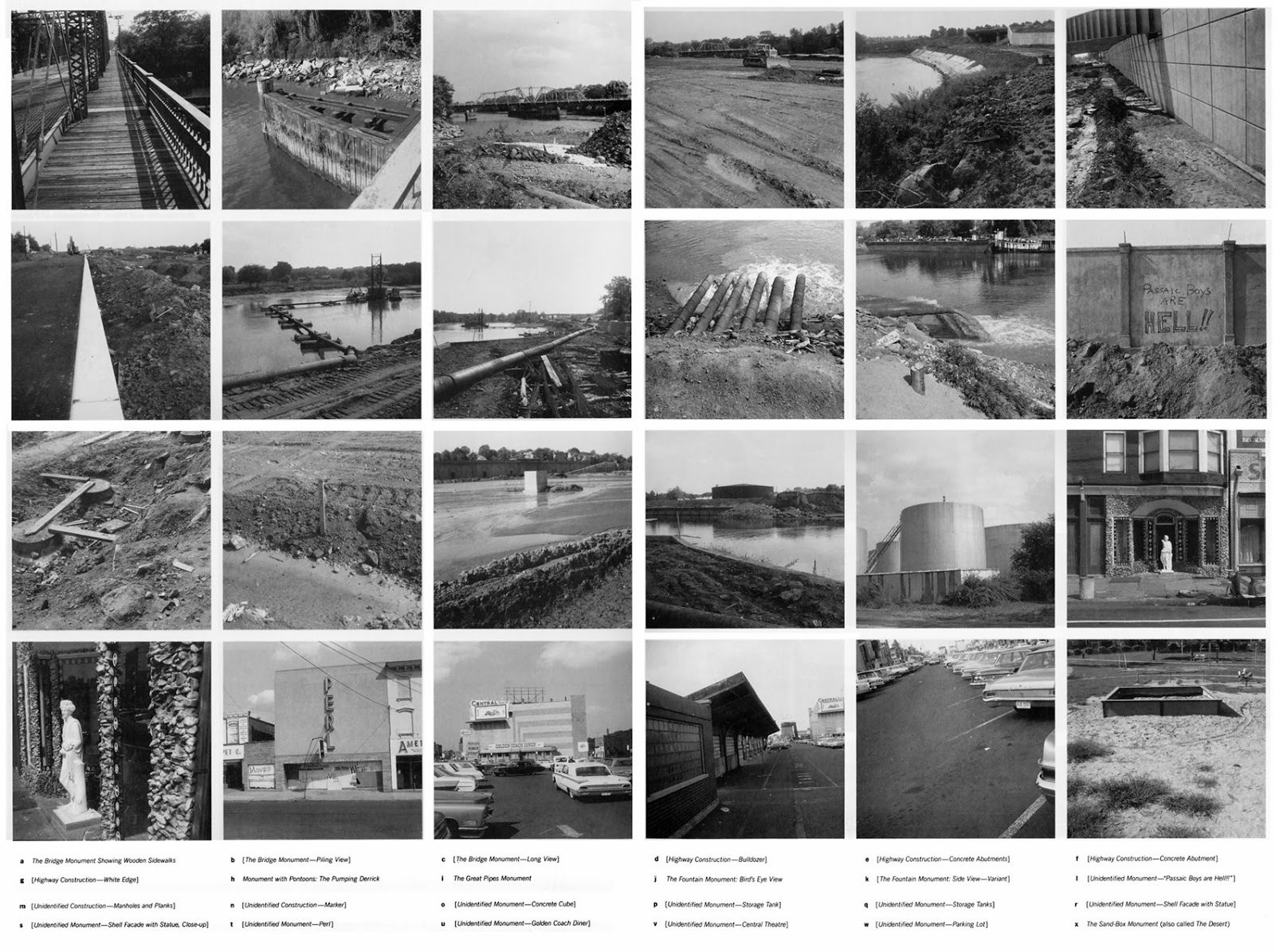

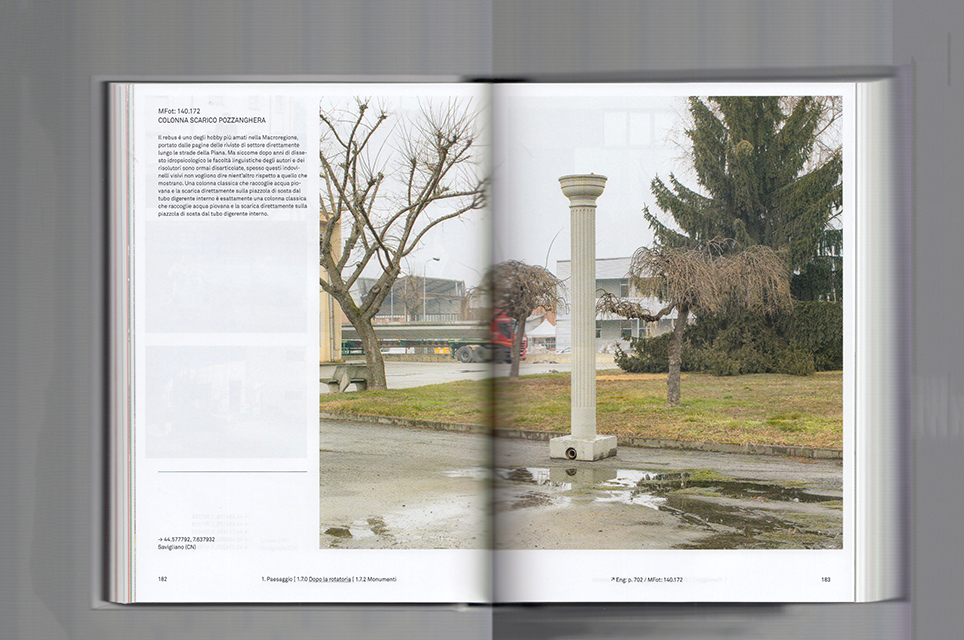

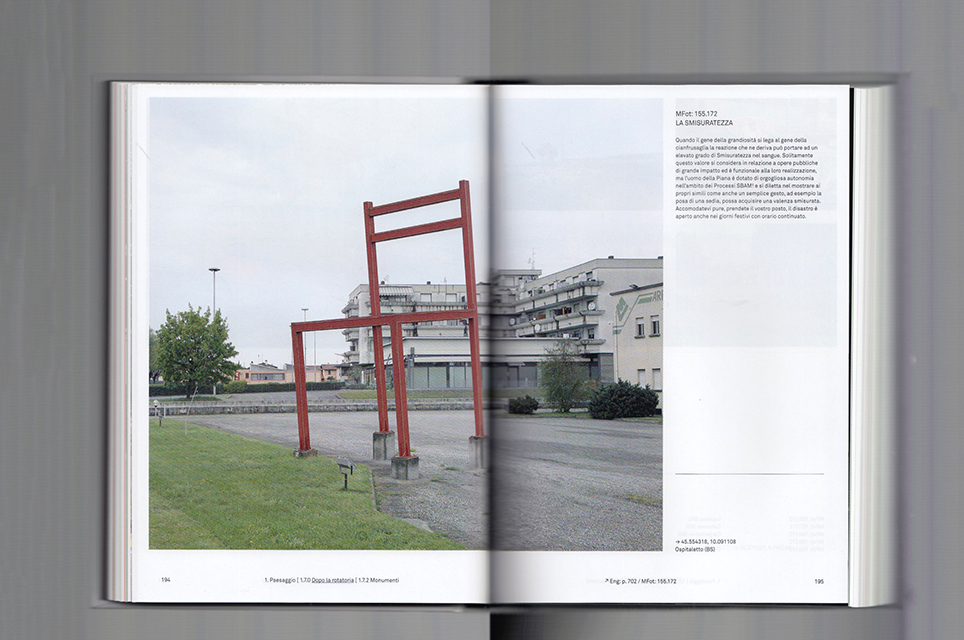

In 1967 Roberth Smithson made a trip between New York and the village of Passaic in New Jersey, where he had grown up, and produced a short textual and visual essay in which he describes the various industrial and suburban relics he encountered during the journey, reconfiguring them into hypothetical monuments of a civilization to come. “A tour of the monuments of Passaic, New Jersey” gives us a very clear example of the reconfiguration that artistic (or photographic) practice produces on how we look at a given landscape.

The explicit use of the term “monuments” reveals the intentions of Smithson. What we now recognize as unfortunate or neglected can be a monument. Even something we feel ashamed of can become part of cultural or artistic heritage.

Photography is not Smithson’s main medium, but he uses the camera to decompose reality into samples and items that he “picks” on film in order to turn them into cultural products along with the landscape they form.

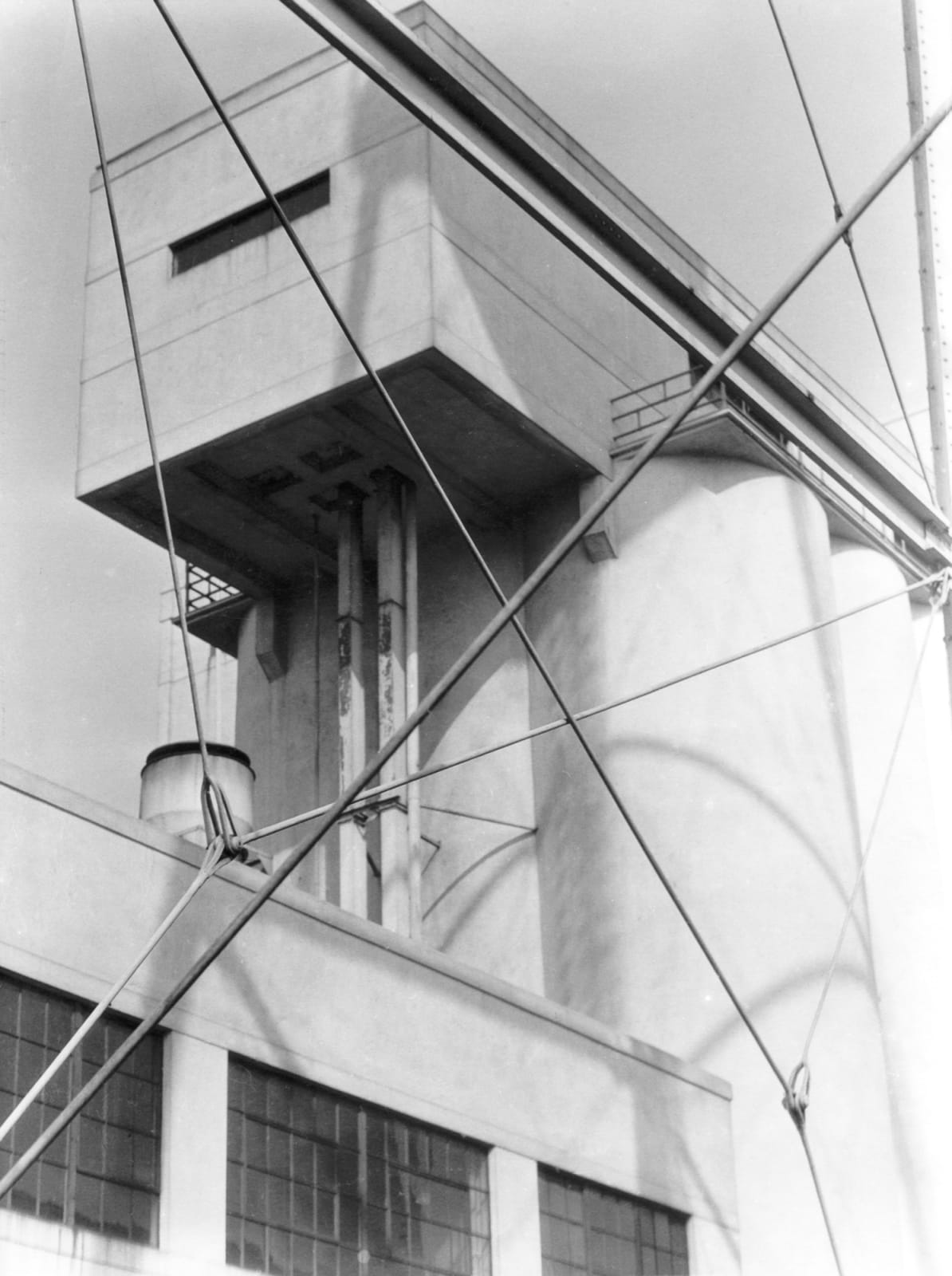

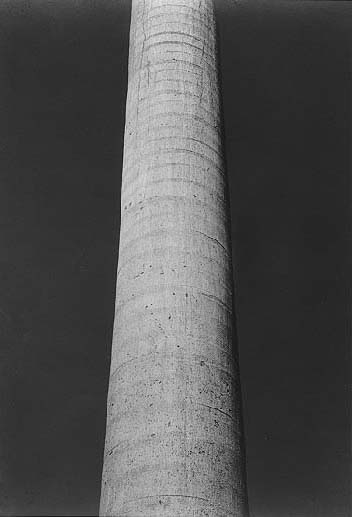

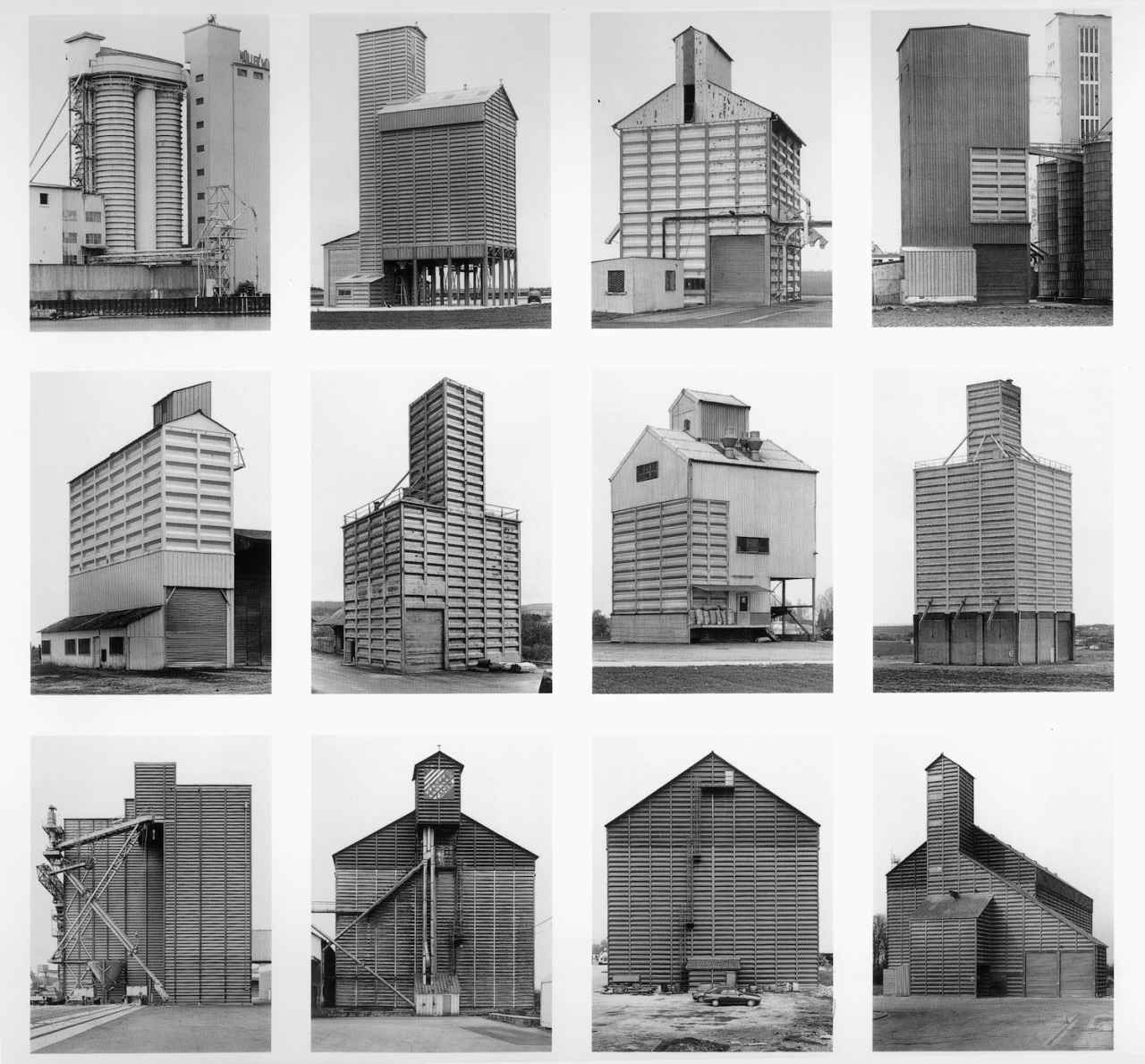

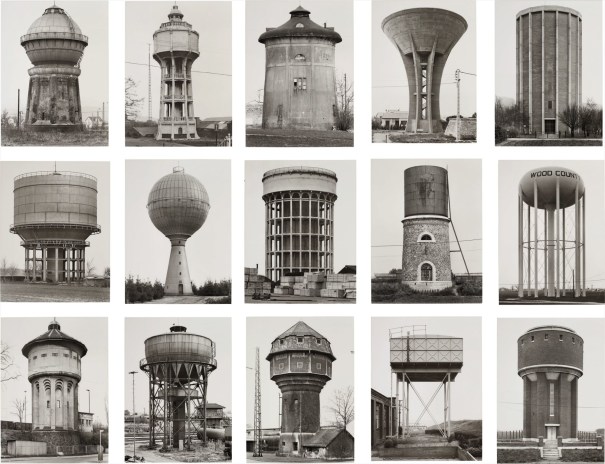

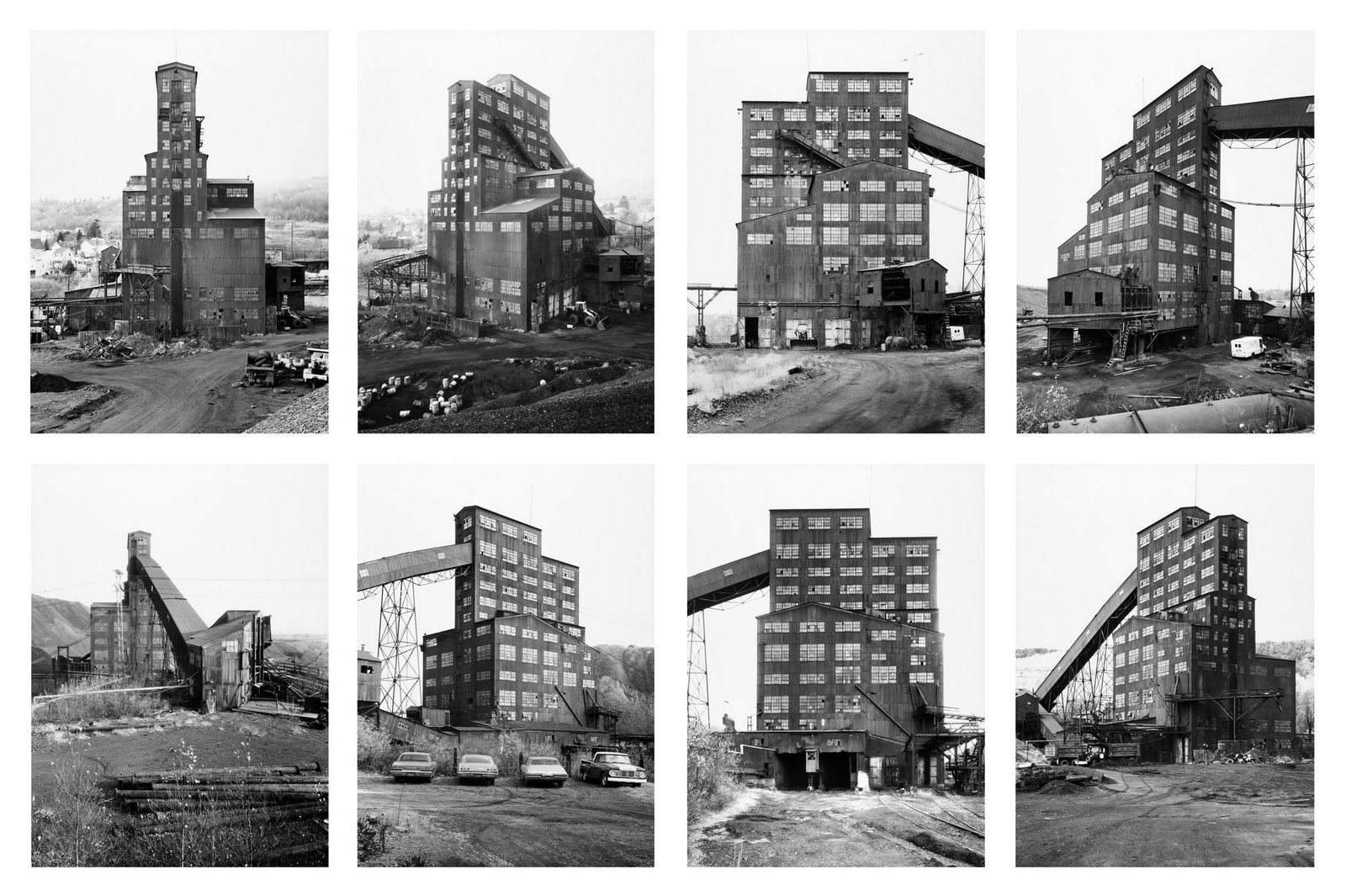

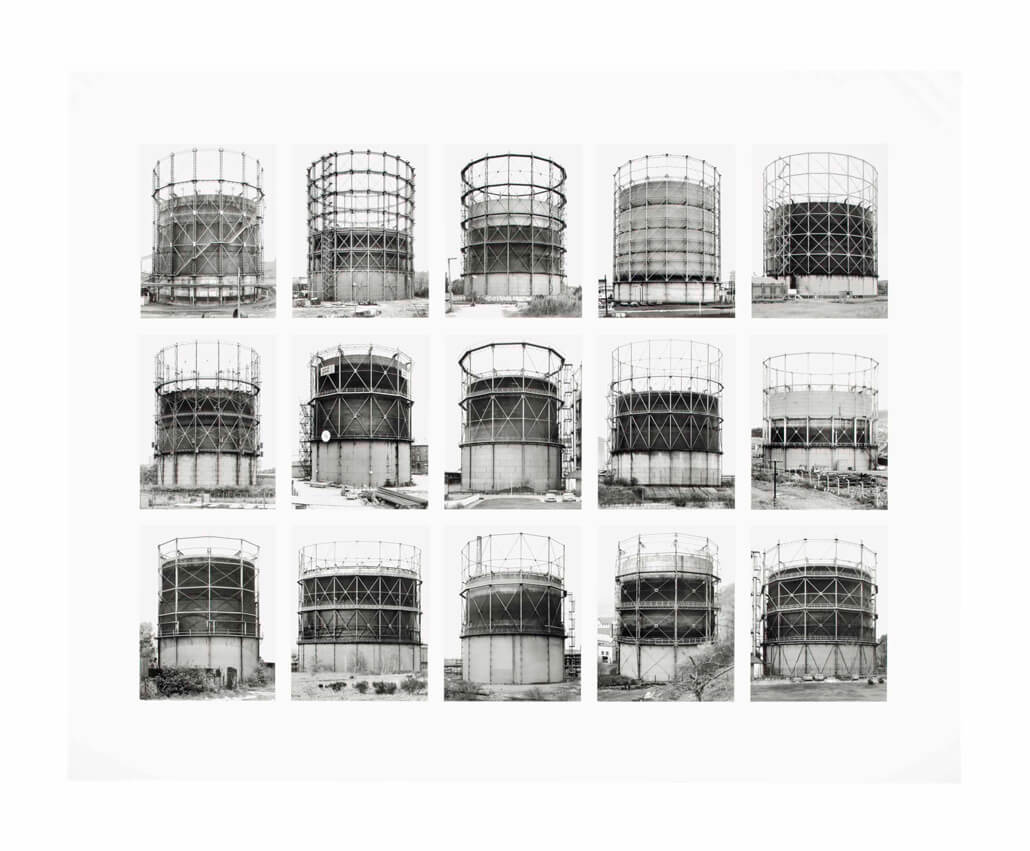

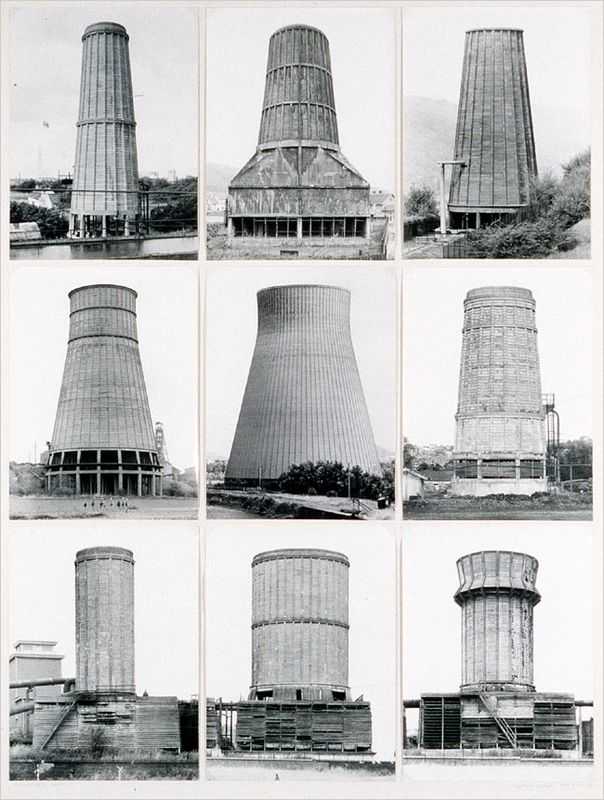

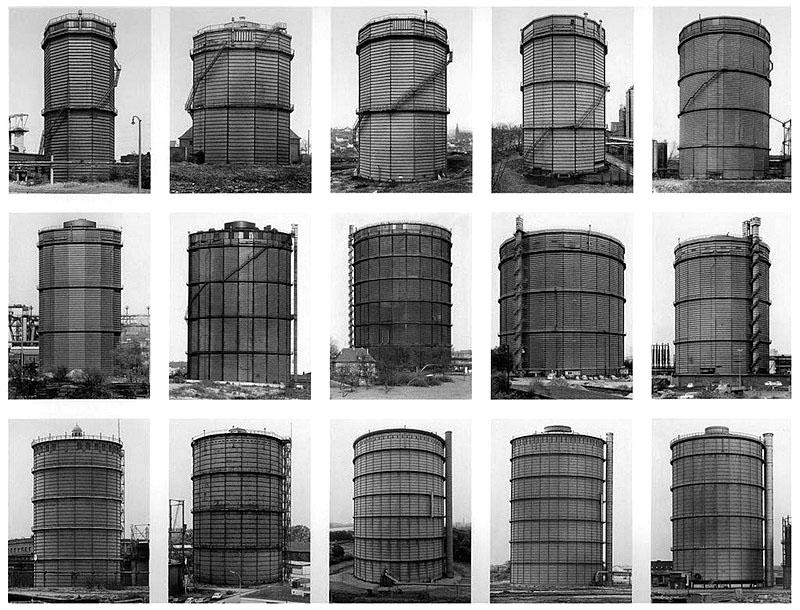

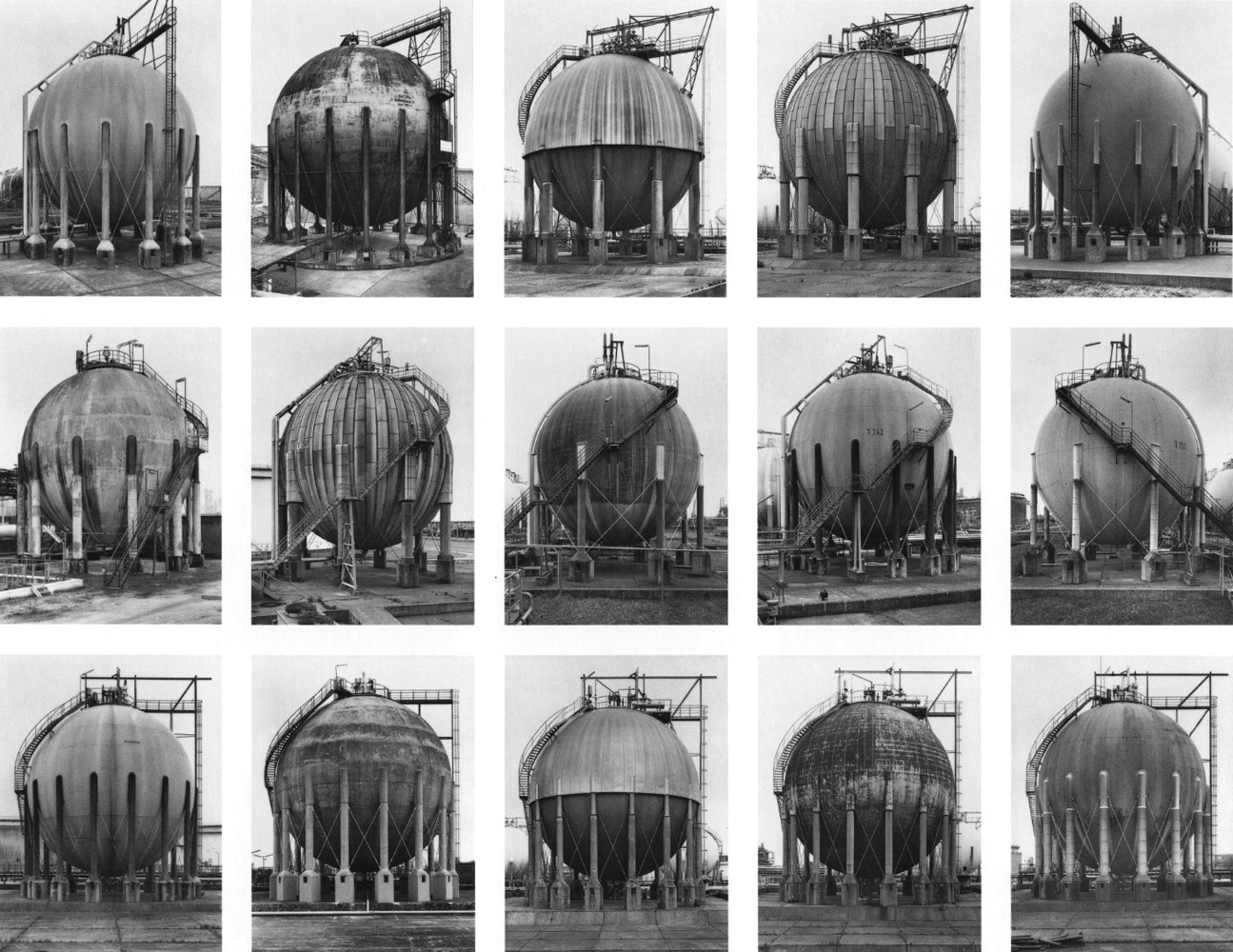

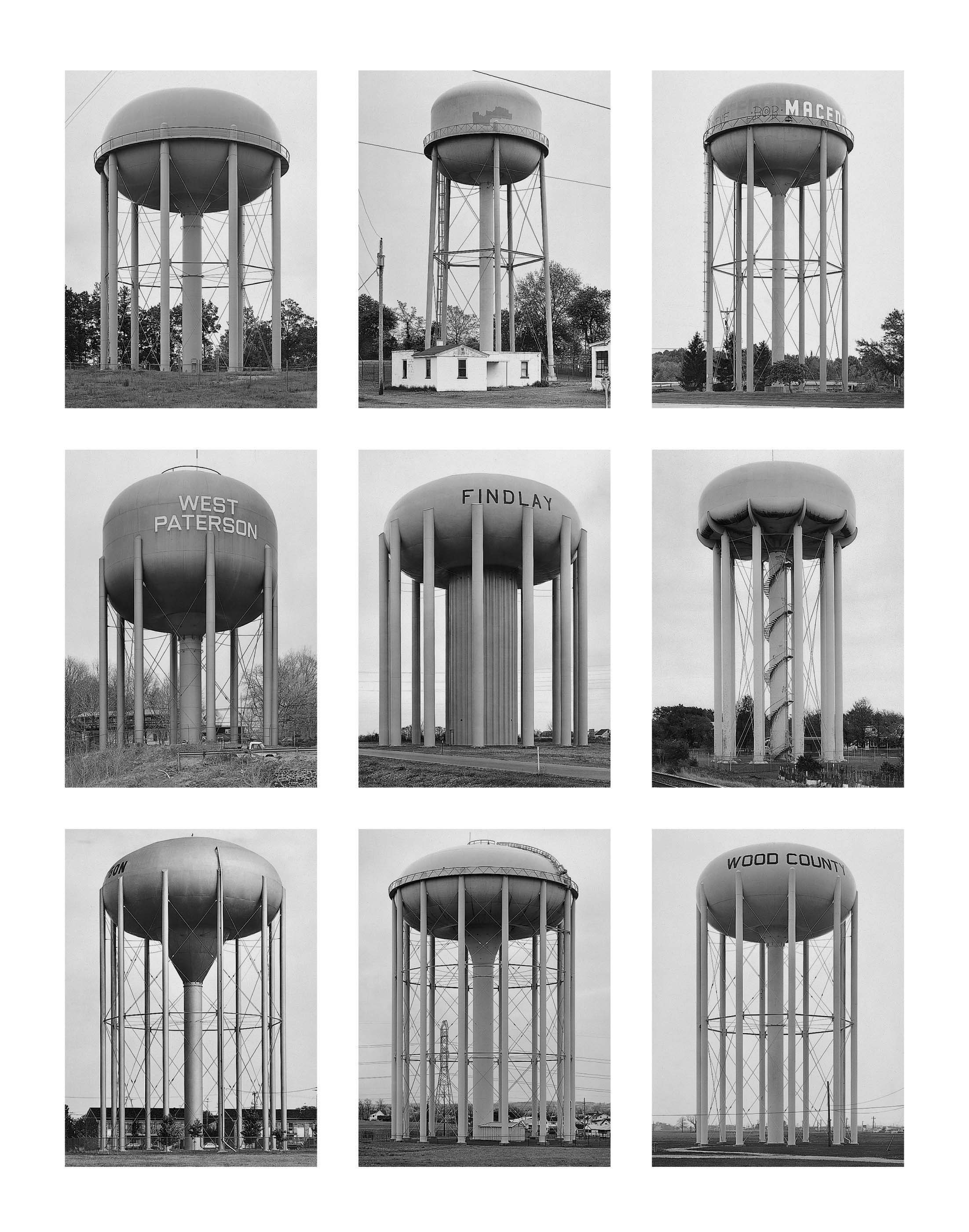

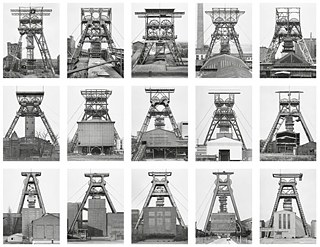

At the same time, the photographers Berndt and Hilla Becher were realizing an encyclopedic research on this subject, photographing hundreds of German industrial structures and cataloguing them by form and pattern. The artists predicted that the era of industrial magnificence was coming to an end and that those buildings would soon become relics of a glorious and failed past.

By using the term sculptures in the title “Anonyme Skulpture: Eine Typologie Technischer Bauten”, the Bechers explain how the process of formalization that takes place through framing and photographic “take” is absolutely consistent with the concept of readymade: Duchamp materially moves an object from reality to a cultural and artistic context; photography produces a similar shift by leaving the object where it is but making it portable through reproduction and printing.

In fact, in 1990 Becher won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale in the category of Sculpture, as if they had transformed industrial structures into sculptures, and had transported them to the Venetian pavilions.

In the same period Alain Touraine (La societé post-industrielle, 1969) and Daniel Bell (The Coming of post-industrial Society, 1973) used for the first time the term “post-industrial”. In economics it is used to indicate a society in which the work for the production of services has exceeded that of the manufacture of goods; but on a social, urban and cultural level it means that the industrial buildings themselves begin to lose their function and become (industrial) archaeology or are converted into cultural institutions in correspondence with the birth of the “cultural industry”.

This is the case of Centrale Montemartini (now a museum), Magazzini Generali (Istituto Superiore Antincendi), Vetrerie di Via Ostiense (Rettorato di Roma Tre), NABA (ex Enel building), the nearby Gasometro and the Ex Mattatoio (home to Roma Tre university, MACRO museum and festivals and cultural events).

POST-INDUSTRIAL ATONEMENT

Together with these structures and factories, the public attitude of trust and reverence for technological progress now belongs to a bygone era.

The urban dweller, aware of the tragedies and irreparable damage caused by industrialization, became distrustful of progress. The transformations of the places of industry in places of culture and the re-qualification of the abandon are greeted with relief, as if it allowed us to expiate the guilt of a past and disavowed behavior.

This reparation process goes beyond the post-industrial dynamics, and the list of physical and social architectures and landscapes whose shame is exorcised by transforming them into heritage, grows longer and longer.

That’s the case of the Berlin Wall, a section of which has changed its name to the East Side gallery, highlighting the total transformation into a cultural product.

That’s the case of the Iron Curtain museums scattered throughout the Balkans, or General Tito’s bunker which hosted some editions of the Bosnian art biennial, not far from Sarajevo.

It happened to an entire city in the case of Matera, called “the shame of Italy” by politicians of the Italian economic boom of the 50s and now recognized as a UNESCO World Heritage Site and appointed European Capital of Culture in 2019. (An interesting research has been carried out by a research collective called “Architecture of Shame”).

It happens to workers’ districts in Italian cities, as they are targeted by requalification and gentrification processes.

Ironically explaining this process, some artists have addressed this theme in relation to some Italian landscapes.

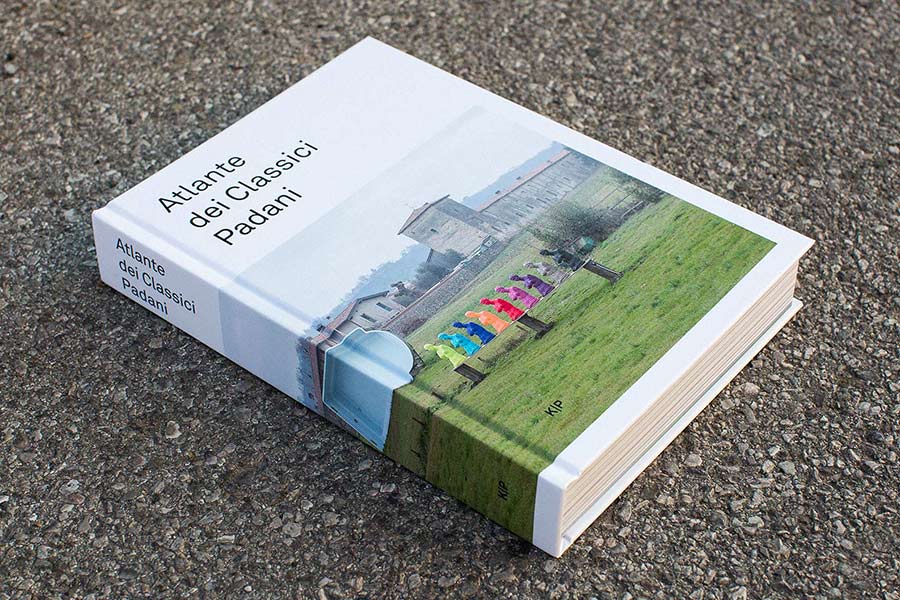

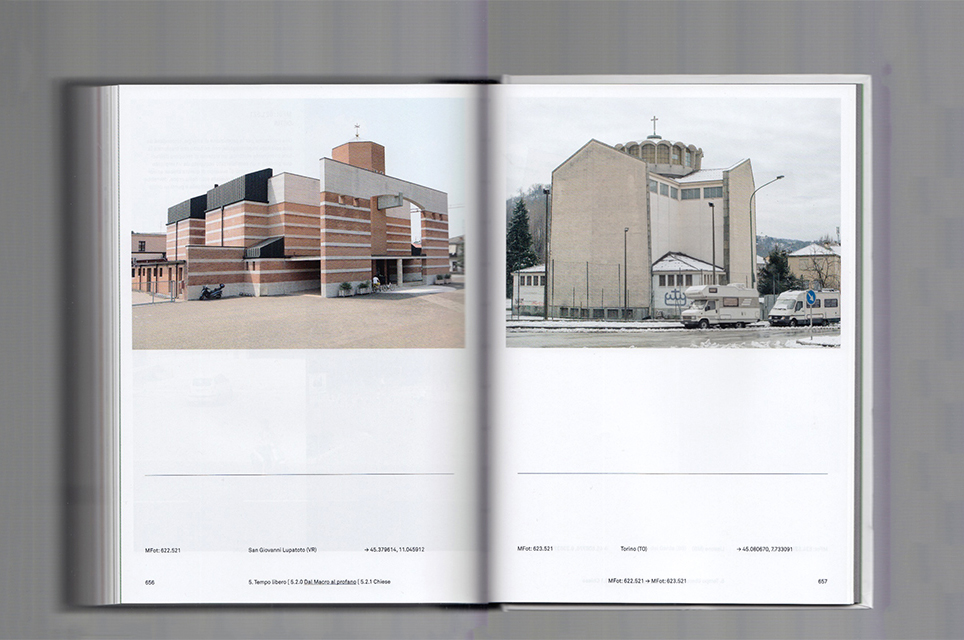

In Atlante Dei Classici Padani and in Incompiuto Siciliano we can verify concretely and directly how photographic representation can transform a territory or a landscape into a cultural product.

The over-diffusion of digital cameras and the consequent massification of the production of images in contemporary tourism further complicates the dialectic between shame and resemantization through redevelopment and photographic representation:

Auschwitz Memorial Museum recently had to publicly (on social media) condemn the behaviour of some visitors who replicated a social media photographic trend, in a self-defeating loop of redevelopment aimed at exorcising a historical shame and embarrassment for a photographic representation that is a direct effect of the same requalification.

A similar case also happened in Chernobyl where, following the success of the HBO miniseries on the relative nuclear disaster, there was a peak in both the number of tourists and the traffic images published on social media by influencers and Instagrammers.

The posts have become so frequent that Craig Mazin, the writer and producer behind the popular miniseries, took to his Twitter to tell people to be respectful: ‘It’s wonderful that #ChernobylHBO has inspired a wave of tourism to the Zone of Exclusion,’ he said in a Tuesday tweet . ‘But yes, I’ve seen the photos going around.

‘If you visit, please remember that a terrible tragedy occurred there. Comport yourselves with respect for all who suffered and sacrificed.’