OCCUPY PANORAMA: Iconographic re-appropriation vs commodification of landscape

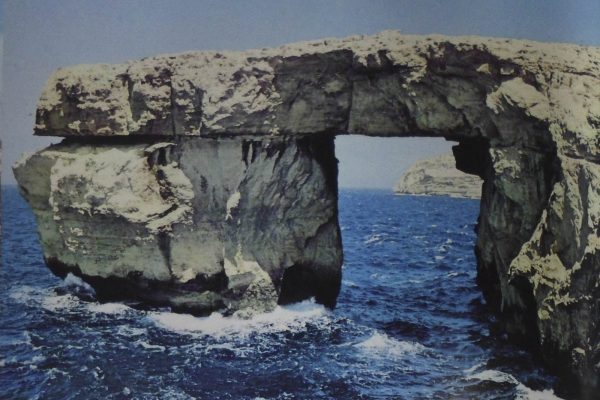

On the morning of 8 MARCH 2017, after a night of violent storms, the Azure Window, a natural monument (as well as an important tourist resource) of Malta, disappears under the waves and lies shattered on the seabed. We are in Dwejra, a town in the municipality of San Lawrenz in Gozo, the second largest island in the Maltese archipelago, here.

https://timesofmalta.com/articles/view/the-azure-window-lost-and-gone-forever.641810

https://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-39207196

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/03/08/world/europe/azure-window-malta-game-thrones.html

And of course the thousand of pictures made by tourists visiting Malta and Gozo:

search “Gozo Landmark” google images.

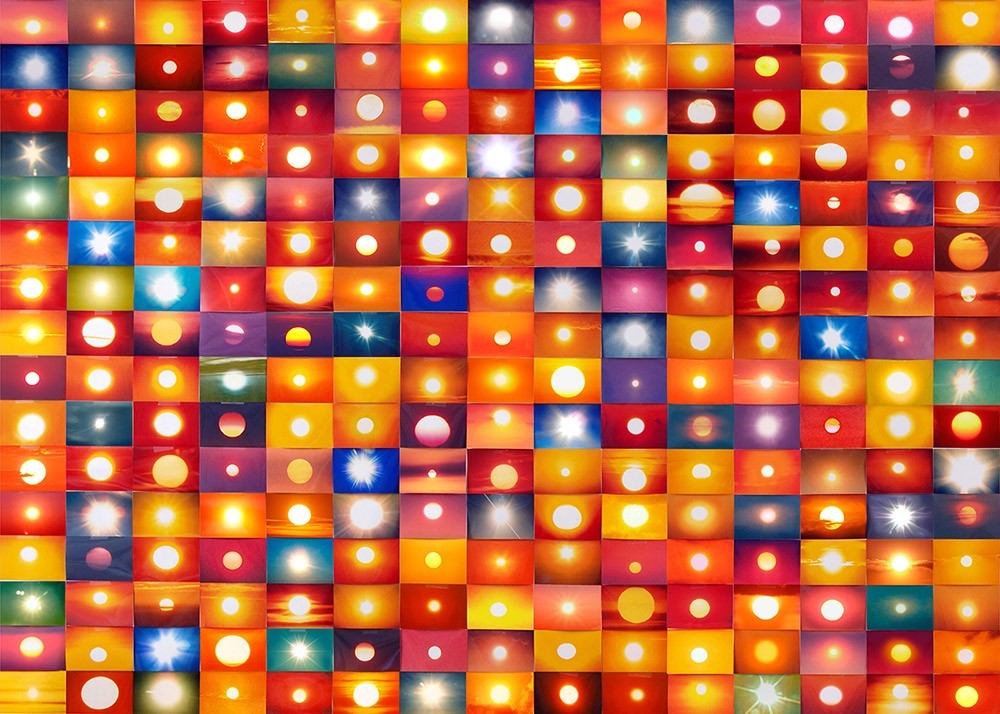

A work that show very well how tourism can create an homologation of a view of a particular landscape or monument is “Photo opportunity” by Corinne Vionnet (2005).

https://corinnevionnet.com/Photo-Opportunities

Penelope Umbrico, Suns from sunsets from Flickr (2006, ongoing)

http://www.penelopeumbrico.net/index.php/project/suns-from-sunsets-from-flickr/

Erik Kessels, 24hr in photos, 2011

https://www.erikkessels.com/24hrs-in-photos

https://otherpeoplesphotographs.wordpress.com

In San Lawrenz (748 inhabitants) arrives an army of tourists with cameras (1.5 million from January to August 2017 for example), visiting Gozo with the specific intent of photographing the natural wonders, first of all the Azure Window.

Even by mobilizing the entire population of Gozo (about 40,000 inhabitants), the photographic firepower would be unfavorable by 1 to 35.

John Urry, sociologist and expert in tourism studies, explain this in his book “The Tourist Gaze” with the theory of markers: we desire to visit a certain place depending on the amount of MARKERS we are able to link to that spot: information that we will find good food or nice views and good air are markers; the fact that an author we like talked about that location in one of his book is a marker; a postcard sent by a friend who visited that spot is a marker contributing to trigger our desire to visit it. A million digital postcards raining on us through our screens and device it’s a never-ending, automatic, self-updating, permanent, auto-trophic marker.

Local politicians realized that no TOURISM PROMOTION CAMPAIGN could compete with such a photographic fire-power. That it was free and that they were loosing it along with the limestone arch. That the territory was loosing not only a limestone arch but also an important economic resource.

Photography to sell landscape

The link between image and production system dates back to the very birth of the medium and coincides with the spread of the particular spirit of the nineteenth-twentieth century that placed technological progress and discovery at the core of human history.

The invention of photography itself was part of that particular approach: it is indeed not the result of individual and sudden inventiveness but the product of studies and entrepreneurial initiative of different players who shared the need to mechanize the production of images alongside that of goods and artifacts.

All of them, rather than photographers or artists were inventors, entrepreneurs, “modern” men, driven by that spirit an idea of Progress..

Joseph-Nicéphore Niepce, one of the pioneers of the photographic process (which he first experimented with in 1827), had also invented with his brother Claude a steam engine that they had used to move a river boat. He was interested in the possibility of fixing the image “photographically” because he wanted to apply the invention to the engraving process, very popular in France in publishing and crafts.

Thomas Wedgewood was already experimenting with sunlight printing around 1800 to try to serialize the printing of decorative images on the products of the family company, the famous Wedgewood Pottery.

Even Louis Daguerre, considered the official inventor of photography because of the statalization and publication of his invention by the French government in 1837, was indeed a painter but was certainly better known for his “diorama”, a theatrical machine that allowed to change theatre sceneries through the combined use of semi-transparent curtains and the light from windows and candles.

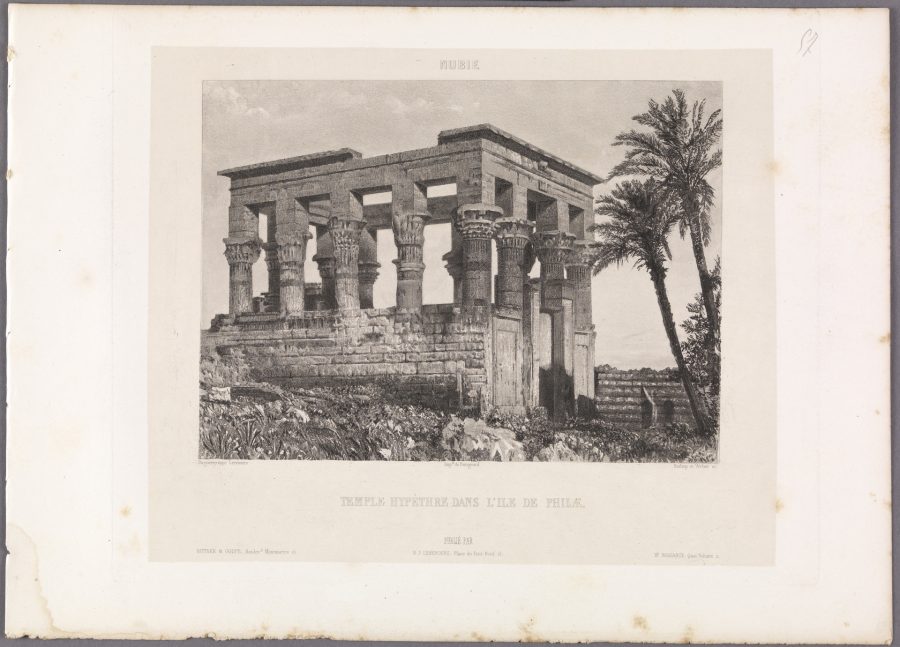

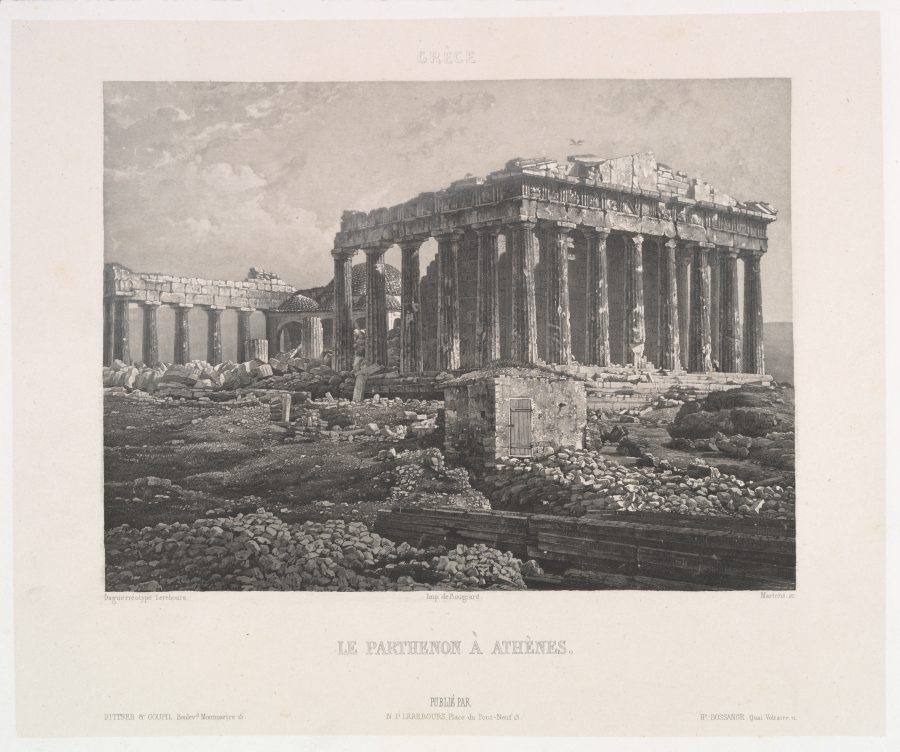

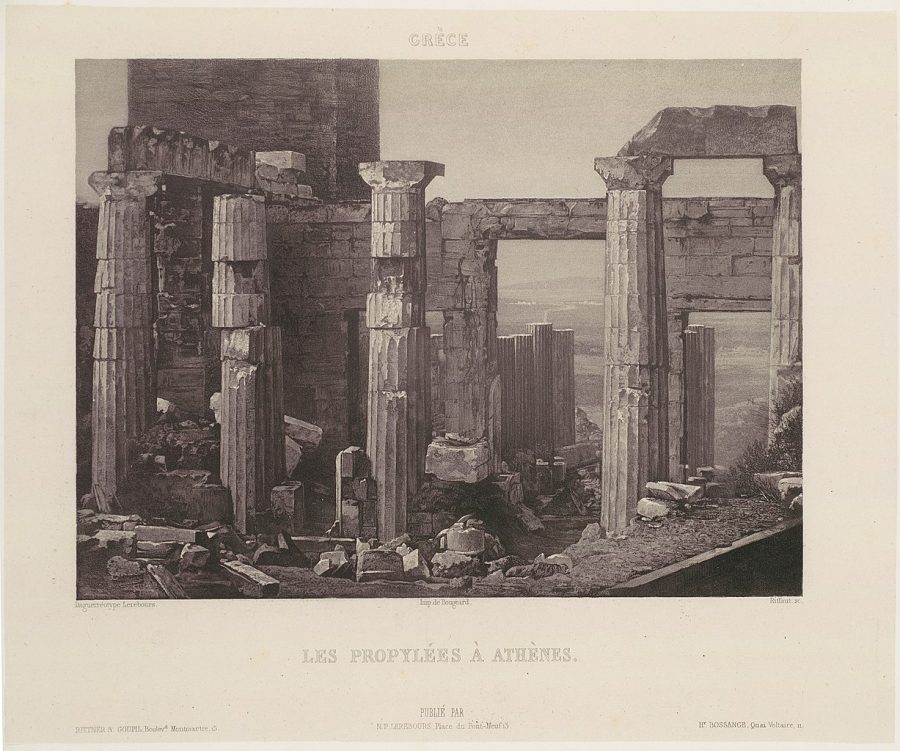

Even the first uses of photography were fueled by an exquisitely entrepreneurial attitude, and were closely linked to the concept of progress, in its meaning of “discovery” and “exploration of the unexplored”. FIRST THING PHOTOGRAPHY DID WAS TO SELL LANDSCAPES.

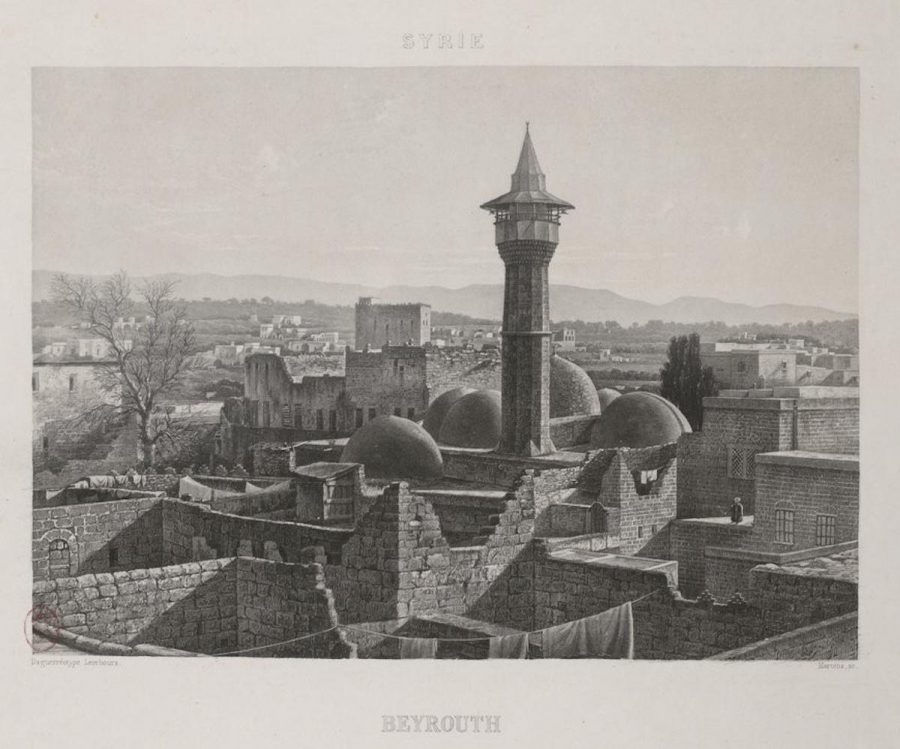

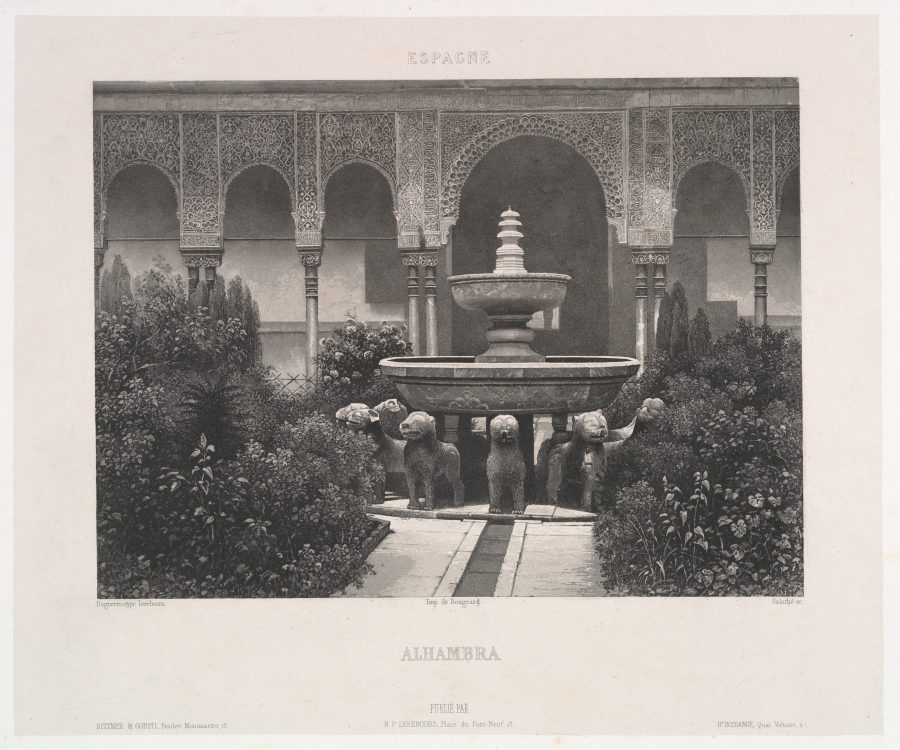

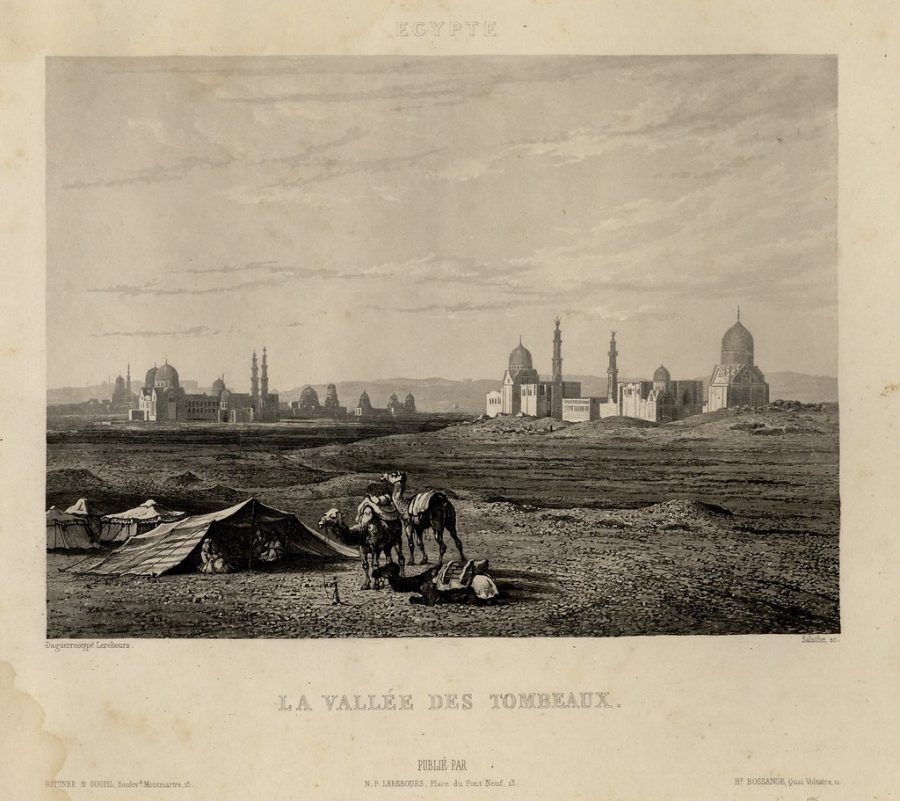

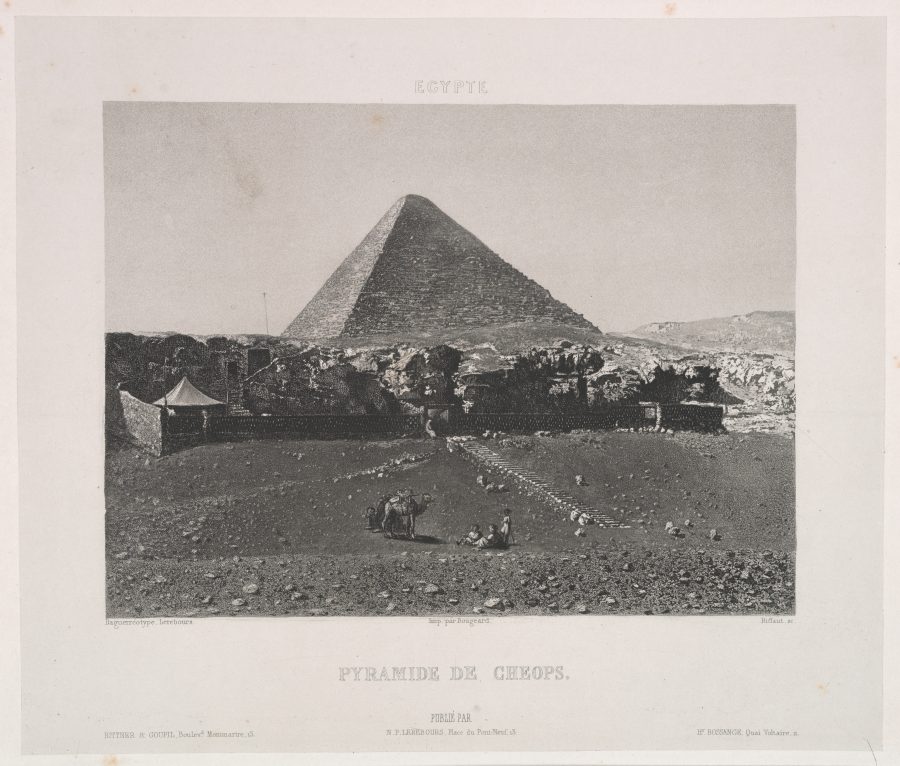

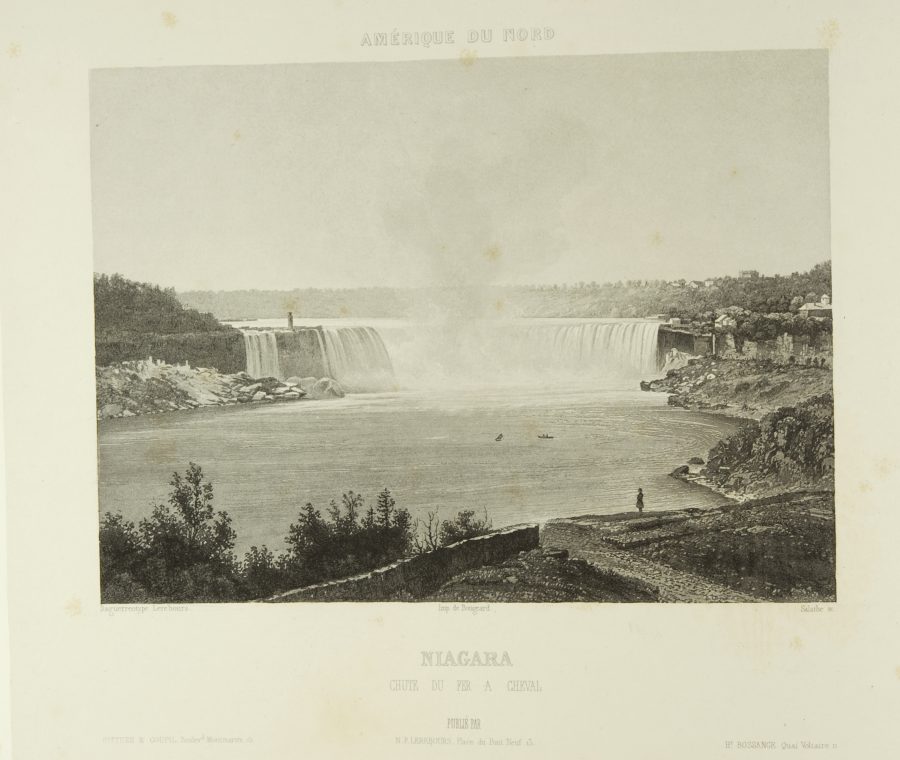

In 1840 (1 years after the publication of Daguerre’s findings!) the publisher N.M.P. Lerebours produced the Excursions Daguerriennes, a collection of views of landscapes and monuments from Europe, from the Middle East and America which were tremendously successful because they allowed those who could not afford to travel to “see” distant and exotic places for the first time.

Landscapes is evidently turned into an object, something that you can bring somewhere else in order to show it (or possibly print and sell to be shipped back home, like i.e. …). Which is, by the way, what photography does TRANSFORM REALITY INTO A 2D OBJECT. To report things

And when we talk about discovery we mean not only geographical ones but also technological: photography was not only a product of industrial revolution, but also its greatest propaganda tool: photography sang the technological progress of the new man made in the new world.

John Edwin Mayall

The Crystal Palace at Hyde Park, London, American Pavillon, 1851

Civil war

https://www.loc.gov/pictures/search/?st=grid&co=cwp

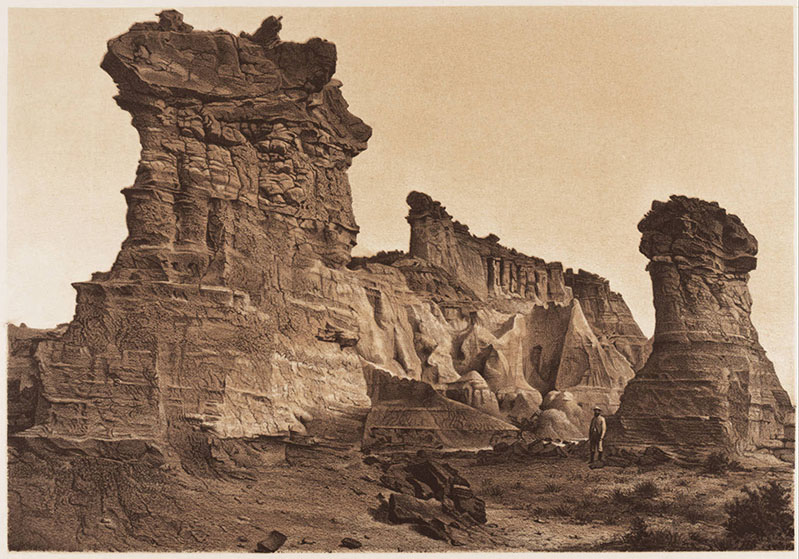

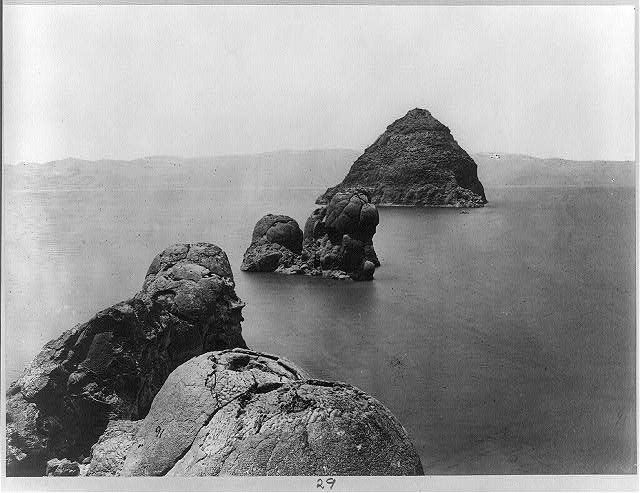

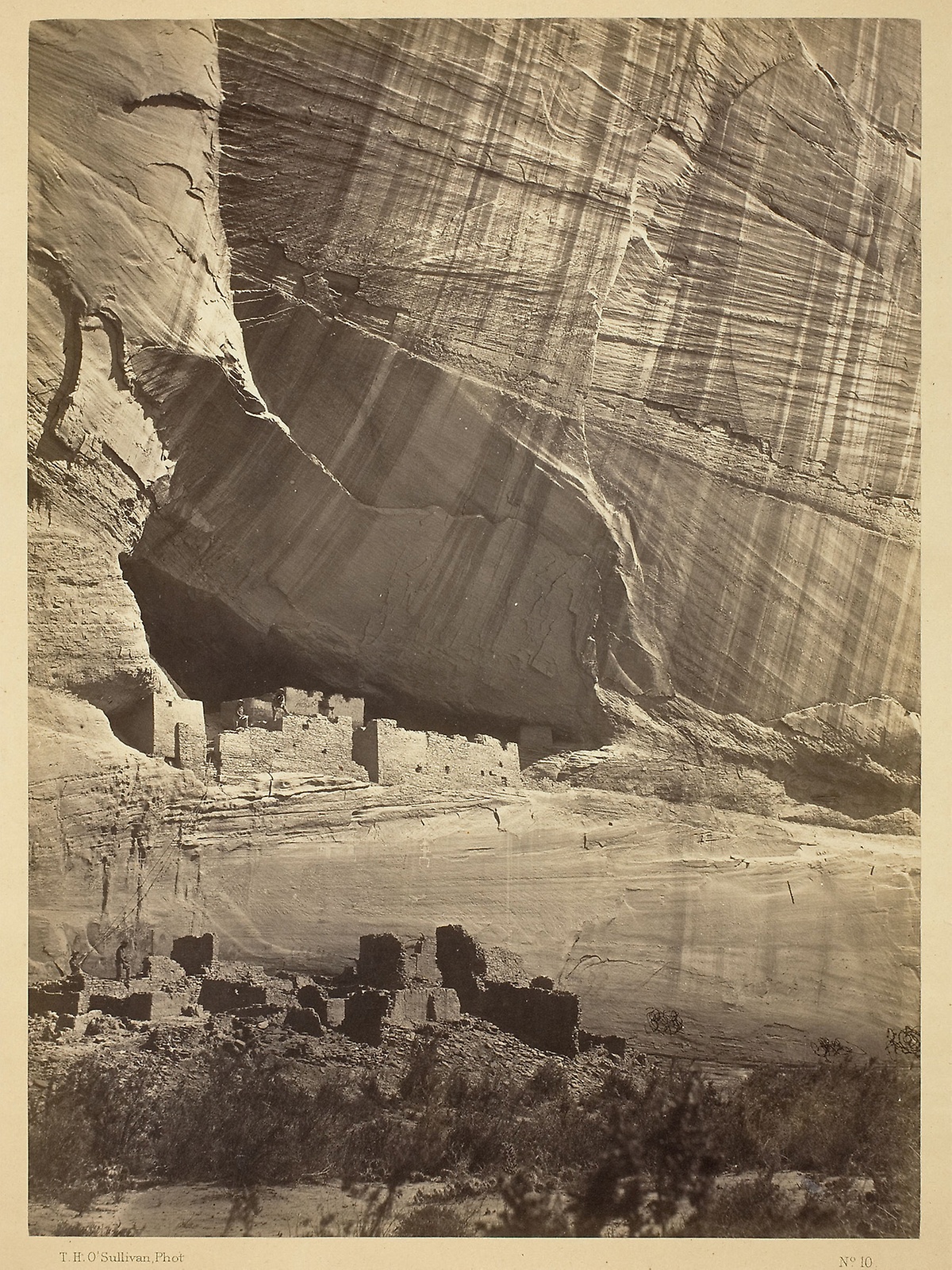

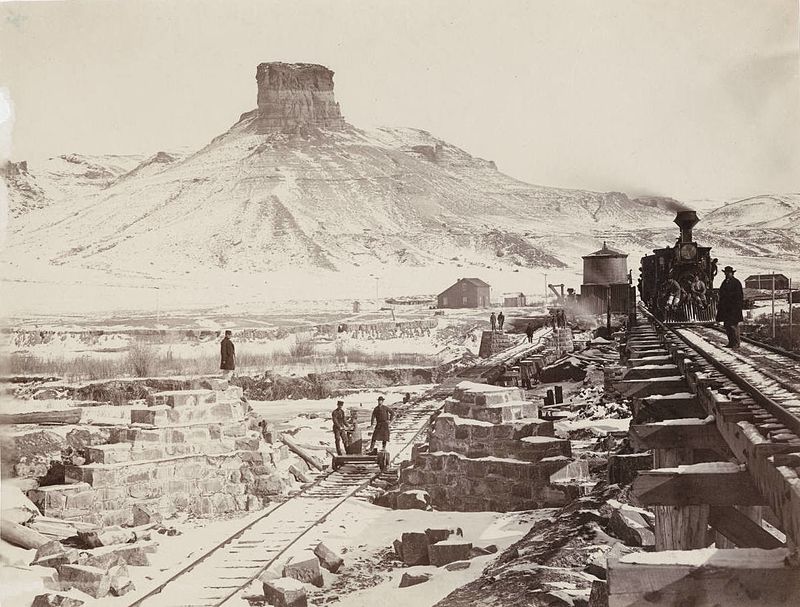

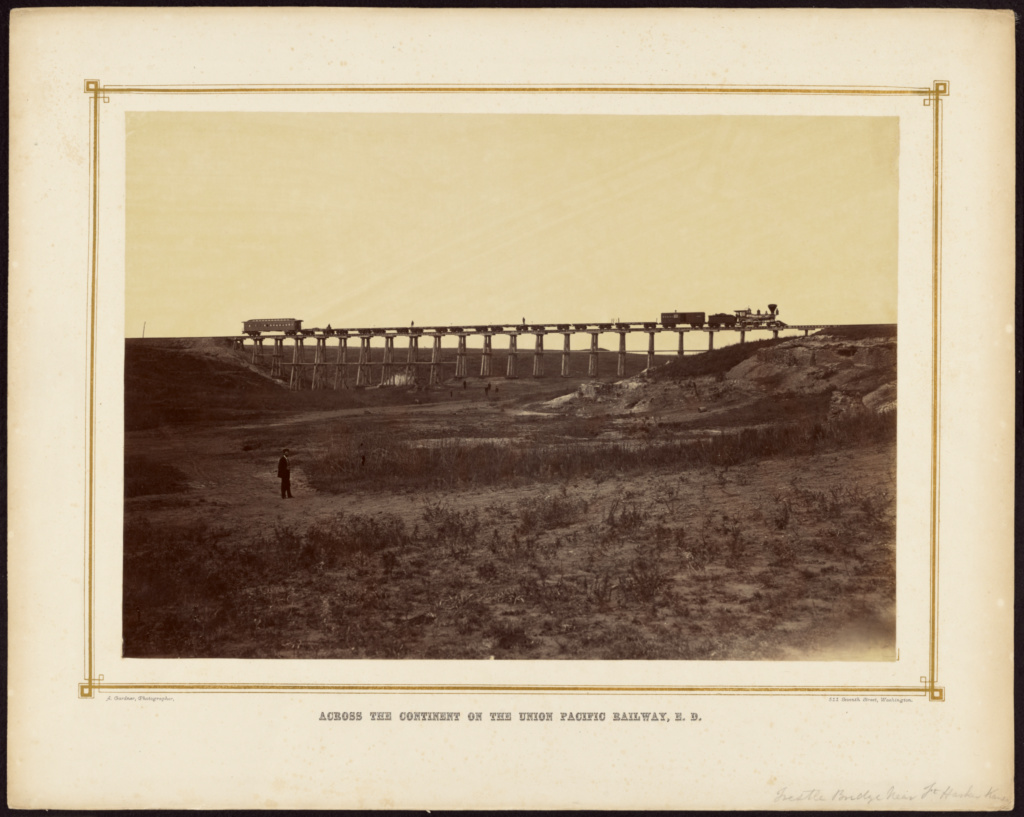

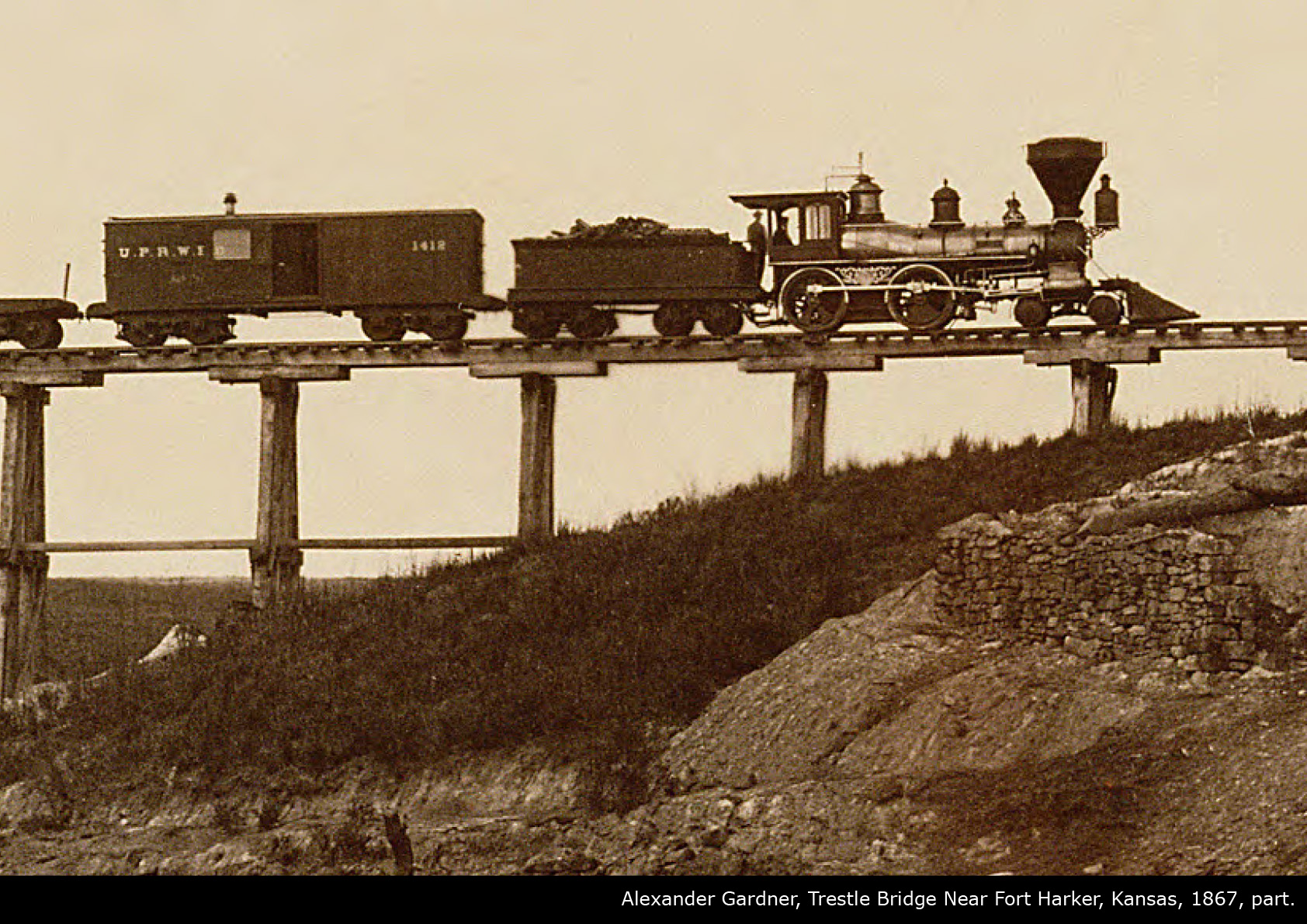

Photography was used as a proof of the exploration of the American West: a group of photographers was engaged in exploratory campaigns funded by the winners of the American Civil War in order to document the beauty and possibilities of the newborn state.

Those photographs, printed in New York and other fast-growing American economic cities, showed entrepreneurs and investors the land and resources in which they could invest to continue the venture.

Clarence King Expeditions at the 40° parallel

George Wheeler Expedition, west of the 100° meridian

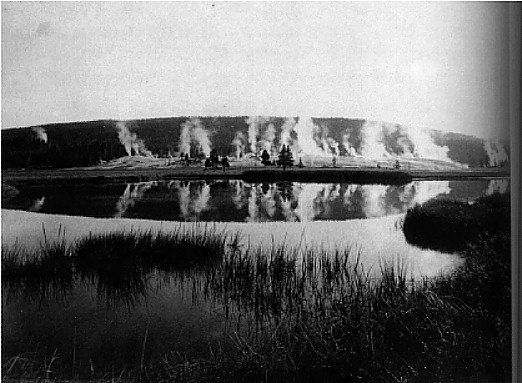

The Beehive group of geysers, Yellowstone Park, 1872. Hayden Geological and Geographical expedition

Summit of Yupiter Terraces, 1871.

Hayden Geological and Geographical expedition

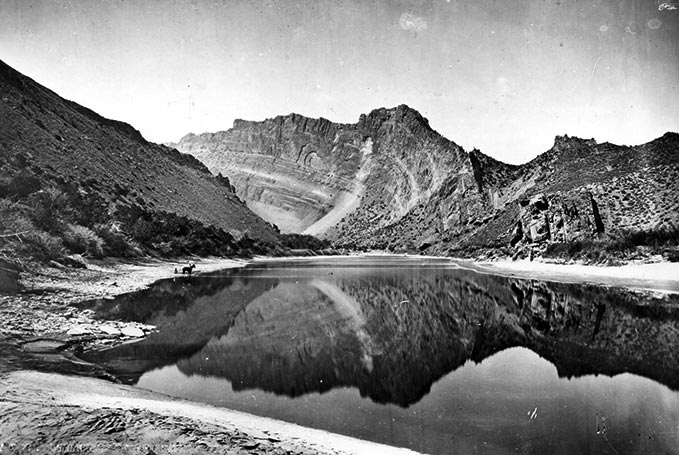

Rocky Mountains

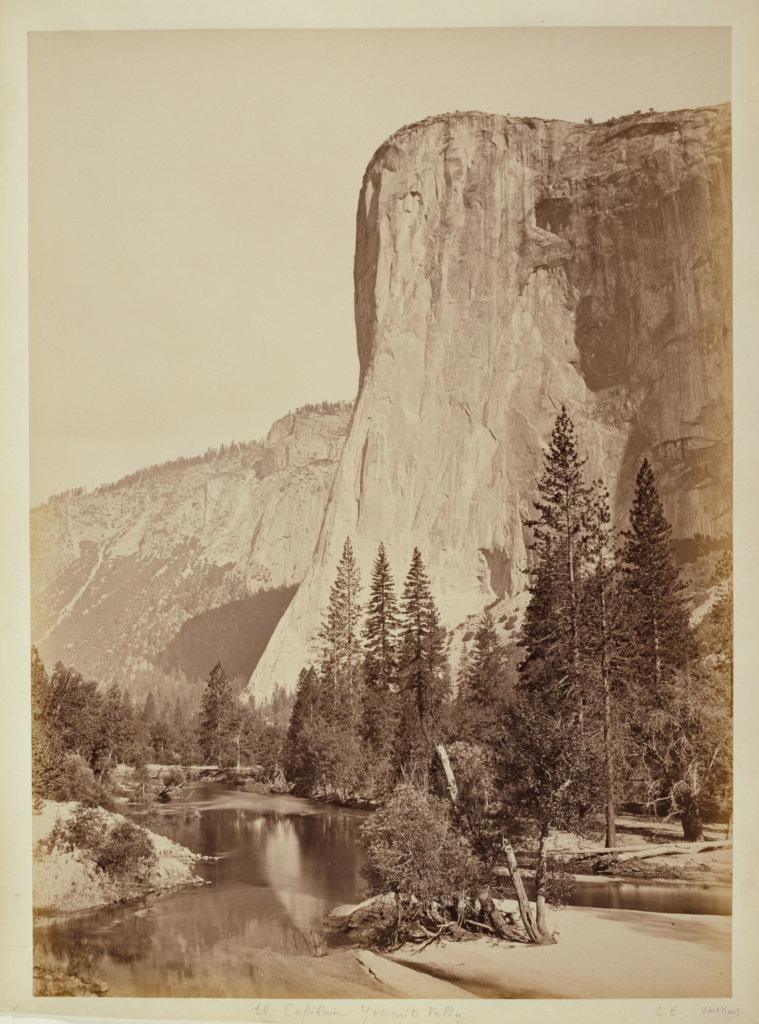

El Capitan, Yosemite, 1865

Yosemite, 1865

Carleton Watkins, Yosemite Valley, California, ca.1865

Carleton Watkins, Yosemite Valley, California, ca.1865

IMAGERY-IMAGINATION

https://images.nasa.gov

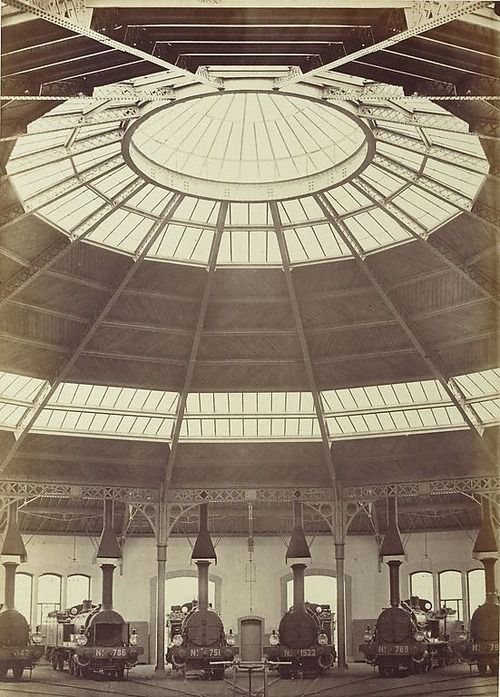

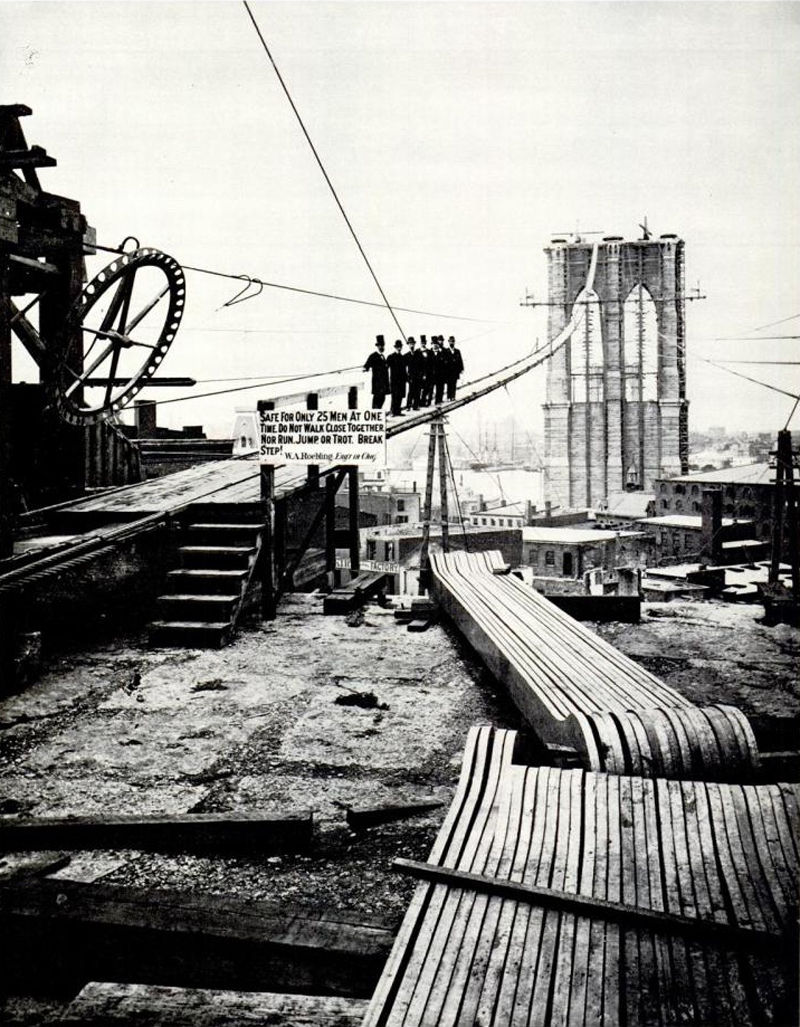

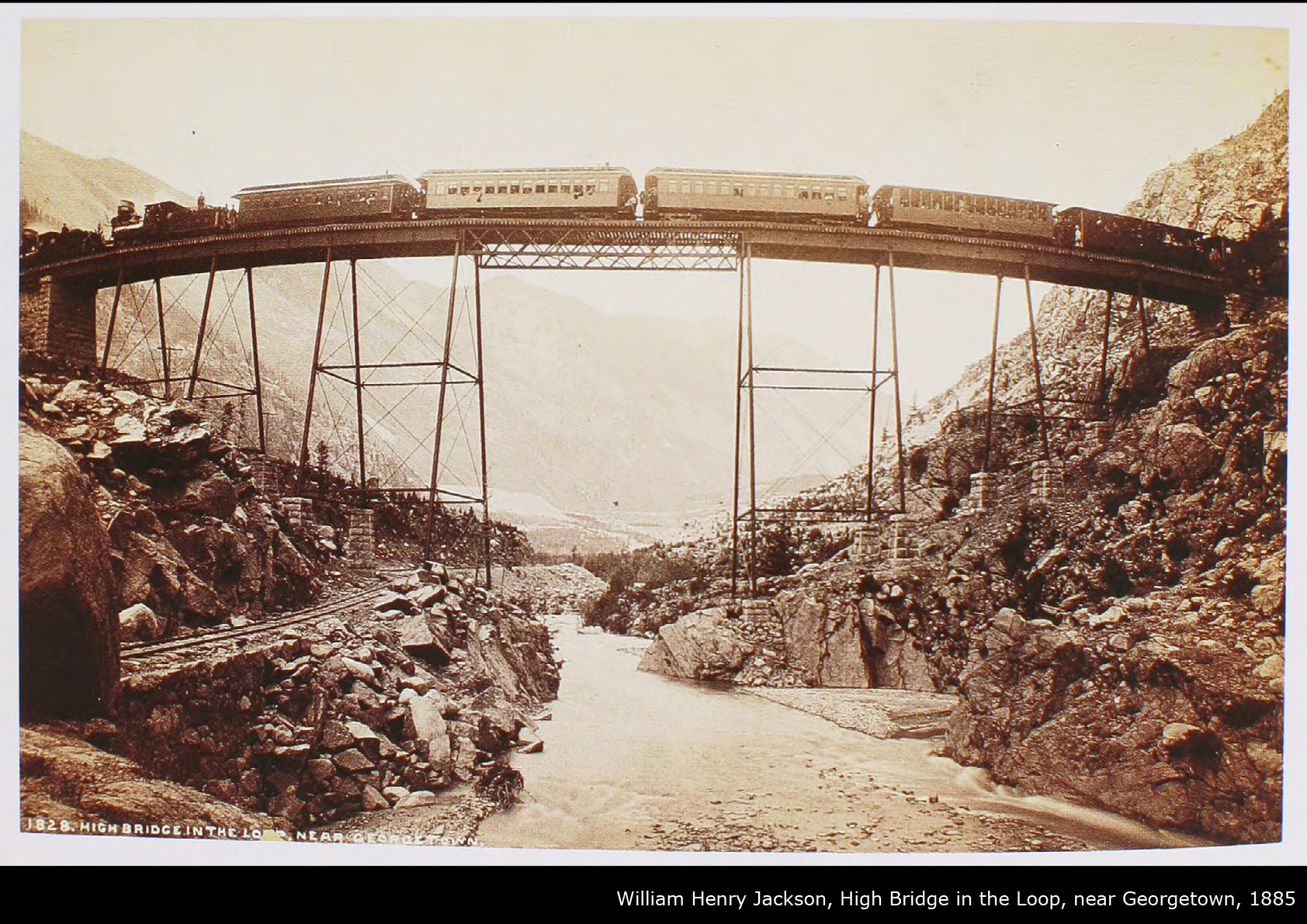

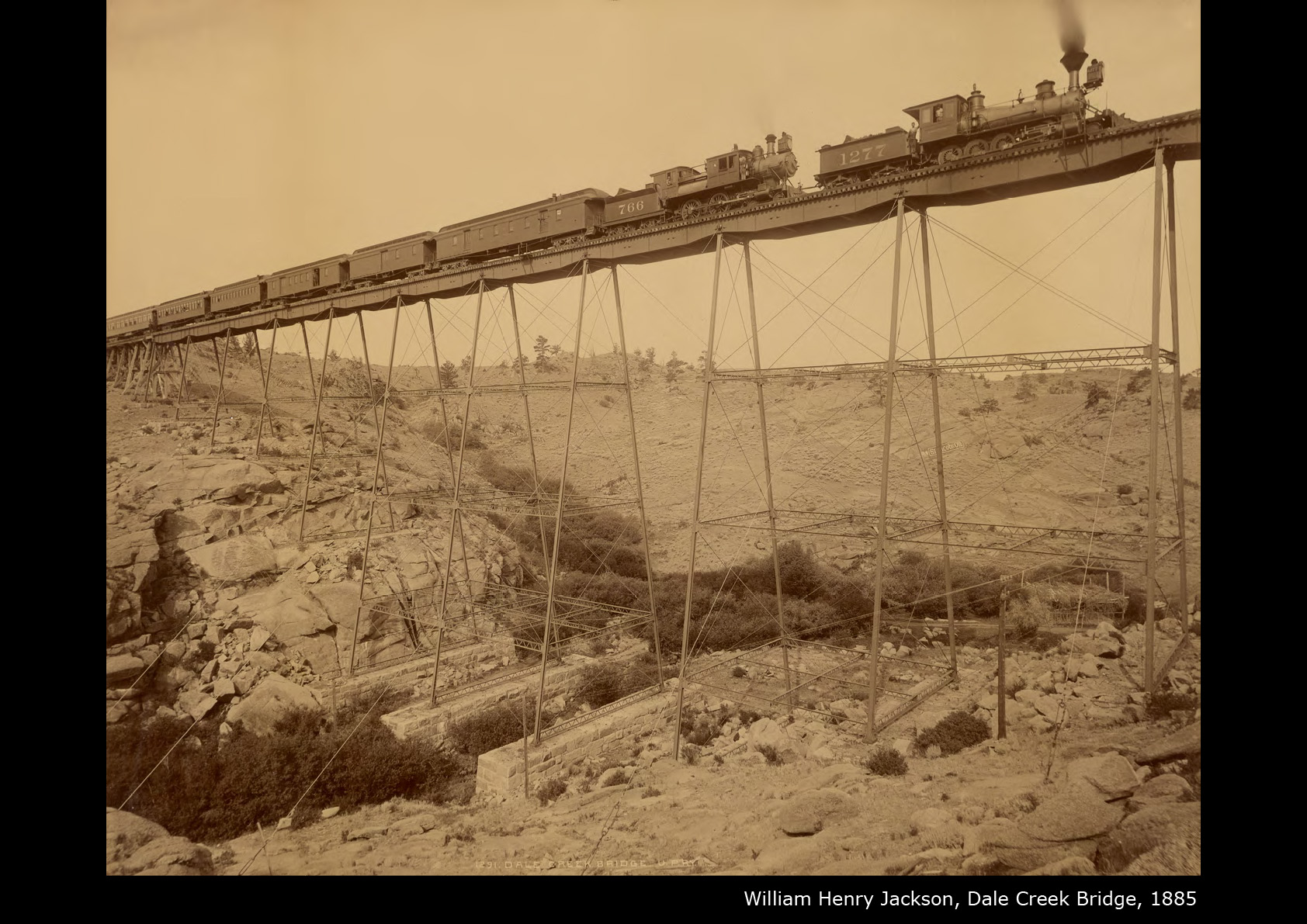

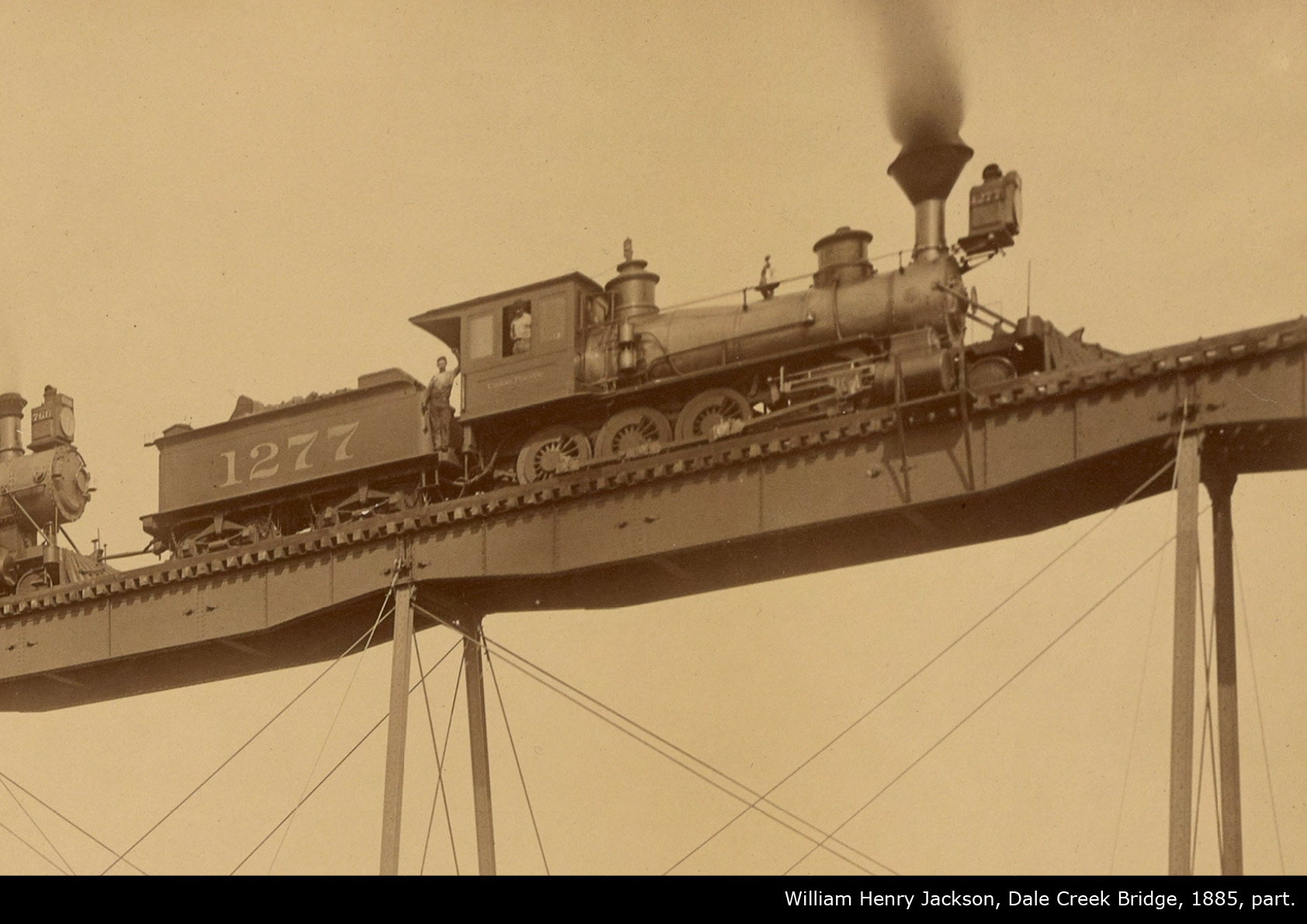

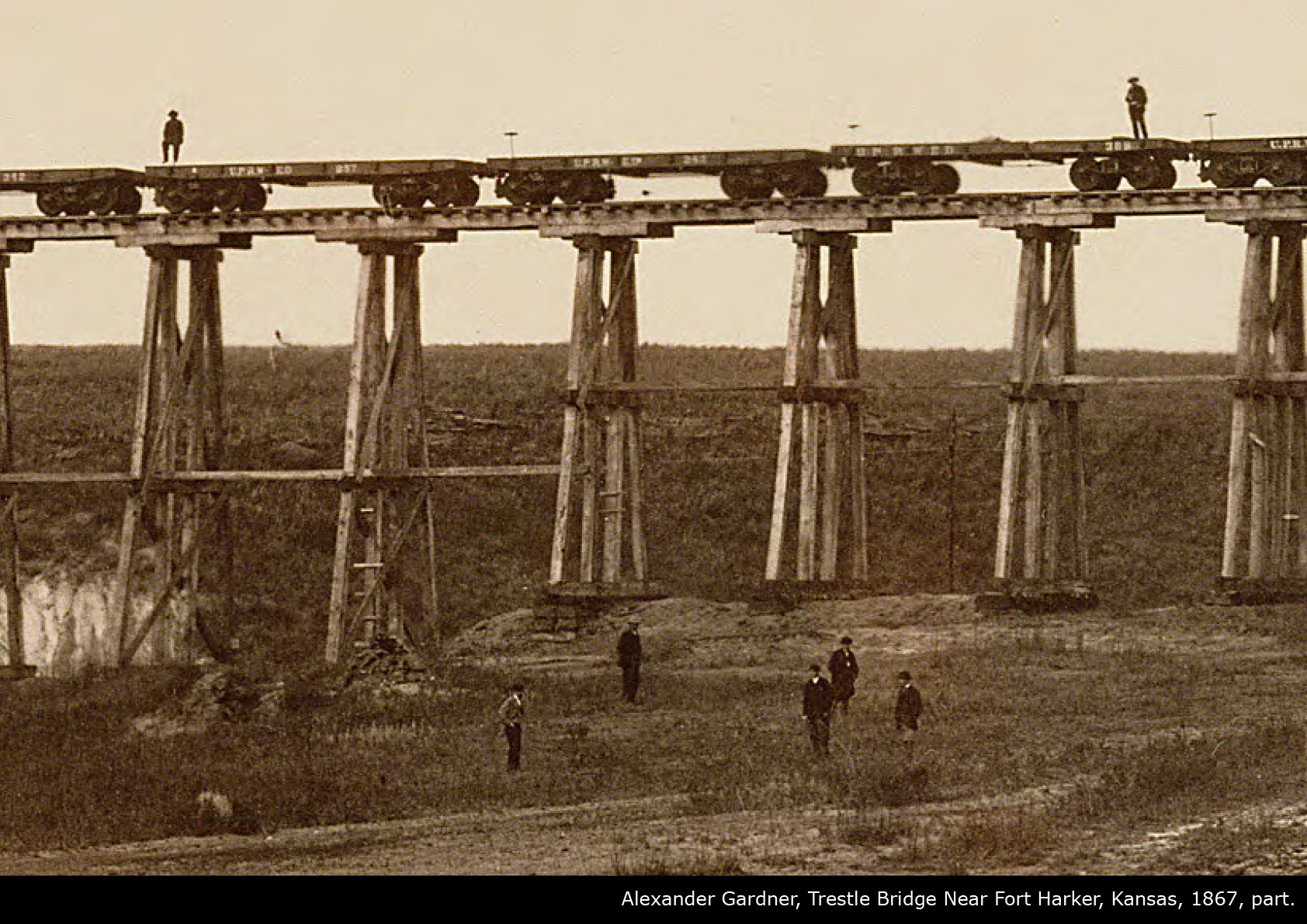

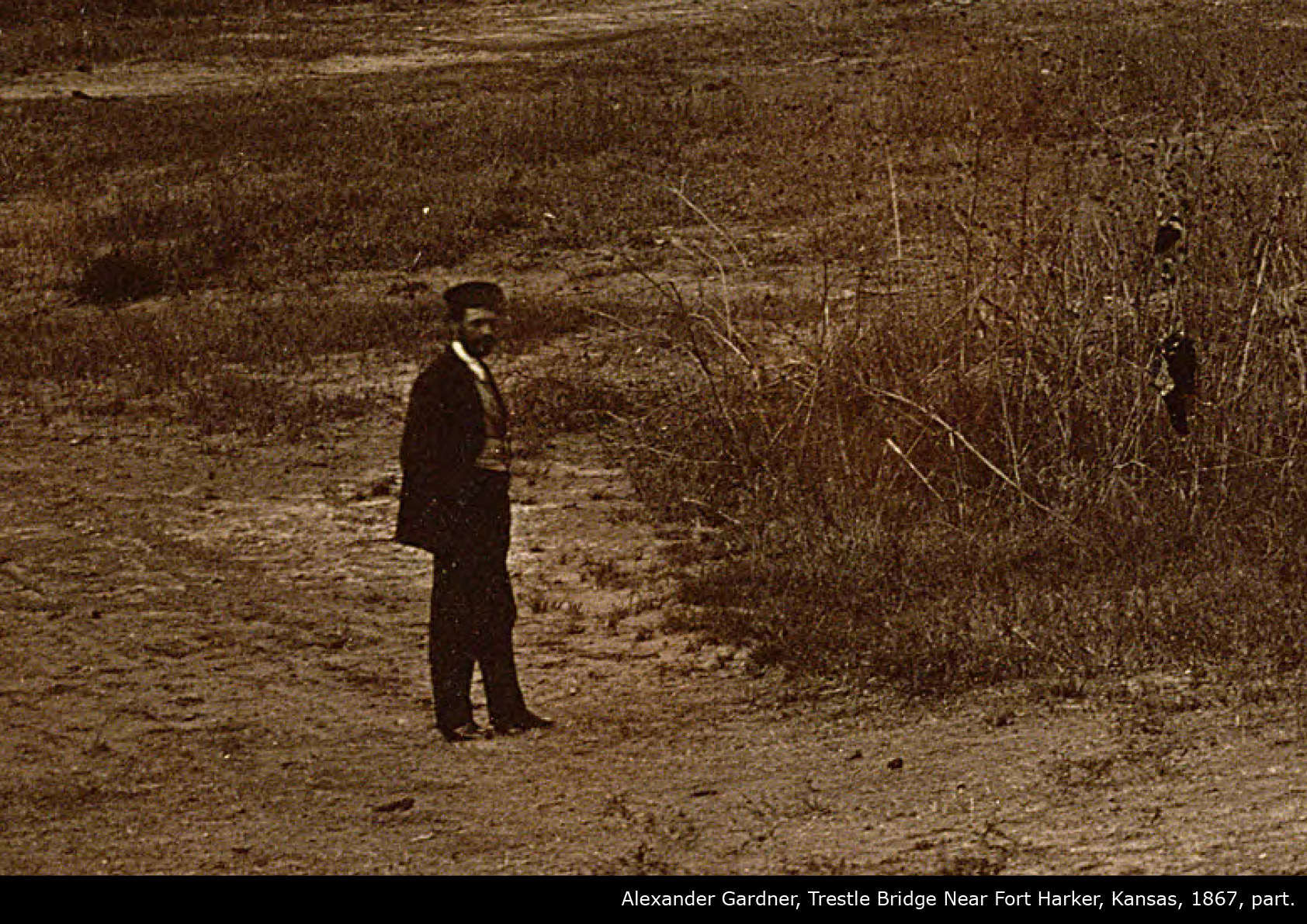

Photography was used to tell the story of another great symbol of human progress: THE STEAM LOCOMOTIVE AND THE RAILROAD. Together they embodied the myth: working on the construction of the railway and posing for the photographer were two ways to be part of that extraordinary moment in history.

Andrew J. Russell, “East shaking hands with West”, Meeting of the Rails, Promontory Point Utah, 1869

Enlarge: https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/aa/East_west_shaking_hands_by_russell.jpg

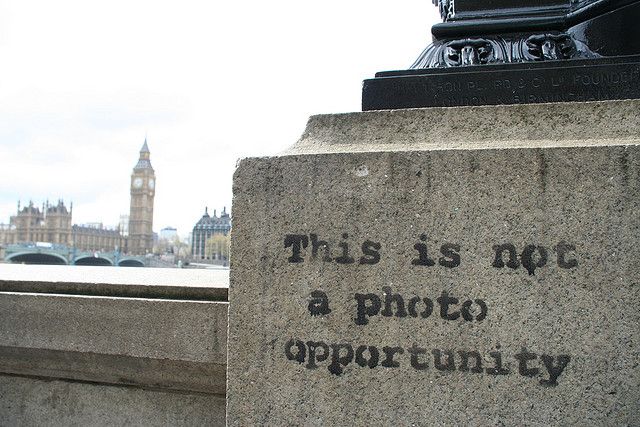

These pictures make even clearer something we suspected since the origin of the medium: photography is NOT AN INNOCENT BYSTANDER OF REALITY. It affects the reality both physically (moving trains, triggering behaviours of people and tourists in our case) and on a semiotic level: once we frame something in a photography we assign a different meaning to the framed reality.

These pictures also testify the importance that photography had in the century of technological progress. We can see it by the DEDICATION that both the subjects in the pictures and the photographers put in the making of those grand views: everything needs to be perfect, dust off the clothes, wear hats, stop trains. The camera was so important that the whole landscape needed to be neat and clean for the photo. Something about photos that we have gradually lost while we were getting accustomed to contemporaneity and to cameras. And now we’re not only uninterested but we find it annoying when we spot someone that is photographing us.

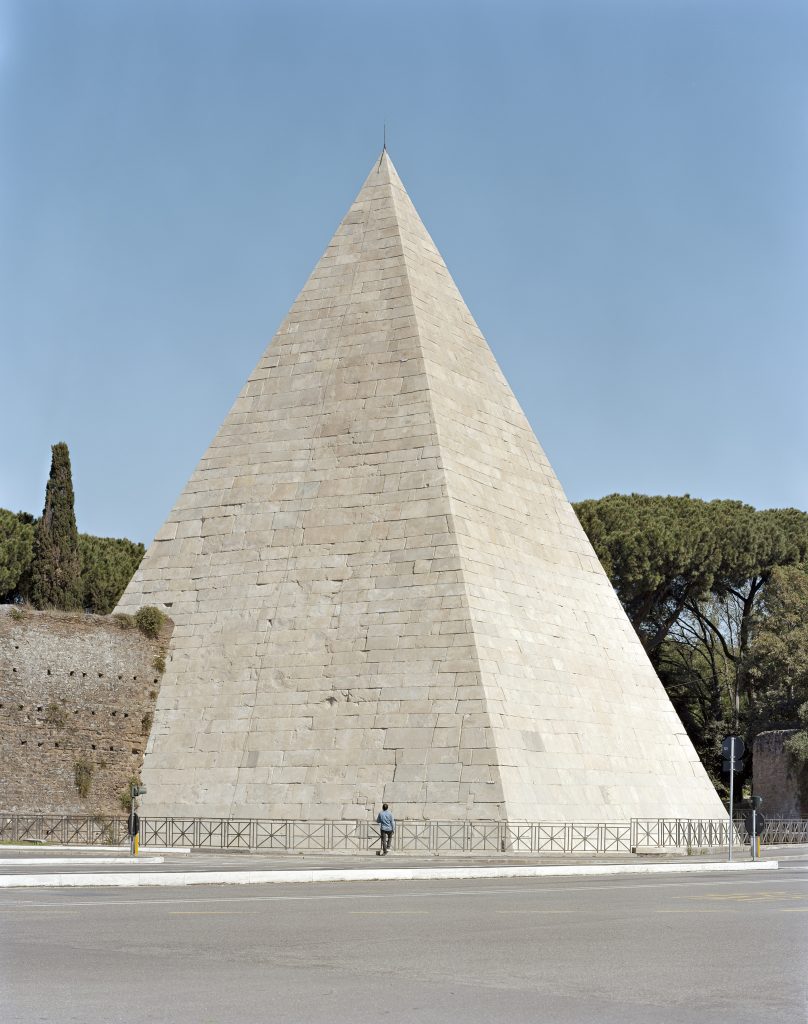

With Studio Figure we addressed this topic in a series of views of Rome that we did during the first lockdown.

“Rome. 22 Large-Format Color Views”

Some views of Rome monuments, squares and palaces, which have been reproduced and re-photographed over and over throughout history, find their prototypes in XIXth century work of Italian proto-photographers and Euorpean proto-tourists, who were unconsciously setting the paradigms for future popular representation of the “eternal city”.

At the time, to be the subject of a photograph was considered a “modern” experience, an opportunity to feel the spirit of the glorious (capital-lettered) Progress of XIXth century. The medium deserved respect and attention: people used to stop their business, dust themselves off and pose, as they knew that, by being in a photograph, they would be part of that Progress.

And landscape was supposed to show the same respect and sanctity of the photographic moment: it had to look neat and clean, all figures and forms carefully placed, no error, no figurative incident that could turn away the attention on something beyond the plain image.

That’s why those archetypal XIXth century views of Rome have a particular, powerful aura. A feeling that became harder and harder to reproduce as contemporaneity (with its cars, tourists and subsequent commodification of landscape) sneaked in.

We used to wander in the city center in Rome during Spring 2020, as Covid-19 overwhelmed Italy, sensing for the first time that same wonder and aura in its monuments and squares.

The weird, violent loss of the “contemporary” was revealing us the ghosts of that XIXth century magnificence.

The composition, practice, technology we used in this work (as well as the layout and title of the portfolio we attach) is thoroughly inspired by those archetypical popular views of Rome.

Again, once we frame something in a photography we assign a different meaning to the framed reality. Which is something that photographers realized with increasing clarity throughout the history of the medium:

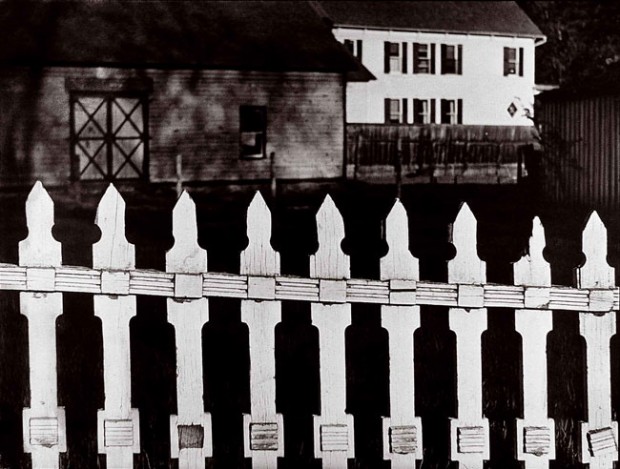

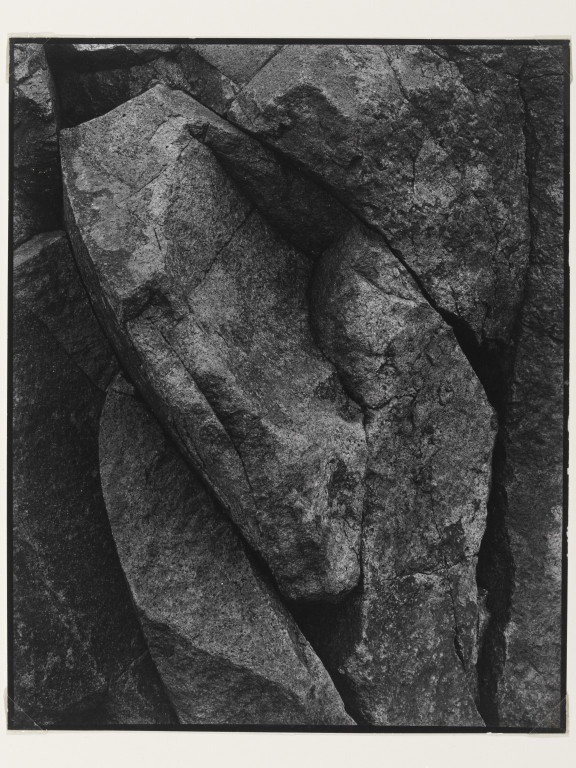

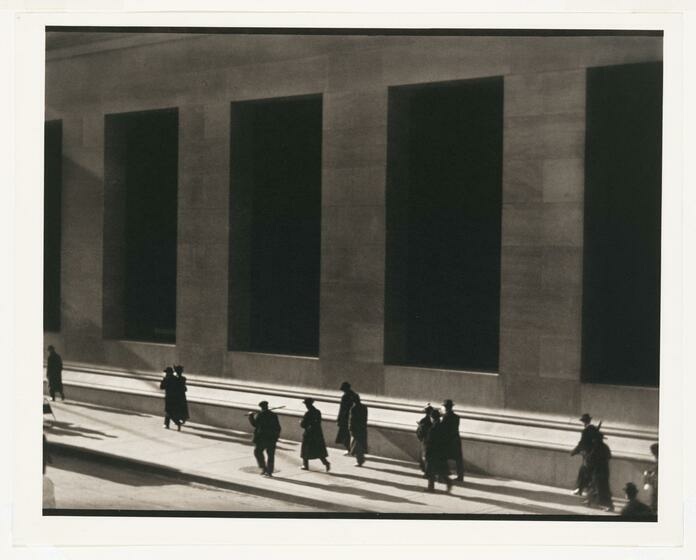

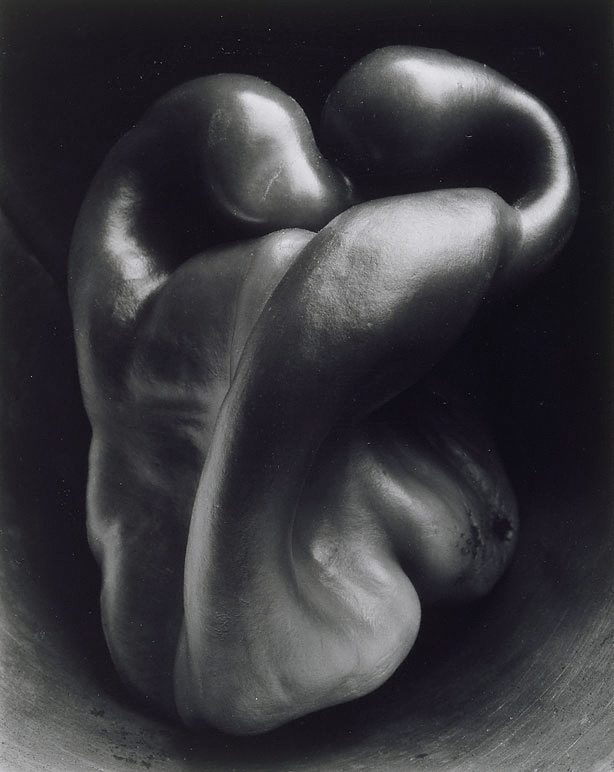

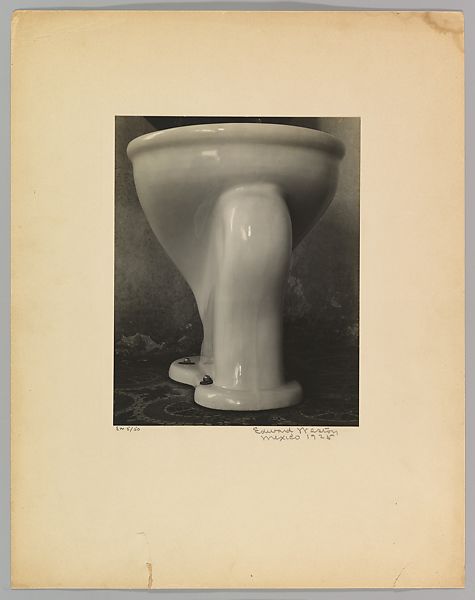

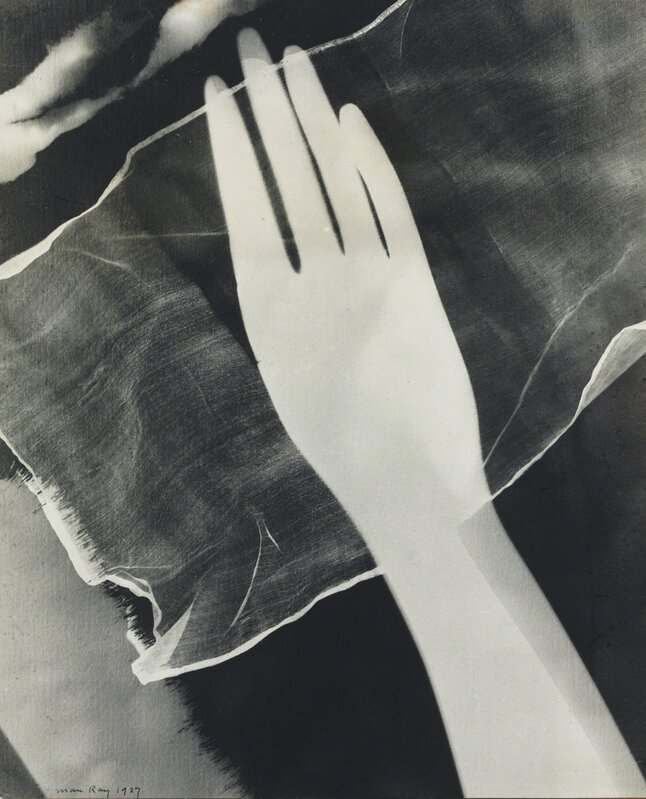

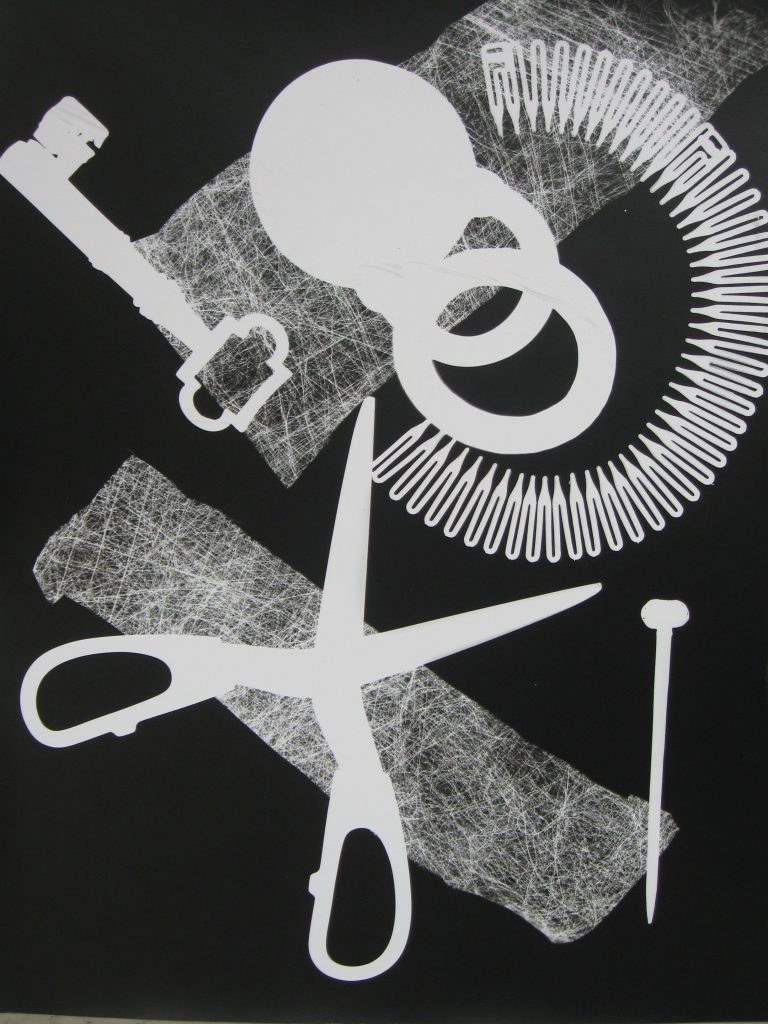

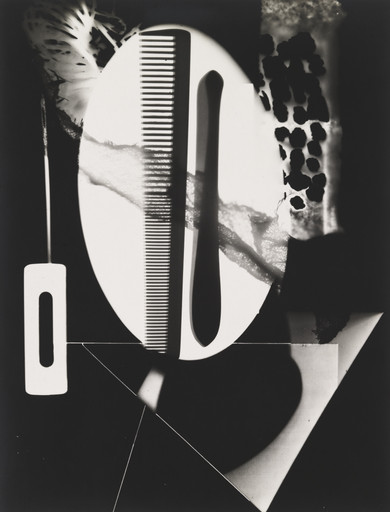

At the beginning of XXth century, artists such as Joseph Stieglitz, Edward Weston or Walker Evans, Paul Strand were proposing a “STRAIGHT” approach to photography, showing how the medium was able to produce art even by choosing everyday subjects. Those artist were reacting to the pictorial approach of the second half of XIXth century during which many photographer were using methods and chemicals in order to make their photos look like paintings and be considered as art.

In “straight” photographers work there is no need for tricks and embellishment and that is a precise statement:

the act of framing through photography triggers a process of formalization, aestethicization, monumentalization – and also objectification and commodification the subject.

“Excusado” shows a further statement by those artists: not only everyday object, but also the most ordinary or even the most despised objects may become art or monument, when they are chosen as a subject fo a photographic or artistic practice.

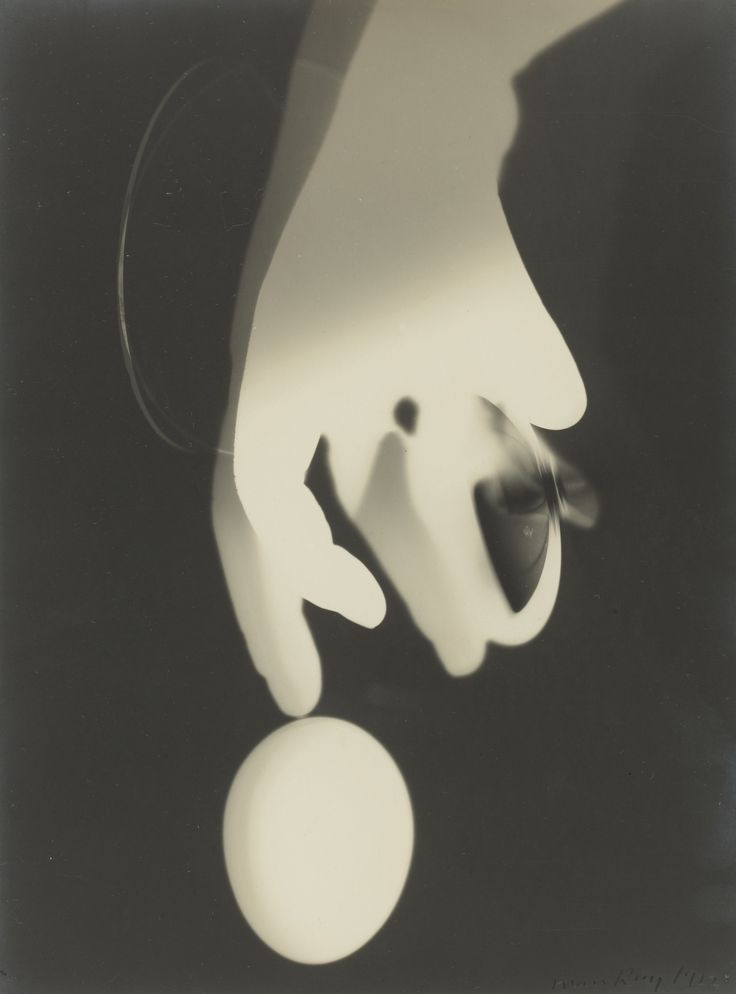

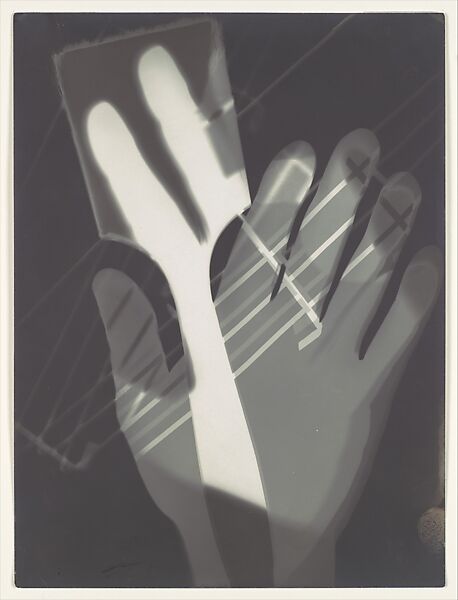

Those artists were doing with photography something very similar to the process of ready-made explained to the world just few years earlier by Marcel Duchamp. They realized that they could do with photography the same ACT OF DISPLACEMENT AND REPLACEMENT in artistic context (that Ducahmp did physically with the Fontaine) by framing it (and making it a 2D piece of paper and hang it on a gallery wall) with photography. That’s why a bunch of avant-gard visual artists literally in the same period experimented with real objects on photographic paper (with no camera):

The power of monumentalization through photography have different examples throughout art history.

Some works by land artists from American Minimalism during the 60s are still linked to the dada and surrealists walks in the outskirts of urbanization and further investigate the SUBLIMATION OF ORDINARY THROUGH ART PRACTICE.

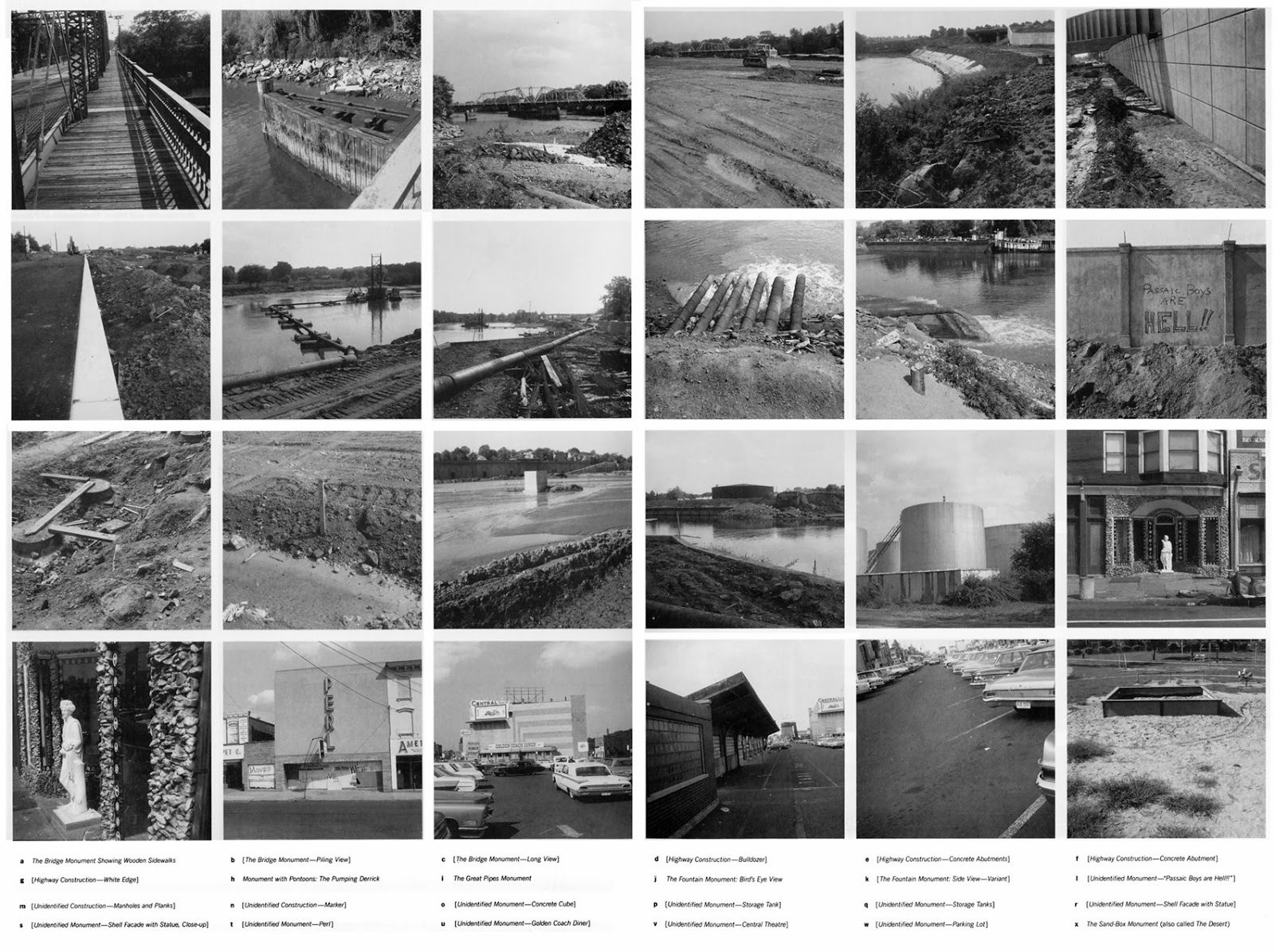

In 1967 Roberth Smithson made a trip between New York and the village of Passaic in New Jersey, where he had grown up, and produced a short textual and visual essay in which he describes the various industrial and suburban relics he encountered during the journey, reconfiguring them into hypothetical monuments of a civilization to come. “A TOUR OF THE MONUMENTS OF PASSAIC, NEW JERSEY” gives us a very clear example of the reconfiguration that artistic (or photographic) practice produces on how we look at a given landscape.

The explicit use of the term “monuments” reveals the intentions of Smithson. What we now recognize as unfortunate or neglected can be a monument. Even something we feel ashamed of can become part of cultural or artistic heritage.

Photography is not Smithson’s main medium, but he uses the camera to decompose reality into samples and items that he “picks” on film in order to turn them into cultural products along with the landscape they form.

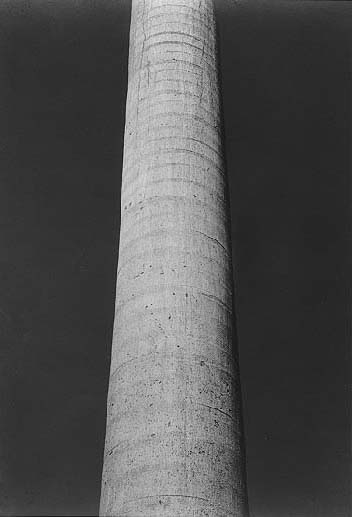

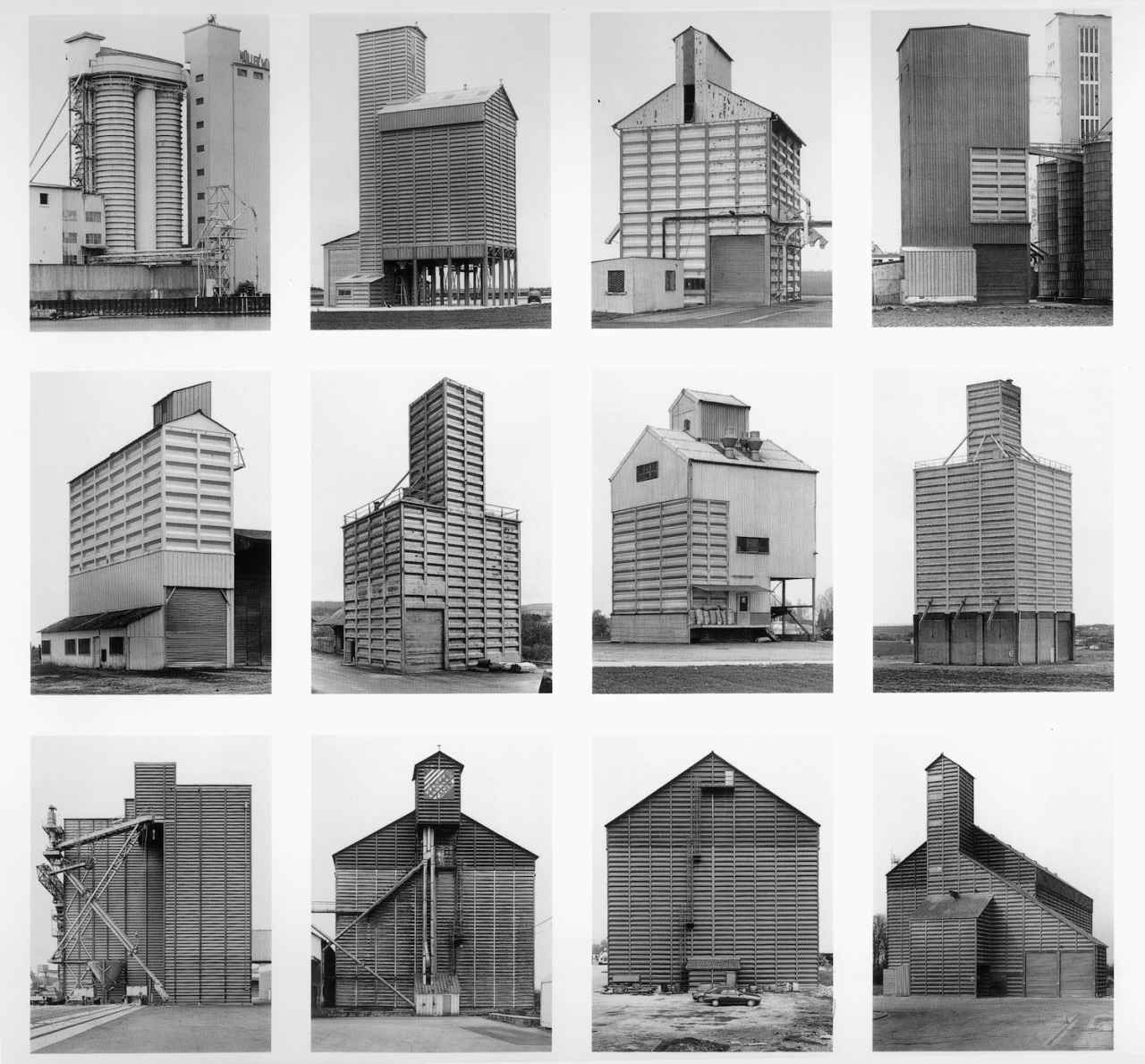

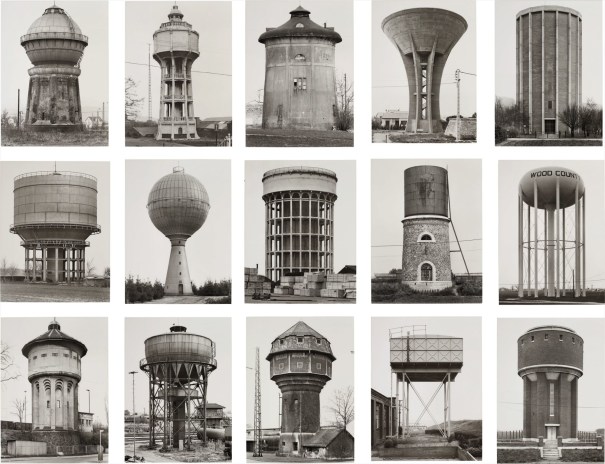

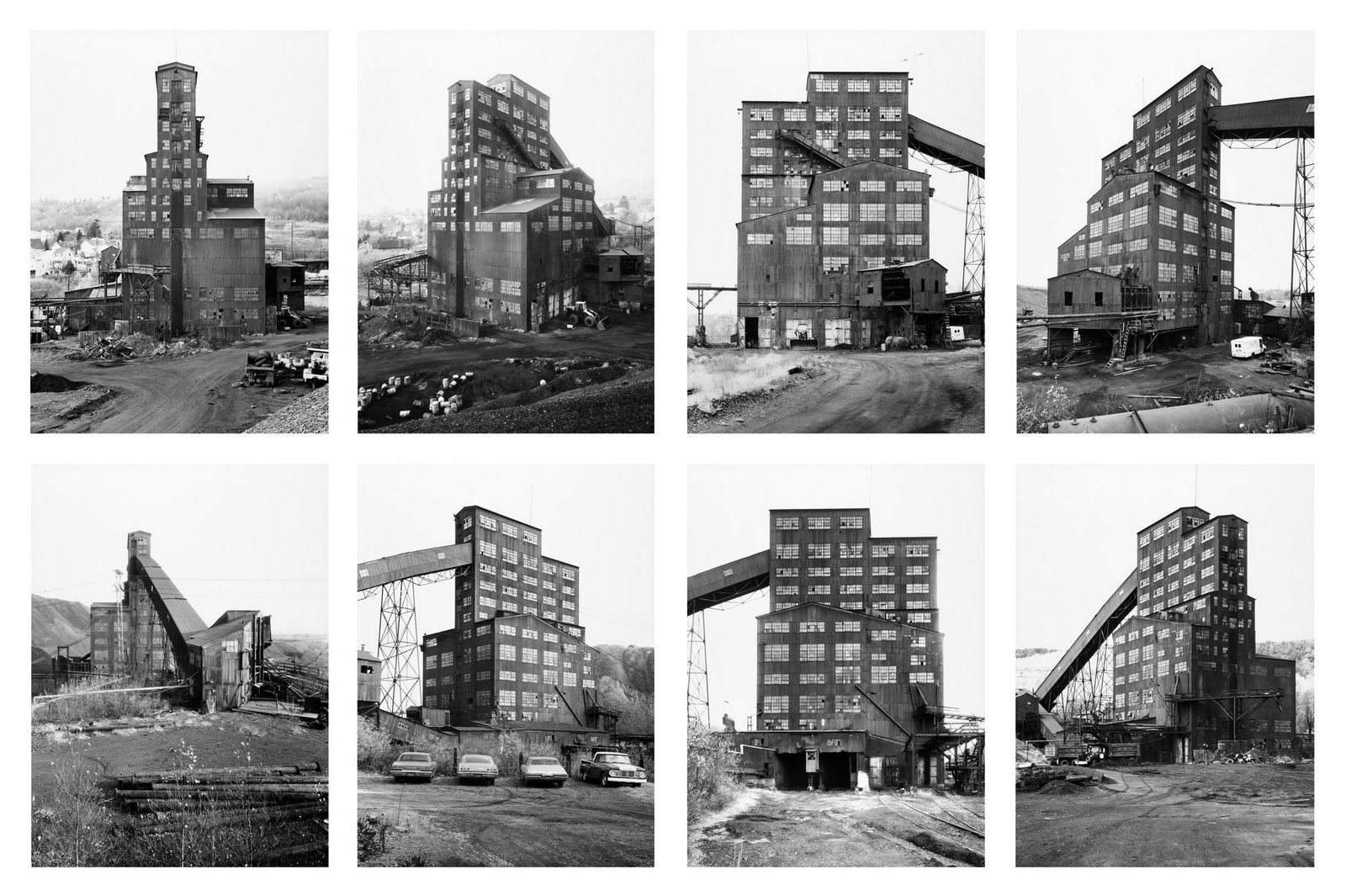

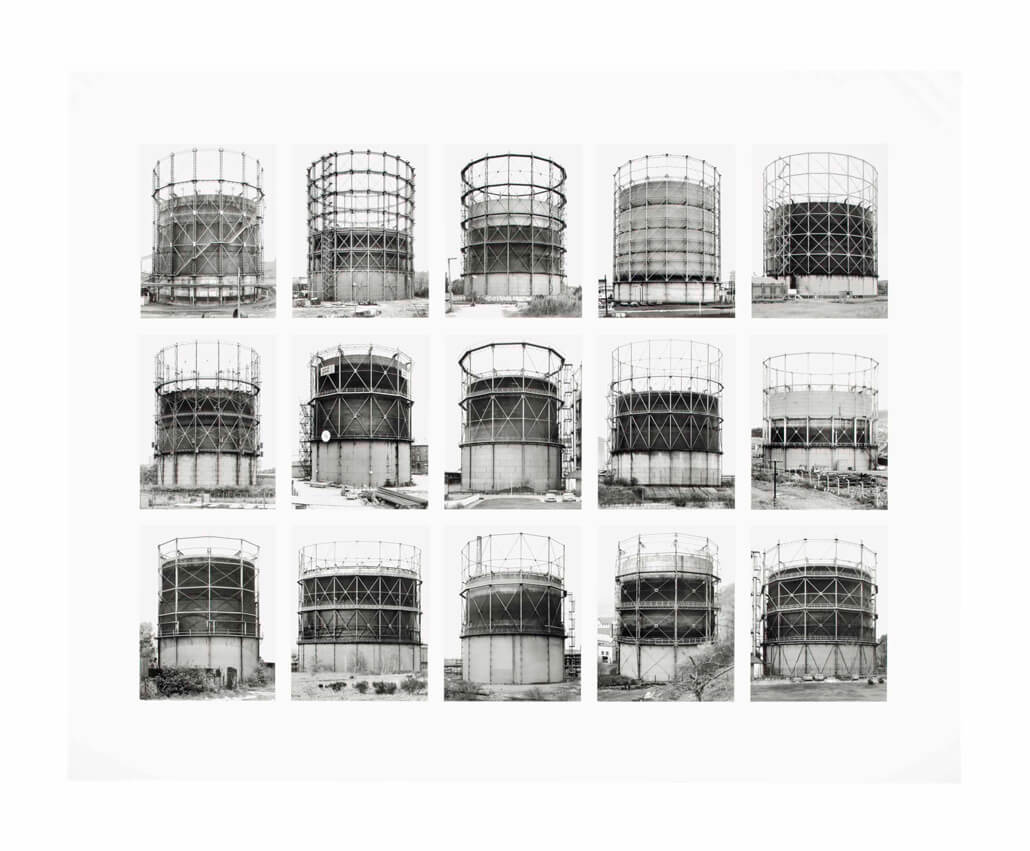

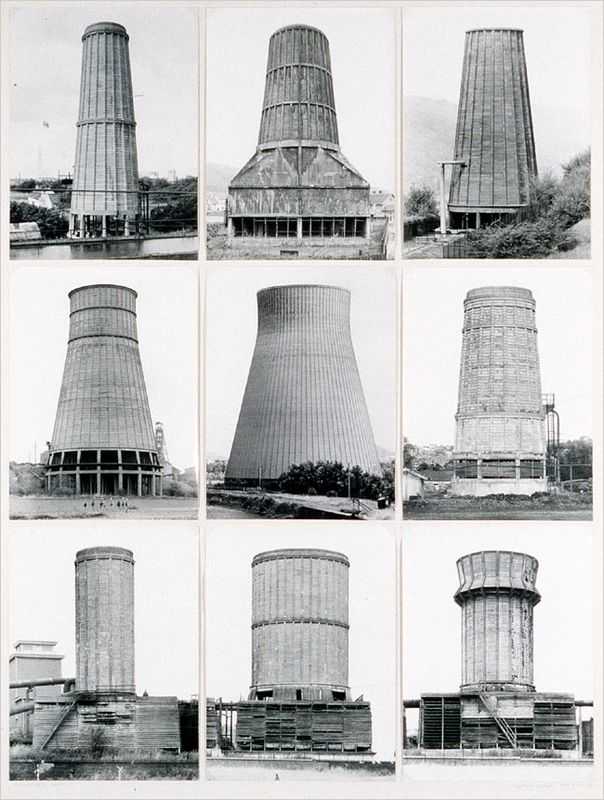

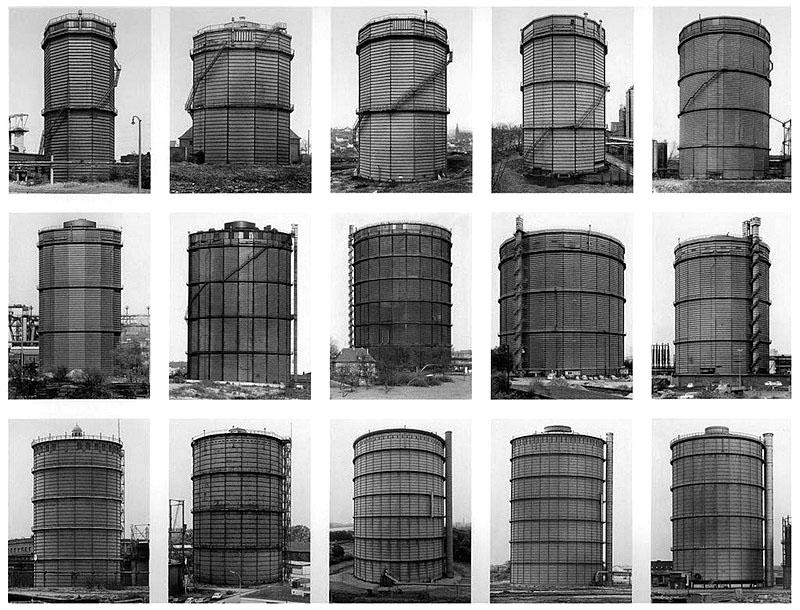

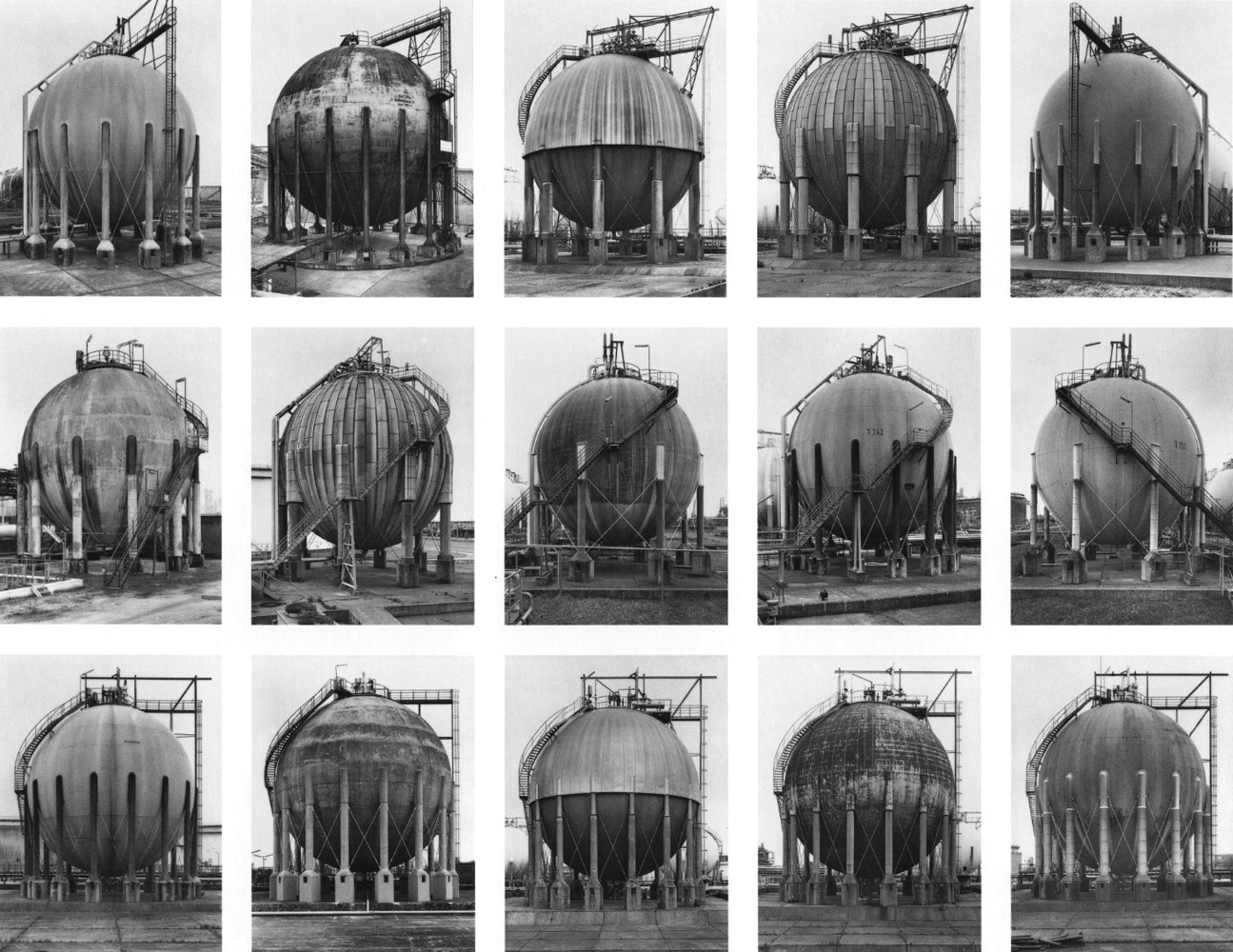

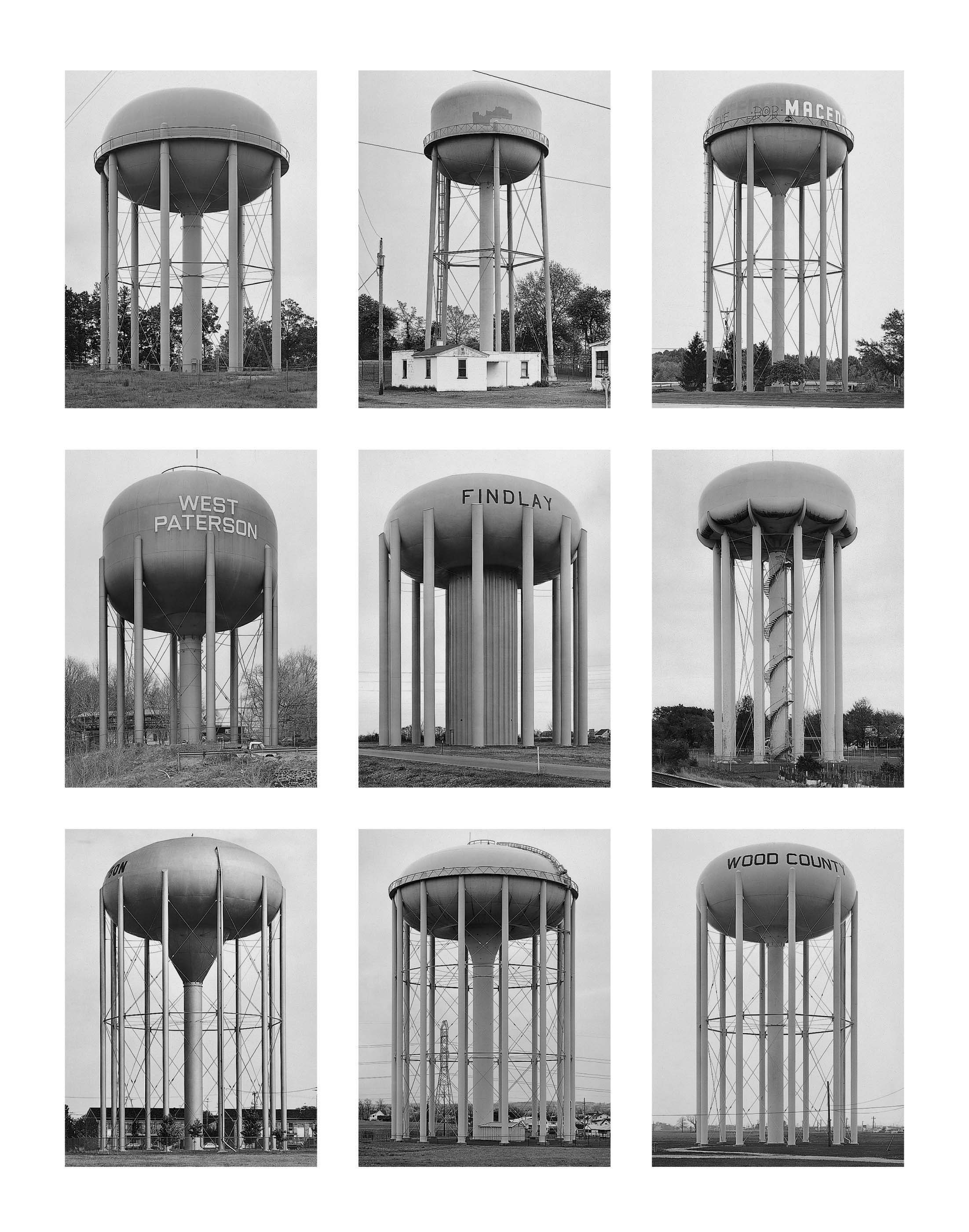

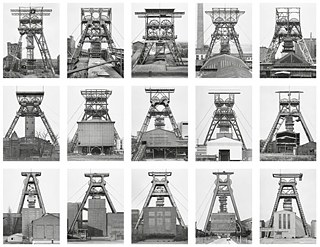

At the same time, the photographers Berndt and Hilla Becher were realizing an encyclopedic research on this subject, photographing hundreds of German industrial structures and cataloguing them by form and pattern. The artists predicted that the era of industrial magnificence was coming to an end and that those buildings would soon become relics of a glorious and failed past. They would become HERITAGE.

By using the term SCULPTURES in the title “Anonyme Skulpture: Eine Typologie Technischer Bauten”, the Bechers explain how the process of formalization that takes place through framing and photographic “take” is absolutely consistent with the concept of readymade: Duchamp materially moves an object from reality to a cultural and artistic context; photography produces a similar shift by leaving the object where it is but making it portable through reproduction and printing.

In fact, in 1990 Becher won the Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale in the category of Sculpture, as if they had transformed industrial structures into sculptures, and had transported them to the Venetian pavilions.

Becher’s work states with no doubt that photographing something turns it into a monument.

Again with Studio Figure we addressed this topic in PLAYGROUND, a series of participatory actions of iconographic reconfiguration of the landscape. It activates the local community in the construction of ephemeral installations in the public space and aims at creating, through the use of photographic medium, a new common and shared iconography of a given landscape.

Trani (BA), Italy

2022)

After a year we went back to the stone platform at the bottom of one of the caves in order to realize further action with a working group of local photographers and artists.

Back to our monument in Malta and to contemporary tourism in general…

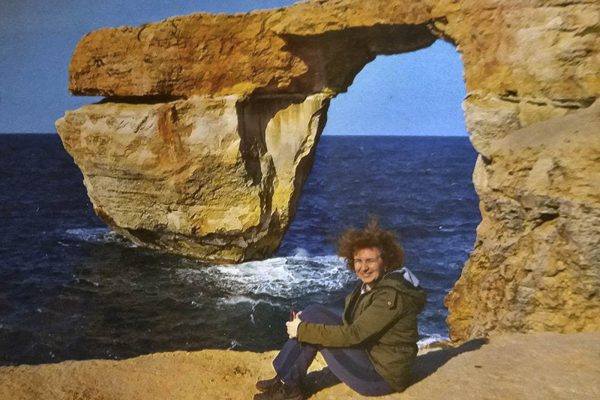

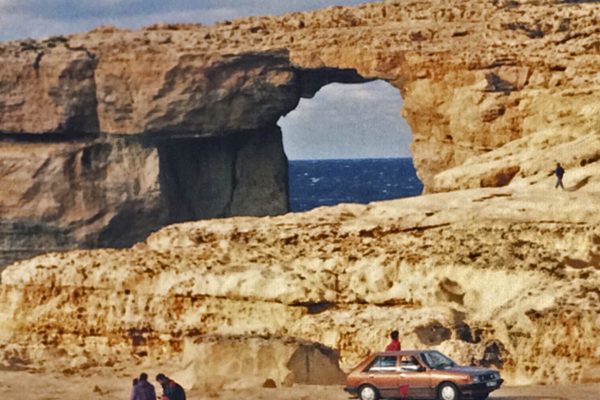

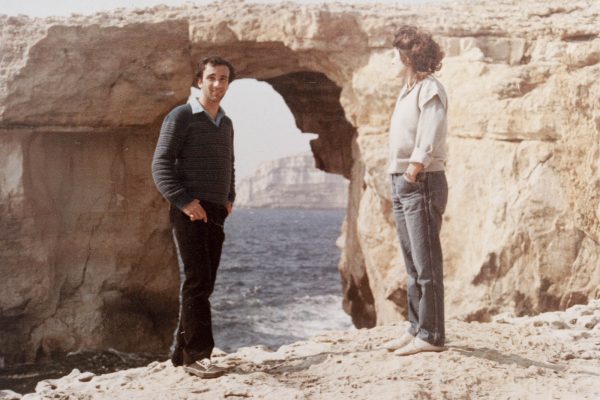

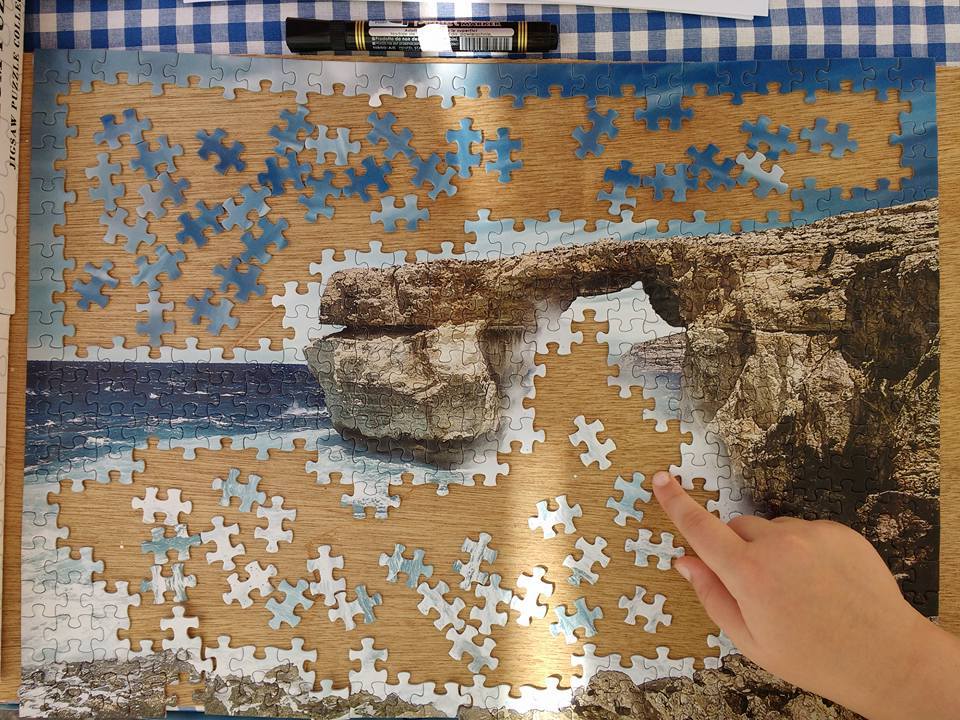

Inhabitants of San Lawrenz, the village where the Azure Window was, realized that the memory of their own landscape and of their beloved natural monument, especially now that it was gone, was represented by an HOMOLOGATED, REPETITIVE AND STANDARDIZED ICONOGRAPHY that was randomly produced by tourists, who photographed it not because they cared but because they wanted to feed their own digital ego by posting the picture of Dwejra on their social media.

I find the desire of the workers and investors in Alexander Gardner photos of the construction of American railways (and in general the desire to be pictured as a “modern man”) very similar to the DESIRE of the tourists to see themselves staged in fancy and popular locations. They both want to represent something better about themselves, by showing they are progressing in life and chasing the dream of progress in middle XIXth century or by showing their success, proven by the fact they are enjoying themselves on holidays on a well-known instagrammable location.

That posers and their looks in the camera, communicate a similar tension wether they are on instagram or in a XIXth century collodion print:

These kind of poses, along with tons of selfies, represented the main visual memory of the azure window at the moment of its collapse. And now that the azure window was gone it was very hard to change this uncontrolled imagery.

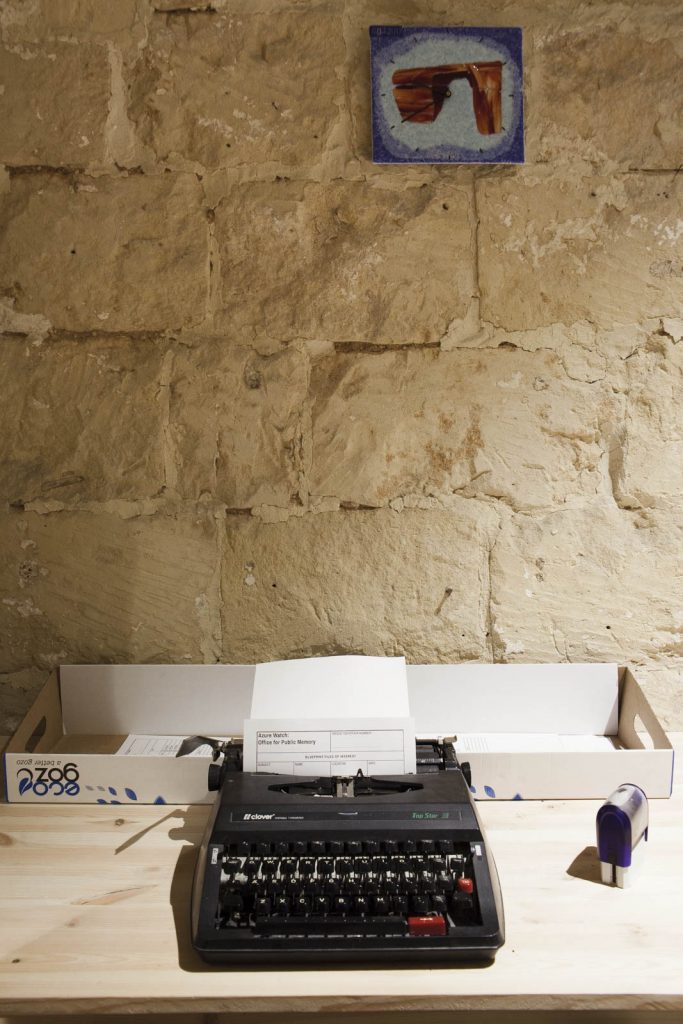

Thanks to an a.i.r. program with Spazju Kreattiv, an art center in Valletta, we decided to start a project exactly about this.

On September 4th 2017 (6 month after the collapse) we issued a sub-call in the form of video-manifesto in order to form a working group of local artists and researchers that wanted to address this theme, also to participate in a debate on the landscape that was being born in Malta following the appointment of Valletta 2018 EU Capital of Culture.

Azure Watch call for action

Edit by Giuseppe Fanizza

That was the main question. of the project:

Is this how the local community wants to remember its beloved “Dwejra” (the Maltese name of the Azure Window)? Is this really the iconography that the inhabitants of Gozo want to preserve forever?

Or, to put it in another way:

is there a chance for local communities in heavy tourism location to control the iconography and imagery of their own landscape? (DETOUR)

The group’s statement, expressed in various press releases, was clear in this regard:

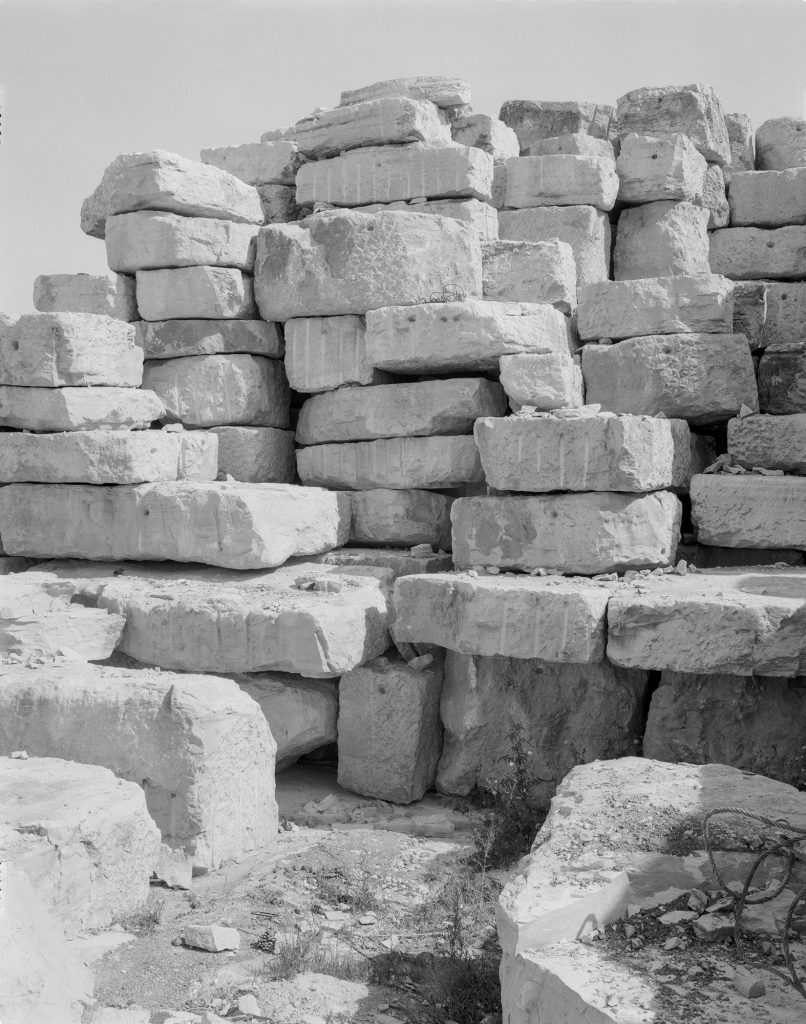

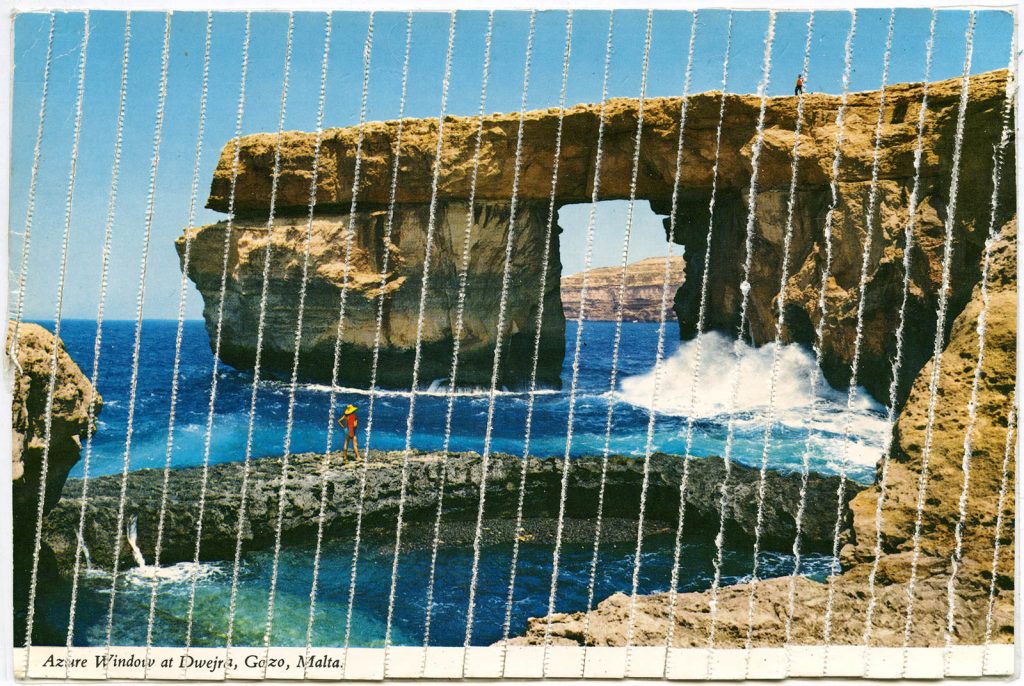

Besides the impact on the environment and on the tourism economy of Gozo, the collapse of the window has equally important consequences on the iconography and the topographic memory of Gozo landscape.

The imagery of the Azure Window available on the internet, as transmitted by the tourists who visited the island, shows a standardised iconography that could become the only future memory of the Gozo landmark. In order to avoid such homologation and loss of identity, a prompt and common action needs to be taken.

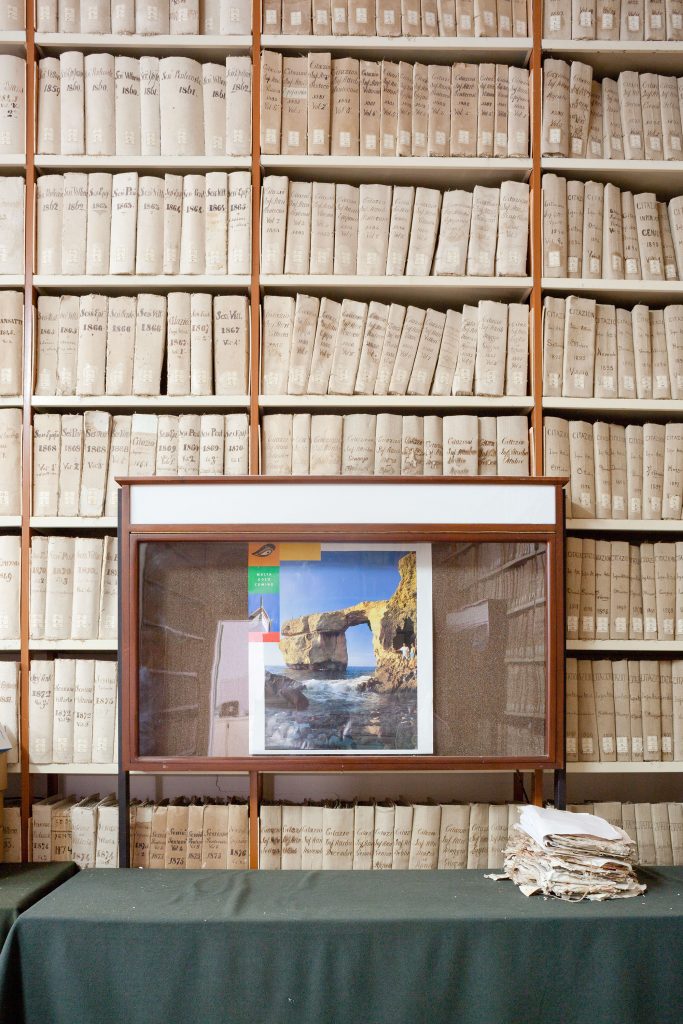

Interior of the National Archive Gozo section. © Azure Watch – Spazju Kreattiv

The objective of the process was to start a collective multimedia archive on the Azure Window and the surrounding landscape, to make it available for consultation and future integration by the Gozitan community.

Azure Watch collected from citizens and local institutions hundreds of photographs, different video contents both original and public domain, interviews, paintings, sculptures, tapestries and other objects, all depicting the Azure Window, which were presented in two exhibitions, the first entitled “Azure Watch” at the tower of Dwejra, a few hundred meters from the place of the collapse, the second “Office for Public Memory”, the following year, in an old mill converted into an independent exhibition space in Valletta.

The image collection is edited by Mary Attard, Andrew Pace, Johannes Buch and Giuseppe Fanizza and includes photos by Mary Attard, Josephen Bailey, Daniela Bertolini, Alda Bugeja, Dorota Gromek, Katarzyna Kryszk, Merga Cordina, Attila Demeter, Yarushka Li, Austin Gragg, Diana Cristalova, Nace Sapundjiev, Alessandro Lai, Andrei Dumitriu, Rich McCor, Ian Holmes, Brian Cassar, Damian Ebejer, Greta Ellul, Sonia Di Vaio, Sandra Barkovic?, Fritz Weinsberg, Marie Calloch, Quynh Pham, Pukar Shakya, DePaseoX, Joe Janman, Yiqun Wang, Campbell Kerr, Ian Holmes, Life Plus Style Fitness, Livia Pye, Bea Kunysz, Ton Garcia, Nick Atkinson, Lino Mifsud, Paula Hubner, Monica Gergely, Lucas Mateo Cardoso, Patty Fryer, Aline Krzisch, Viola Saliasi.

Azure Watch (senza titolo), 2017

Camera by Giuseppe Fanizza e Johannes Buch

Editing by Giuseppe Fanizza

16’28’’

Azure Watch (Appropriation), 2017

Editing by Andrew Pace

24’19’’

The research process was presented in two participative exhibitions, including works from local artists and artesans (please visit Azure Watch Facebook Page), at Dwejra Tower, San Lawrenz, Gozo, from September 30th to October 29th 2017 and at Gabriel Caruana Foundation, Birkirkara, Malta from March 22nd to April 11th.

Editing by Giuseppe Fanizza

1’26”

Appropriation of scenes from “Clash of Titans” (1981).

Music: Renato, “Ma Nichdek Qatt”.

This kind of actions, which was proposed in Malta as an artistic project so with also a defiant provocative purpose, are actually not so uncommon and are really happening in many places in the world where different COMMUNITIES ARE STARTING TO REACT to the commodification and objectification of their landscape and territory.

In October 2019 some American media reported the case of the Joker Stairs, a staircase of Highbridge (in the Bronx), which has become very popular destination for influencers and instagramers because used in the movie “Joker” (2019) as the location of a scene in which the character of the clown villain, bitter enemy of Batman and played by Joaquin Phoenix, performs a macabre and morbid ballet.

https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/31/movies/joker-stairs-bronx.html

Of course this doesn’t happen in the Bronx only.

Notting Hill, London

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-6754933/Hundreds-Instagram-stars-irritating-Notting-Hill-locals-posing-snaps-steps.html

Rue de Cremieux, Paris

https://www.independent.co.uk/travel/news-and-advice/paris-rue-de-cremieux-instagram-residents-gates-social-media-influencers-a8817356.html

It is here that Sontag’s dystopia comes true and evolves, introducing a causal link between photographed reality and empirical reality:

It would not be wrong to speak of people having a compulsion to photograph: to turn experience itself into a way of seeing. Ultimately, having an experience becomes identical with taking a photograph of it, and participating in a public event comes more and more to be equivalent to looking at it in photographed form … Today everything exists to end in a photograph. (Susan Sontag, On Photography, 1977)

We decide to live an experience because it is very photographed and in order to be able to re-photograph it, in a cyclical, infinite coincidence between the reason and objective of our travels.

The hyper-production of iconography provokes even firmer reactions when the object or landscape photographed are linked to particularly dramatic facts. Following the success of the award-winning series “Chernobyl” (HBO, 2019), tourism in Pripyat, Ukraine, in the Chernobyl Exclusion Zone, had a sudden surge, as well as the amount of images posted on social media by visitors.

https://www.thesun.co.uk/news/9276402/chernobyl-instagram-influencer-selfies-nuclear-zone/

Very similar is the case of the Auschwitz Memorial Museum, which in March 2019 had to remind its audience that it is a place where “over 1 million people were killed”.

You can feel something like a CIRCLE OF SHAME going on here:

a place we’re ashamed of at a time, becomes heritage and we re-open it as a museum, we realize that photos posted on social media by the visitors are a powerful campaign to attract other visitors but right away we are ashamed for their behavior…

https://www.demilked.com/holocaust-memorial-selfies-yolocaust-shahak-shapira/

I realized another project about this topic during Matera 2019 EU Capital of Culture.

The case of Matera is paradigmatic in relation to the theme of iconography: first the mark of “national shame” in Italy in the 50s, then the progressive abandonment of the Sassi, then the inclusion in the UNESCO list of World Heritage (1993) which, on the other hand, did not mean an immediate redemption of that landscape: the forty-year-olds of Matera today remember how, during their adolescence, the Sassi were still forbidden, dangerous, poorly frequented.

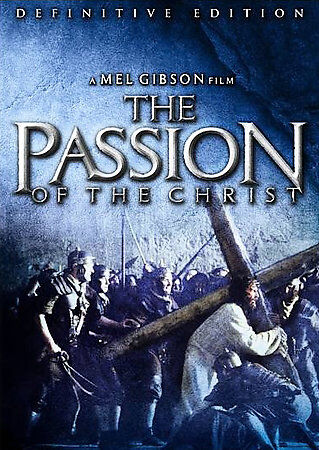

In fact, in the complicated process of redemption of Matera’s imagination, the most important step, perhaps more than in UNESCO recognition, is the choice of the city as the location of the film The Passion of the Christ by Mel Gibson (2004). According to many citizens and tour operators is from then on that Matera becomes a destination for visitors and international tourists, evidently interested in re-entering the picturesque scenery of the gospel.

BRANDING LANDSCAPE

“COMITATO PANORAMA MATERA project mobilizes a group of people working in Matera area in a process of metaphorical re-appropriation of the iconography of the landscape, in contrast with the stereotyped image generated by tourists and visitors to Matera 2019.

The action is part of a series of operations that increasingly involve groups of citizens, artists and even public administrations who oppose tourist colonization and the resulting iconographic over-production.

Symbolically launched in the year of the European Capital of Culture, COMITATO PANORAMA MATERA addresses these issues from the point of view of the shared and mediatized photographic image, developing a long-term strategy that, through heterogeneous practices and languages, covers the public space, the media and the narrower sphere of contemporary art, adopting a political perspective that is both real and paradoxical.”

(Excerpt of the text “COMITATO PANORAMA MATERA. Un processo di riappropriazione iconografica del paesaggio di Matera” by curator Matteo Balduzzi, as published in PADIGLIONI INVISIBILI, Mimesis/Resilienze, 2020.)

A promo video was launched on November 4th 2019 as an awareness campaign against the visual spoil of the landscape, promoting a respectful photography practice, taking care of the ecology of the iconosphere of Matera.

An exhibition at Fondazione SoutHeritage (November 15th, 2019 – January 20th, 2020) presented the results of different activities promoted by COMITATO PANORAMA MATERA:

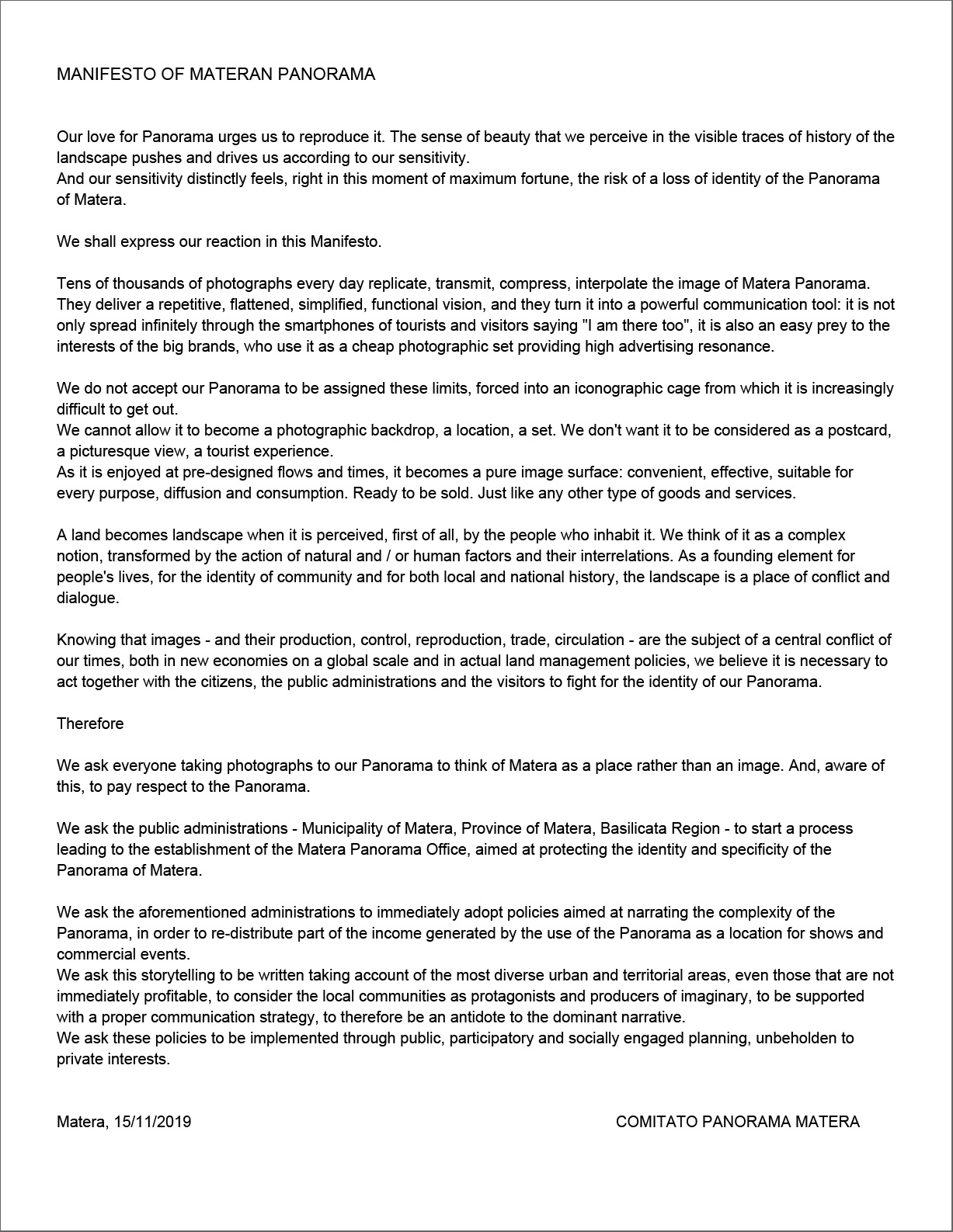

A “Manifesto of Materan Panorama” was written as the outcome of a series of meetings involving people and associations, including ordinary citizens, journalists, local photographers and tour guides, engaged in investigating and describing the territory.

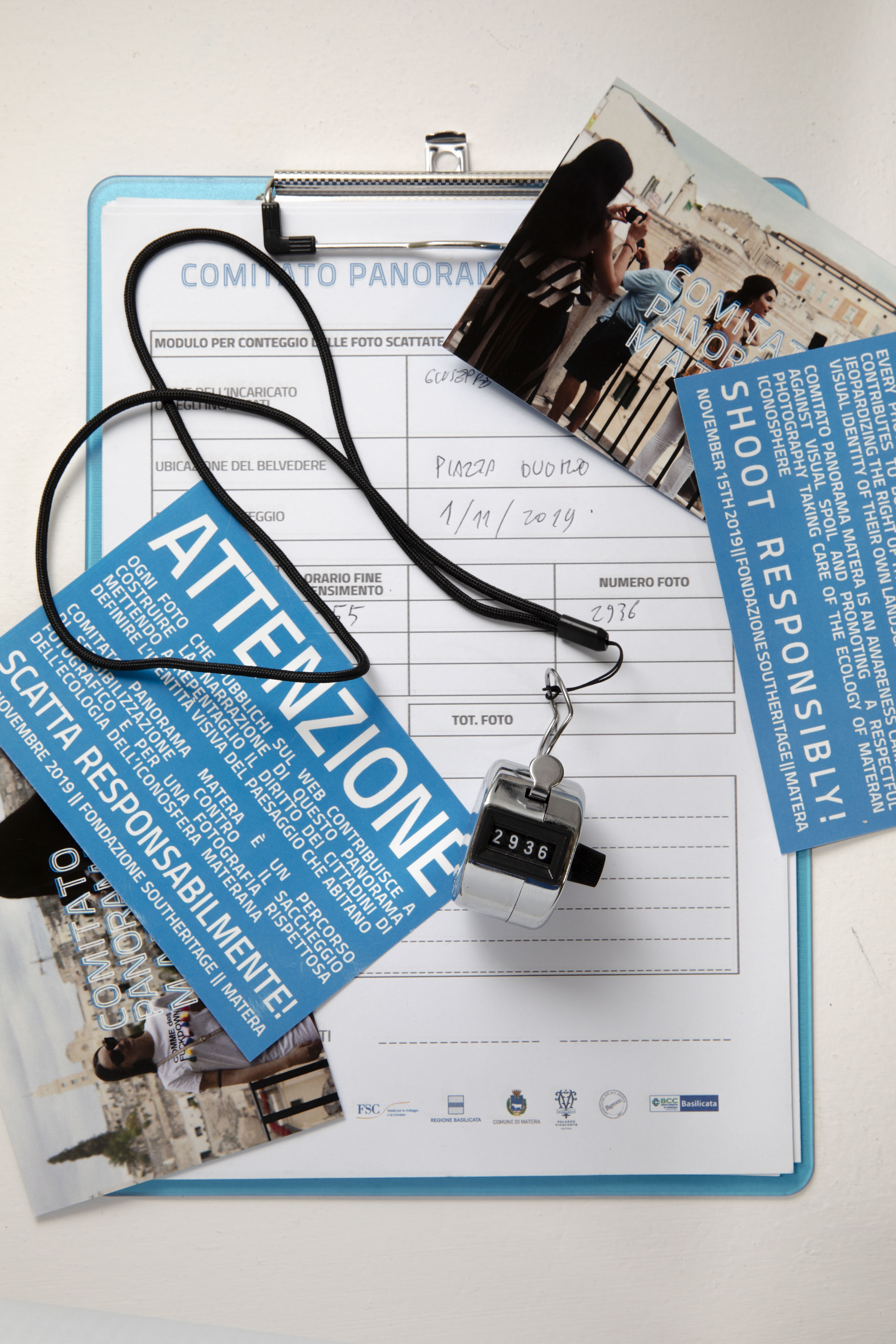

A flash-mob was performed in five famous belvederes in the city, as a sample statistical measurement of the production of photographic images serving as a trigger for a debate about the iconography of the landscape and its abuse. The 24,532 photographs taken over a period of 6 hours on November 3rd 2019 were counted by volunteers from Matera 2019.

A draft re-collection of images from the personal archives of Matera inhabitants and culltural associations, was displayed at the exhibition as a first sample of a potential ironic definition of criteria and guidelines for “native” Materan photography.

In all this cases we can clearly see a dog chasing its tail system: the high number of photographs taken in a given place acts as a powerful marker for that place to become a photo-opportunity. This is demonstrated by some tourist operators in Matera, interviewed by the Committee in the preparatory sessions of the Manifesto, when they explain how tourists ask more and more expressly to modify the tours proposed to them to include some PHOTO STOPS in the places from which they take some of the most popular and instagrammable views of Matera. Or even to plan the tour based precisely on these places, together with those already mediatized by the films shot in Matera (and both often coincide).

It seems that the contemporary tourist does not want, once back home, to show his wonderful discoveries, nor to prove to have been in a place that no one had ever seen (which was the greatest achievement of the proto-tourist of the eighteenth-nineteenth century, inflamed by the modernist inspiration of discovery as a source of progress). On the contrary, he wants to tell he’s (also) been in the most “photographed” places and to prove it with his photographs of the same place.

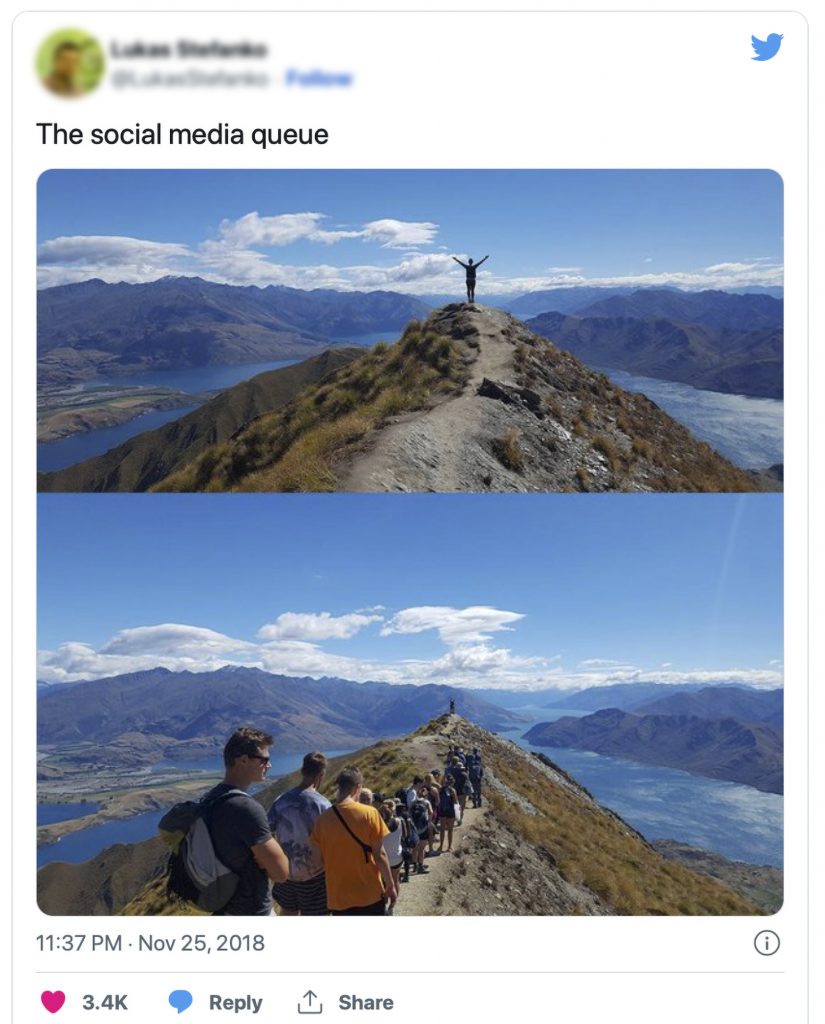

The dimension of this phenomenon is such that we start to find some reaction even at an institutional level. Following complaints posted on social media by some tourists visiting Roys Peak on Lake Wanaka in New Zealand, who reported long queues of other tourists waiting to take a very popular photo on the same social media, the national tourist agency Tourism NZ, has published a tourist information campaign that openly criticizes the tourist behavior of traveling according to the trends of social media (“travelling under the social influence” in the original message). In a series of short videos, a well-known New Zealand comedian impersonates an agent of S.O.S. – Social Observation Squad that chases and “stops” tourists intent on repeating poses on social media magazines, inviting them to leave the recommended routes online and to do, and “share online, something new”.