Photography lessons

IndEX

Lesson 1 – Photography techniques – The machine

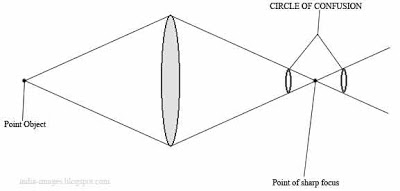

Types of camera – Reflex system – The pentaprism – The Pinhole and then inverted image – The large format camera – Lens and focal length – Focus and the circles of confusion.

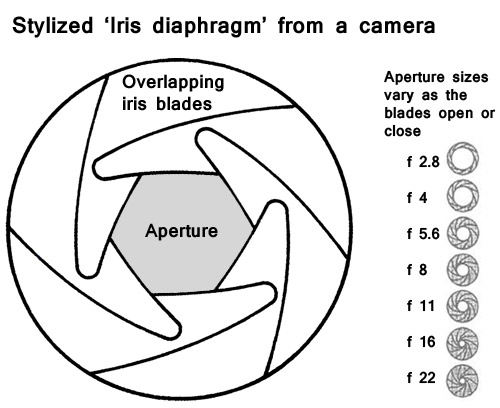

Lesson 2 – Photography techniques – Diaphragm and shutter speed

Long shutter speed – The representation of time – Flashlight and slow shutter – light painting – Diaphragm and depth of field – High depth of field in landscape photography – Low Depth of field in portrait photography

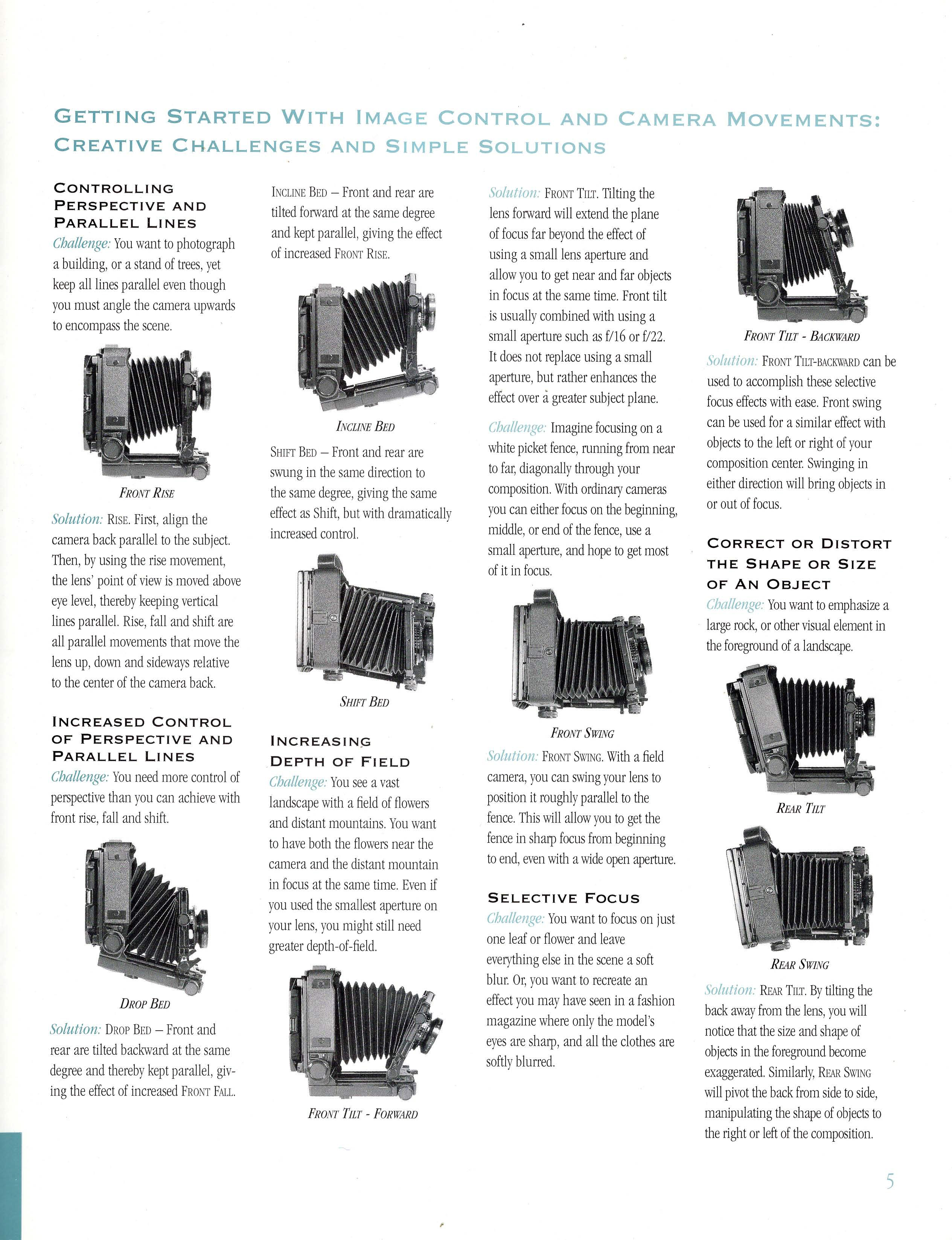

Lesson 3 – Photography techniques – Movements of planes. Shift and perspective correction – Scheimpflug rule

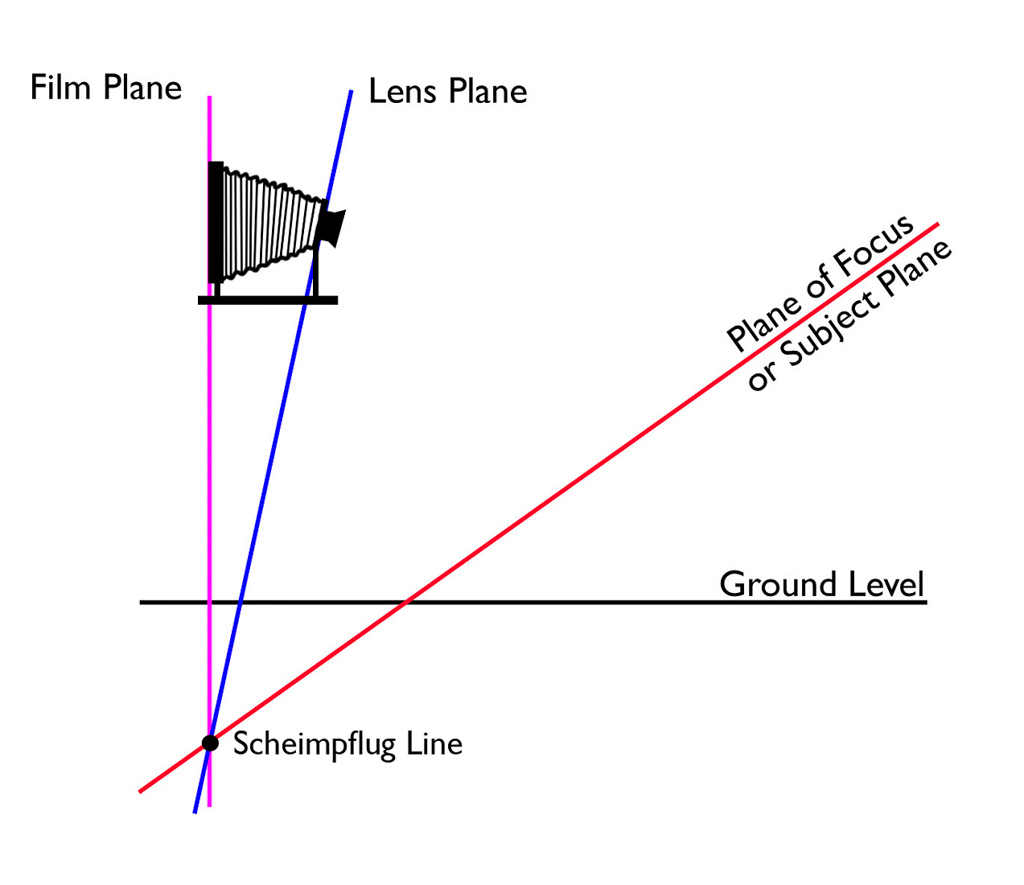

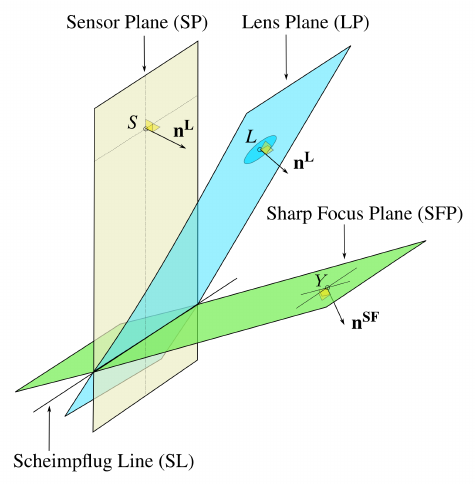

The relations between the plane of the lens, the plane of the film (or sensor) and the plane of the subject – Rise, fall, slide. Tilt – Scheimpflug – “Creative” use of tilting.

Lesson 4 – History of Photography – The birth of the medium

The Origins of framinga – Leon Battista Alberti – Camera Obscura – Fixing the images of the camera obscura: The inventore – Niepce e Daguerre. Talbot – The nationalisation of the invention of photography.

Lesson 5 (+1) – History of Photography – first uses

Excursions Daguerriennes – Daguerrotypic portraiture – Calotype – The album photographique of Blanquart-Evrard. Maxime Du Campe – Collodium – La mision eliographique – La carte de visite – Nadar – First artistic applications – War, exploration, progress, Empire – Stopping the movements.

Lesson 6 & 7 – Photography techniques – The developing process of the negative film

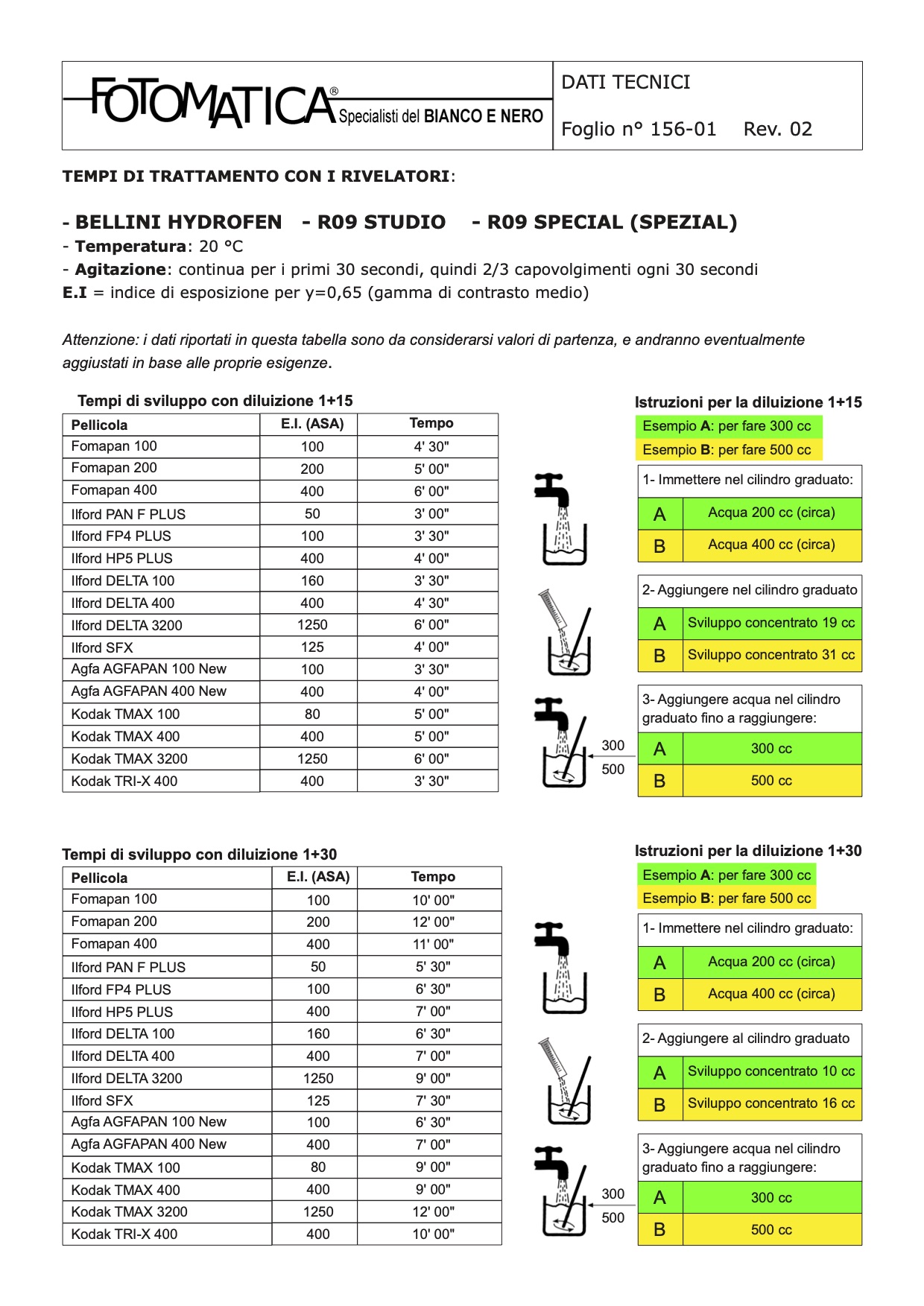

A collection of developing charts from the most used brands of b&w film and corresponding developing chemicals.

Lesson 8, 9 & 10 – Photography techniques – Media theatre – Digital photography and lighting

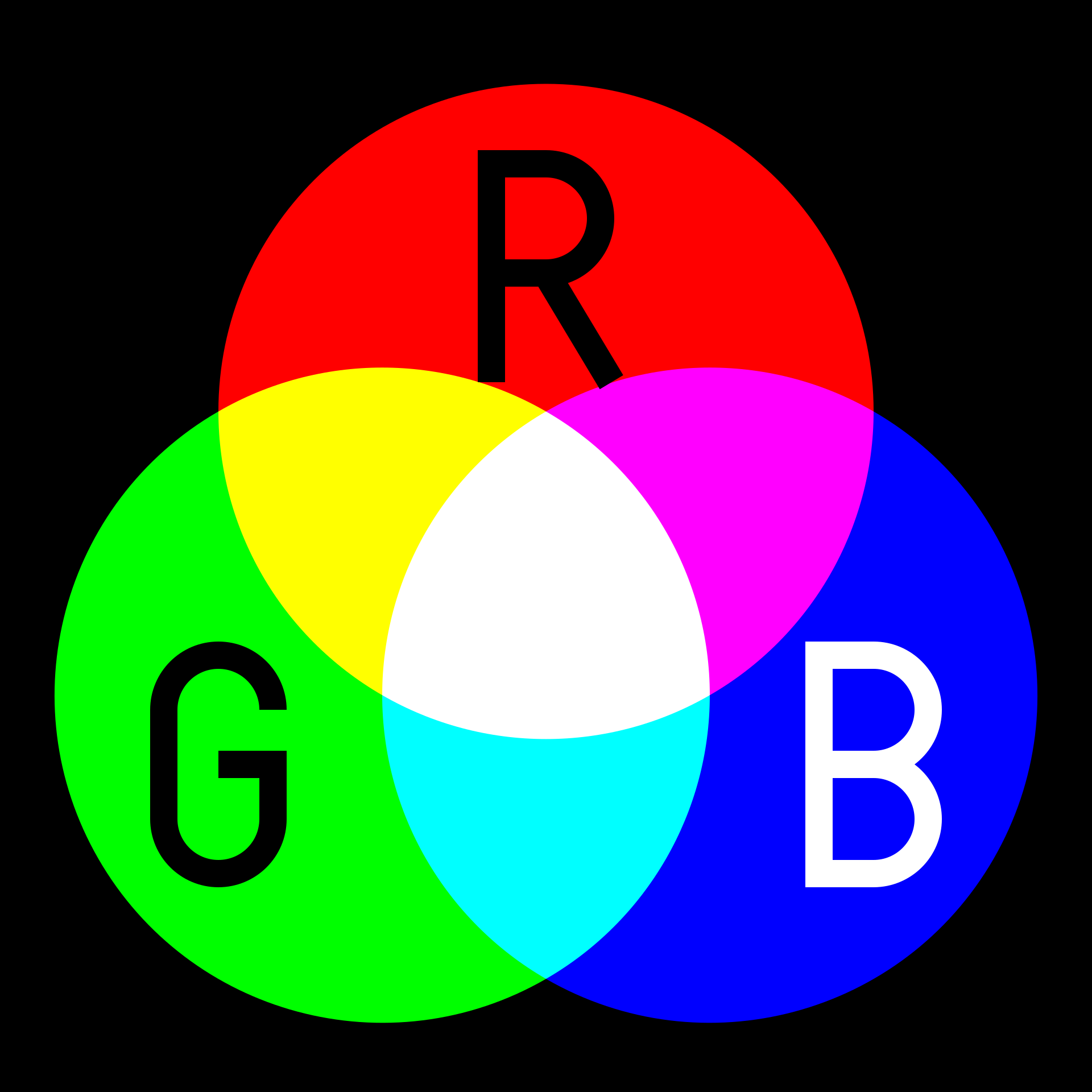

Birth of digital photography – How the sensor works – RGB – origins of color – “Post-photography”

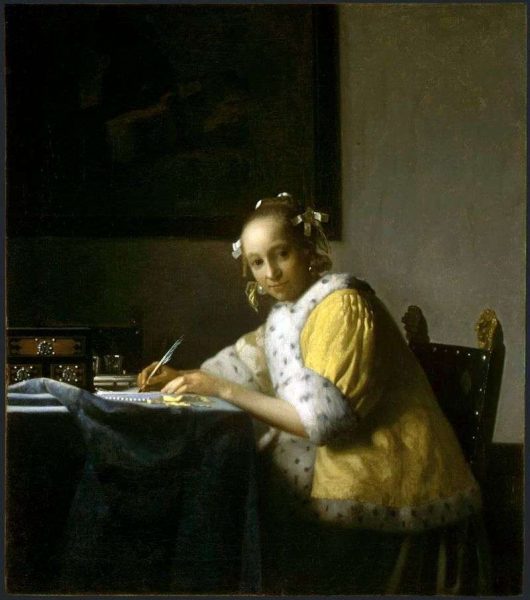

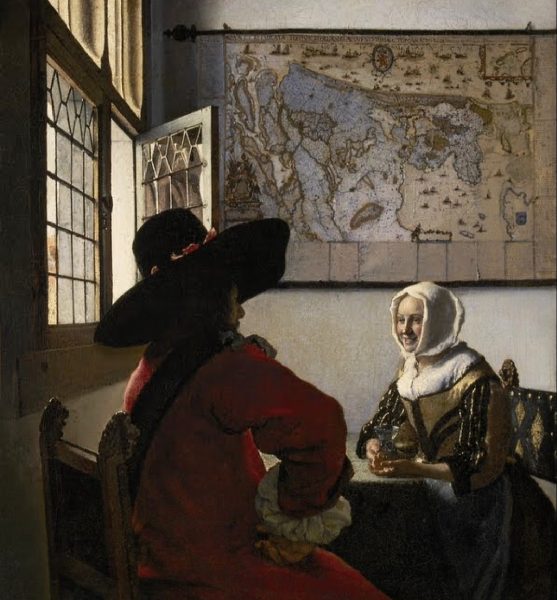

Exercises with the photographic reproduction of a work of art. Reproduction of paintings and statues.

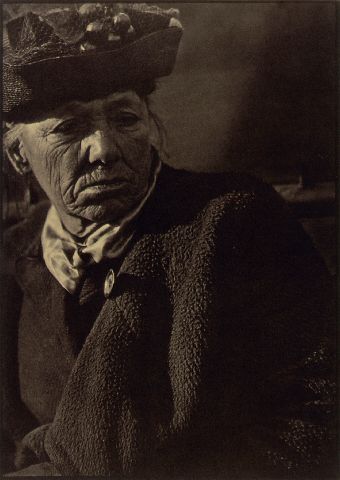

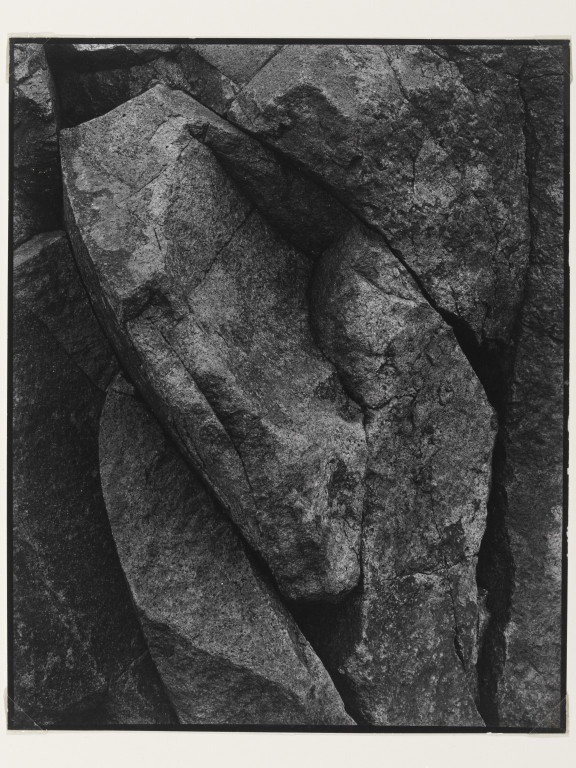

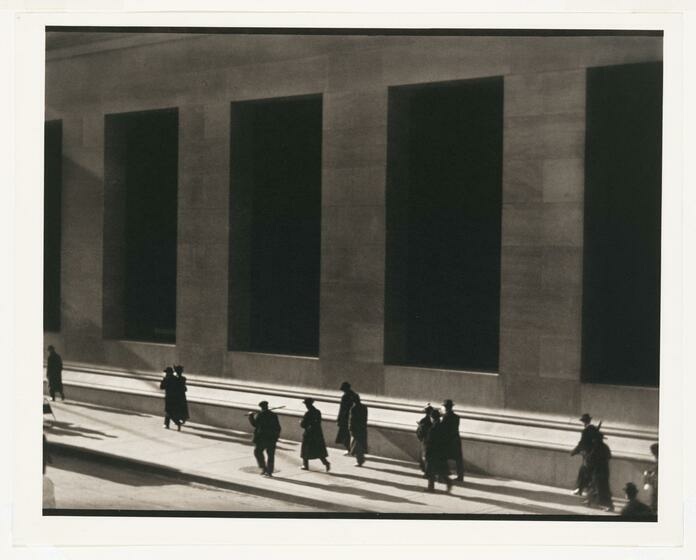

Lesson 11 – History of Photography – Art or not? Documental photography – Public campaigns

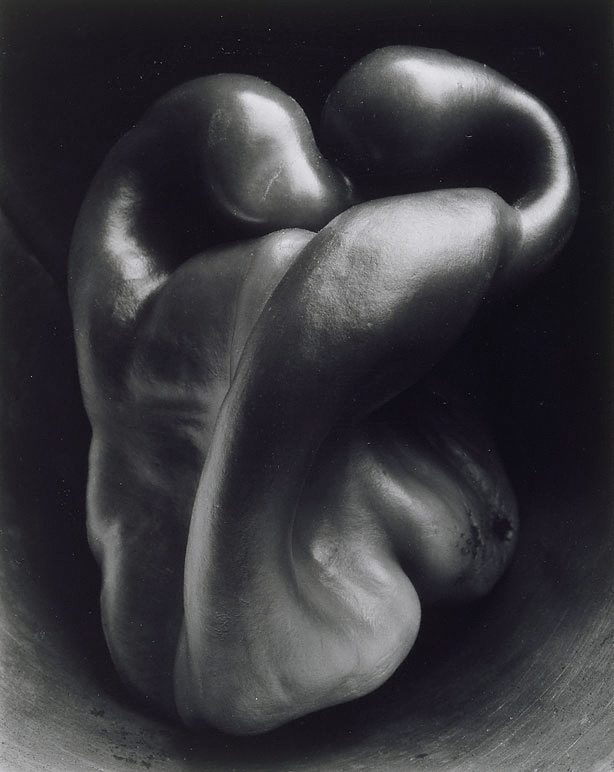

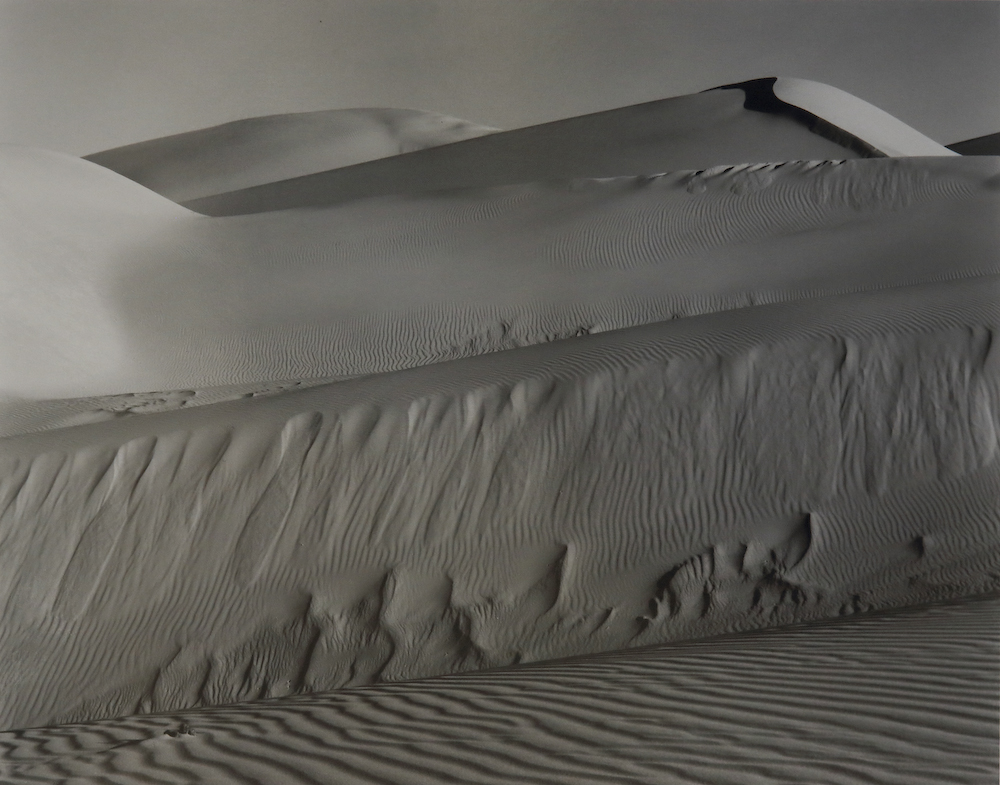

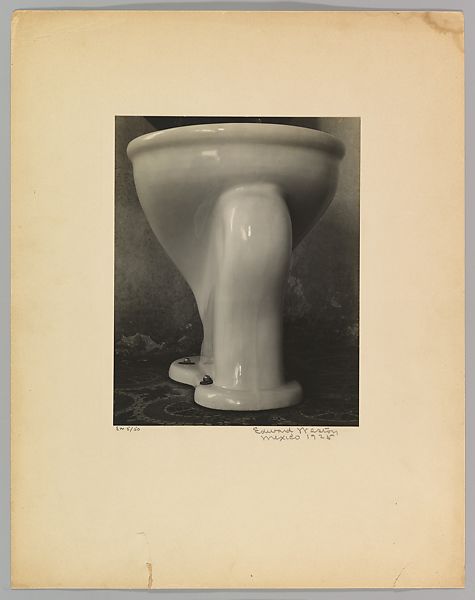

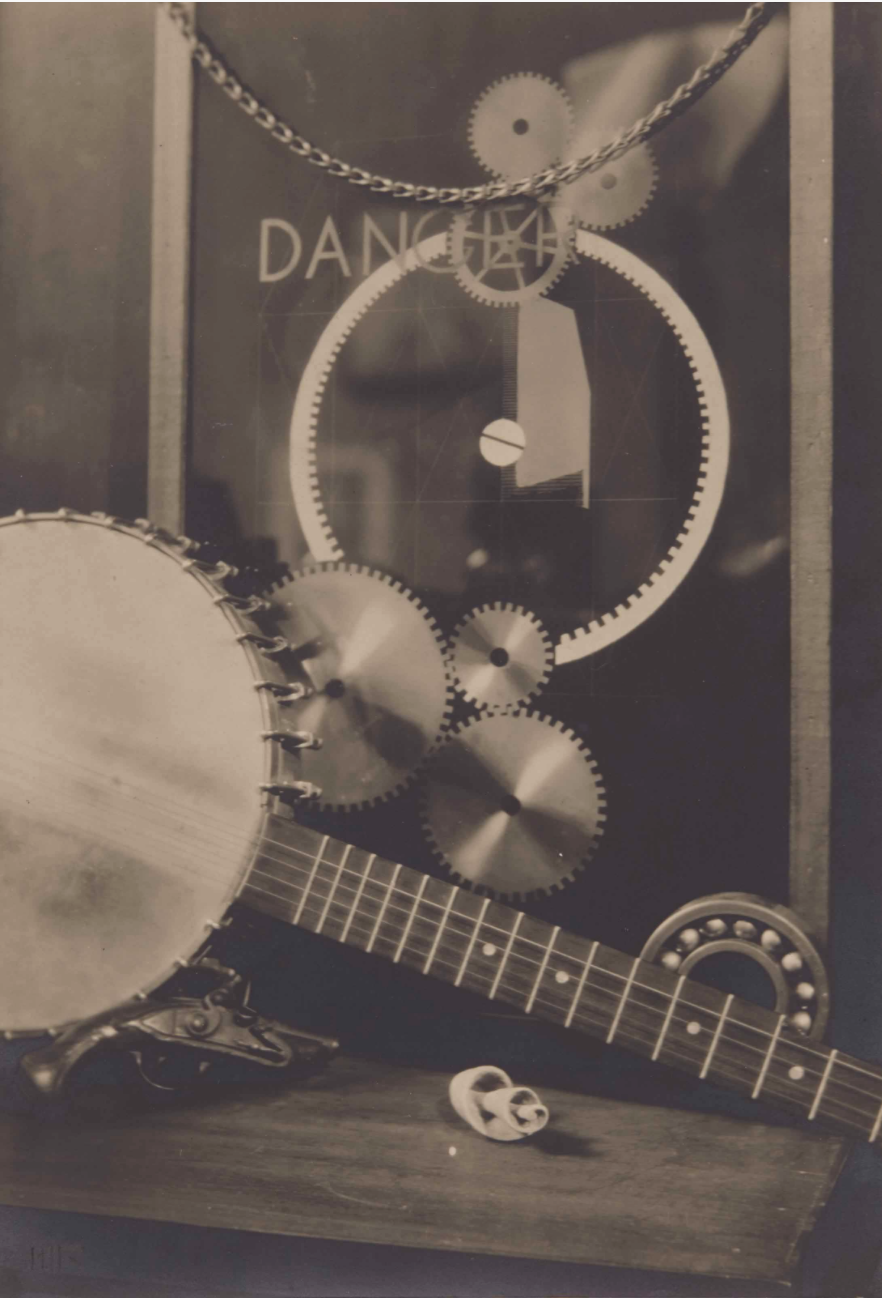

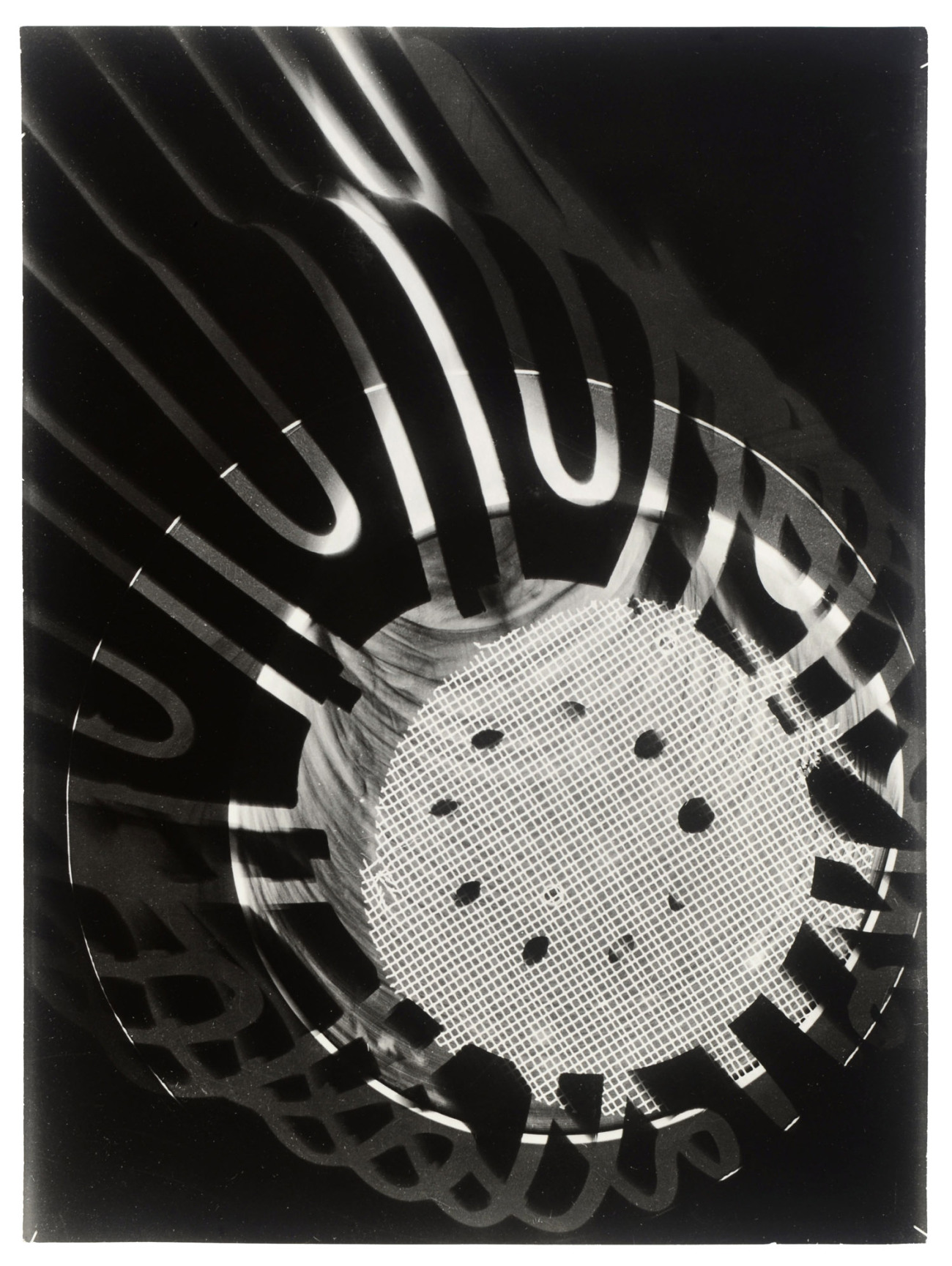

Art or not? – Linked ring, Camera notes, Photo Secession, Camera Work – Pictorialism -Straight photography – Avantgards – Social photography – Documental photography – Public campaigns.

Lesson 12, 13, 14 , 15 – Photography techniques – Photographic analogic print. Designing and development of a personal project

Aggiungere le tabelle con diluizioni, tempi, tecniche di stampa

Lesson 1 – Technique – The machine

35mm – medium format – large format field camera – polaroid – point n shot – digital – reflex – mirrorless – compact camera – Il diaframma e l’apertura – L’otturatore e il tempo di esposizione –

Negative format. 35 – medium – large

Reflex System

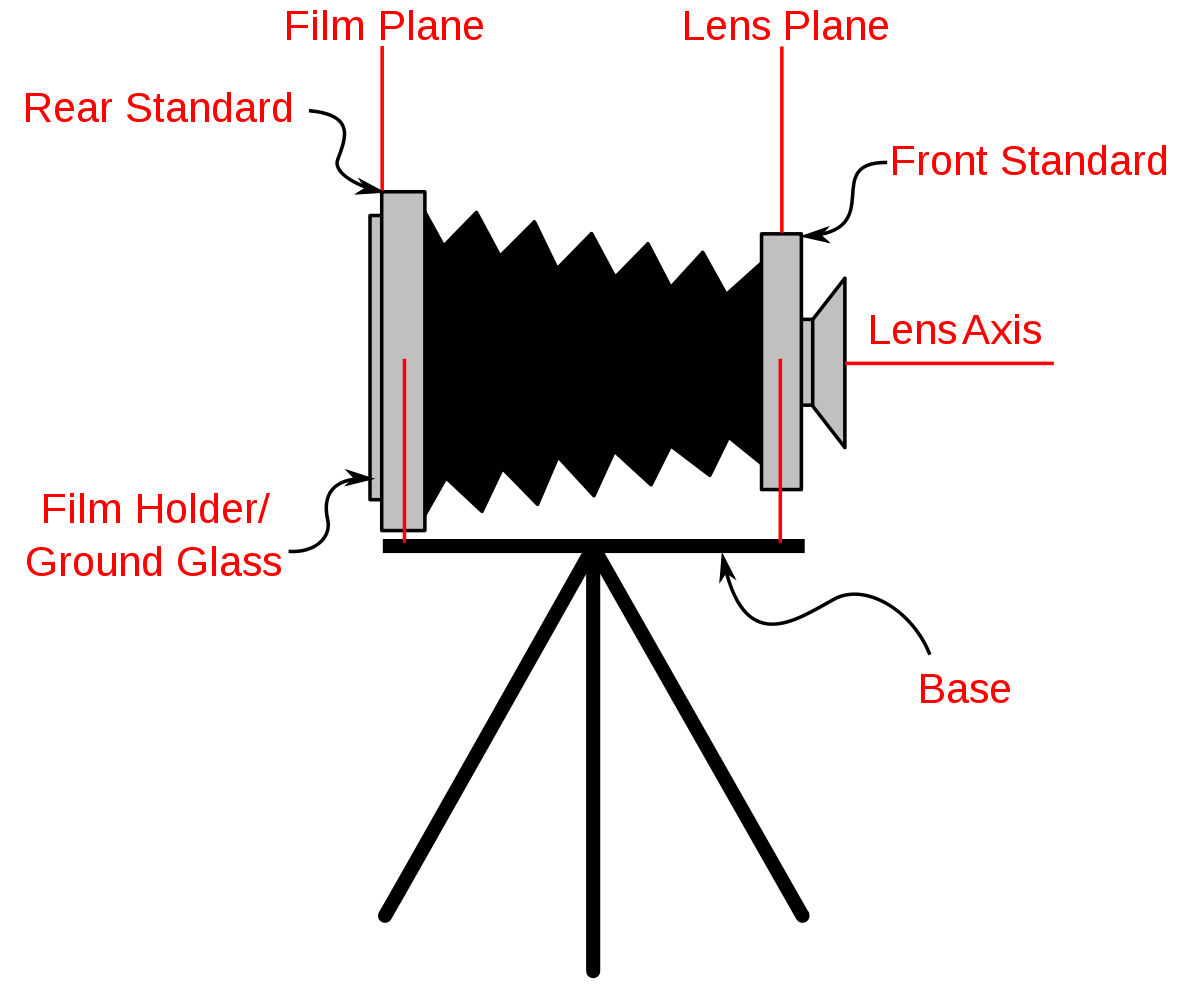

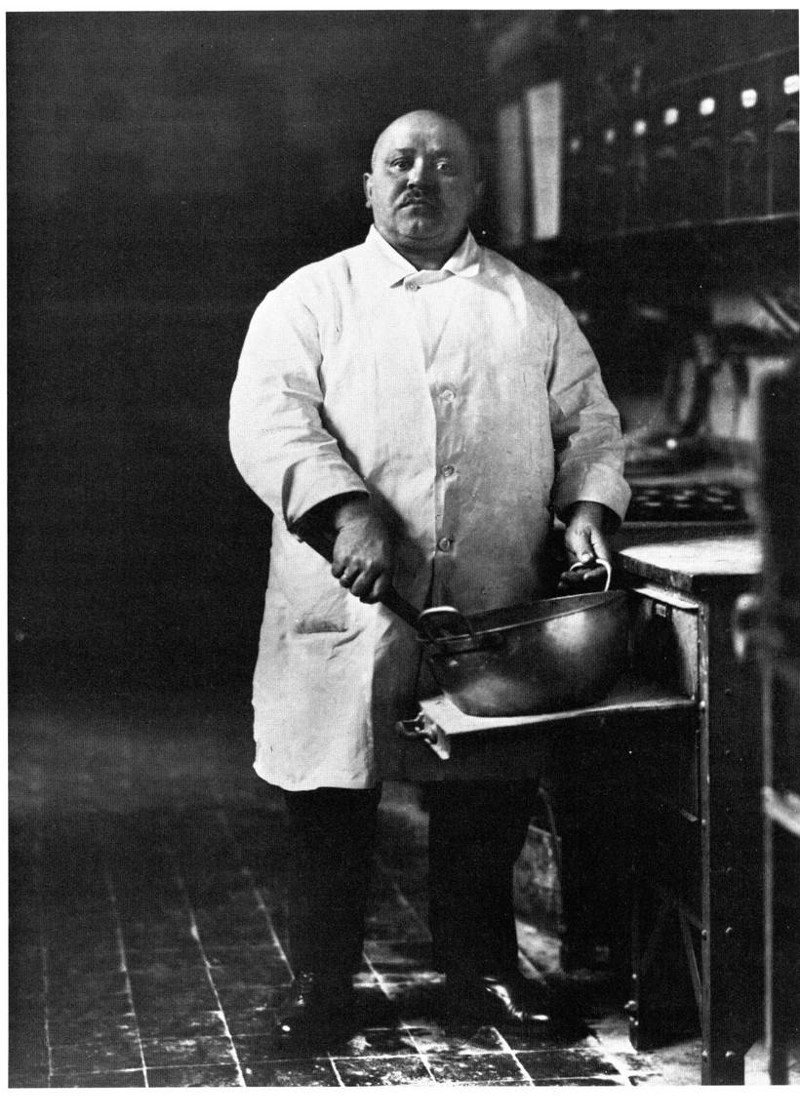

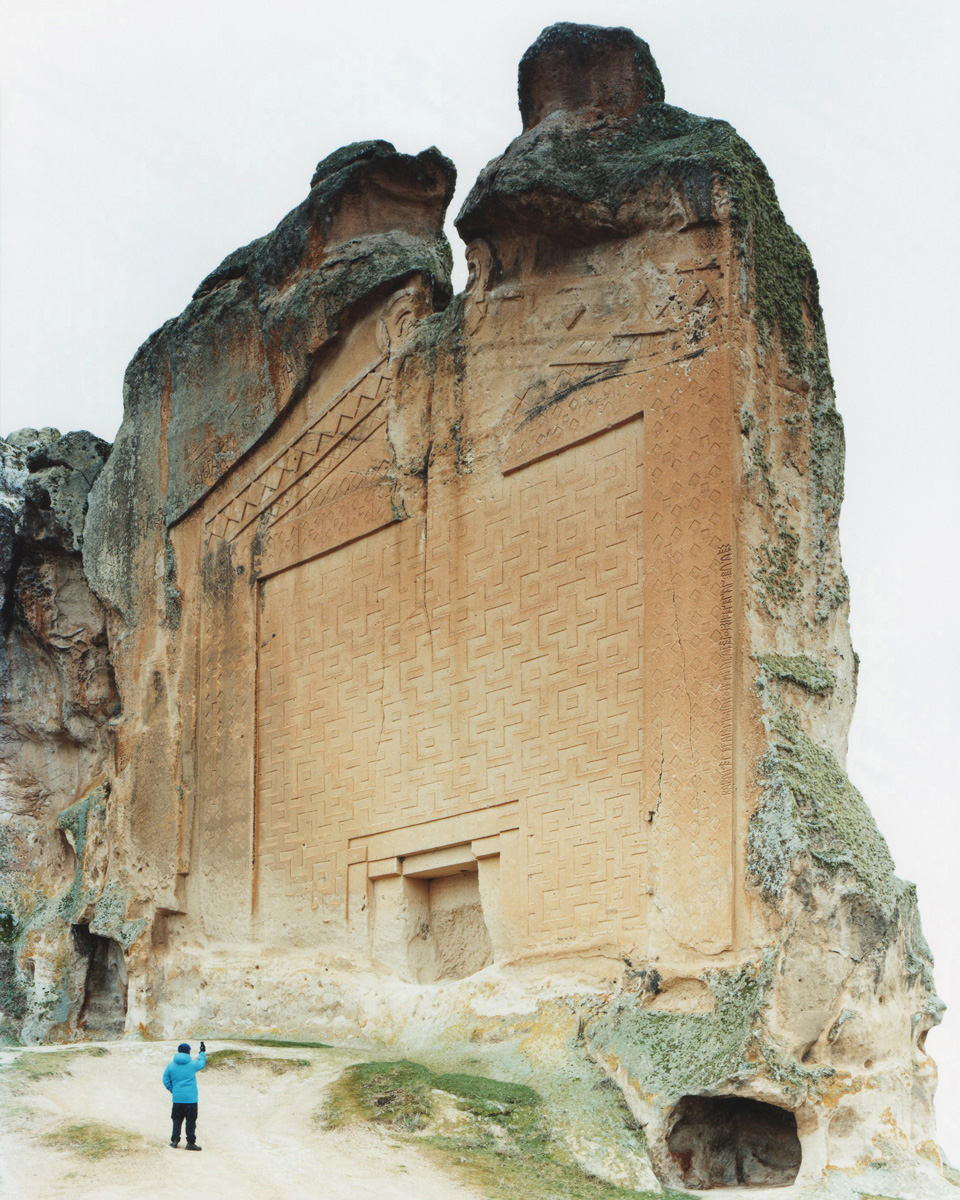

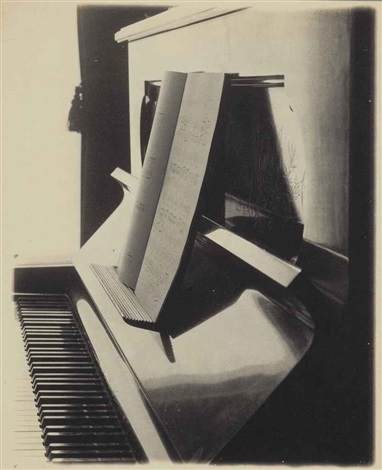

Field Camera

Lens

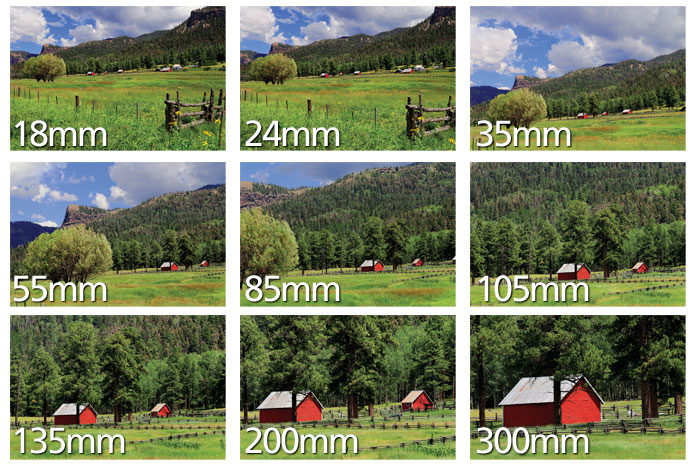

Focal lenght

It measures the distance, in mm, between the optical centre of the lens and the camera’s sensor (or film plane). It is determined with the camera focused to infinity. Lenses are named by their focal length, and you can find this information on the barrel of the lens. For example, a 50 mm lens has a focal length of 50 mm.

Fixed focal length lenses / zoom lenses

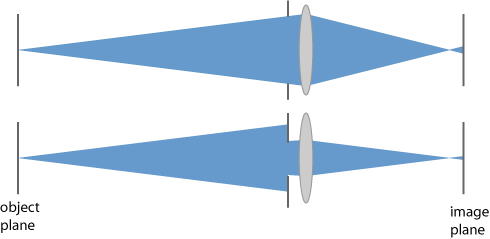

Focus

Diaphragm – Aperture

Shutter – Time

Lesson 2 – Photography techniques – Diaphragm and shutter speed

Slow shutter speed

Can you see an evidence, a proof of a slow shutter?

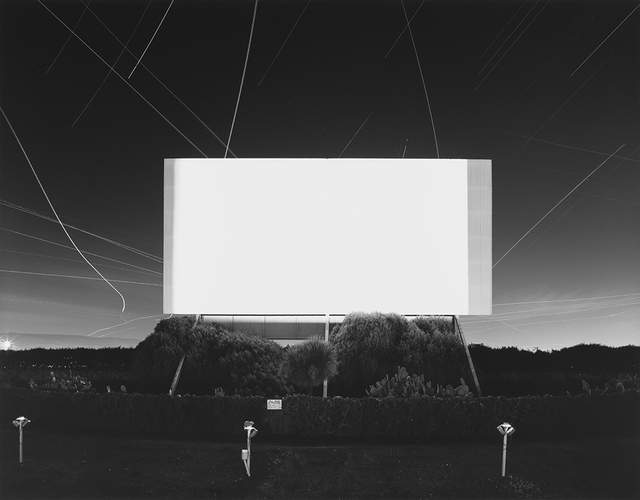

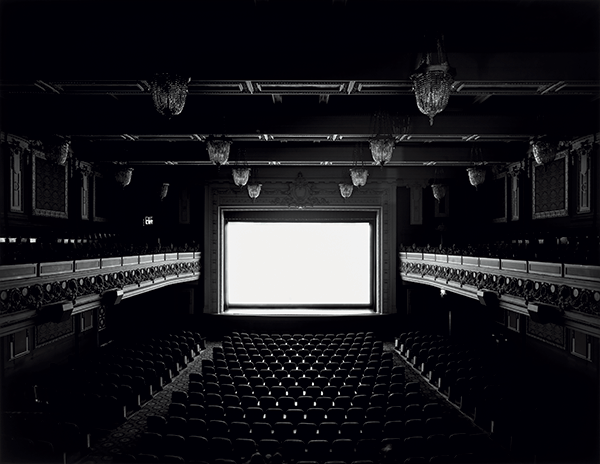

Contemporary

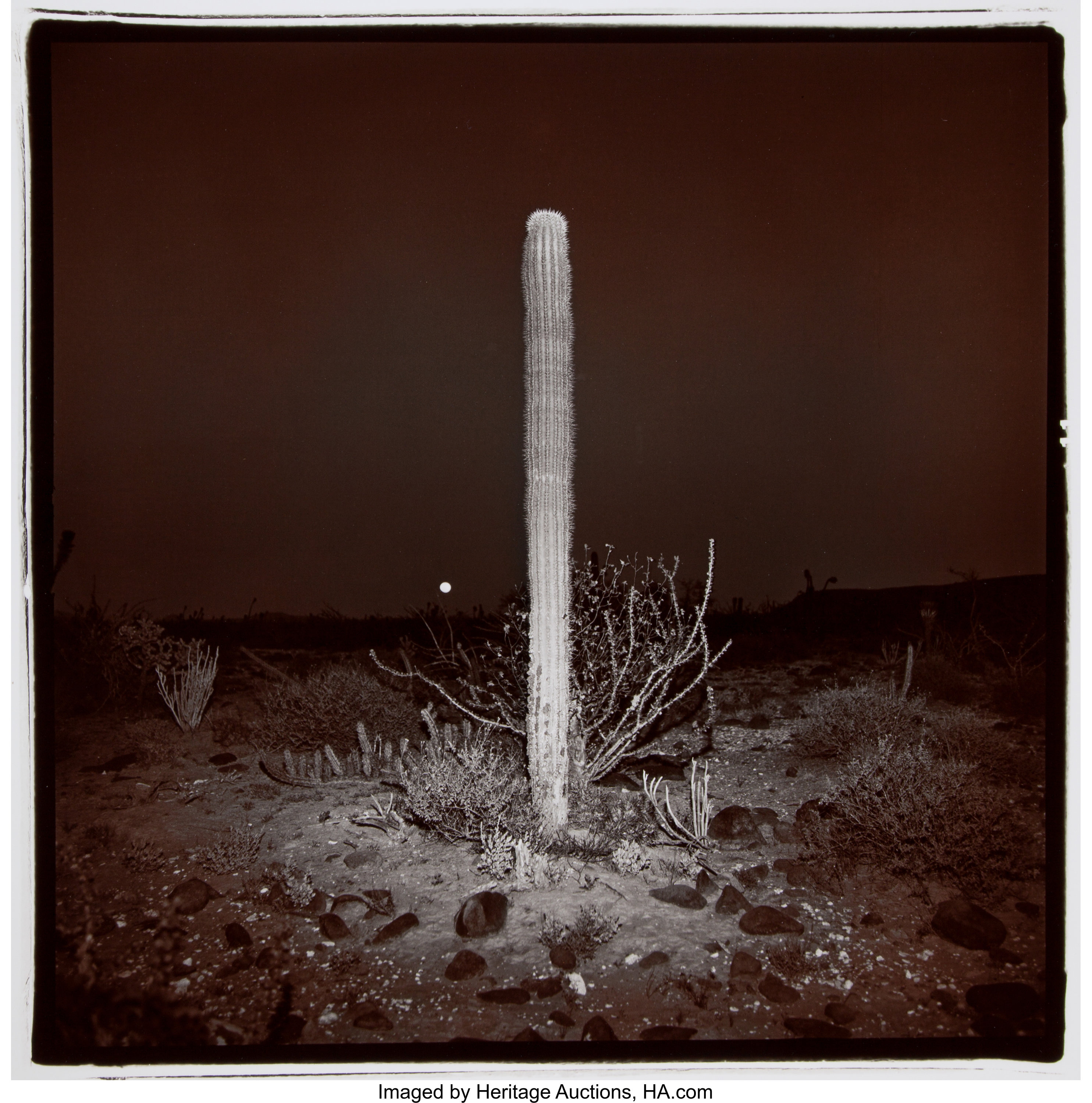

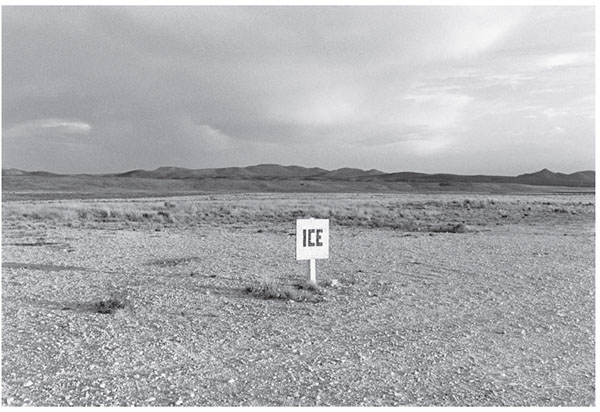

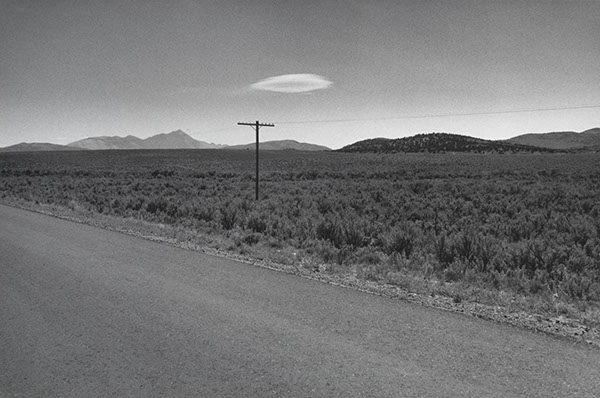

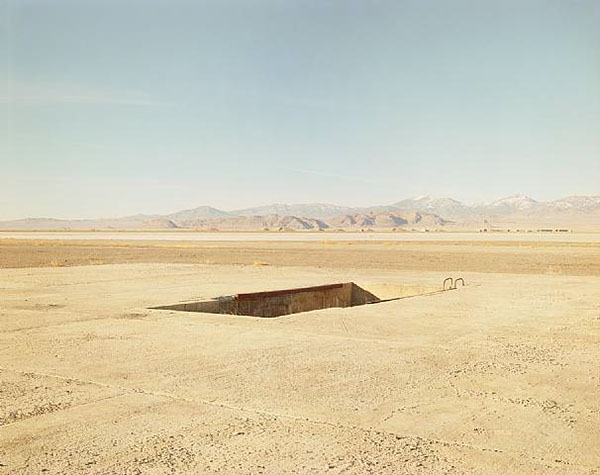

Richard Misrach

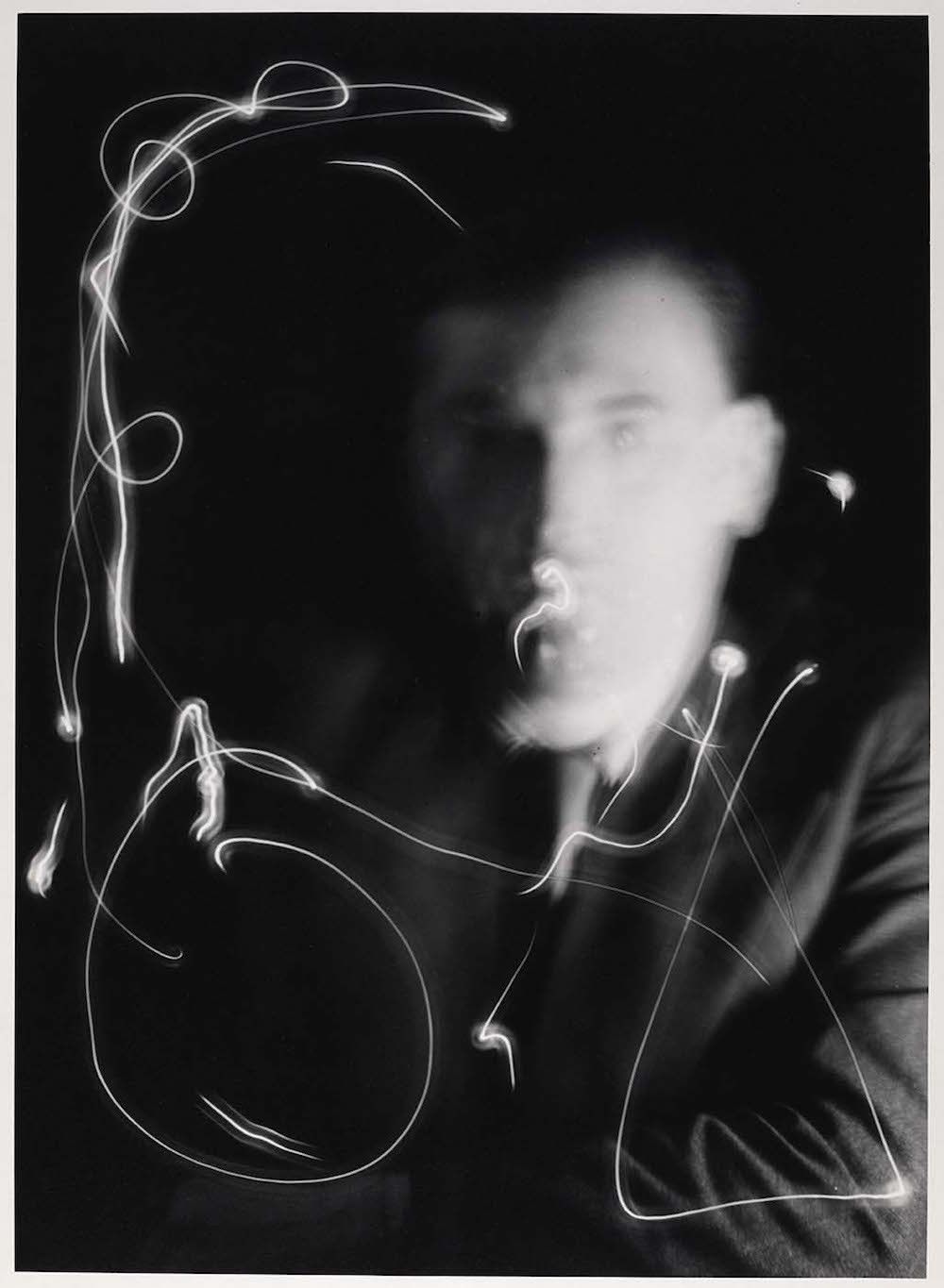

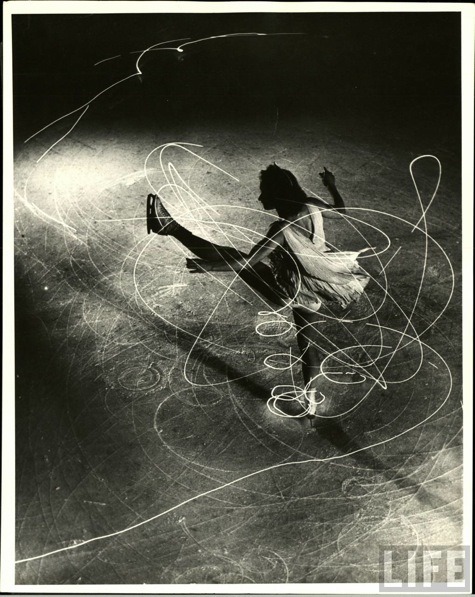

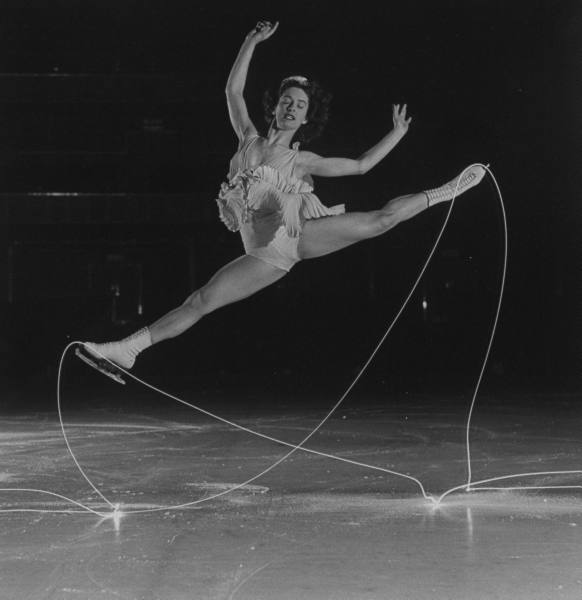

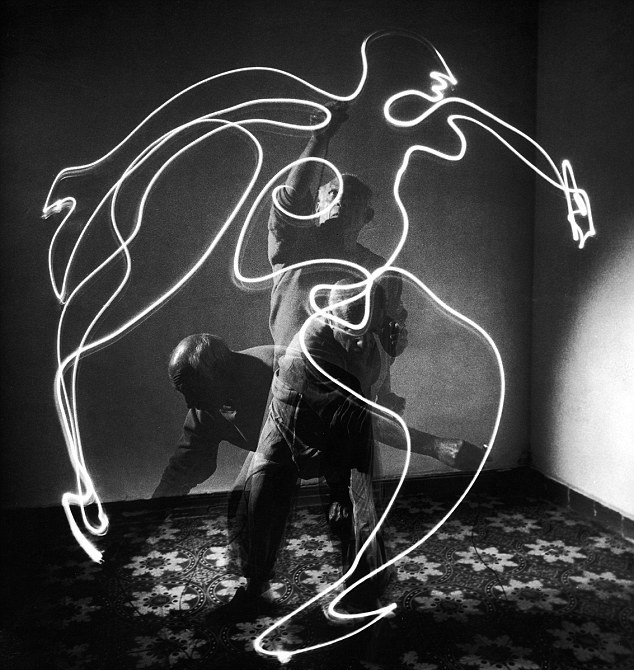

Light painting

See Muybridge animal locomotion in History link.

In 1949, while on assignment for Life Magazine, Gjon Mili was sent to photograph Pablo Picasso at his home in the South of France.

Brief history of light painting

Aperture & Depth of Field

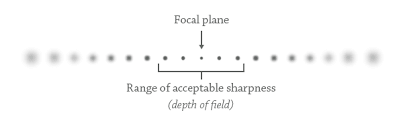

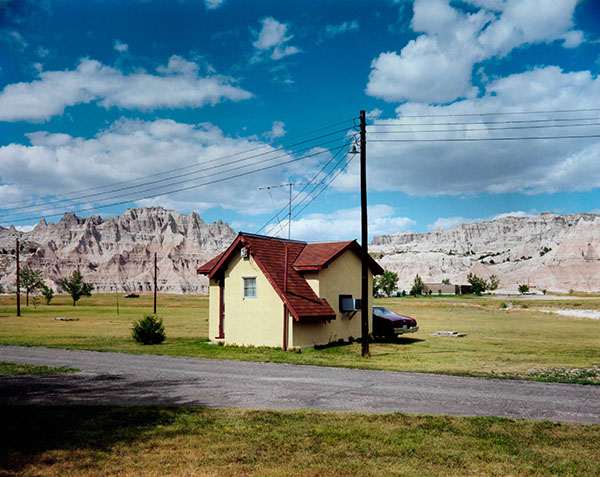

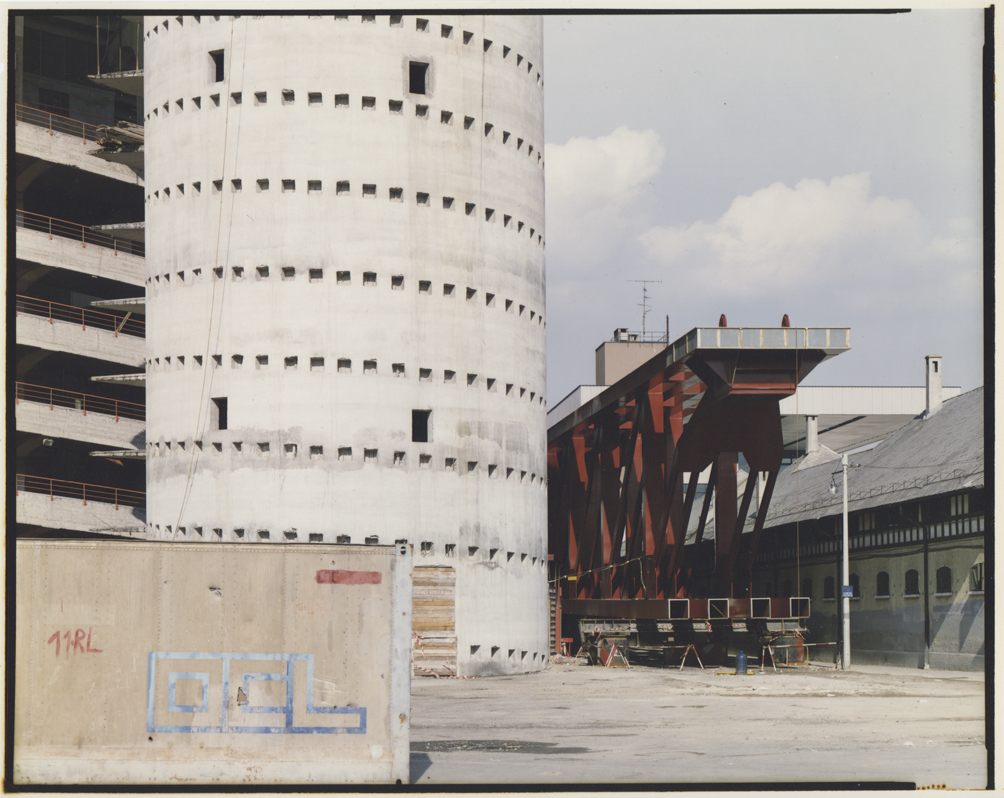

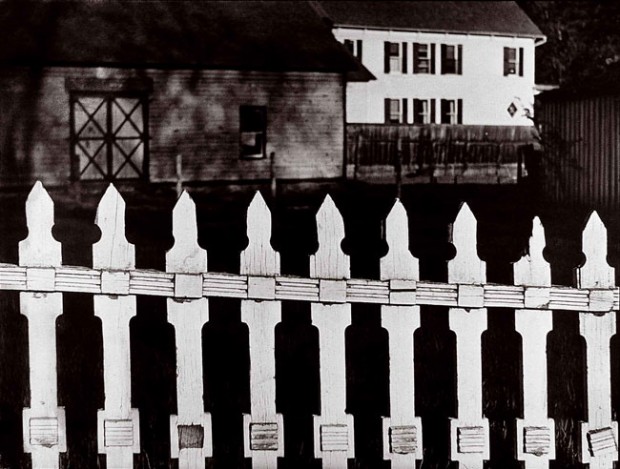

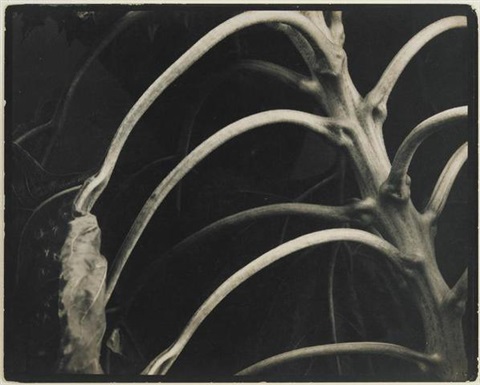

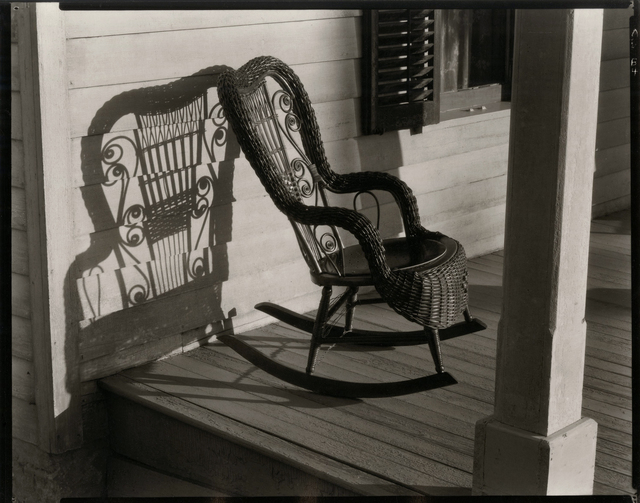

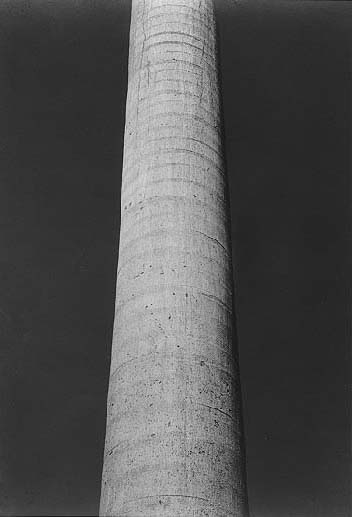

New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape

George Eastman House, Rochester, New York, 1975.

In 2014 MOMA acquired 619 prints from August’s grandson Gerd Sander.

Lesson 3 – Photography techniques – Movements of planes. Shift and perspective correction – Scheimpflug rule

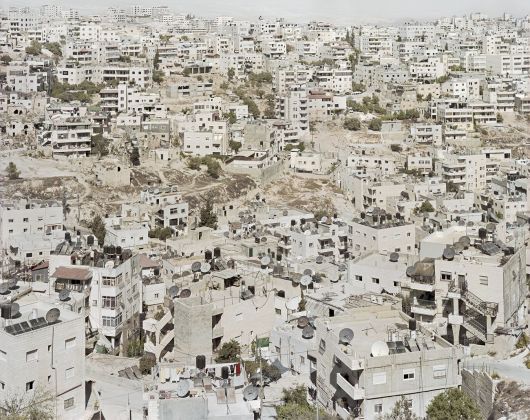

To control perspective and composition through rise, fall, side shift.

Rise:

Fall:

Side shift

To control focus through tilt and swing. The Scheimpflug rule.

Selective focus

Tilt-shift lenses for reflex photography

Exposition

Lesson 4 – History of Photography – The birth of the medium

Origins

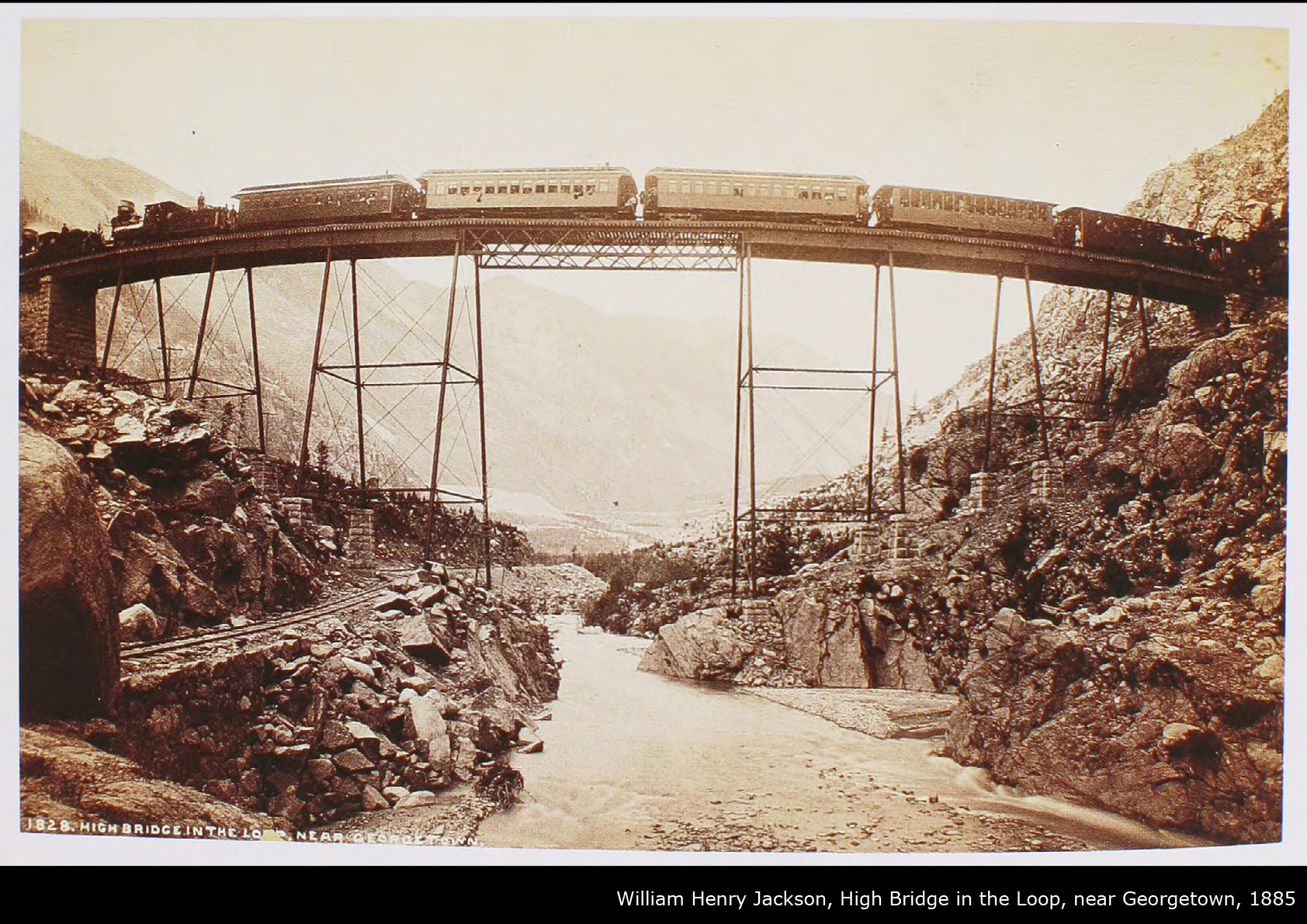

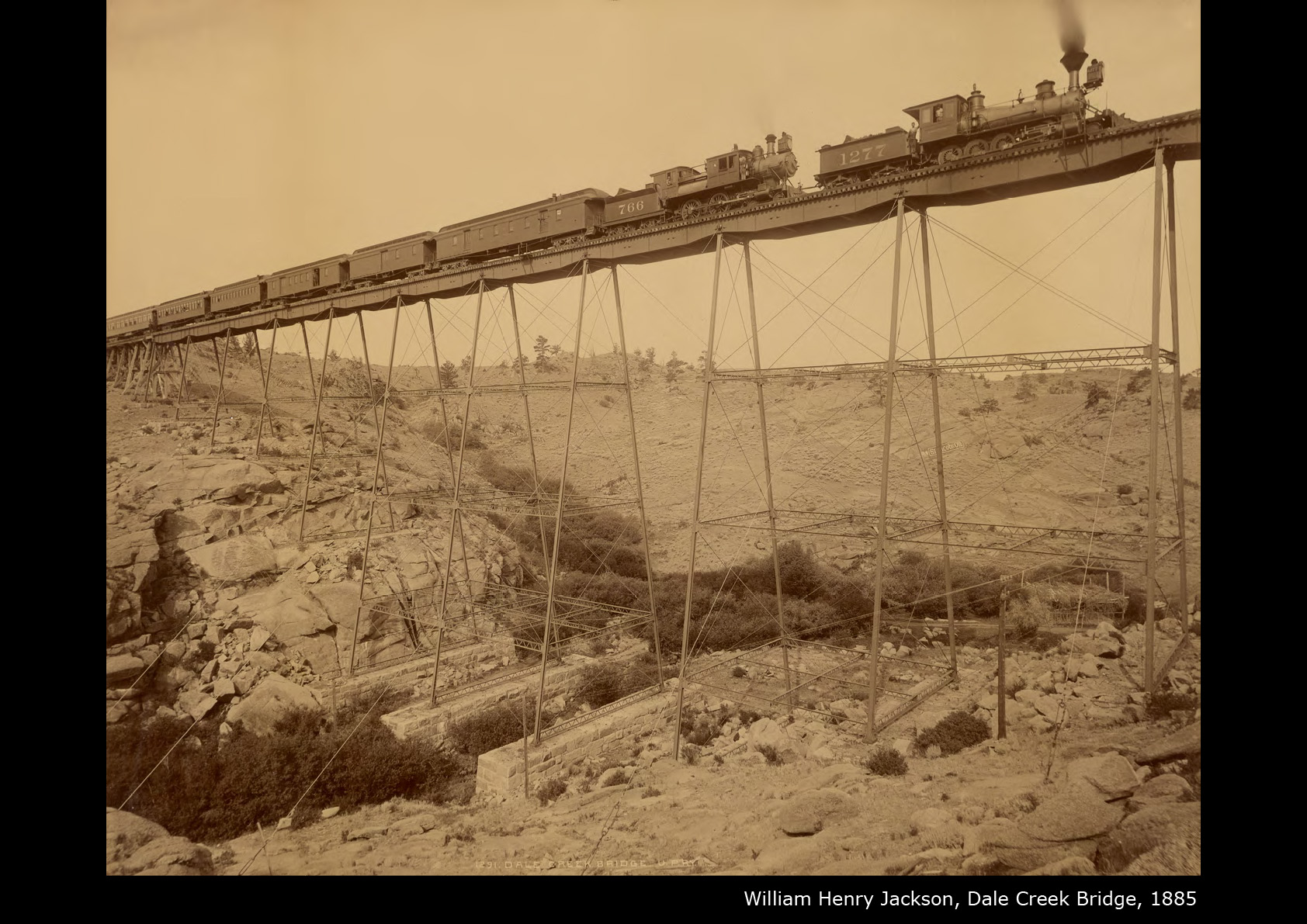

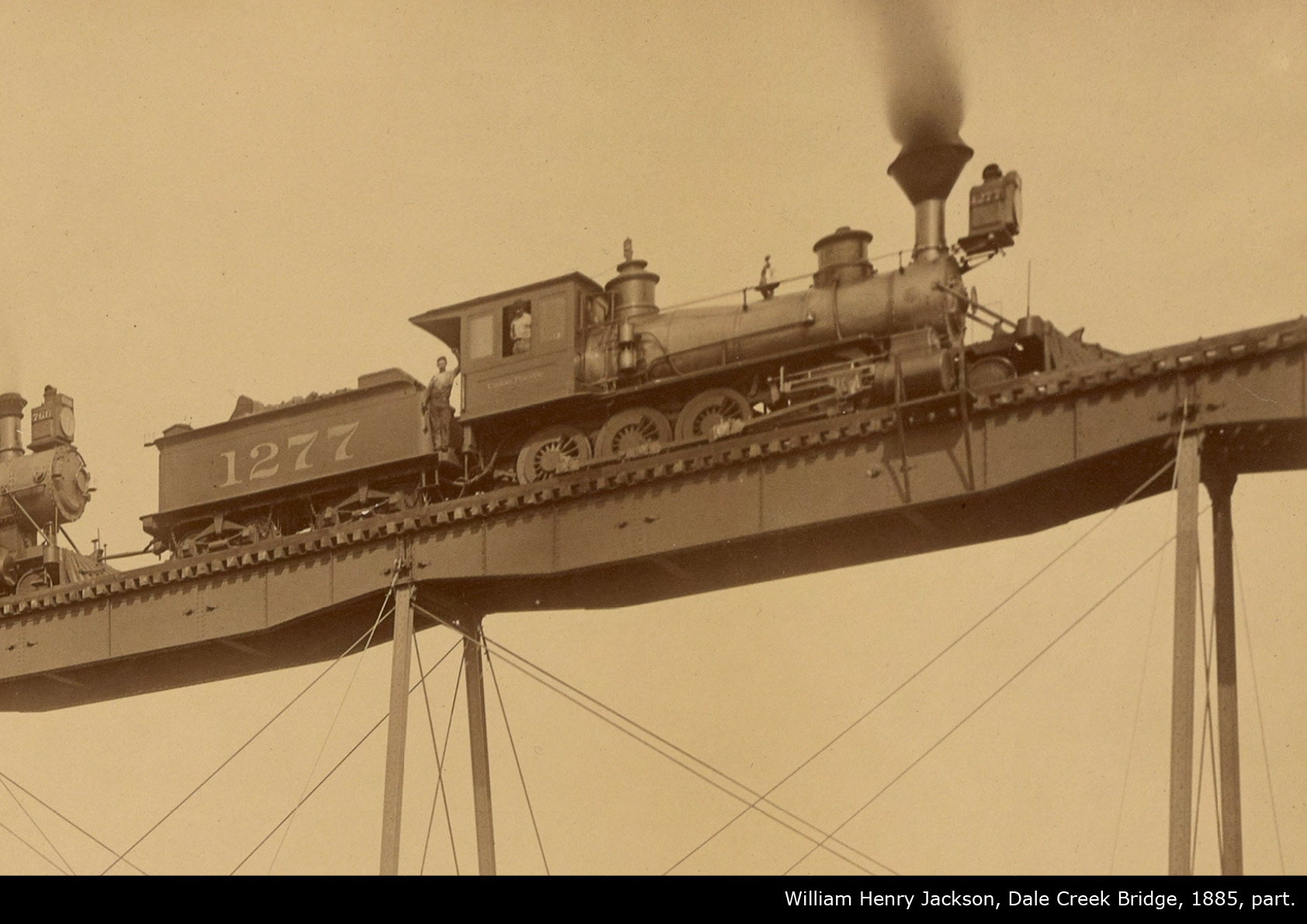

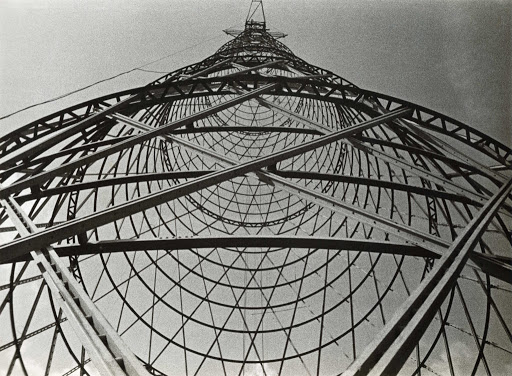

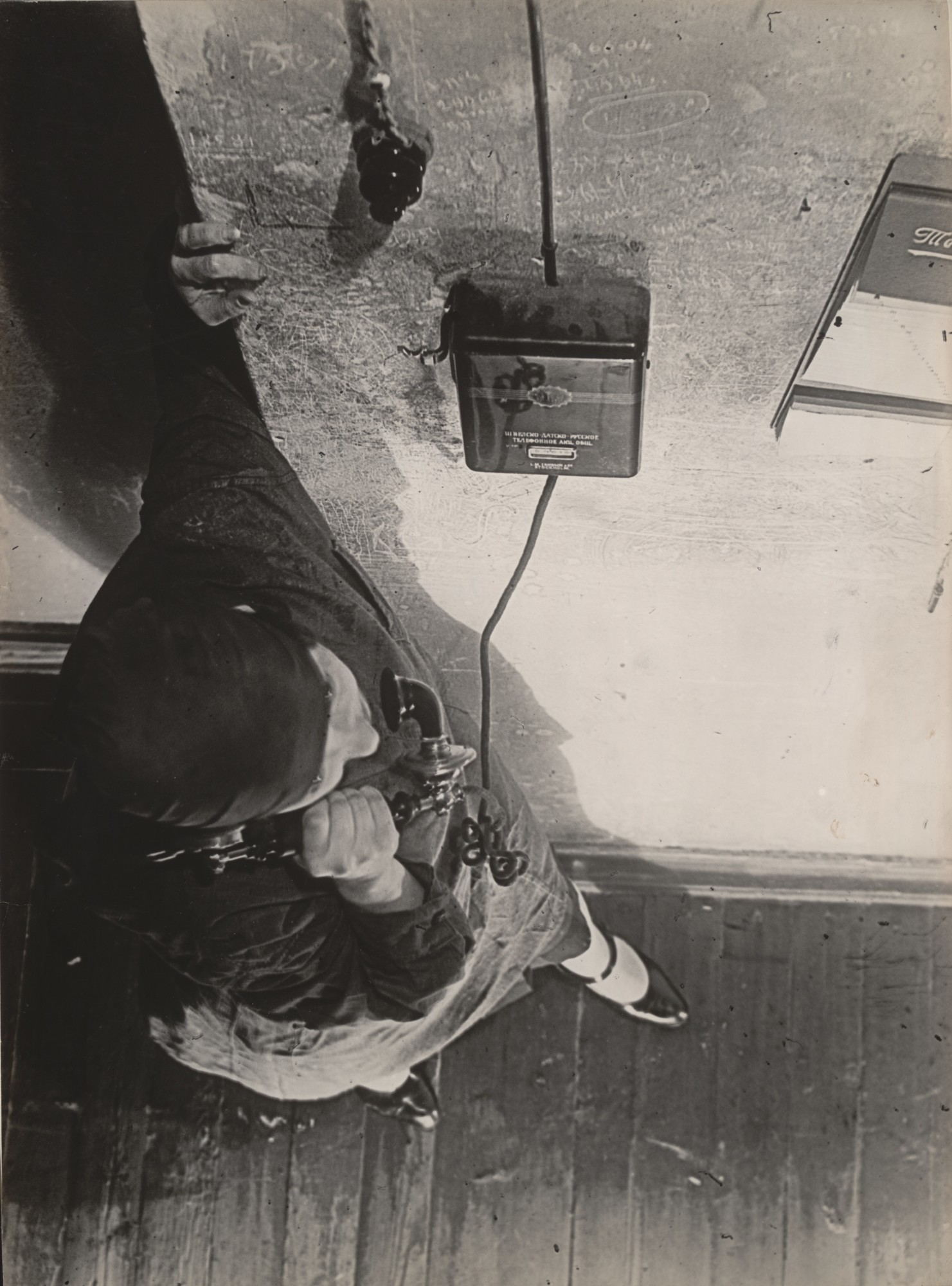

The coincidence with the industrial revolutions is obviously not coincidental: photography is to be considered as the necessary invention of an era, intertwined with the Progress of that time (the “P” is capitalized deliberately) and indispensable to document it.

And that link with the 19th century spirit of Progress and with the wonder and excitement that technology meant at that time, is also manifest at a formal level in the photographs of the time.

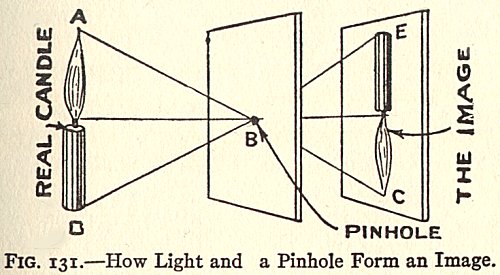

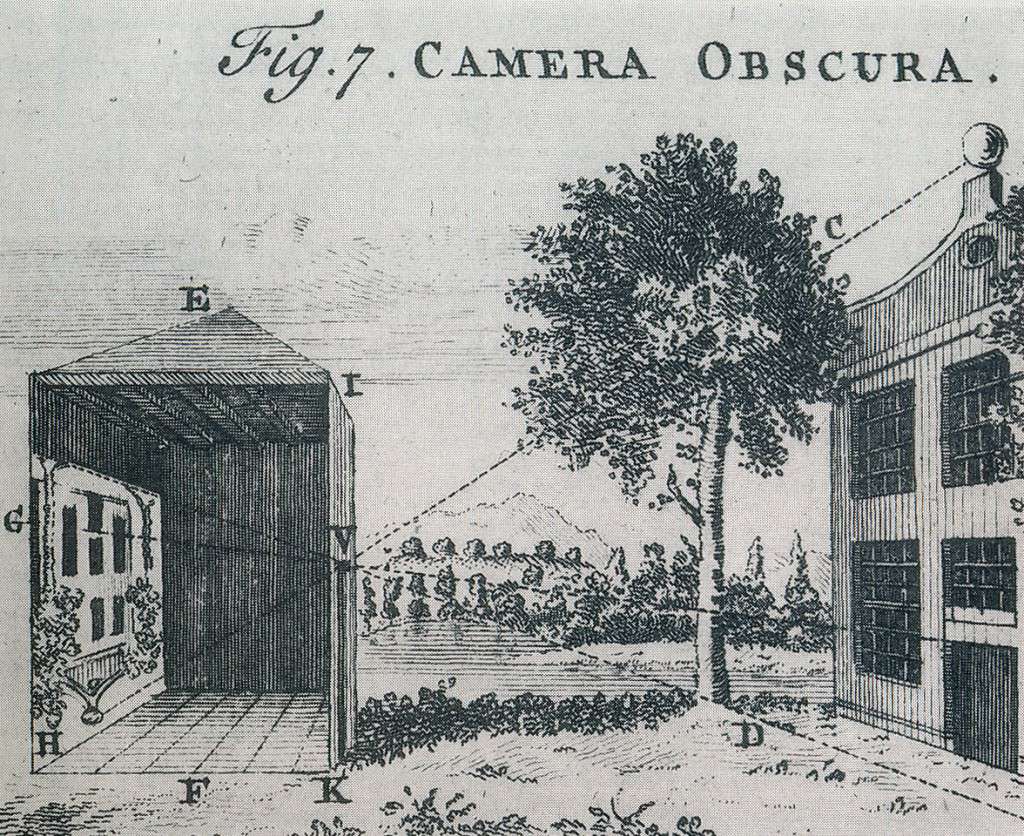

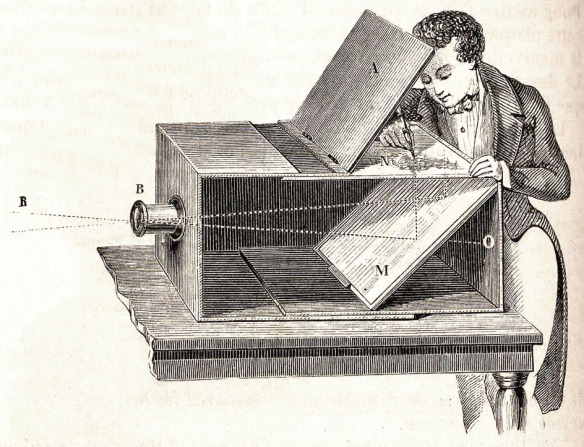

Having said that, the invention of the photographic instrument is based on more ancient inventions and researches that we can trace back to the theorization of linear geometric perspective (Leon Battista Alberti, Filippo Brunelleschi, Donato Bramante) and to the expedients of the darkroom.

Leon Battista Alberti, De pictura (1435):

“Here alone, leaving aside other things, I will tell what I do when I paint. First of all about where I draw. I inscribe a quadrangle of right angles, as large as I wish, which is considered to be an open window through which I see what I want to paint.”

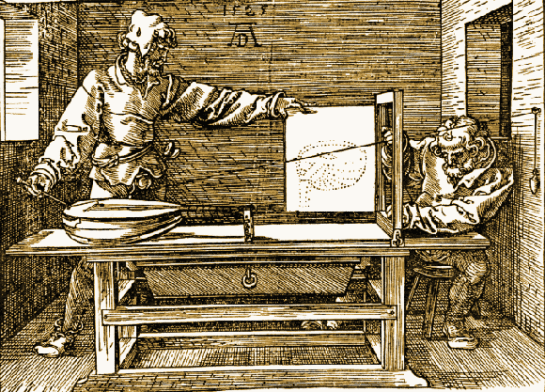

Albrecht Dürer (1525):

Jean Du Breuil:

Jean Du Breuil: A glass plate (A) slides through the rails (BC) and a viewfinder (F) constrains the view to a fixed point. The best way is to paint the contours directly on the glass that will then be moistened in order to adhere to an absorbent sheet on which the trace of ink present on the glass will be transferred.

Peter Greenaway, The Draughtsman’s Contract, 1982

Martina Bagicalupo – Gulu Real Art Studio

Luigi Ghirri – soglia

Daniel Crooks – Phantom Ride

Giovanni Battista della Porta described for the first time the camera obscura as a tool to help painters in their work in 1553 (treasuring the studies about light from Aristotle and the inventions of the astronomer Ibn al-Haytham of the eleventh century)

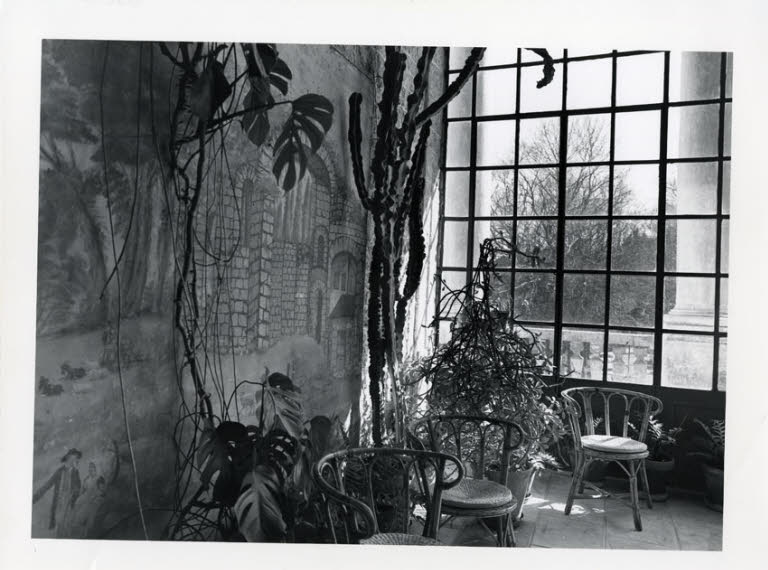

Abelardo Morrel, Camera obscura

https://www.abelardomorell.net/project/camera-obscura/Kingsley Ng

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qjorePSaMTQ&ab_channel=ArtBaselZoe Leonard

https://whitney.org/exhibitions/2014-biennial/zoe-leonardLater, to further facilitate the work of the painters the darkroom became portable. With different systems the image was transferred to a plane so that it could be copied by the artist.

Obviously the need to facilitate the work of painters had no cultural purpose: a new and urgent need for images was being born in society. The wonderful progress of the 19th century needed images to amaze the new man.

Painters and draughtsmen, however facilitated by these instruments of reproduction of reality, were no longer enough to fill the urge of seeing images.

How to fix images with the camera obscura?

1727 – Johann Heinrich Schultze – Scotophorus

By reproducing an ancient alchemical experiment (supposed to produce a luminescent substance that was made by mixing the chalk with the aqua regia), he realized that the compound became a dark purple when exposed to the rays of the sun. He called the compound Scotophorus (from the Greek, shadow bearer).

1802 – Thomas Wedgwood –

The son of a famous English ceramist, he used the darkroom to create drawings to be painted on ceramics. After studying Schultze’s experiment, he tried to sensitize paper or leather with silver nitrate and then, before exposing the sensitized surface to light, he placed objects or drawings on translucent paper on it.

He was unable to find a way to desensitize the remaining substances after exposure to prevent the rest of the image from being obscured when exposed to light.

1827 – Joseph-Nicéphore Niepce – Eliography

Inventor, he had patented with his brother Claude an internal combustion engine (they called it Pyrèolophpore) with which they managed to move a boat up the river Saone.

When the first printing processes (etching, etching, lithography, xylography) became popular in France, he wanted to design pewter plates (an alloy of tin lighter and easier to handle than the plates usually used for printing) and needed many drawings for his experiments. Being not artistically gifted, he began to study a way to impress the image of the darkroom using previous research on silver compounds that blackened in light.

He writes to his brother: “what you predicted happened: the bottom of the painting is black and the objects are white, that is to say, clearer than the bottom”. It’s a description of a negative image.

Niepce, however, decides to focus in the search of a procedure to produce a direct positive, rather than on the inversion of the negative through the printing process.

He succeeded in 1827 with the Bitumen of Judea (used by the engravers to protect the plate where it was not engraved), as it hardened with light.

His son Isidore will later write:

“He spread the bitumen of Judea upon a clean pewter. On this layer he placed the engraving to be reproduced, after making it translucent, and exposed the whole to light. After a certain time, more or less long, depending on the intensity of the light, he immersed the plate in a solvent that, little by little, made the image appear, until then invisible. After these operations, in order to make it suitable for the incision, it immersed it in more or less acidulous water.

My father sent the plate to the engraver Lemaître, asking him to contribute with his ability to engrave the drawing more deeply. Monsieur Lemaître graciously agreed to my father’s request and made several proofs of the portrait of Cardinal d’Amboise…”

Basically, the dark drawing held the light, which passed through the white paper instead. Thus almost all the bitumen of Judea, exposed to light, hardened and became insoluble, but the bitumen under the black lines of the drawing remained soluble and could be removed with lavender oil. The metal so exposed could be partially etched and transformed into a plate ready for printing.

At that point Niepce began to try to impress the image of the darkroom with the same process. He understood that the metal left uncovered by the bitumen of Judea, instead of being etched, could be chemically blackened by laying the plate upside down on an open box containing iodine, whose vapours obscured the plate in the parts left uncovered (those in the shade and then exposed by a wash of the bitumen of Judea not hardened by the light).

The only preserved example of this first process is a view from the window of Niepce’s house at “Le Gras”.

It seems that the exposure lasted for almost eight hours: in such a period of time the sun, moving from east to west, illuminated both sides of the buildings, thus destroying the ‘modelling’ of the buildings and landscape.

Of another image on glass, apparently given to the French Photographic Society in 1890 by a member of the Niepce family, only a reproduction remains in the Bulletin of the same company. The glass plate mysteriously disappeared from the Société collection shortly after its acquisition.

Eager to present his discovery, Niepce went to London to see his brother, but stopped in Paris where he wanted to meet a painter who was researching the same field and from whom he had received a letter of invitation. The painter was Louise-Jacques-Mandè Daguerre, who had learned of the research of Niepce by Charles Chevalier the optician who built the lenses for the camera obscura for both.

1837 – Louise-Jacques-Mandè Daguerre – Daguerreotype

Daguerre, a Parisian painter working in the production and setting of theatrical sets (he designed sets for the Opéra national de Paris), became famous, with his partner Bouton, for the Diorama, a theatre specially designed for the display of large views (made with the darkroom) superimposed on light translucent curtains which dissolved into each other with great scenic effect, through a controlled lighting and backlight system.

In 1829 Daguerre and Niepce signed a corporate agreement to pool their research (Niepce’s idea and Daguerre’s perfect dark chambers and resources), but Niepce died only four years after the company’s inception.

Daguerre continued on his own, perfecting and modifying Niepce’s process in a personal way.

In 1835, a journalist from the Journal des Artiste leaked some information about the procedure: “Daguerre found a way to catch, on a plate prepared by him, the image produced by the darkroom… It leaves its imprint in chiaroscuro on the plate… A subsequent processing leaves the image preserved for an indefinite period… The physical sciences have probably never seen a wonder like this”.

In 1837 Daguerre managed to make a first photograph with a modified procedure, quite different from that of Niepce.

The daguerreotype is obtained by using a copper plate (the most common were 16×21 cm) on which a silver leaf has been applied, polished and placed upside down on a box containing iodine, whose vapours react with silver to form photosensitive silver iodide on the surface.

The plate must, therefore, be exposed within an hour and for a period of 10 to 15 minutes (it is therefore much more sensitive than Niepce’s pewter plates).

Development occurs through exposure to mercury vapors at about 60 °C (upside down on a box containing it), which whitens the areas previously exposed to light.

The final fixing is obtained with a strong solution of kitchen salt, which eliminates the last remaining residues of silver iodide and thus makes the plate relatively insensitive to further exposure to light.

In the same year Daguerre agreed with Isidore Niepce (the son of Nicephore) a new contract specifying that the new method would bear the name of Daguerre alone but that it would be published together with the method of Niepce in order to honor the name of his father. The contract also specified that the technique would be offered for sale with detailed technical instructions with 400 subscriptions at CHF 1000 each.

The sale was however blocked by Francois Arago, scientist, director of the Paris Observatory, secretary for life of the Academy of Sciences, and member of the Chamber of Deputies, who proposed to Daguerre to donate the two methods to the French State in exchange for a annuity. The Literary Gazette of 19 January 1839 published extracts of Arago’s report to the Academy:

“In the camera obscura, the image is perfectly defined when the lens is achromatic;

the same precision is seen in the images obtained by M. Daguerre, which represent all objects with a degree of perfection which no designer, however skillful, can equal, and finished, in all the details,

in a manner that exceeds belief. It is the light which forms the image, on a plate covered

with a particular coating. Now, how long a time does the light require to execute this

operation? In our climate, and in ordinary weather, eight or ten minutes; but, under a pure

sky, like that of Egypt, two, perhaps one minute, might suffice to execute the most

complex design.”

Considering the great utility of the discovery to the public, and the extreme simplicity

of the processes, which is such that any person may practice it, M. Arago is of opinion,

that it would be impossible, by means of a patent or otherwise, to secure to the inventor

the advantages which he ought to derive from it; and thinks that the best way would be

for the government to purchase the secret, and make it public. [..]

But who will say that it is not the work of some able draughtsman?

Who will assure us that they are not drawings in bistre or sepia?

M. Daguerre answers by putting an eyeglass into our hand. Then we perceive the smallest

folds of a piece of drapery; the lines of a landscape invisible to the naked eye. With the

aid of a spying-glass, we bring the distances near. In the mass of buildings, of

accessories, of imperceptible traits, which compose a view of Paris taken from the Pont

des Arts, we distinguish the smallest details; we count the paving-stones; we see the

humidity caused by the rain; we read the inscription on a shop sign. The effect becomes

more astonishing if you employ the microscope. An insect of the size of a pea, the garden

spider, enormously magnified by a solar microscope, is reflected in the same dimensions

by the marvelous mirror, and with the most minute accuracy. It is manifest how useful

M. Daguerre’s discovery will be in the study of natural history.”

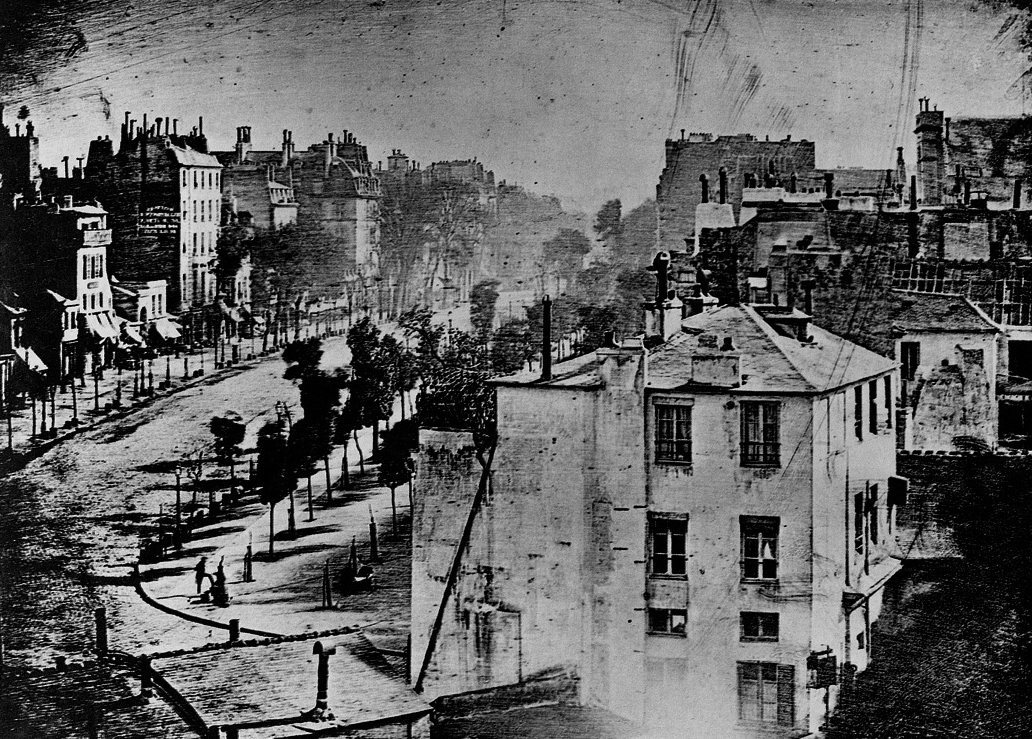

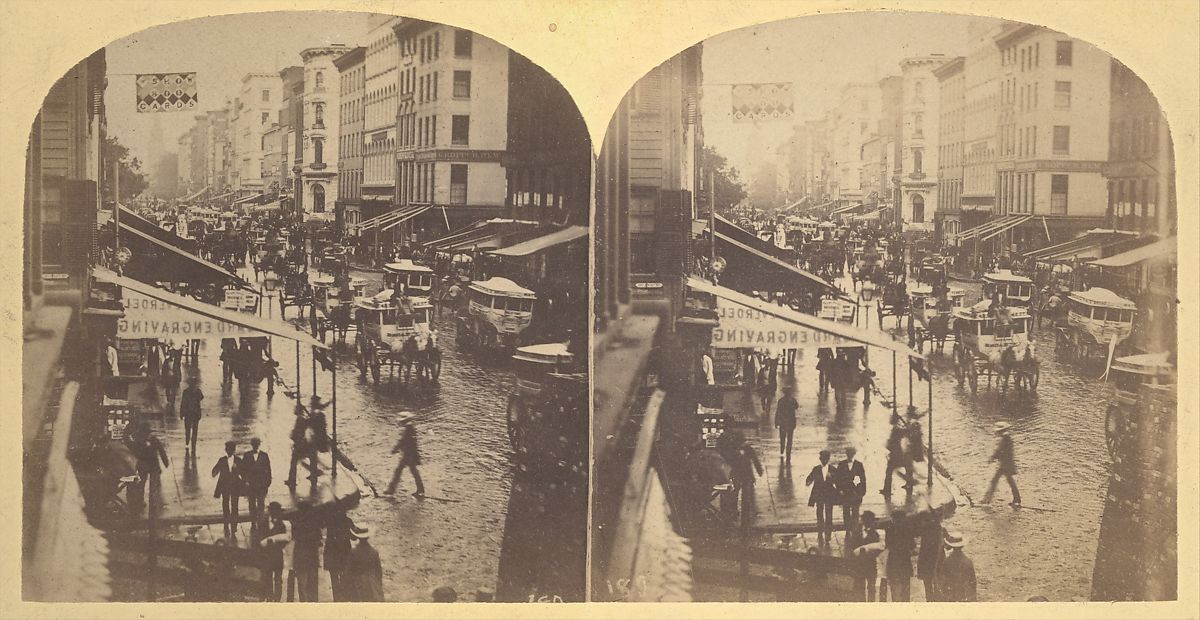

Daguerre’s most famous daguerreotypes are two Views of the Boulevard du Temple in Paris, taken on the same day (1838).

Samuel Morse was visiting Paris at the time of the announcement of the French Academy and he met Daguerre at the Diorama Theatre to show him his electromagnetic telegraph and see for himself daguerreotypes. Shocked by the discovery, he wrote to his brother, director of the Observer, who published his letter:

“[…] The day before yesterday, the 7th, I called M. Daguerre, at his rooms in the Diorama,

to see these admirable results. They are produced on a metallic surface, the principal pieces

about 7 inches by 5, and they resemble aquatint engravings; for they are in simple

chiaro scuro, and not in colours. But the exquisite minuteness of the delineation

cannot be conceived. No painting or engraving ever approached it. For example: in

a view up the street, a distant sign would be perceived, and the eye could just

discern that there were lines of letters upon it, but so minute as not to be read with

the naked eye. By the assistance of a powerful lens, which magnified fifty times,

applied to the delineation, every letter was clearly and distinctly legible, and so

also pavements of the street. The effects of the lens upon the picture was in a

great degree like that of the telescope in nature. Objects moving are not

impressed. The Boulevard, so constantly filled with a moving throng of pedestrians

and carriages was perfectly solitary, except an individual who was having his boots

brushed. His feet were compelled, of corse, to be stationary for some time, one

being on the box of the boot black, and the other on the round. Consequently his

boots and legs were well defined, but he is without body or head, because these

were in motion.” (The Observer, New York, April 20, 1839)

The popularity of Daguerre made other scientists, who in the same years had carried out similar studies, came forward to defend their own research.

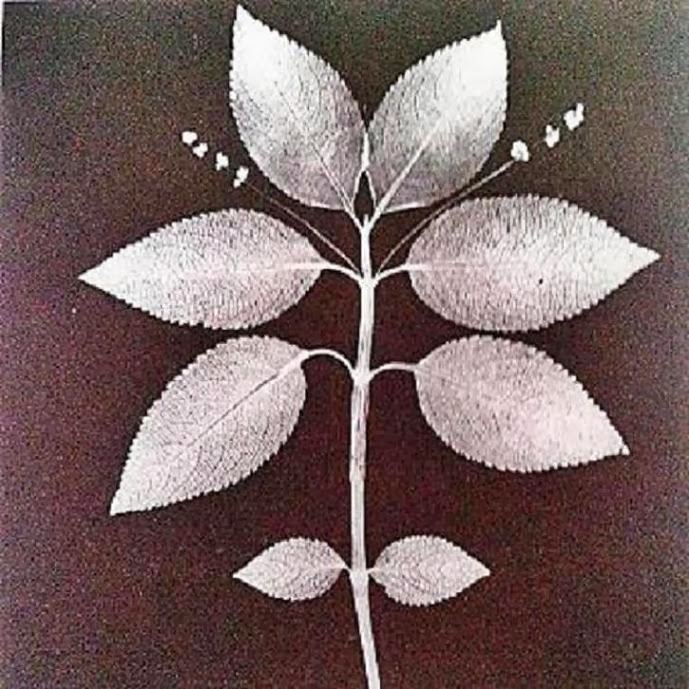

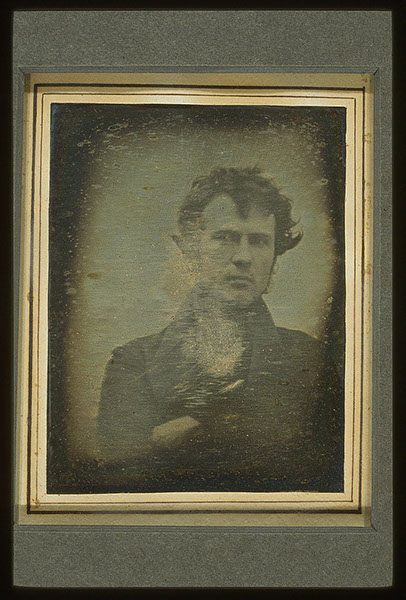

1835? – William Henry Fox Talbot – Shadowgraph or photogenic

A scientist, mathematician, botanist and philologist, a Cambridge graduate and a fellow of the Royal Society, he claimed to have invented a procedure since 1833 (in his opinion) to fix on paper images imprinted by the sun.

It soaked the paper in a solution of salt for cooking and then in a strong solution of silver nitrate thus forming silver chloride in the paper, sensitive to light and not soluble in water. On the paper thus prepared lay an object (solid with translucent parts) like a leaf, a lace or a feather, and exposed to the sun.

Talbot went further by describing, as early as 1835, how to derive a positive image from this negative image: “if the paper is transparent, the first drawing can serve as an object, to produce a second drawing, in which light and shadows will appear inverted” (therefore right, positive).

Talbot repeated the experiments with small dark rooms and, to fix the negative, dipped the paper, after exposure, in another even stronger solution of kitchen salt, but this fixing proved to be partial and the image ended up blackening completely as it was exposed to light.

Talbot suspended the experiments with the intention of resuming them in the future, until the announcement of Daguerre’s discovery. He tried to present a report of his research to the Royal Society and on 29 January 1839 he wrote three identical letters to Arago, Biot and Humboldt (among the major promoters of Daguerre’s work) announcing that he would claim the paternity of the proceedings to “fix the images from the camera obscura and to ensure subsequent storage so that they could withstand full sunlight.”

1819? – John Herschel – Hyposulfite fix

The scientist writes on January 29, 1839 (the same day as Talbot’s letters):

“Attempted experiments in the last few days, after learning the secret of Daguerre and knowing that even Fox Talbot has obtained something similar. Three requirements: 1) very sensitive paper; 2) perfect darkroom; 3) means to block the further action of light.”

It is on this last point that he claims the priority of his research. As early as 1819 he had used sodium hyposulfite to fix his photographs (being also an amateur philologist he had first called the procedure “photography”).

On February 1st, Talbot met Herschel who explained his fixing technique. Talbot, with Herschel’s consent, wrote the procedure in a letter to the French Academy of Sciences, which published it in his periodical accounts. Daguerre immediately adopted Herschel’s method for fixing.

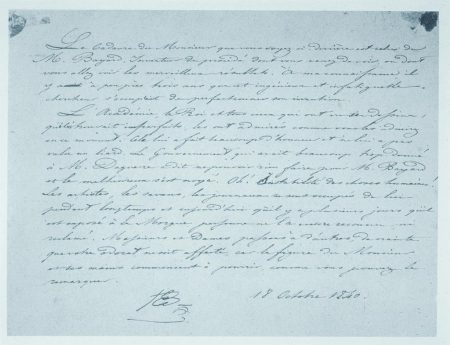

1839 – Hippolyte Bayard – direct paper positive

An official of the French Ministry of Finance, he exhibited on 14 July 1839 thirty photographs obtained by a personal method: a sheet of paper with silver chloride was blackened completely keeping it in the light. Then it was immersed in a solution of potassium iodide and exposed in the darkroom.The light then re-discoloured the paper according to its intensity thus obtaining the first positive direct on paper.

In the heat of the daguerreotype’s invention, Bayard condensed his frustration into an 1840 photograph in which he portrayed himself half-naked, pretending to be dead. On the back he wrote:

“The corpse which you see here is that of M. Bayard, inventor of the process that has just been shown to you, or the wonderful results of which you will soon see. As far as I know, this inventive and indefatigable experimenter has been occupied for about three years with the perfection of his discovery. The Academy, the King, and all those who have seen his pictures admired them as you do at this very moment, although he himself considers them still imperfect. This has brought him much honor but not a single sou. The government, which has supported M. Daguerre more than is necessary, declared itself unable to do anything for M. Bayard, and the unhappy man threw himself into the water in despair. Oh, human fickleness! For a long time, artists, scientists, and the press took interest in him, but now that he has been lying in the morgue for days, no-one has recognized him or claimed him! Ladies and gentlemen, let’s talk of something else so that your sense of smell is not upset, for as you have probably noticed, the face and hands have already started to decompose.”

Signed “H.B. 18 October, 1840.”

It was the first photographic hoax, the first visual storytelling process, the first use of captions together with the image to achieve a complex narrative result, revealed that photography could lie and that you can go beyond the surface image.

1839 – Nationalization of photography

While the battle about the authorship of the invention continued (Hercule Florence, a French resident in Brazil, Hans Thoger Winther, Novegese lawyer, and others added themselves to the list of self-proclaimed inventors) Arago accelerated the process to “nationalize” the invention with the support of the Minister of the Interior Duchatel, who highlighted, during the debate in parliament, the beneficial effects that photography could have on the safety of citizens, thanks to the precision that ensured in the recognition of criminals (see Ando Gilardi, Wanted! History, technique and aesthetics of criminal photography, Mondadori 1993).

On July 7th, 6 daguerreotypes are exhibited in parliament.

On July 9th, the Chamber of Deputies, after a speech by Arago and the other supporters of Daguerre, approved a bill of nationalization and publication of the photographic process with 237 votes in favor against 3.

On August 2 Daguerre made a demonstration to the House of Peers who voted favorably (92 against 4).

On 7 August the king signed the law of acquisition by the state and approval of the annuity to Daguerre and Isidore Niepce.

In order to document all aspects of the proceedings and all legal questions concerning the invention, Daguerre issueded, with the publisher Lerebours (which we will meet later), a 79-page booklet entitled “Historique et description des Procédés du daguerréotype et du Diorama” containing the description of the procedure, technical tables and images, Arago’s report to the Chamber, the description of Niepce’s procedure, the texts of the agreements and their variations between Daguerre and Niepce.

The booklet can be viewed here: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k56753837/f76.item

Daguerre also agreed with his brother-in-law Alphonse Giroux to provide cameras for the consumer, fitted with Chevalier lenses (the optician who had manufactured Niepce’s and Daguerre’s lenses for their personal dark rooms). A label on the side stated “The Daguerreotype. No device is guaranteed unless it bears the signature of Mr. Daguerre and the mark of M.Giroux.”

On August 19th, the process was made public with a further session in parliament. Marc Anotine Gaudin, a French chemist from the same period, wrote:

“The Palac .was stormed by a swarm of the curious at the memorable sitting on 19 August, 1839, where the process was at long last divulged.

Although I came two hours beforehand, like many others I was barred from the hall (and) was…with the crowd for everything that happened outside.

At one moment an excited man comes out; he is surrounded, he is questioned, and he answers with a know-it-all air, that bitumen of Judea and lavender oil is the secret. Questions are multiplied but as he knows nothing more, we are reduced to talking about bitumen of Judea and lavender oil.

Soon a crowd surrounds a newcomer, more startled than the last. He tells us with no further comment that it is iodine and mercury…

Finally, the sitting is over, the secret divulged…

A few days later, opticians’ shops were crowded with amateurs panting for daguerreotype apparatus, and everywhere cameras were trained on buildings. Everyone wanted to record the view from his window, and he was lucky who at first trial formed a silhouette of roof tops against the sky. He went into ecstasies over chimneys, counted over and over roof tiles and chimney bricks – in a word, the technique was so new that even the poorest plate gave him unspeakable joy…..”

Lesson 5 (+1) – History of Photography – first uses

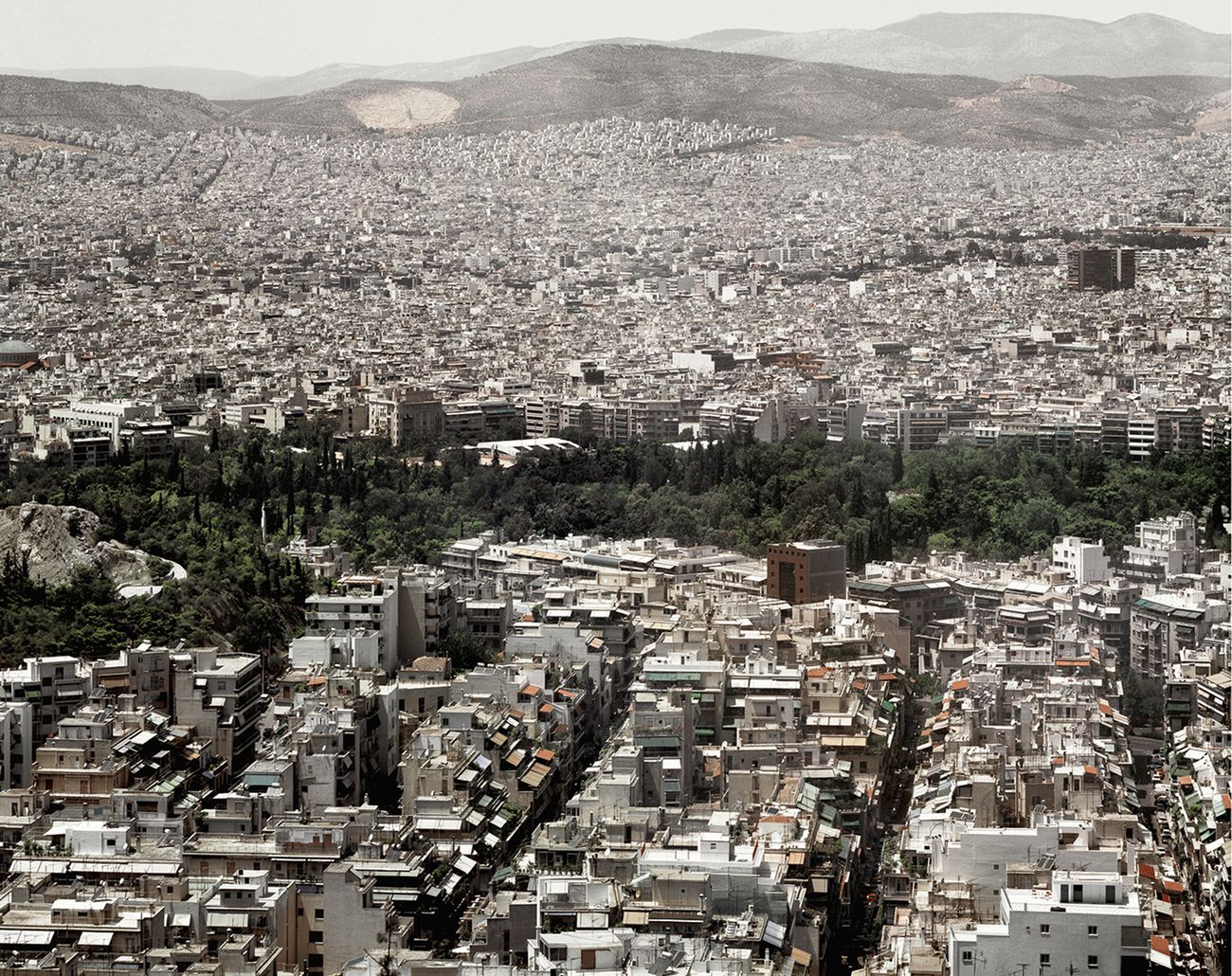

The wonder of seeing the landscape in the images

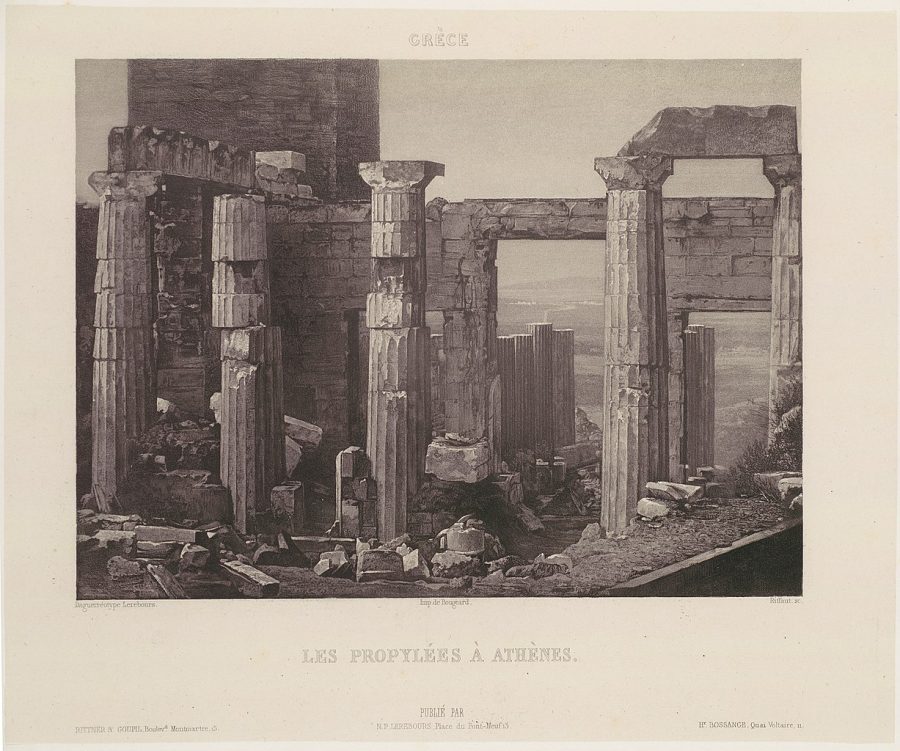

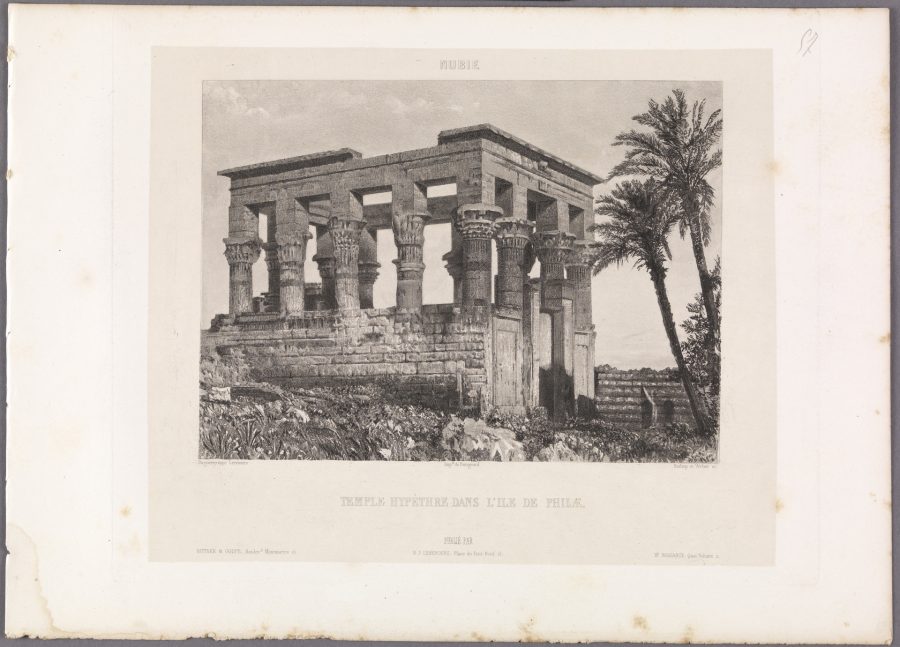

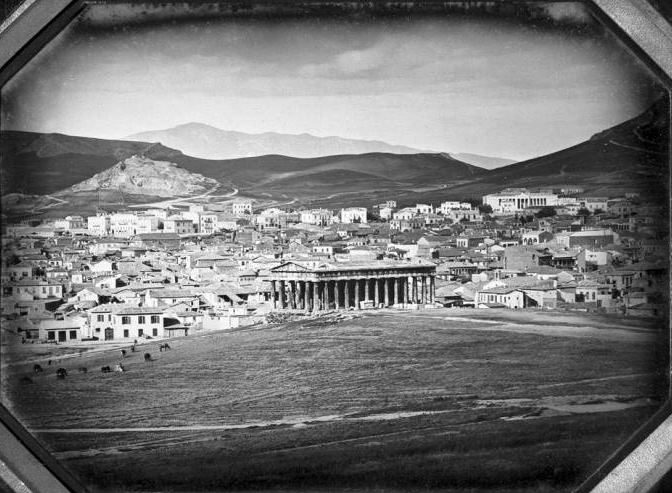

The first subject targeted by photographers was the landscape, both for the technical limit of long exposure times, and for the wonder of technological progress that the observer of an image felt at the dawn of his invention. The pure intention and technology of creating an optical image was sufficient to justify it and motivated its use. The mere looking was in itself surprising.

Just few days after the release of the invention on 19 August, the magazine Le Lithographe published a lithograph from a daguerreotype (this was for some years the standard process of replication of images obtained with daguerreotype, beyond the only positive original).

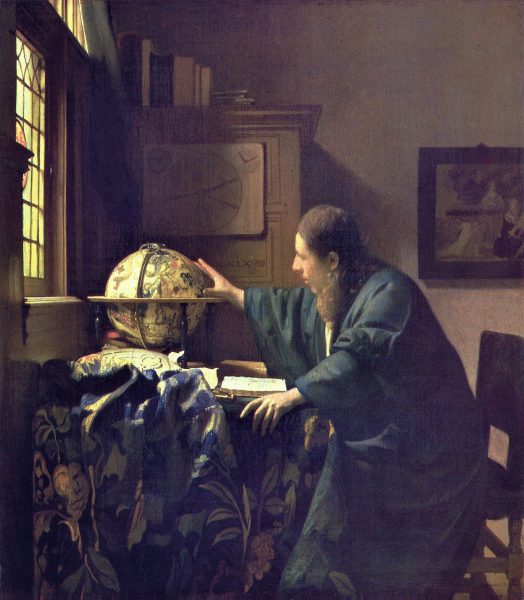

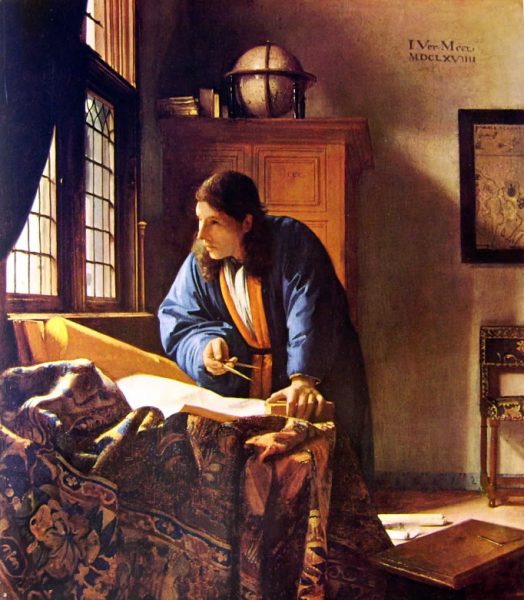

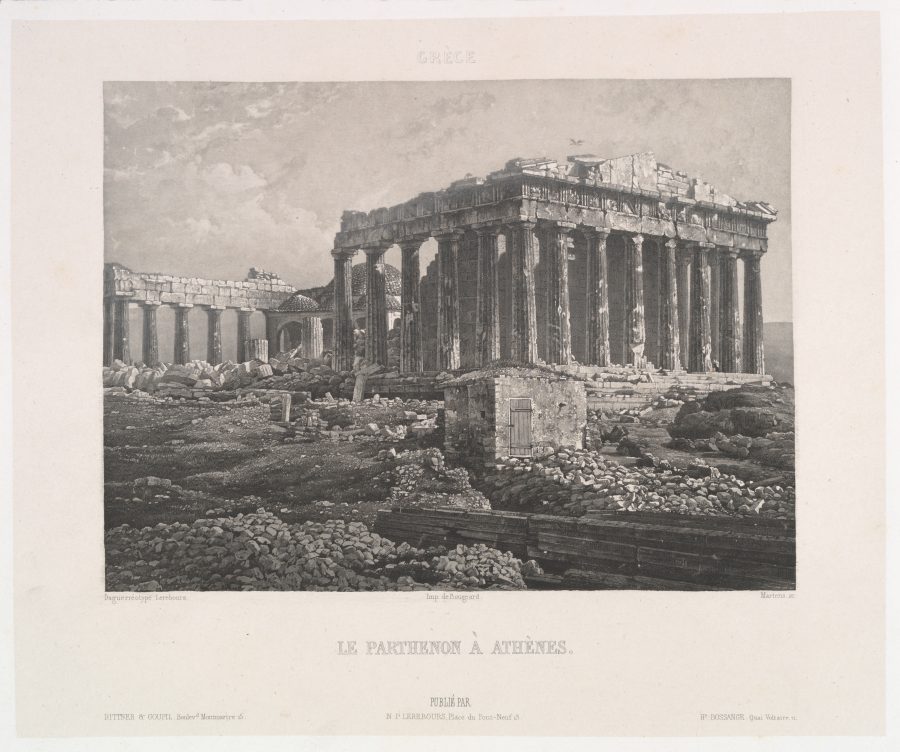

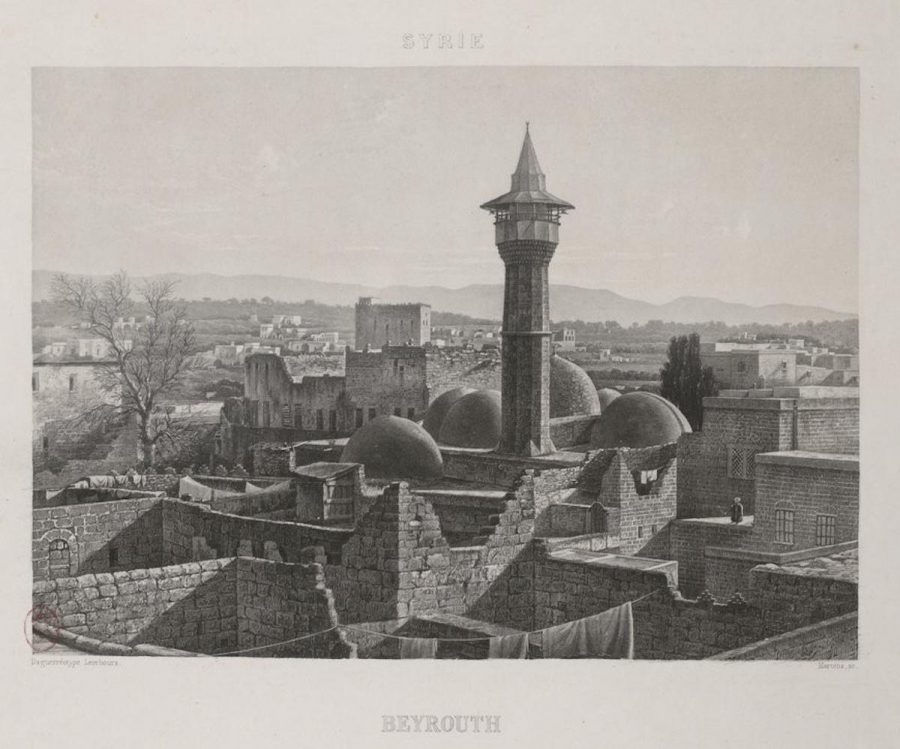

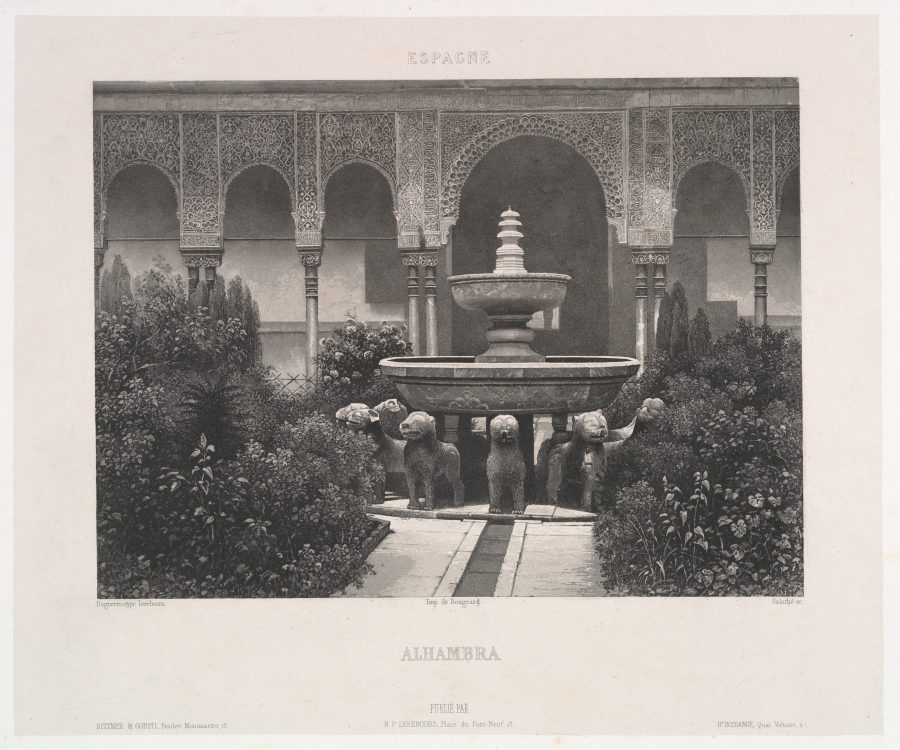

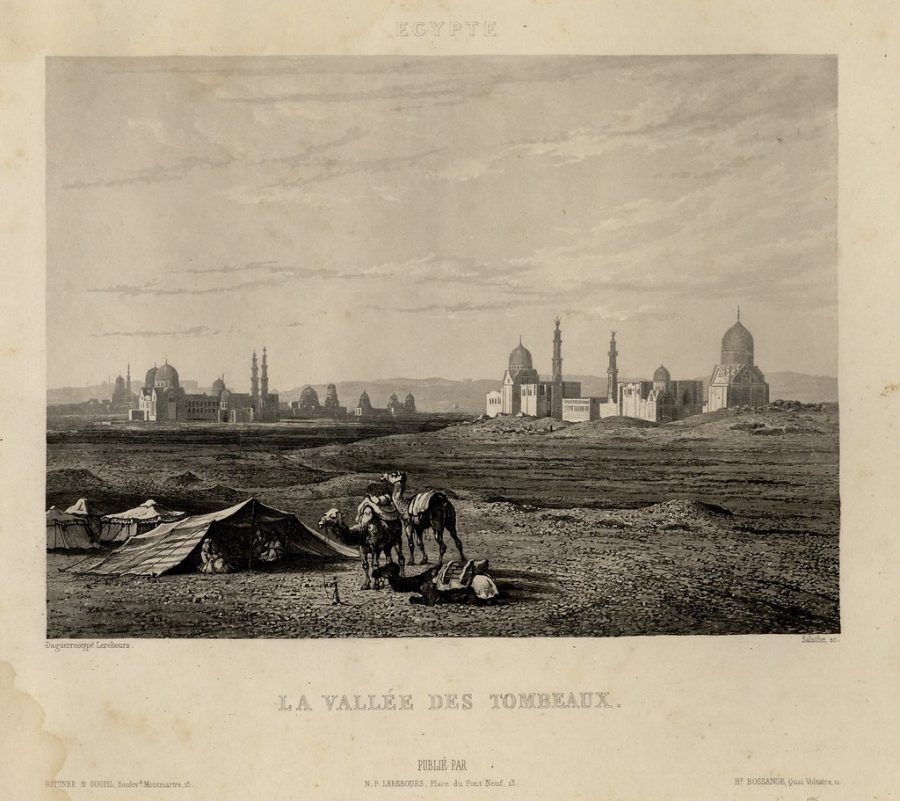

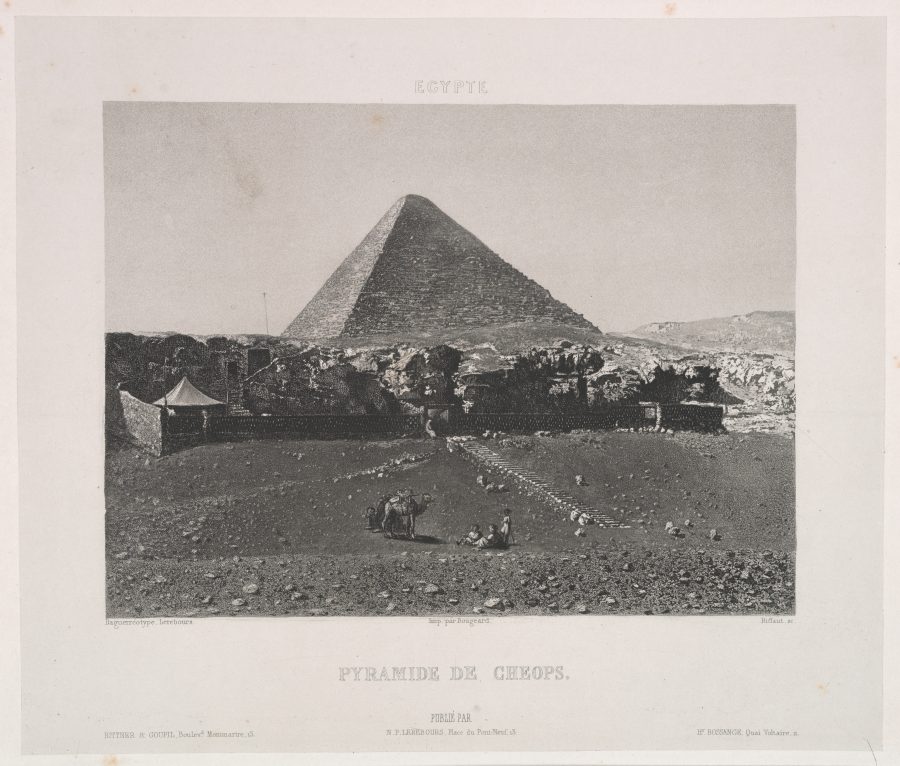

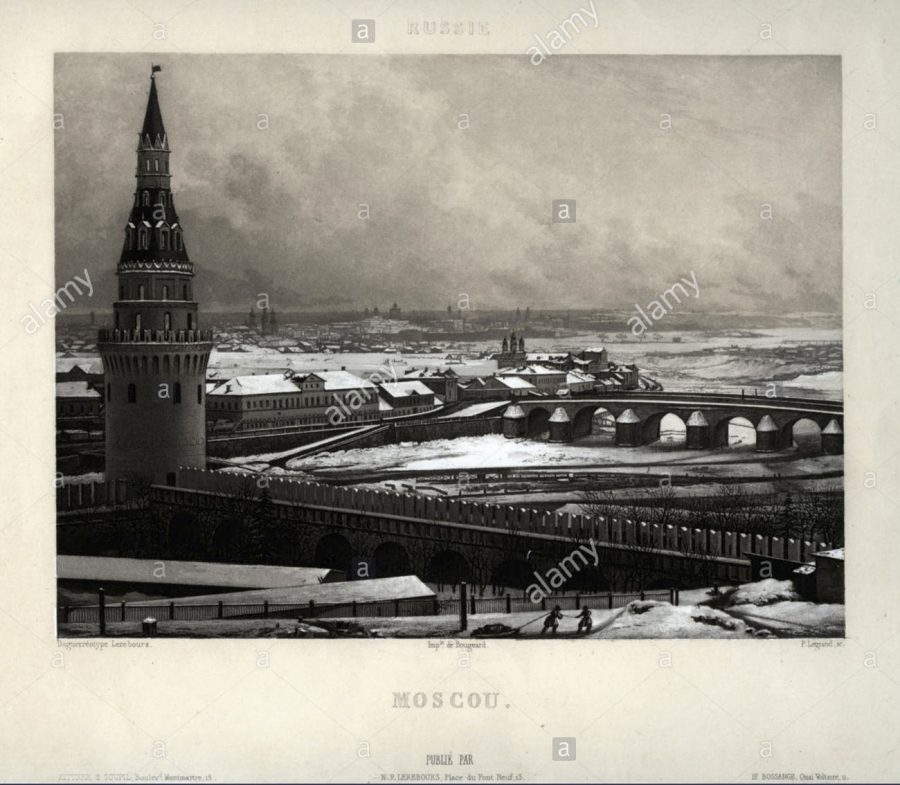

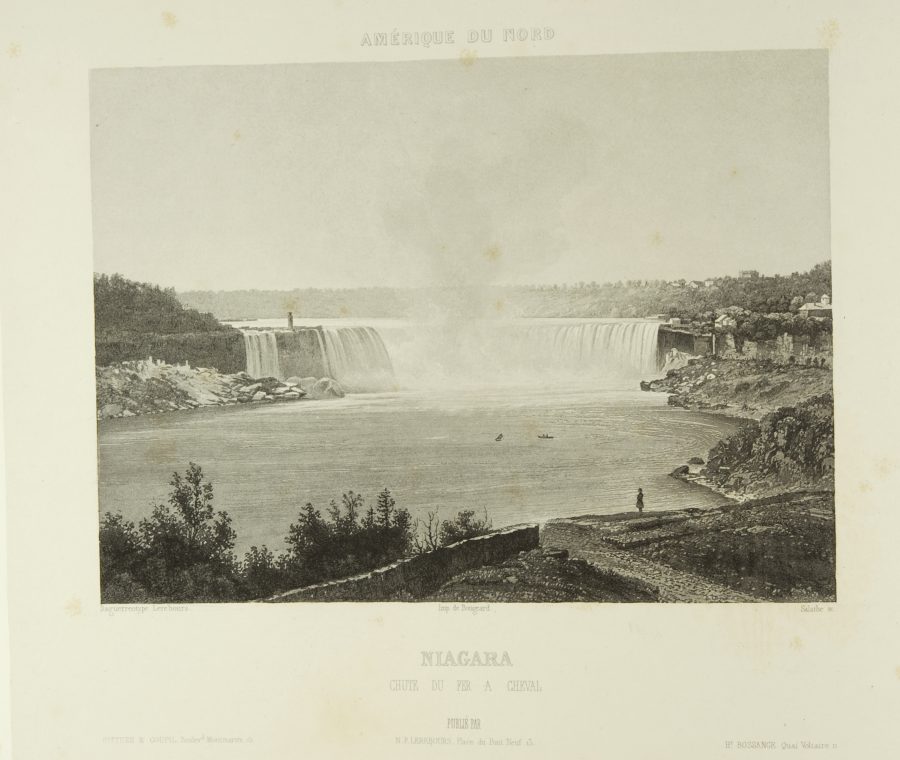

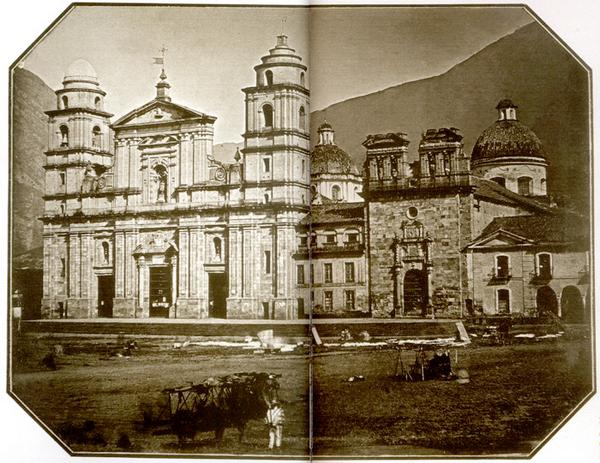

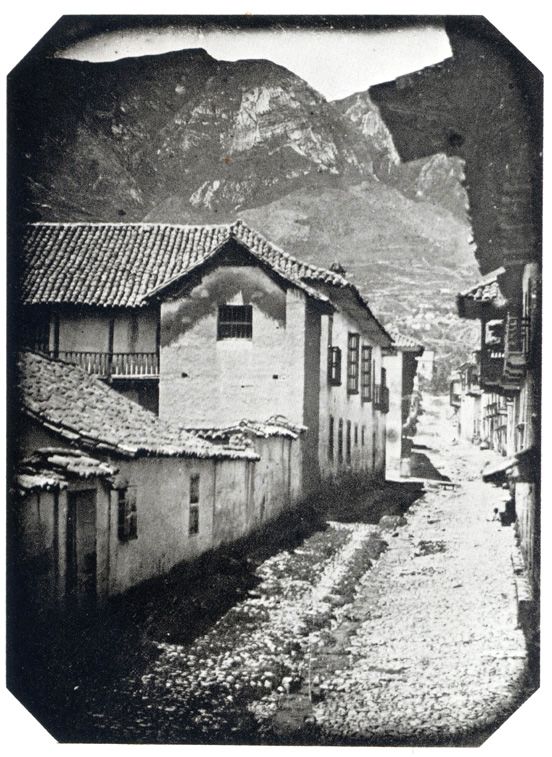

Between 1840 and 1844 the publisher Lerebours published a series of topographical views called Excursions Daguerriennes, 114 views from Europe, the Middle East and America, enriched with the addition of human figures designed to make up for the feeling of abandonment that was perceived by the absence of people.

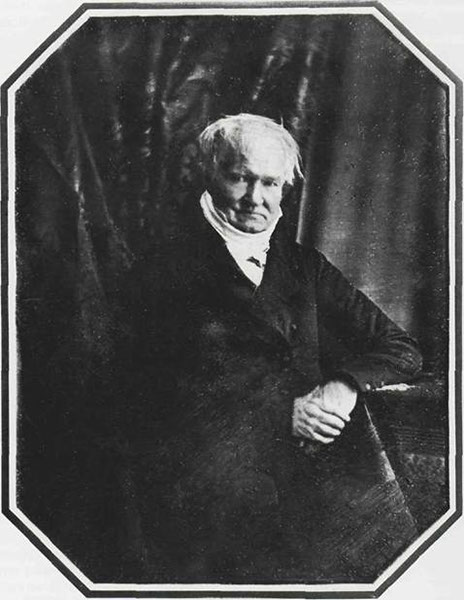

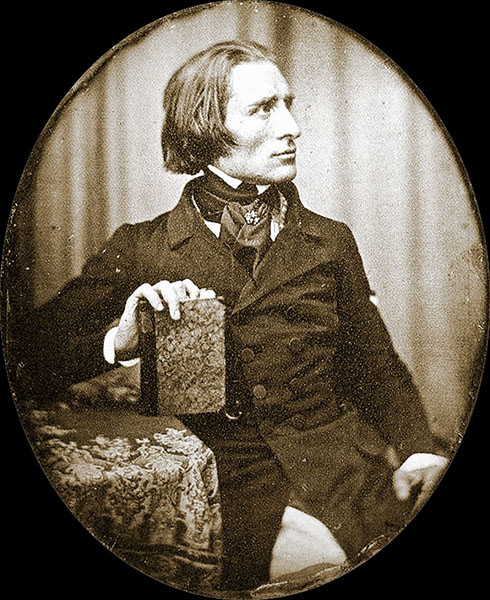

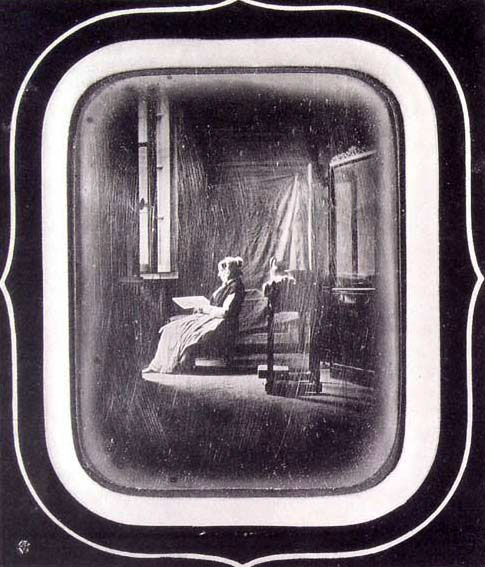

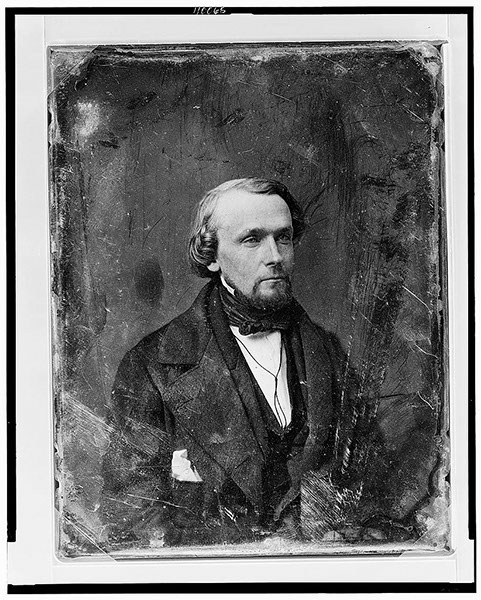

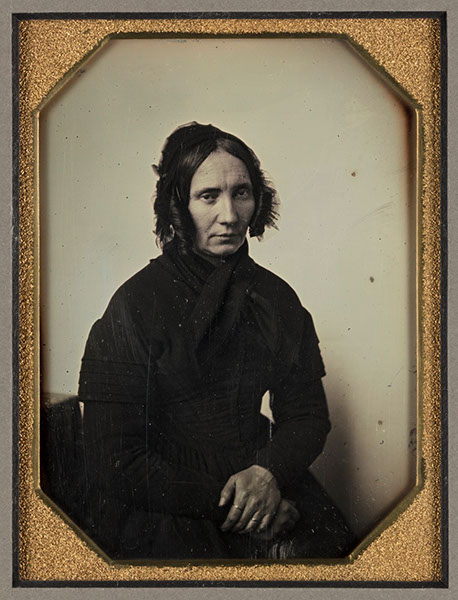

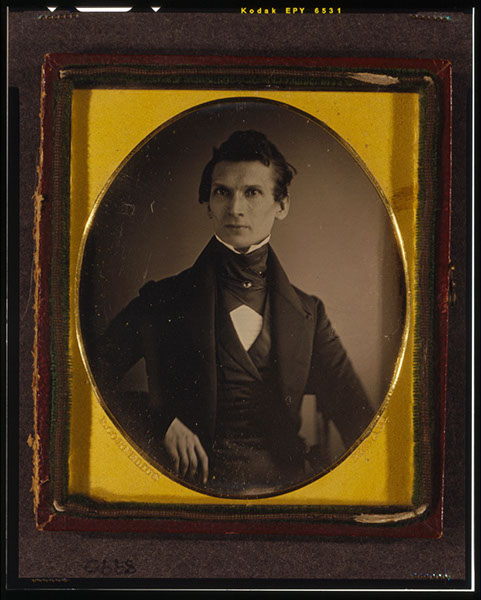

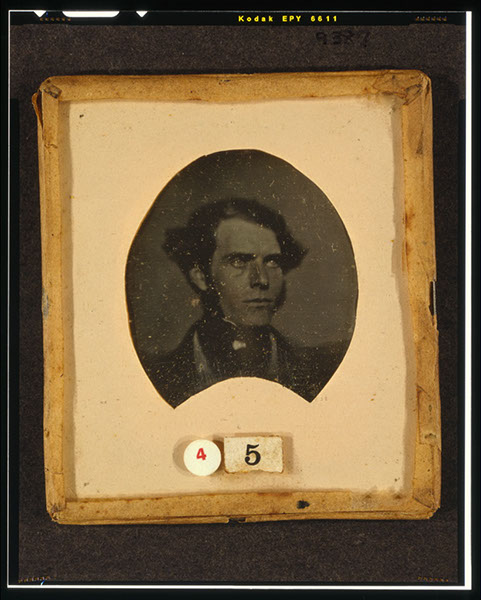

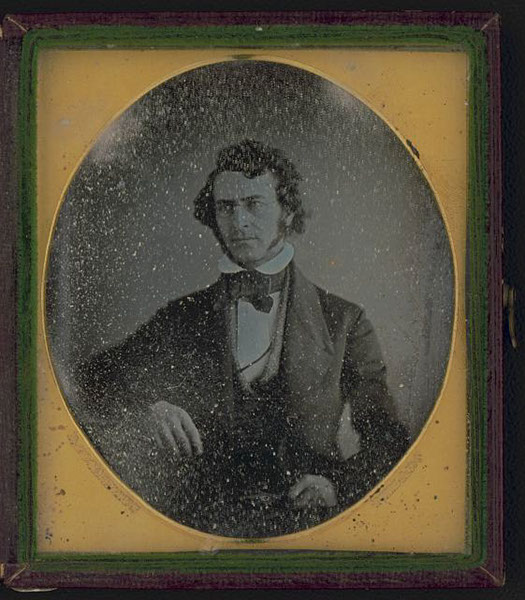

The wonder (and social acclaim) of seeing oneself in the images

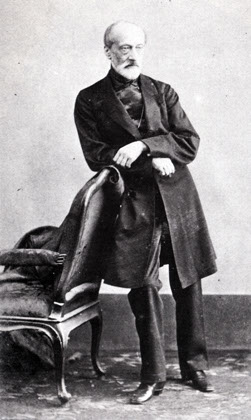

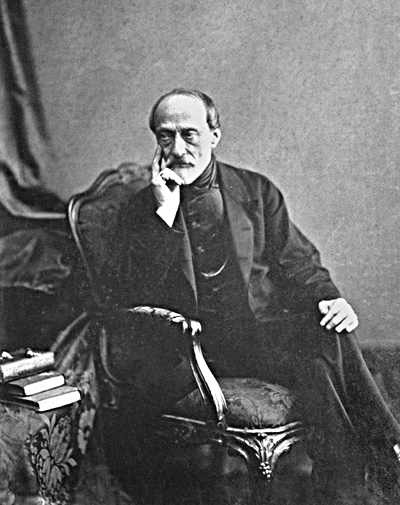

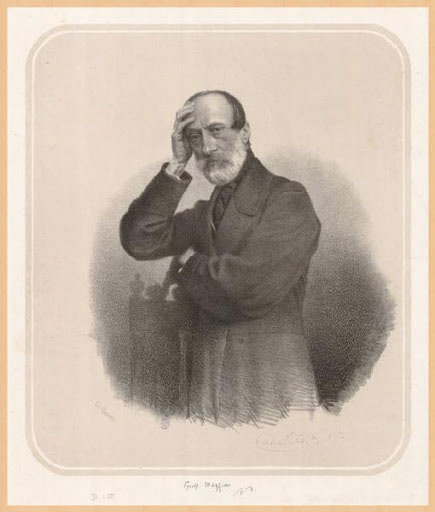

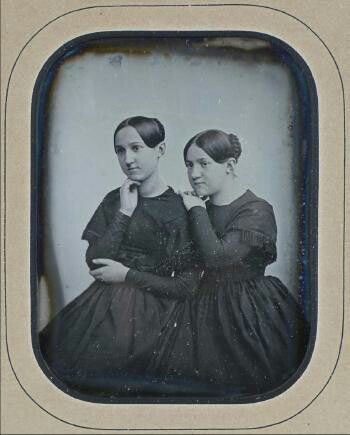

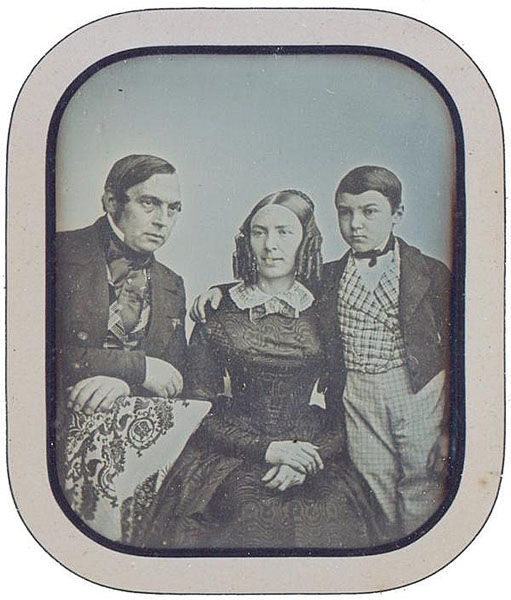

The other primary application of the invention was the portrait. The emerging bourgeoisie was the perfect target for the new photographic industry. Devoted to modernity, she identified her own condition with the technological progress represented by photography. If you want to participate in modernity, if you want to be “modern”, you have to be photographed. You must have images of distant landscapes (to participate in the discovery of the world) and you must have a portrait to demonstrate bourgeois victory.

This modernity for the bourgeoisie also meant the cancellation of the gap with an old world, that of the aristocracy, a gap that the bourgeoisie also wanted to break down materially by accessing practices and imaginary that were precisely the prerogative of the aristocracy.

Landscape photography, images of distant places, brought the bourgeois closer to the noble intellectual aristocrat who for a century visited the world to learn art, customs and traditions (the end of the grand-tour period is commonly identified with the birth of the railways around 1840, the same period we are talking about).

The photographic portrait allowed the bourgeois to have at home an image of the self, just as the aristocratic nobles had done for centuries through the expensive and slow hand of the painter.

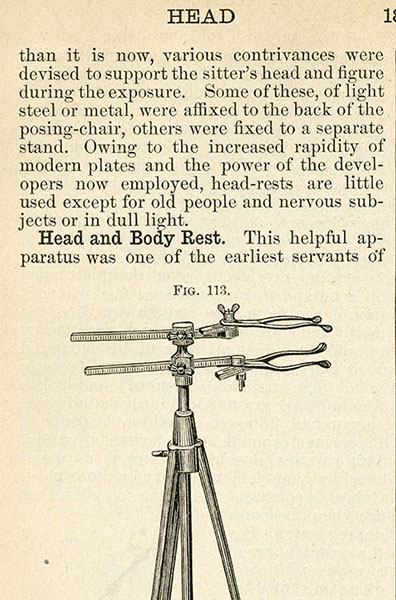

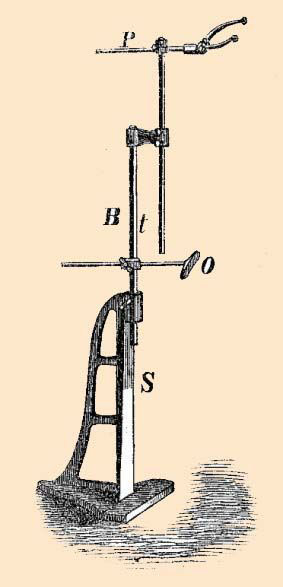

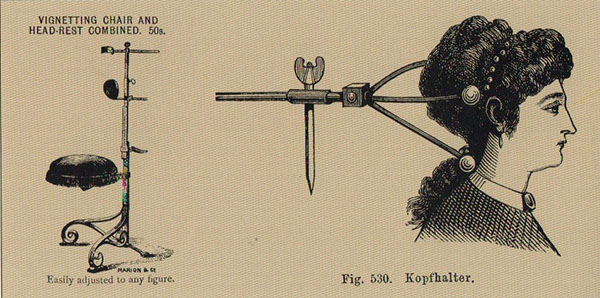

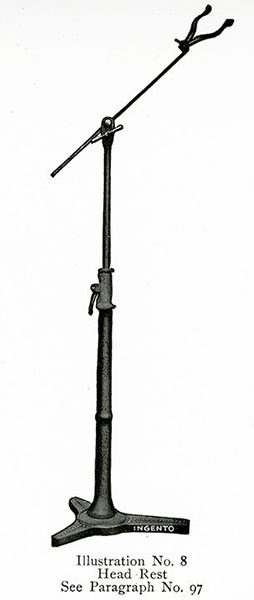

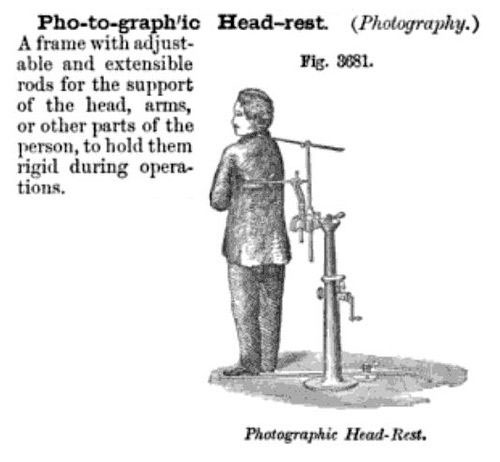

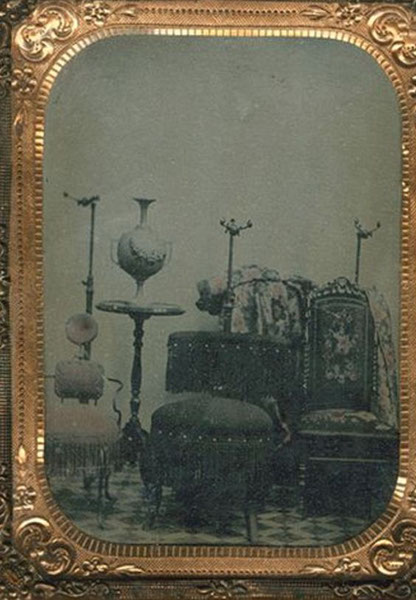

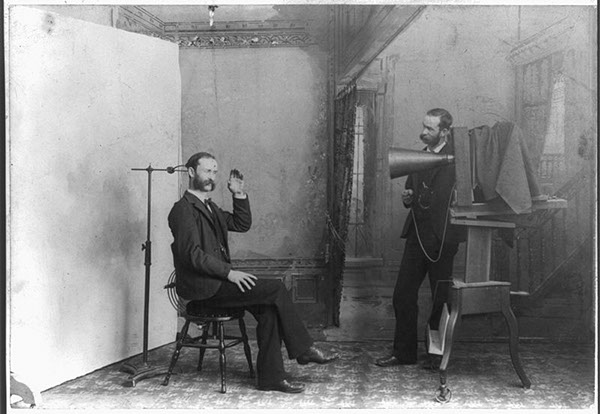

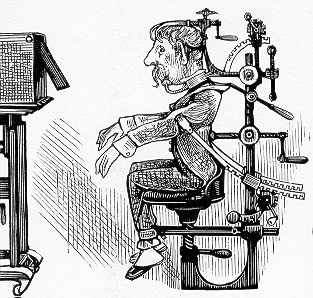

Certainly, in the early 1840s photographic technology (sensitivity of materials, speed of shutters) did not allow sure results and indeed the portrait on daguerreotype was for a long time described as a torment for the subject.

The satirical newspaper “Le Charivari” of August 30, 1839 wrote: “Do you want to make a portrait of your wife? Fix her head temporarily in an iron collar to obtain the necessary immobility…”

Facts were not that different:

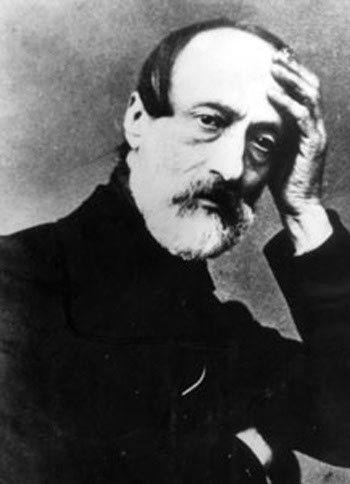

Samuel Morse, the American inventor had immediately imported the daguerreotype to New York to try to exploit it economically by making portraits, but for a long time he could not reduce below 10/20 minutes in the full sun, making it difficult to execute. John William Draper was also active in New York, and Robert Cornelius opened a studio in Philadelphia in 1840.

In the same year Voigtlander put on the market a “very bright” objective (today it would be equivalent to an f 3.6) and increased the sensitivity of the plates through a procedure called quick stuff which consisted in practice in making several successive sensitizing baths to the same plate alternating with iodine, bromine and chlorine, so that subsequent sensitisations would not chemically affect the previous baths. The shutter speed was reduced to 4 minutes and then to 25 seconds at the end of 1841. As a result of these technical improvements, daguerreotype studies spread around the world.

The Americans added automation and mass production: commentators of the time say that in the study of John Adams Whipple in Boston, a steam machine operated the polishers of copper plates, heated mercury, operated venting devices to refresh waiting customers and moved a rotating golden sun sign on the outside.

And the Americans won three out of five daguerreotypes medals at the Great Exhibition of Industrial Works held in London at the Crystal Palace in 1851.

The Crystal Palace at Hyde Park, London, American, 1851

New languages started to emerge in the representation of landscape:

Cincinnati waterfront (1848)

Ed Ruscha, Every Building on the Sunset Strip, 1966

https://www.openculture.com/2020/10/take-a-digital-drive-along-ed-ruschas-sunset-boulevard.html

The daguerreotype technique, however, was quickly giving way to new techniques that had fewer technical complications, faster and cheaper processes and that allowed to easily make copies of the original. The direct positive was slowly being substituted by the negative.

In 1856 at the annual exhibition of the Photographic Society of London 606 images were exhibited and of these only 3 were daguerreotypes.

Only two years earlier, in 1954, the State of Massachusetts officially declared that 403,626 daguerreotypes had been made in one year. Here the daguerreotype was a bit longer-lived but in 1864 the daguerreotype profession no longer appeared in the San Francisco telephone directory.

1841 – William Henry Fox Talbot – Calotype, development, latent image

In 1841 Talbot improved the photogenic drawing method and gave it the name of calotype (from the Greek kalòs, beautiful). Before that Talbot kept the sensitized paper (with salt and silver nitrate in the original recipe) exposed to light until he saw the image. Now he realized that a further bath after a shorter exposure made the action of light much more visible and effective. The process of development of the latent image became and still is the standard in film photography.

He dipped a translucent paper in silver nitrate and potassium iodide solutions. Silver iodide was then further sensitized with a bath in gallic acid and silver nitrate. Then he exposed the paper in the darkroom. After exposure he dipped the paper back into the same solution that acted as a developer.

He then fixed the negative with potassium bromide or with a warm solution of hyposulfite.

He produced a lot of views in Europe and England sending the negatives to his estate at Lacock Abbey where his wife and assistant Nicholas Henneman printed on a paper sensitized through the first photogenic process. In 1843 Talbot opened a printing laboratory in Reading (UK), the Talbotype Establishment. The printing speed of the new process was such that Tablot could produce thousands of copies to illustrate his work “The Pencil of Nature” containing 24 calotypes and annotations about them:

http://www.gutenberg.org/files/33447/33447-pdf.pdf

https://talbot.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/about-the-project-2/

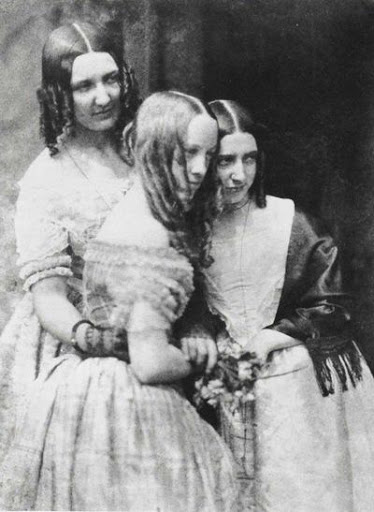

Hill & Adamson

The first artists to achieve artistic success with the calotype were David Octavius Hill and Robert Adamson who produced beautiful staged images with a delicacy that was well associated with the softness of the paper negative.

https://www.moma.org/artists/2648?=undefined&page=&direction=

https://gsaarchives.net/collections/index.php/ha-4-1b

http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/artists/1261/hill-adamson-scottish-active-1843-1848/

Gustave Le Gray waxed the paper before dipping it into sensitizing solutions to get brighter prints.

The French and English Fleets, Cherbourg, August 1858

Albumen silver print from glass negative; Mount: 21 in. × 26 3/4 in. (53.3 × 68 cm) Image: 11 13/16 in. × 16 in. (30 × 40.7 cm)

The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, Bequest of Maurice B. Sendak, 2013 (2013.159.37)

http://www.metmuseum.org/Collections/search-the-collections/306320

Louis Blanquart-Evrard in 1850 designed a printing paper that reduced the printing time of a copy to 6 – 15 seconds. He covered the paper with egg whites in which potassium bromide and acetic acid were dissolved. Once dry, it was agitated in a silver nitrate solution and re-dried. The prepared sheet was superimposed on the negative and exposed to the sun. His Imprimeriè Photographique by Lille was able to produce high runs of “Album photographique”.

His masterpiece was “Egypte, Nubie, Palestine, et Syrie” containing 122 photos of Maxime Du Camp, a scholar who had travelled to the Middle East between 1849 and 1852, along with Gustave Flaubert.

“I lost precious time in drawing the monuments or views that I wanted to remember,” explained Du Camp. “I drew slowly and in an incorrect manner. I understood that I needed a precision instrument to bring back images that would allow me to make exact reconstructions,”

Blanquart-Evrard also published calotypes made along the Nile by John B. Greene (°°°), Henri Le Secq (°°°), Charles Negre (°°°).

The latter photographed his friend Le Secq on the terrace of Notre Dame in 1851:

Even though the classic printing system was through contact, in this period the first solar machines for magnification appear:

“Jupiter” enlarger on the roof of Van Stavoren Studio, Nashville, Tennessee, 1866

1851 – Frederick Scott Archer – Collodion

Frederick Scott Archer used collodion and potassium iodide to impregnate a glass plate. Then, in darkness, he plunged it in a silver nitrate solution and the silver iodide sensitive to light was formed in the collodion.

The plate had to be exposed still humid and developed in pyrogallic acid and fixed before the collodion hardened (stabilizing the negatives).

That’s why the photographers had to take the lab with them:

1851 Mission Héliographique

In 1851, the Commission des Monuments Historiques, an agency of the French government, selected five photographers to make photographic surveys of the nation’s architectural patrimony. These Missions Héliographiques, as they were called, were intended to aid the Paris-based commission in determining the nature and urgency of the preservation and restoration of work required at historic sites throughout France.

The selected photographers—Édouard Baldus , Hippolyte Bayard, Gustave Le Gray , Henri Le Secq, and Auguste Mestral—were all members of the fledgling Société Héliographique, the first photographic society. Each was assigned a travel itinerary and detailed list of monuments. Baldus was sent south and east to photograph the Palace of Fontainebleau , the medieval churches of Lyon and other towns in the Rhône valley, and the Roman monuments of Provence, including the Pont du Gard, the triumphal arch at Orange, the Maison Carrée in Nîmes, and the amphitheater at Arles.

Gustave Le Gray, already recognized as a leading figure on both the technical and artistic fronts of French photography, was sent southwest, to the famed châteaux of the Loire Valley—Blois, Chambord, Amboise, and Chenonceaux, among others—to the small towns and Romanesque churches along the pilgrimage routes to Santiago de Compostela, and through the Dordogne. Le Gray traveled with Mestral and photographed sites on his old friend and protégé’s list, including the fortified town of Carcassonne (not yet “restored” by Viollet-le-Duc), Albi, Perpignan, Le Puy, Clermont-Ferrand, and other sites in south-central and central France. On occasion, the two worked hand-in-hand, for a few photographs are signed by both photographers.

Henri Le Secq was sent north and east to the great Gothic cathedrals of Reims, Laon, Troyes, and Strasbourg, among others. And Hippolyte Bayard, the only one of the five to have worked with glass—rather than paper—negatives (and thus, the only one whose negatives no longer survive), was sent west to towns in Brittany and Normandy, including Caen, Bayeux, and Rouen.

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/heli/hd_heli.htm

Google images Missions Héliographiques

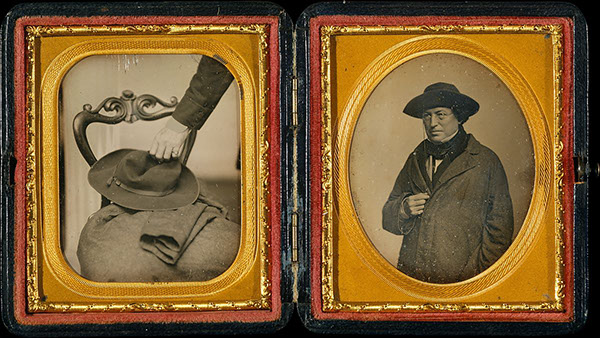

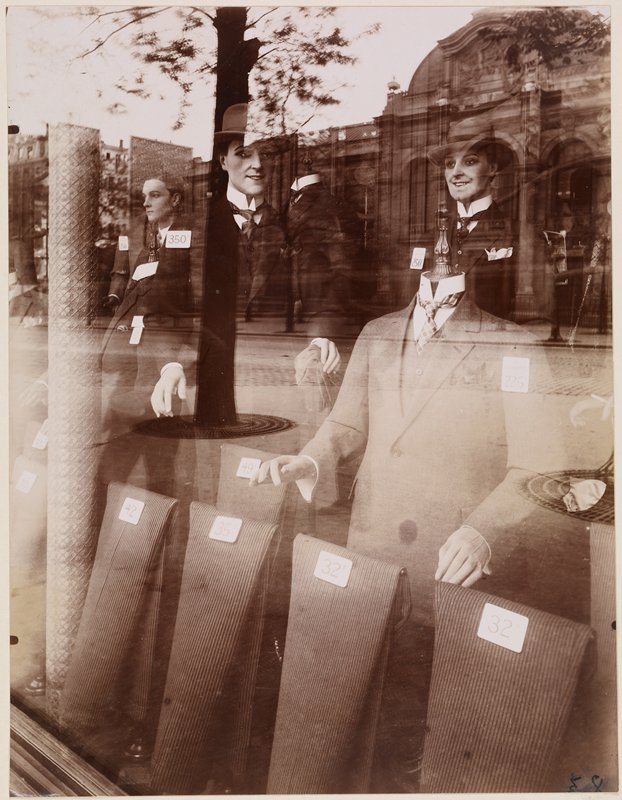

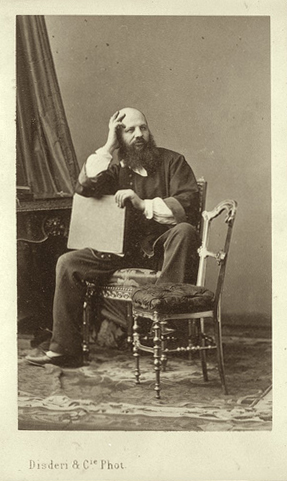

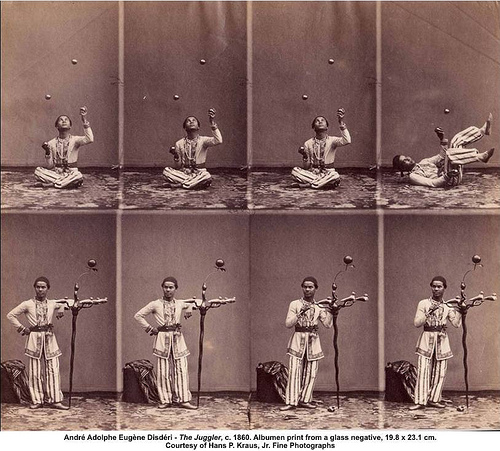

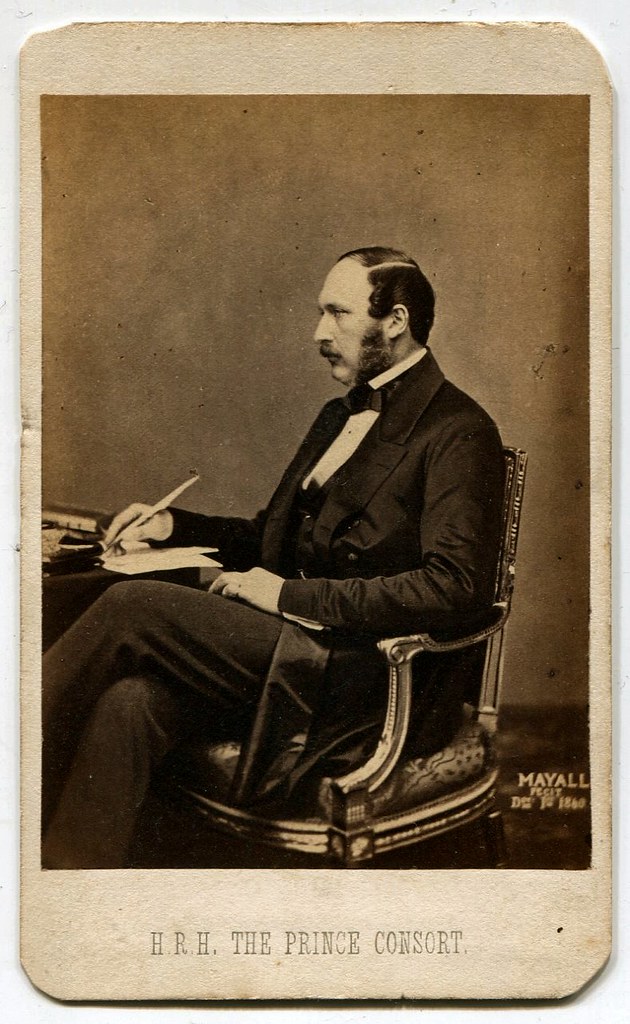

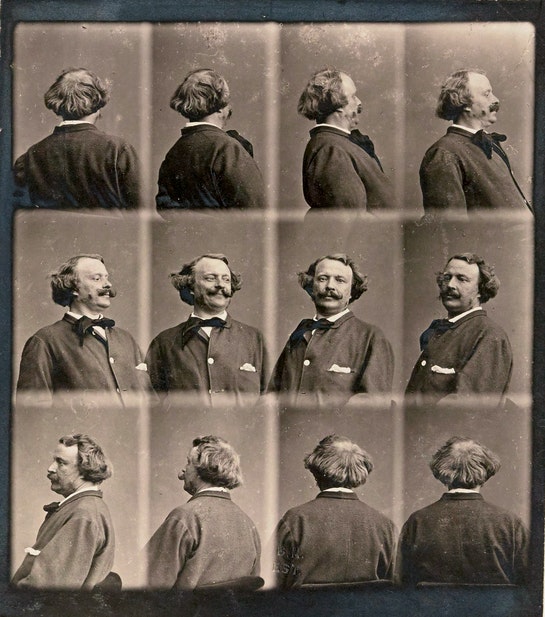

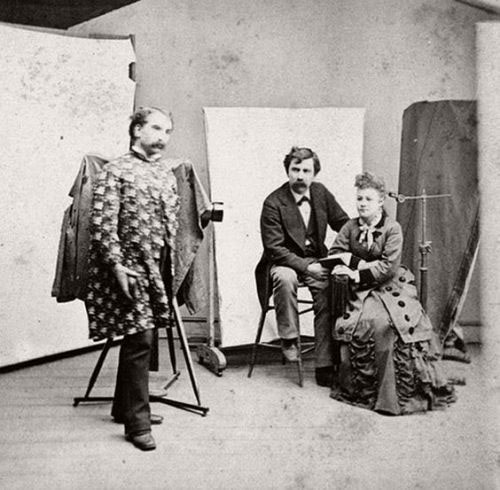

La Carte de visite

In 1854 a French photographer named Disderi introduced a method that would be called Carte-de-visite for its resemblance to business cards of that time.

He invented a camera with four lenses and a sliding plate holder. He was able to make 8 exposures on the same plate, to obtain 8 contact prints that were then cut out and glued on cardboard of 10×6 cm (just like business cards).

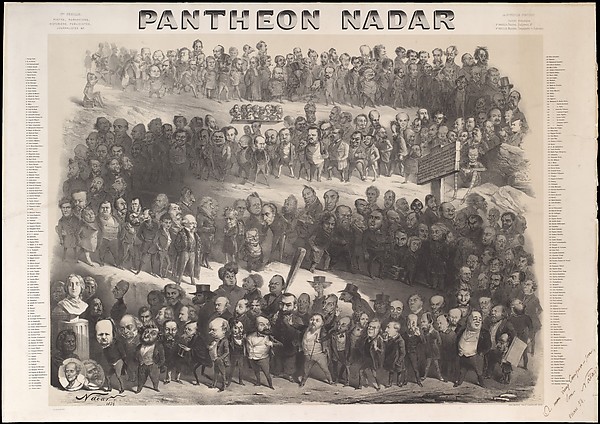

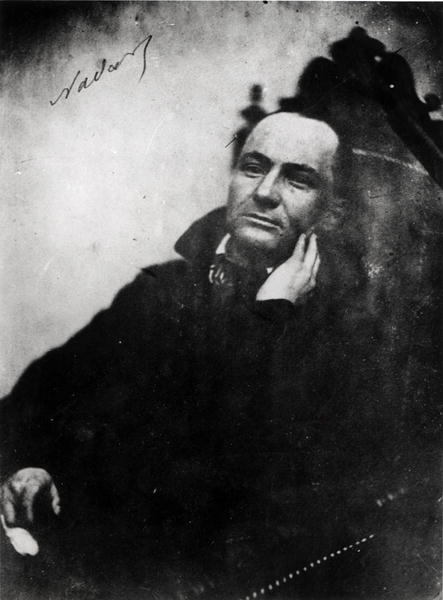

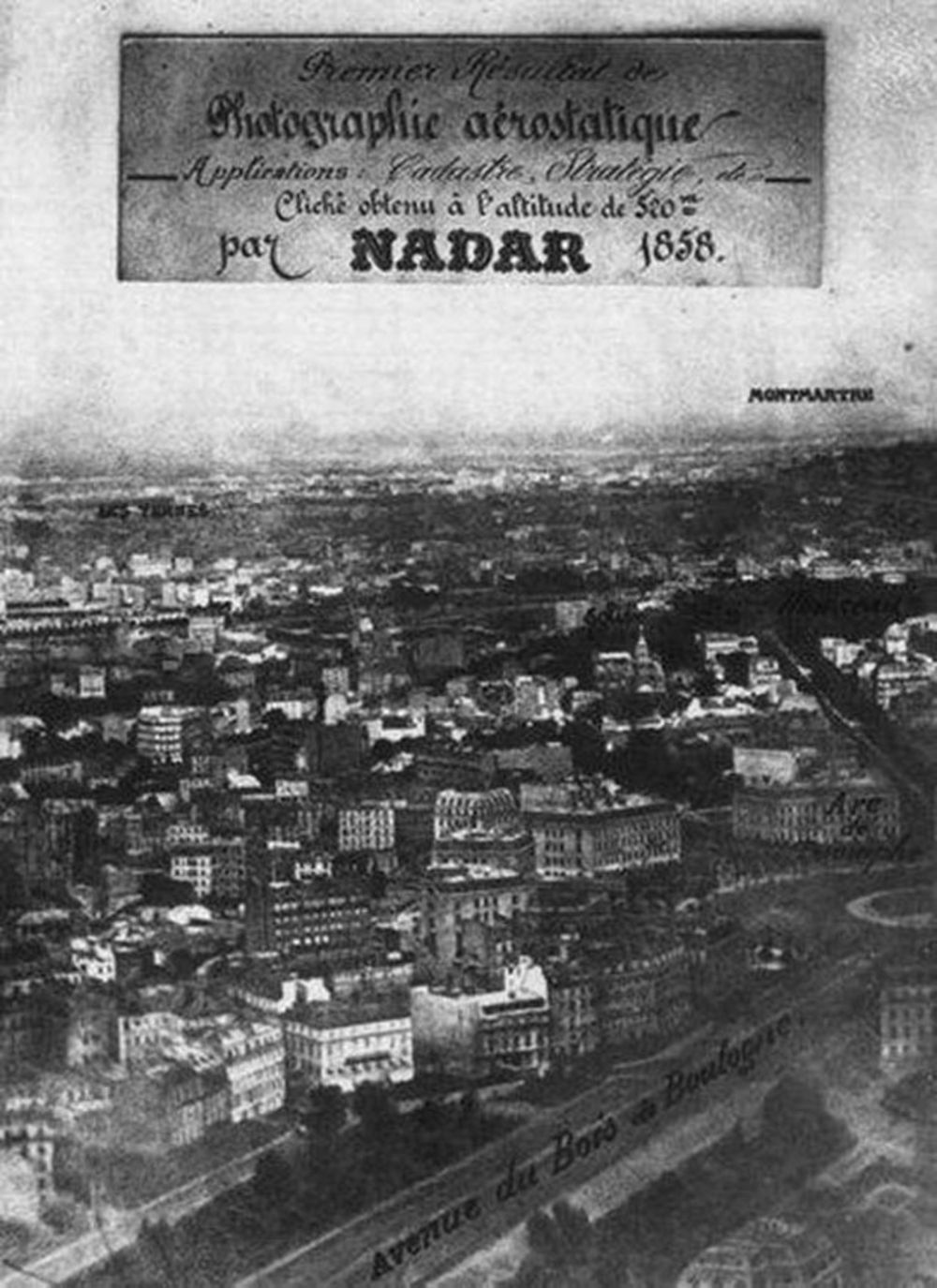

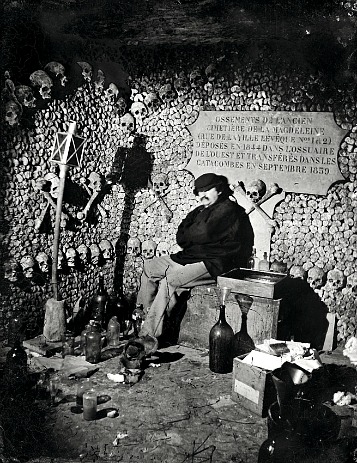

Nadar

https://publicdomainreview.org/collection/photographs-of-the-famous-by-felix-nadar

Artist active in the bohemian society in Paris in 1850. Friend of artists, writers and the whole XIXth century Paris intelligentia.

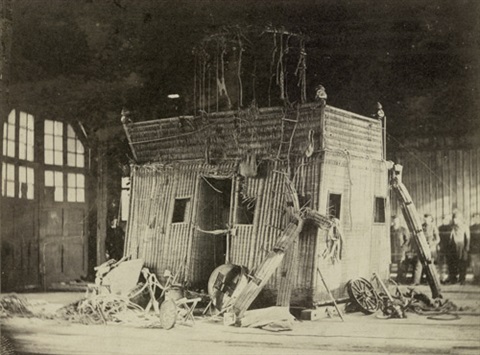

Le Geant

Catacombes artificial light

Collaborations

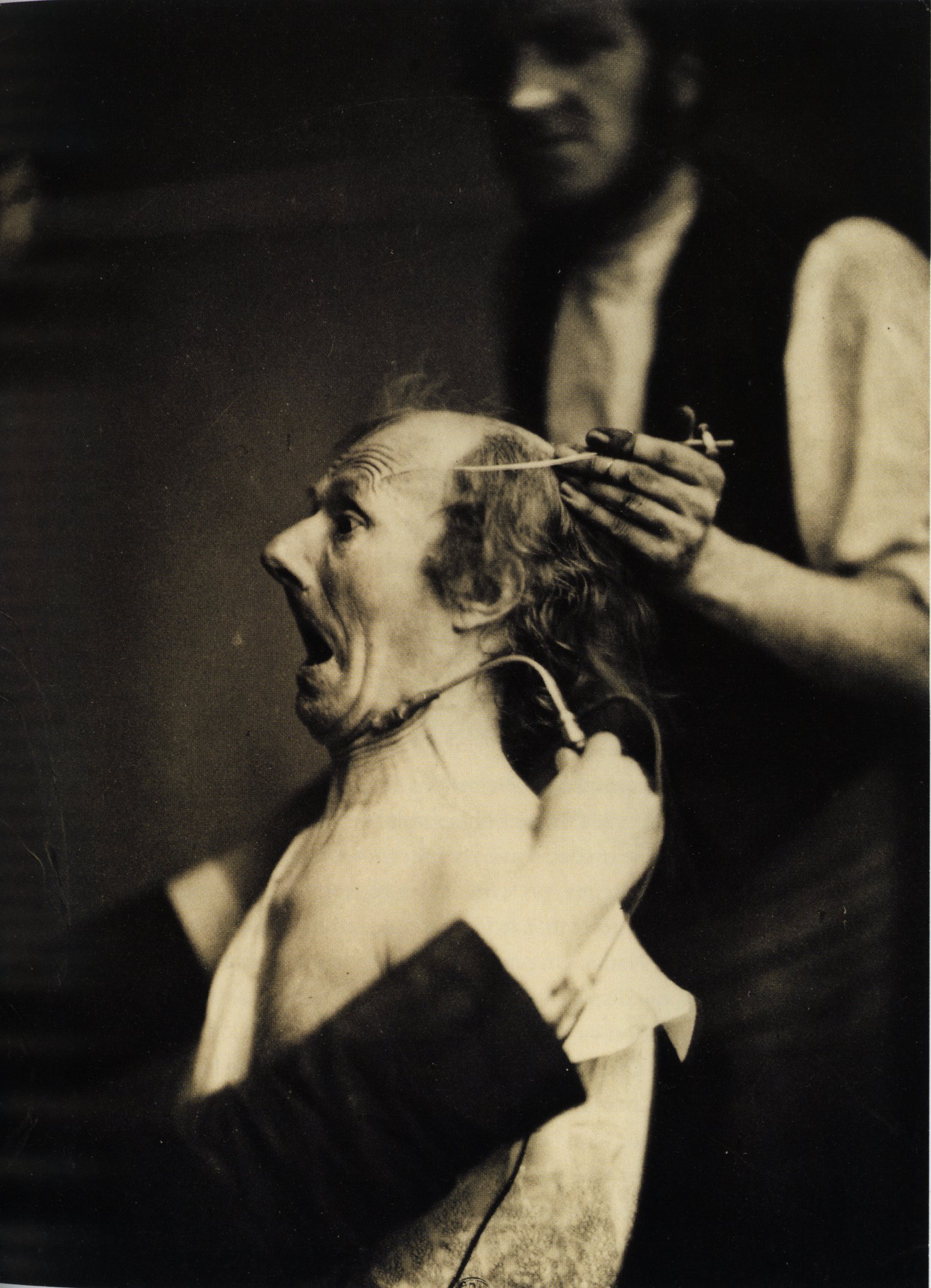

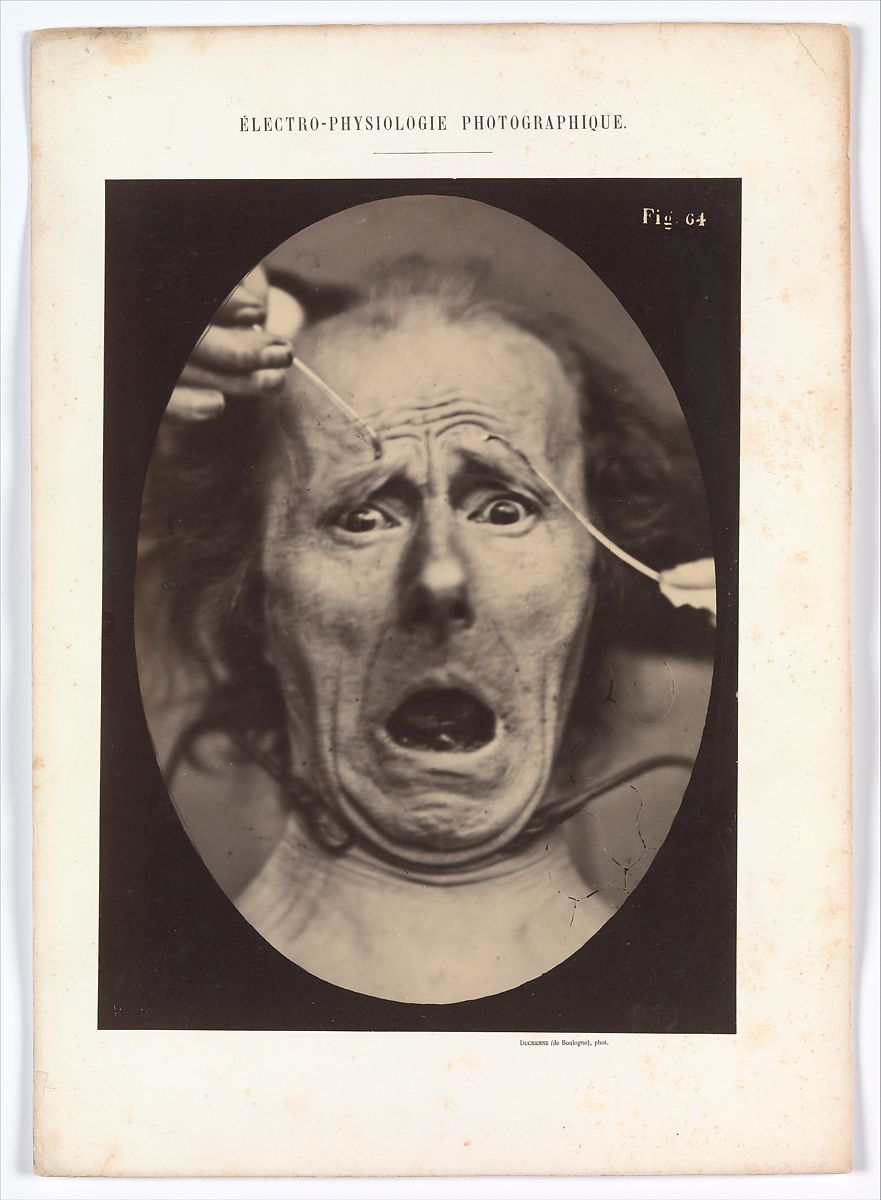

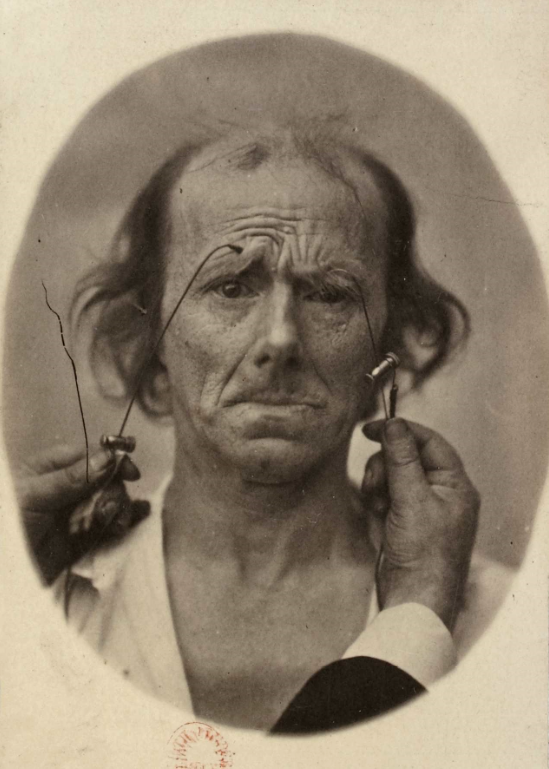

Mecanisme de La Physionomie Humaine: Ou, Analyse Electro-

“Artistic photography”

As the printing techniques developed, artists began to intervene more and more heavily on the negative and/or the print: “artistic photography”.

About 30 negatives, final print 78x40cm. Bought by Queen Victoria.

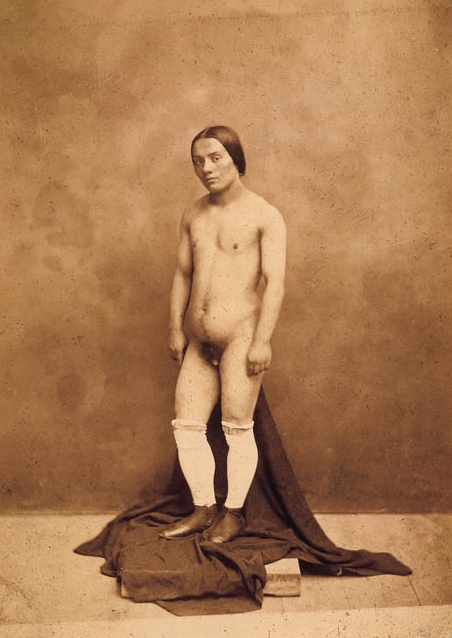

Rejlander. The expression of the emotions in man and animals, by Charles Darwin

Henry Peach Robinson

5 negatives

https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/283092

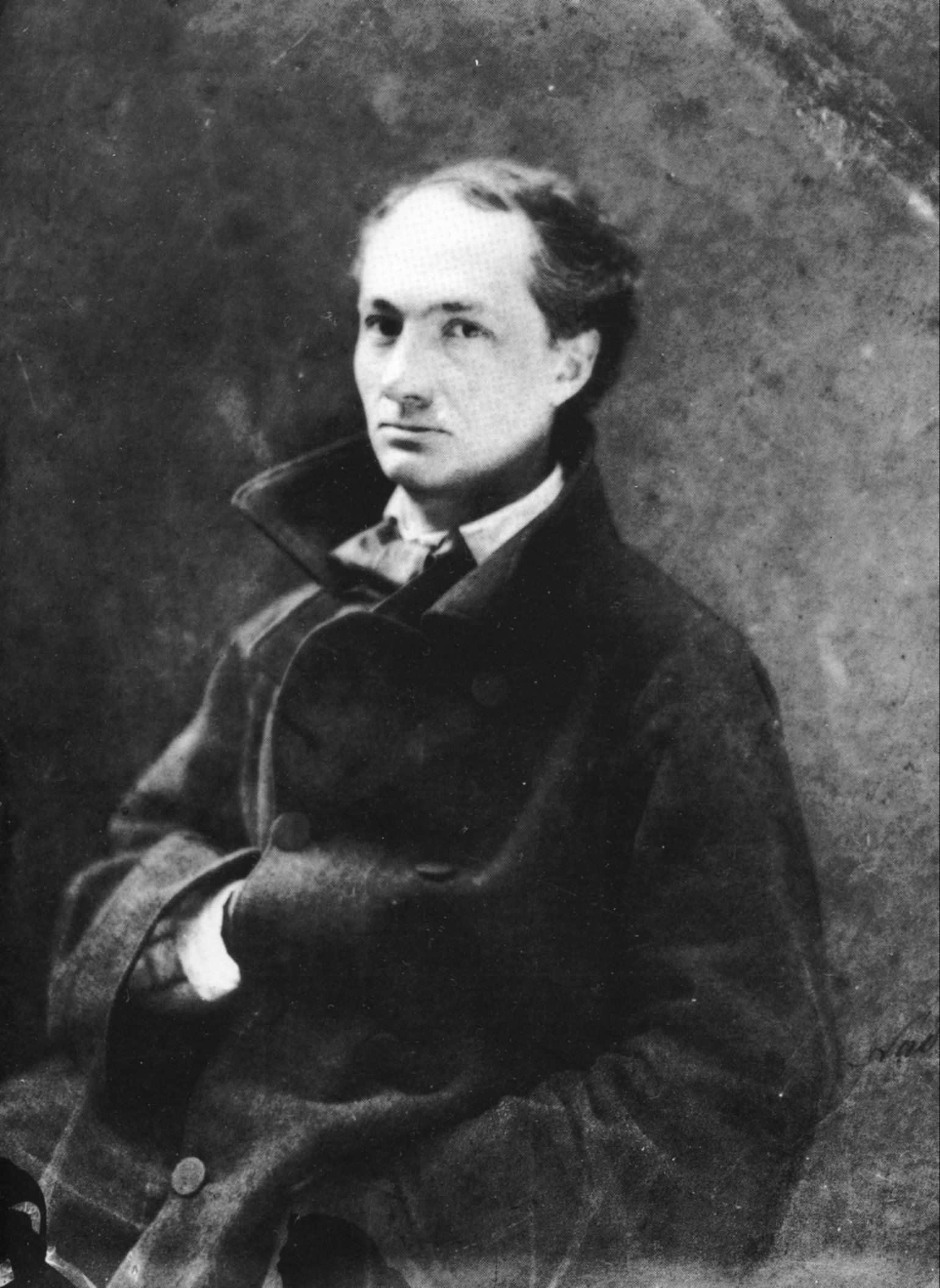

“but I am convinced that the ill-applied developments of photography, like all other purely material developments of progress, have contributed much to the impoverishment of the French artistic genius, which is already so scarce.

Poetry and progress are like two ambitious men who hate one another with an instinctive hatred, and when they meet upon the same road, one of them has to give place. If photography is allowed to supplement art in some of its functions, it will soon have supplanted or corrupted it altogether, thanks to the stupidity of the multitude which is its natural ally. It is time, then, for it to return to its true duty, which is to be the servant of the sciences and arts— but the very humble servant, like printing or shorthand, which have neither created nor supplemented literature. Let it hasten to enrich the tourist’s album and restore to his eye the precision which his memory may lack; let it adorn the naturalist’s library, and enlarge microscopic animals; in short, let it be the secretary and clerk of whoever needs an absolute factual exactitude in his profession—up to that point nothing could be better. Let it rescue from oblivion those tumbling ruins, those books, prints and manuscripts which time is devouring, precious things whose form is dissolving and which demand a place in the archives of our memory—— it will be thanked and applauded. But if it be allowed to encroach upon the domain of the impalpable and the imaginary, upon anything whose value depends solely upon the addition of something of a man’s soul, then it will be so much the worse for us!”

(Charles Baudelaire, Révue Française, Paris, July 1859)

Letter of Rejlander to Henry Peach Robinson:

I am tired of photography-for-the-public, particularly composite photos, for there can be no gain and there is no honor, only cavil and misrepresentation. The next exhibition must only contain ivy’d ruins and landscapes for ever — besides portraits.”

It was the beginning of pictorialist movements in photography, which alternated in the history of the medium (and still alternate) with more documentary approaches that prefer to stick to a faithful representation of reality.

War

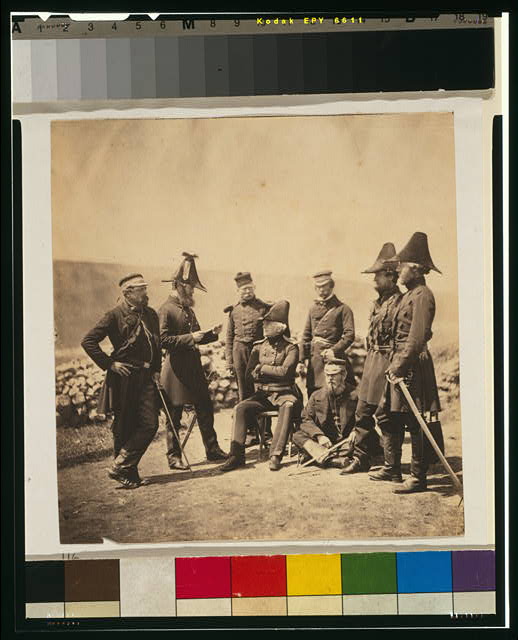

The first war photography reportage is signed by Roger Fenton. One of the founders of the Photographic Society of London, he was commissioned by Queen Victoria to photograph the family and the royal house and later became the official photographer of the British Museum.

He was commissioned by prints merchants Thomas Agnew & Sons to photograph the Crimean War. As he used the wet collodion, Fenton equipped a photographic van with 700 glass plates and the rest of the photographic material.

James Robertson riprese la caduta di Sebastopoli e fu poi inviato embedded con l’esercito della regina in India per fotografare le operazioni militari per domare le rivolte del Bengal. Lì gli fa da assistente suo cognato Felice Beato e insieme fotograferanno l’assedio di Lucknow e la Seconda Guerra dell’Oppio.

After the war Beato continued his journey to China and Japan where he documented the local rural life and customs.

A similar work was carried out later (at the turn of 1900) by Edward Curtis with the Native Americans. Both iconographies heavily influenced literary and cinematic production on the Far East and the Far West to this day.

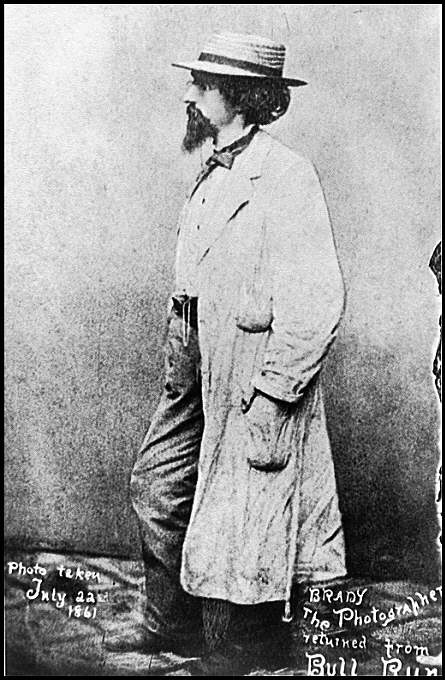

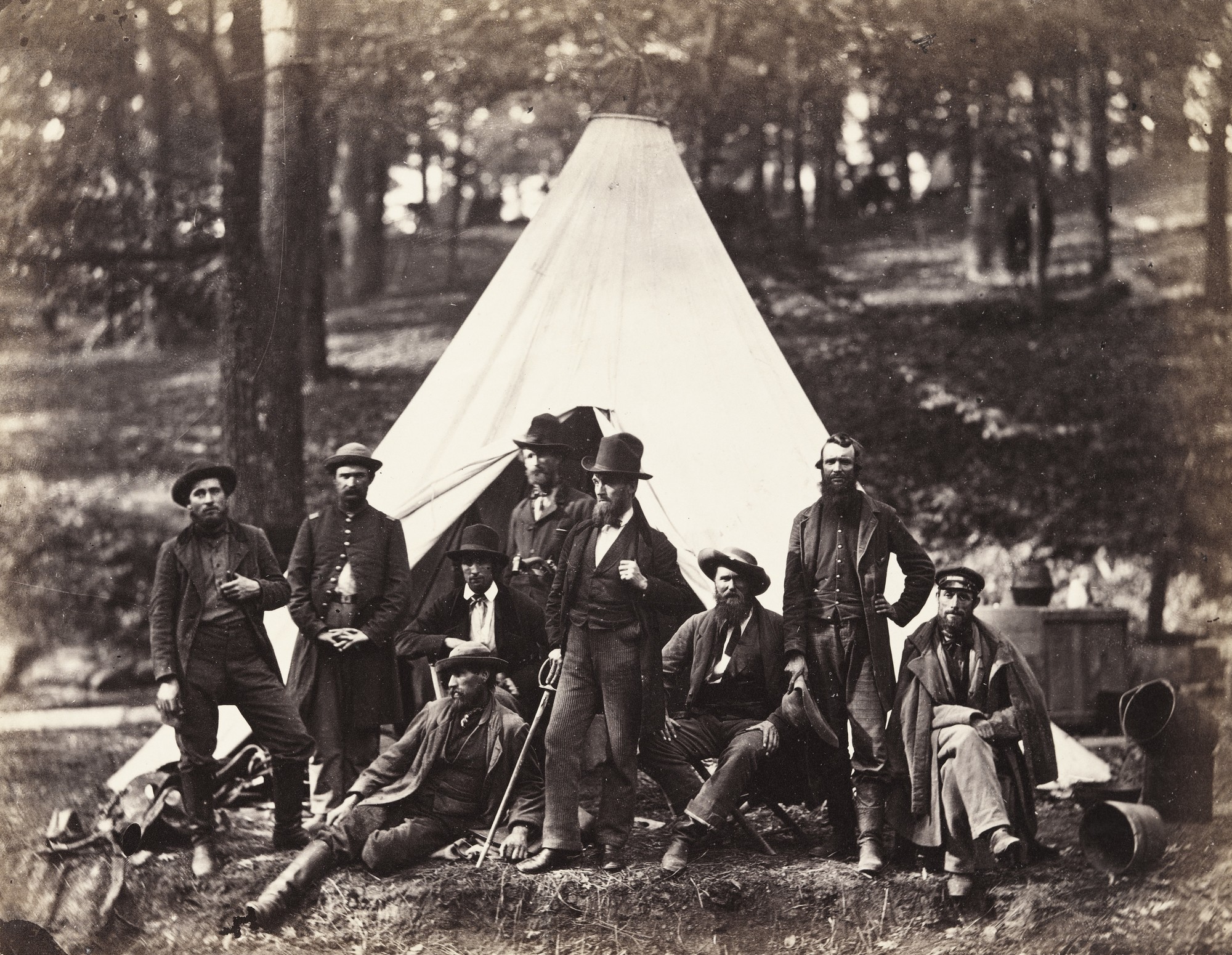

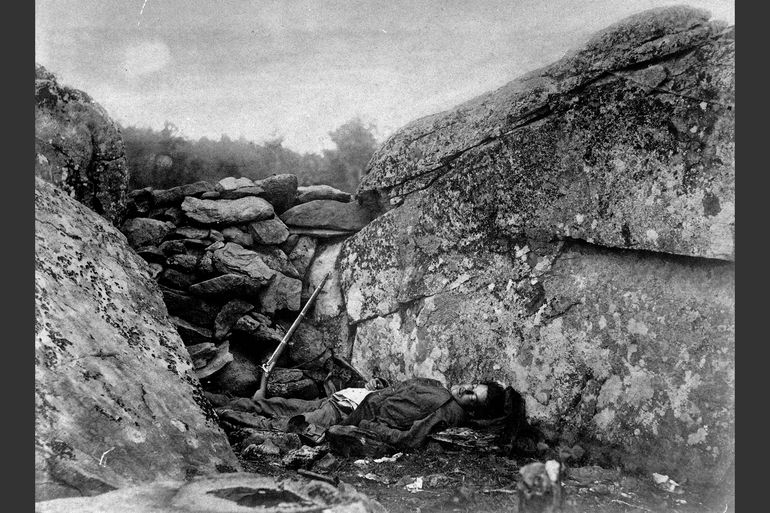

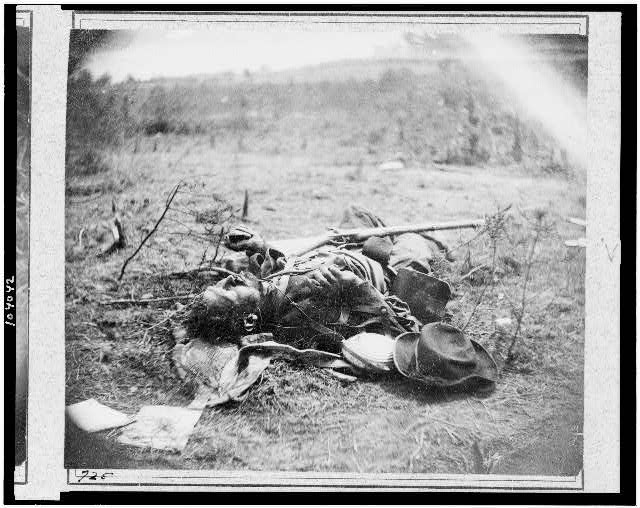

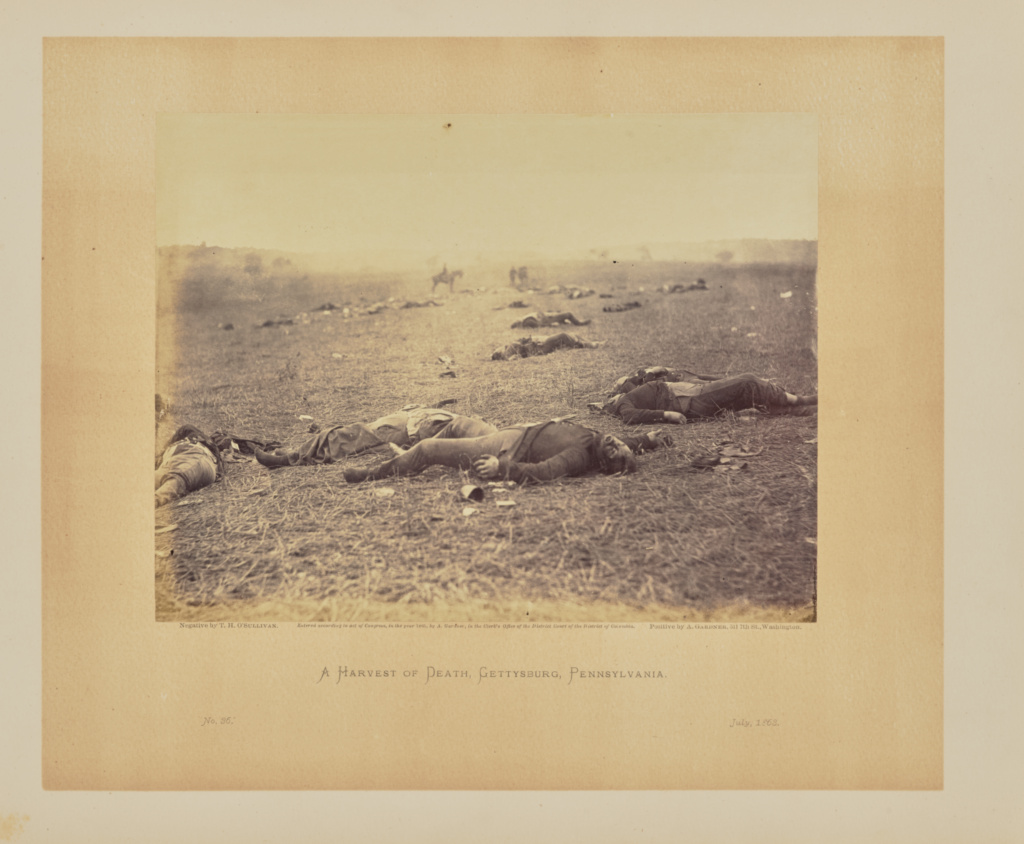

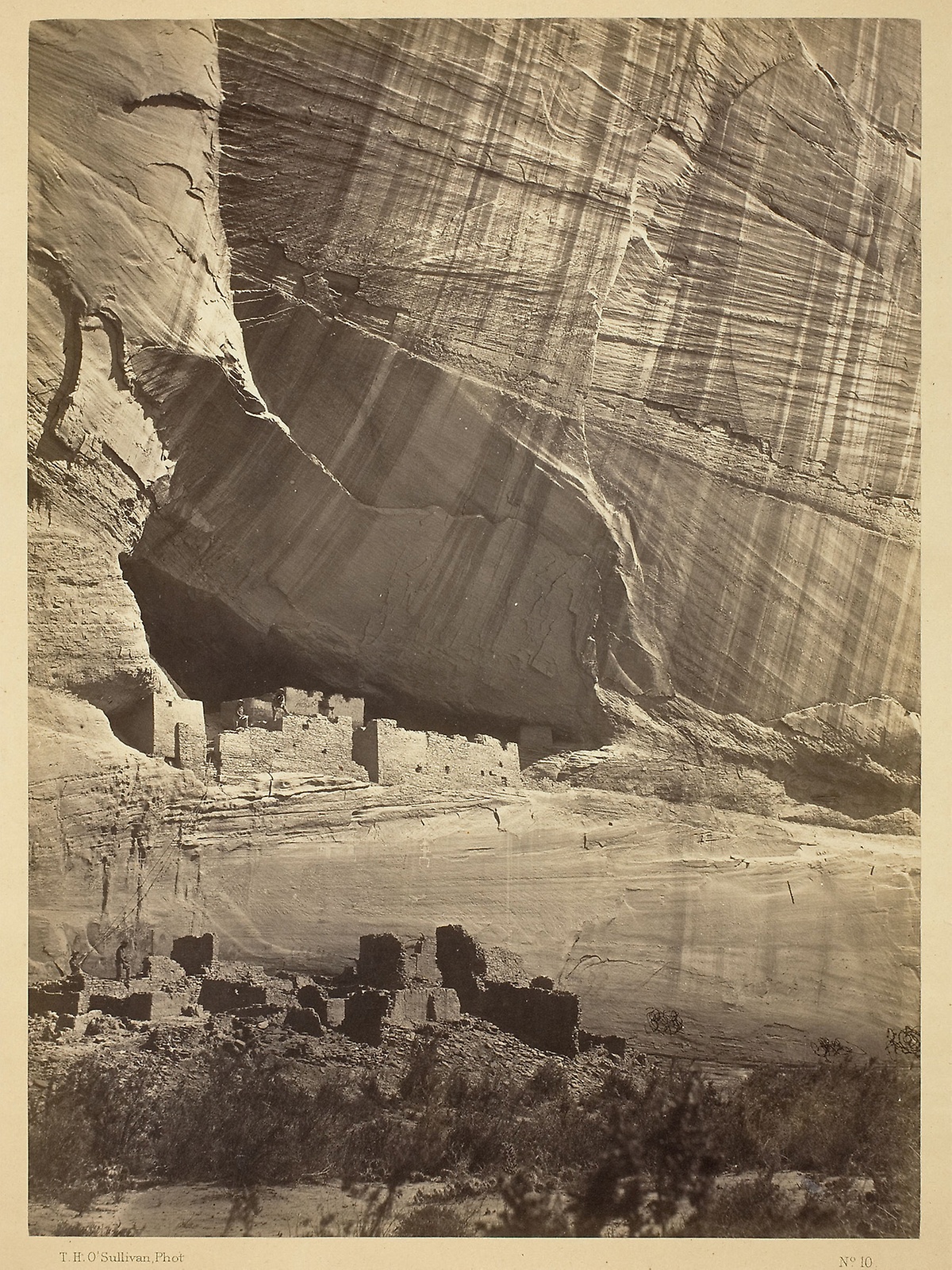

In 1861, the American Civil War broke out. Brady (the daguerreotyper) organized a group of photographers to set out in the quest to photograph the war. His team included Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan.

Exploration and progress

Many Civil War photographers later joined the army’s engineers engaged in paramilitary expeditions that later became official geographical surveys carried out for the United States government.

Fenton, Robertson, Beato and other early times war photographers had showed that images could be at great service of politics and empire.

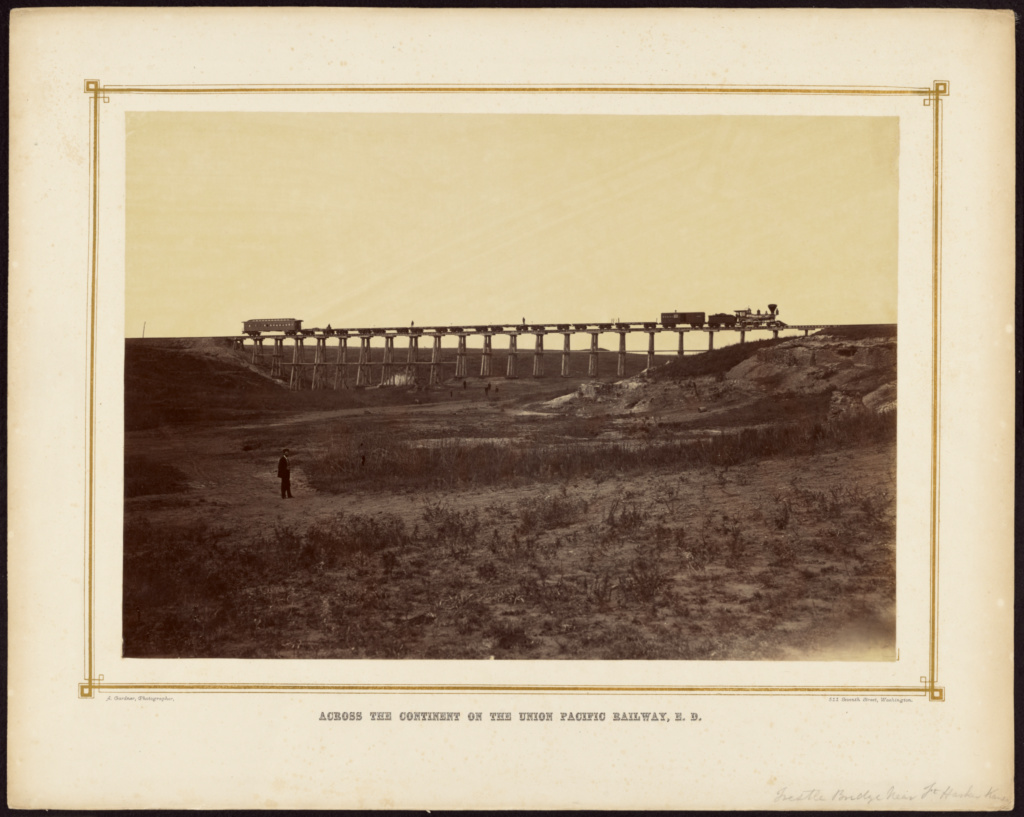

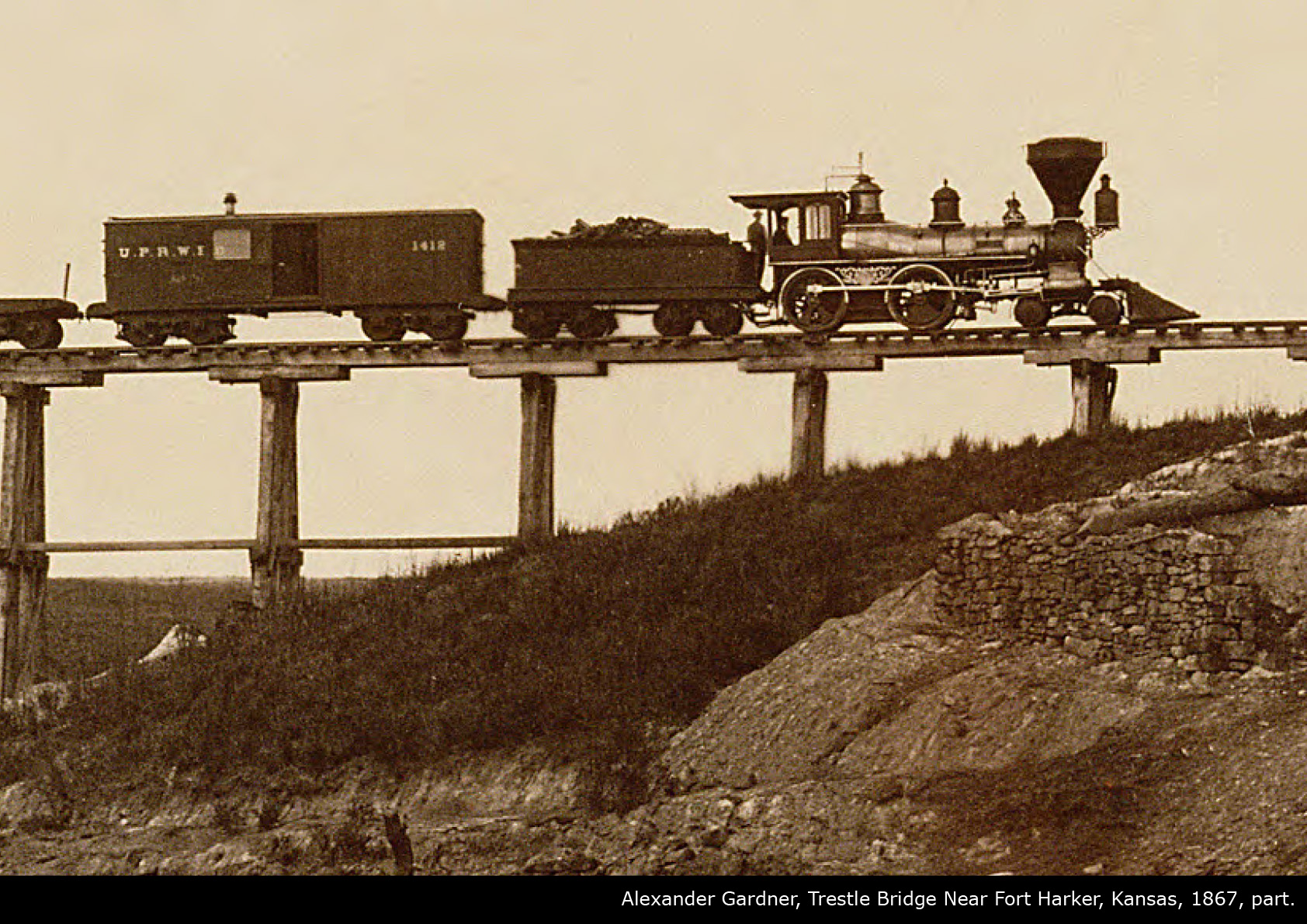

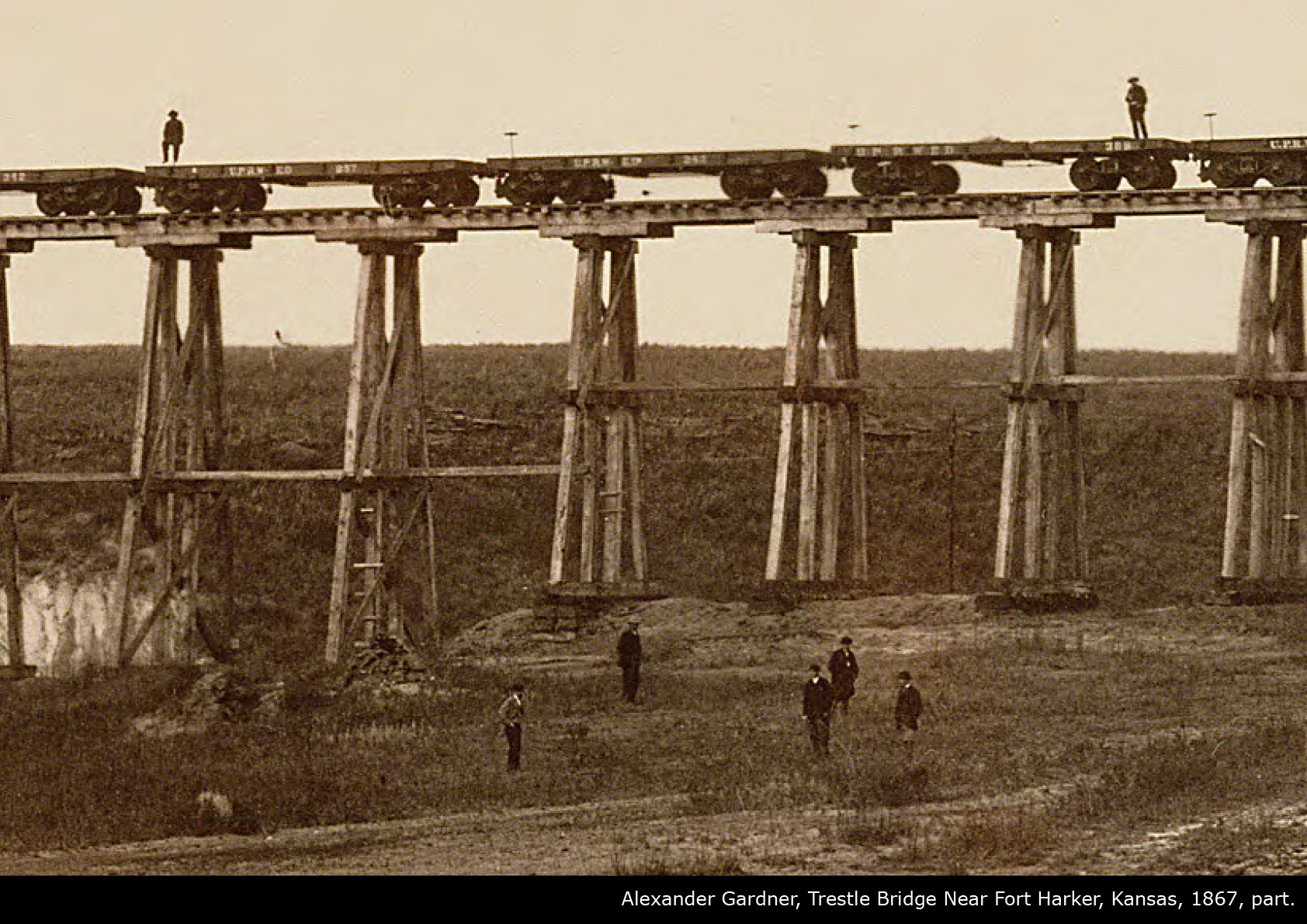

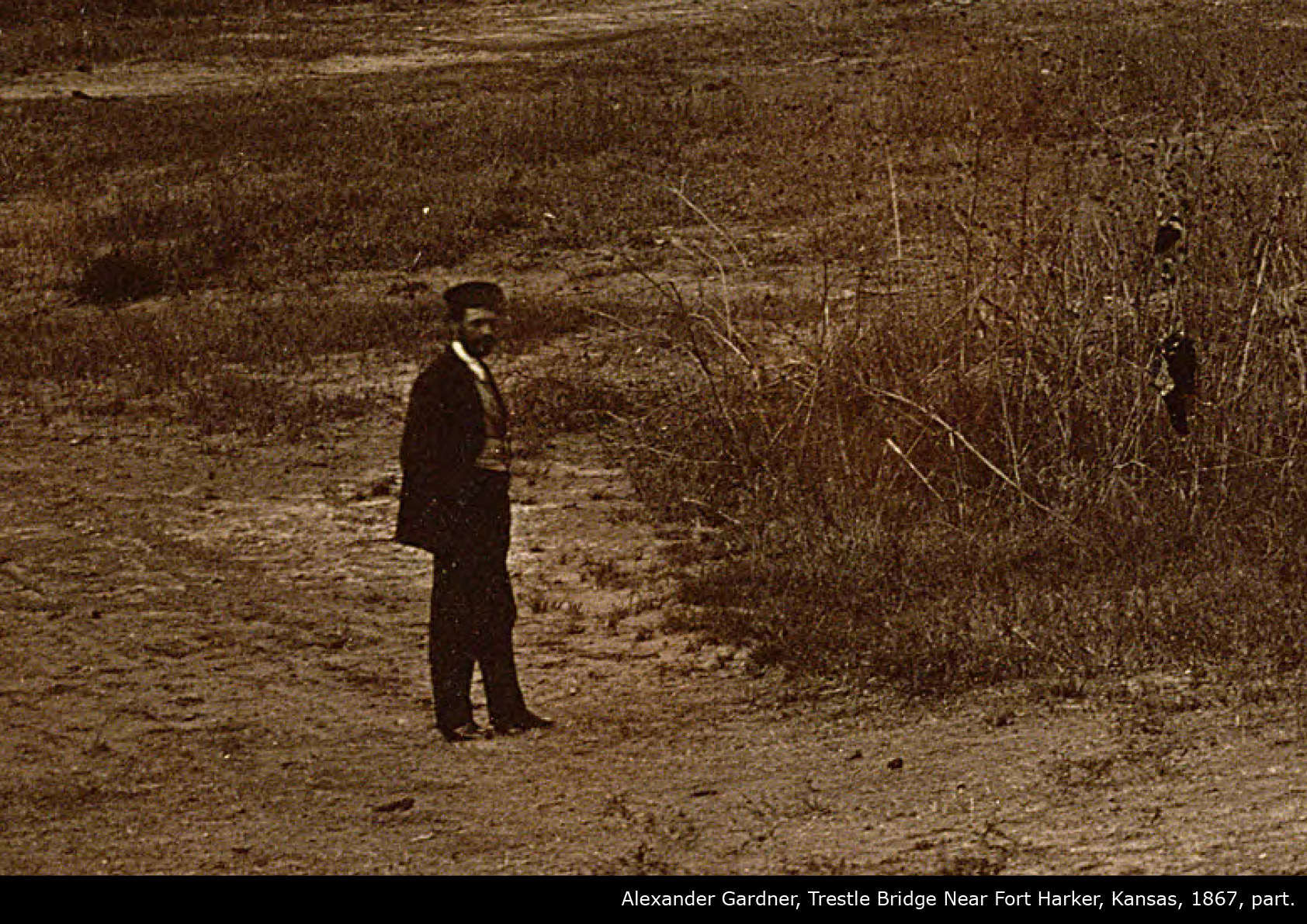

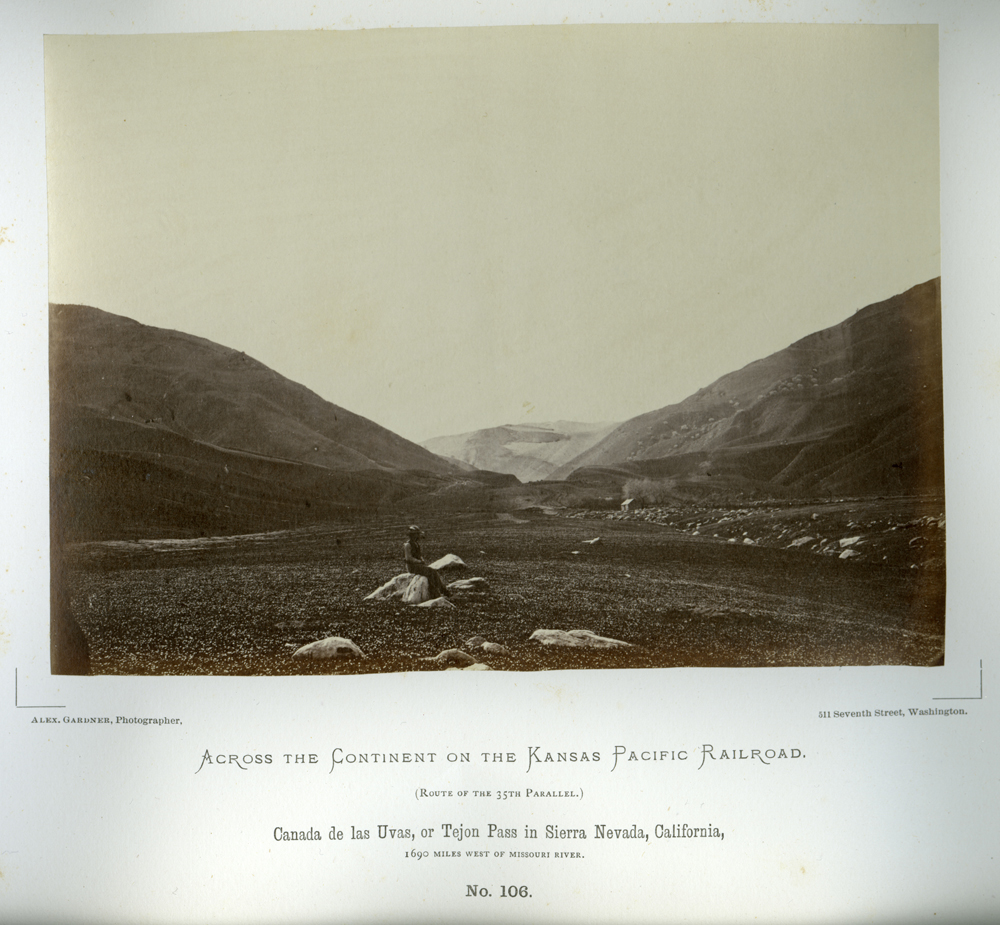

Alexander Gardner followed the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad to continue along a southwest track through Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona to the Sierra Nevada.

Raiway and photography embodied the same spirit of XIXth century progress. They were a conseguenze and a symbol of it. The be one of the first heading west and to pose for the photographer were two ways to be feel modern and be part of that incredible human Progress.

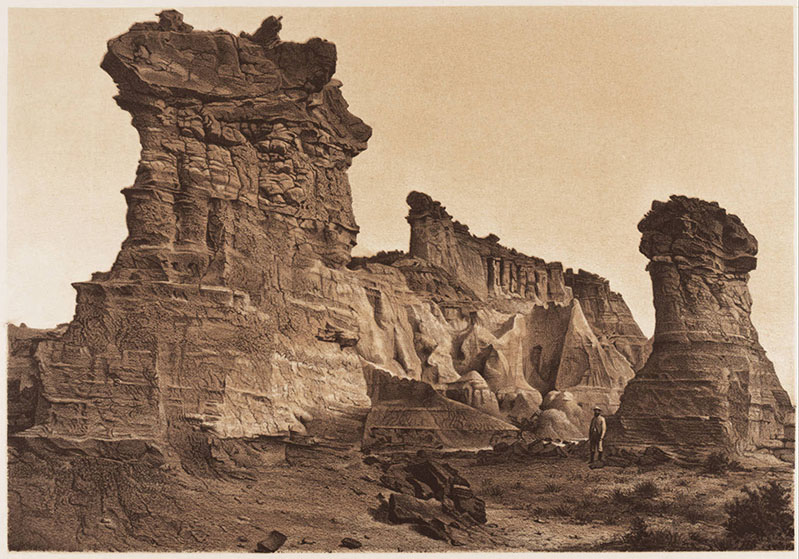

Surveys

Spedizione di Clarence King al 40° parallelo.

Spedizione di Clarence King al 40° parallelo.

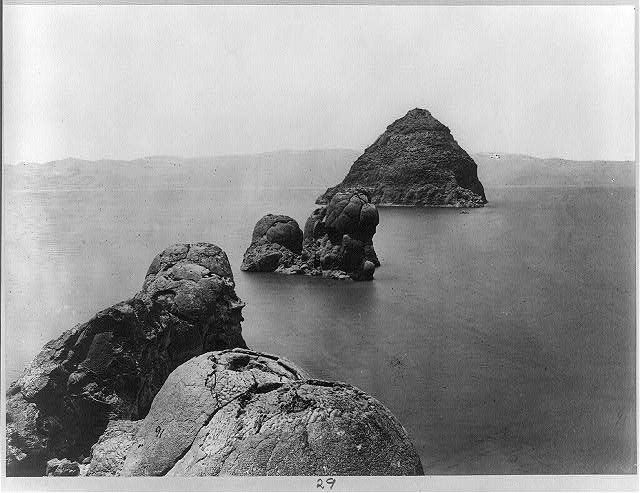

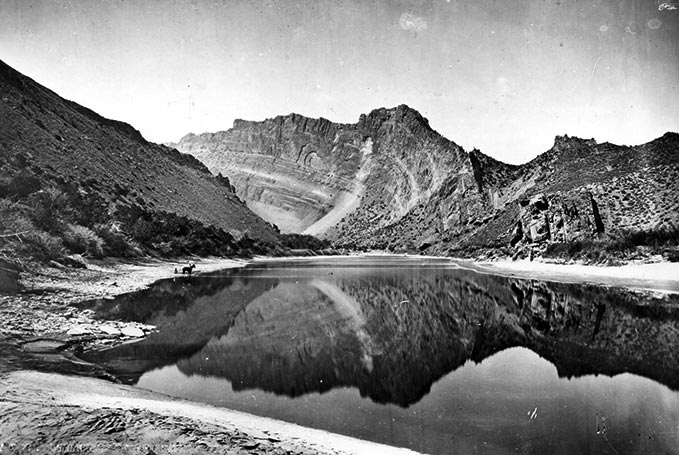

George Wheeler’s expedition west of the 100° meridian.

Geoplogical and geographical survey in Arizona 1873

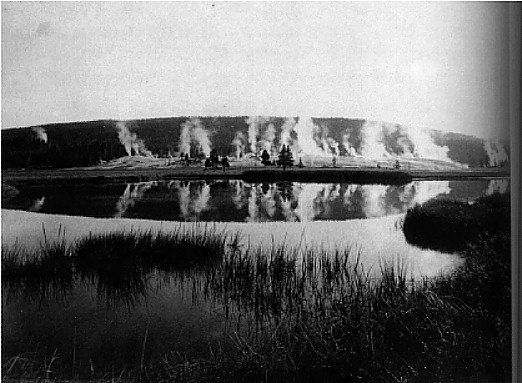

the beehive group of geysers, Yellowstone Park, 1872 Hayden Geological and Geographical expedition

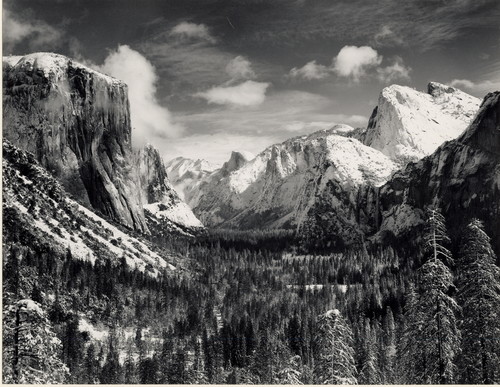

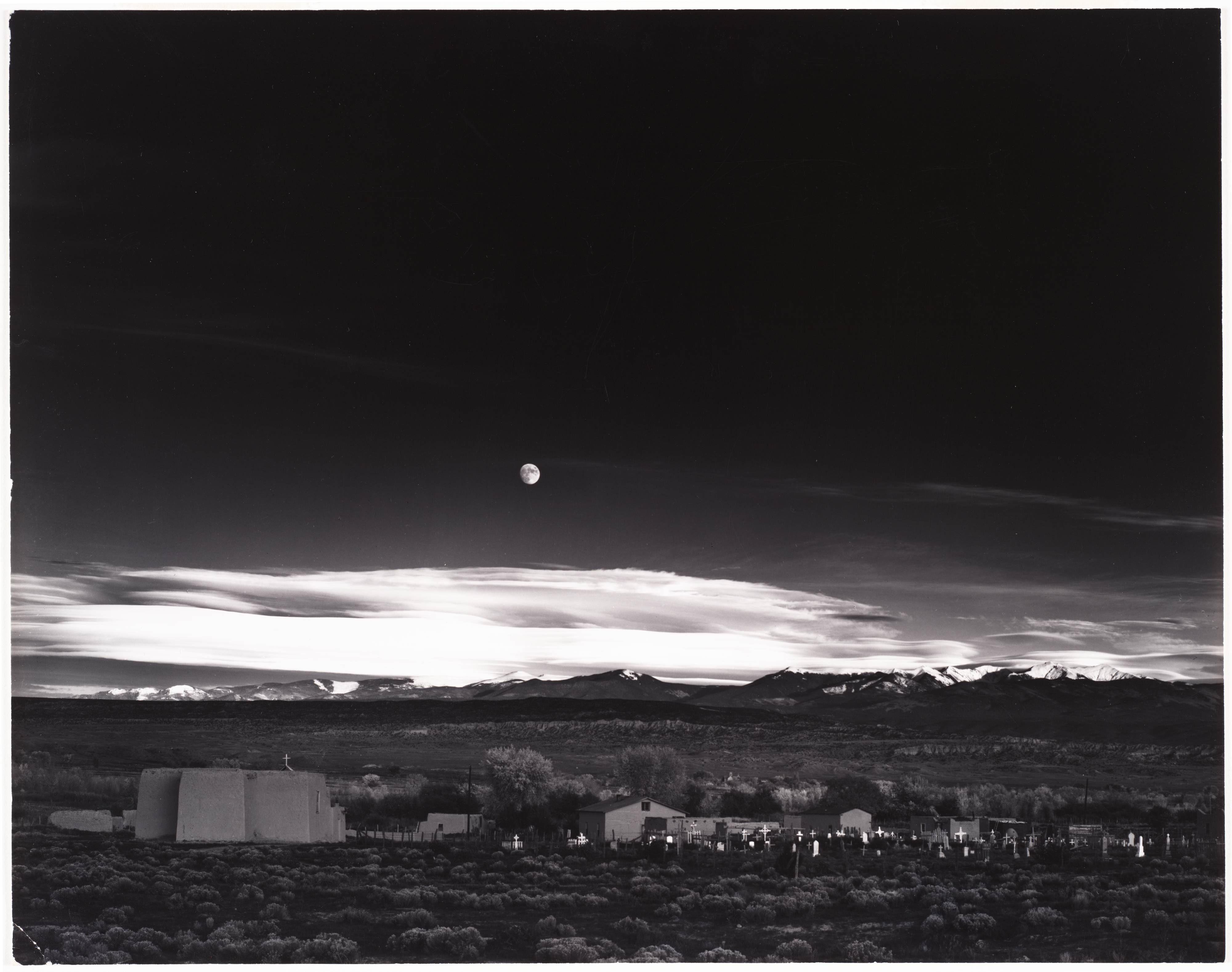

Summit of Yupiter Terraces, 1871.

Hayden Geological and Geographical expedition

Rocky Mountains

assistants

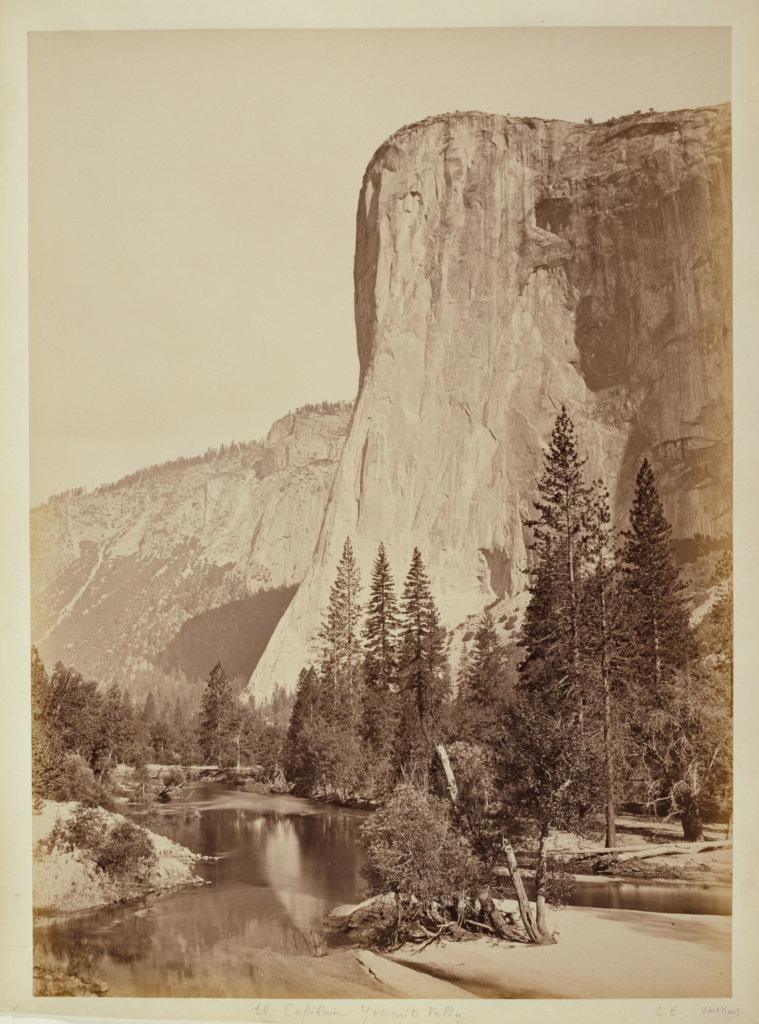

El Capitan, Yosemite, 1865

Yosemite, 1865

Movement

The first artists experimenting with fast shutters were George Washington Wilson and Edward Anthony.

Oliver Wendell Holmes, a scientist who studied the human movement, wrote in the Atlantic Monthly that the movements of people in those images were different from how they were conventionally represented in painting until then. He asked illustrator Felix Darley to draw those figures.

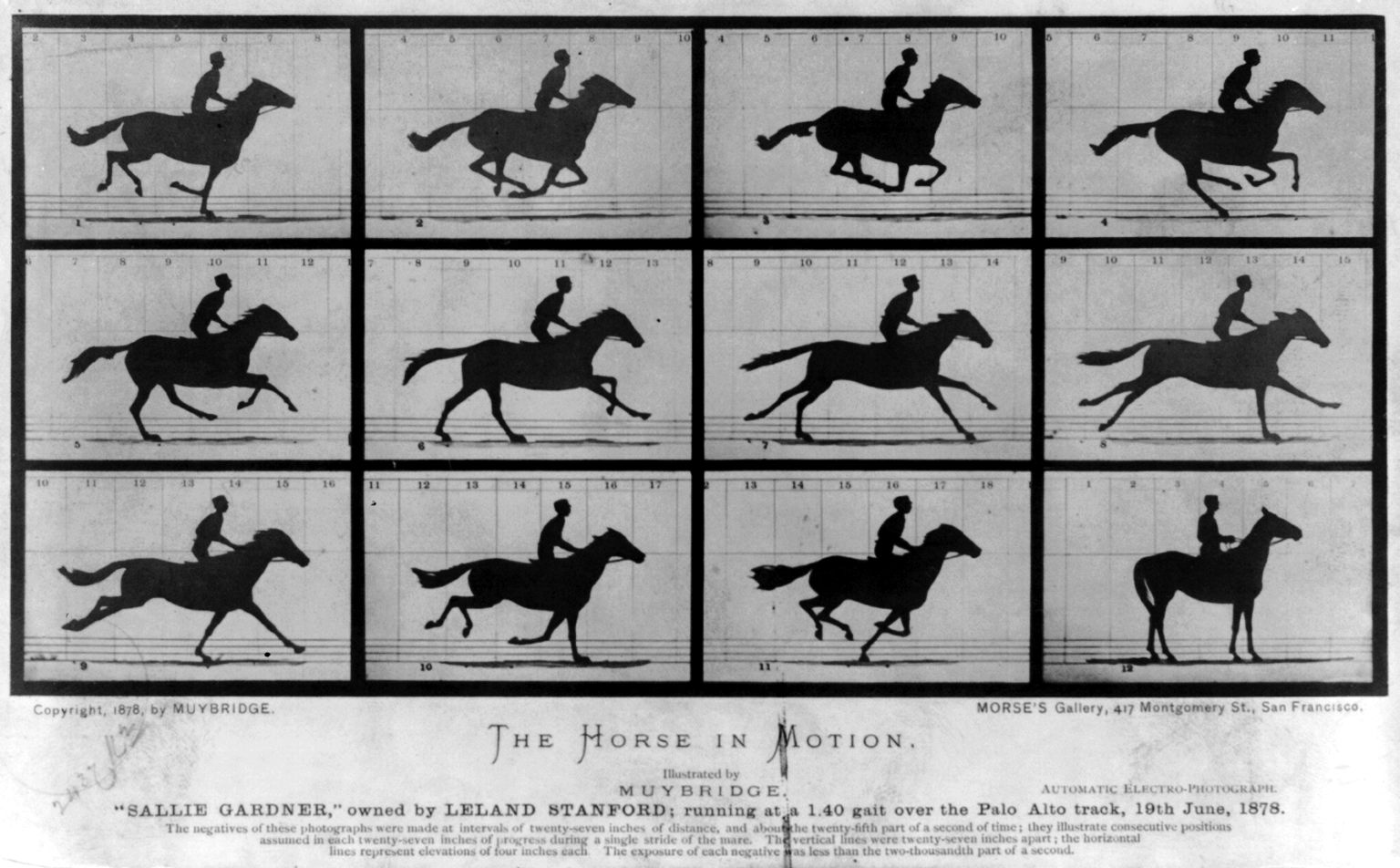

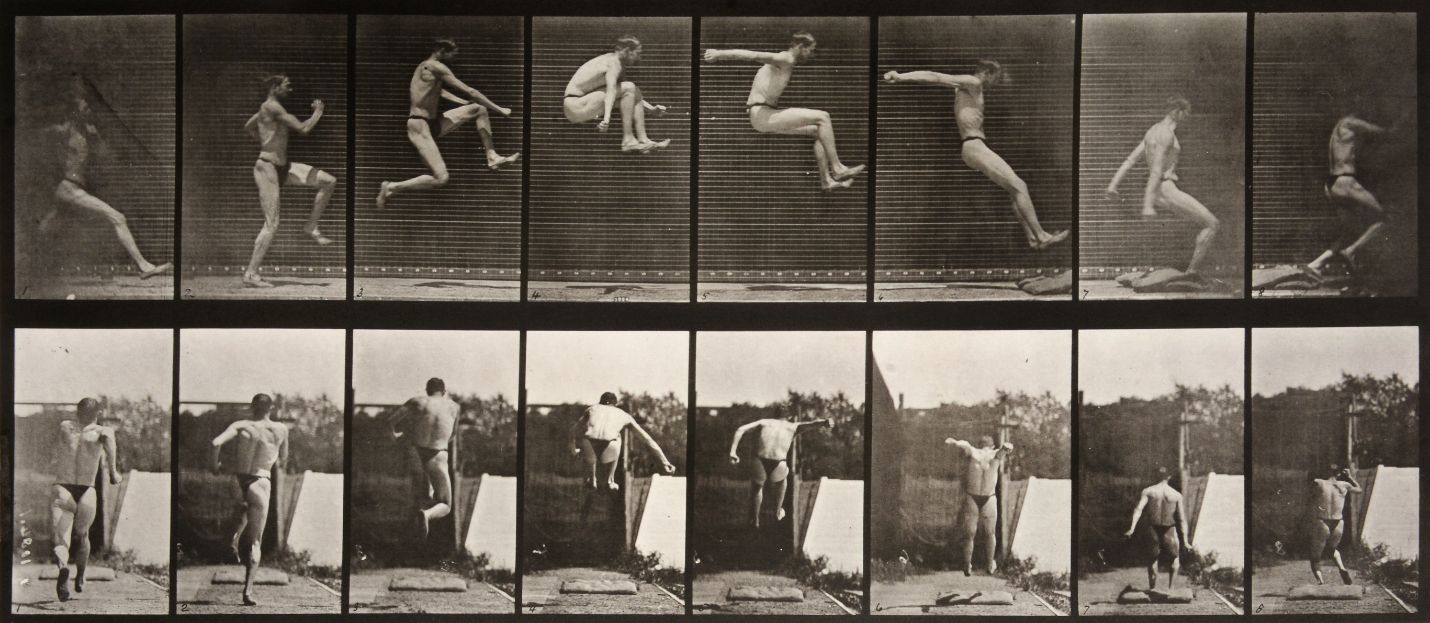

A decade later Edward Muybridge revolutionized this field of study with his photographs.

Lelan Stanford, a wealthy former governor of California, wanted to show his most famous trotter horse Occident to his distant friends. A friend suggested to ask for Muybridge, then known for his views of the Yosemite Valley, as in 1869 he invented one of the first shutters.

A journalist from the San Francisco magazine “Alta” wrote:

“All the sheets in the neighborhood of the stable were procured to make a white ground to reflect the object, and “Occident” was after a while trained to go over the white cloth without flinching; then came the question how could an impression be transfixed of a body moving at the rate of thirty-eight feet to the second. The first experiment of opening and closing the camera on the first day left no result; the second day, with increased velocity in opening and closing, a shadow was caught. On the third day, Mr. Muybridge, having studied the matter thoroughly, contrived to have two boards slip past each other by touching a spring, and in so doing to leave an eighth of an inch opening for the five-hundredth part of a second, as the horse passed, and by an arrangement of double lenses, crossed, secured a negative that shows “Occident” in full motion – a perfect likeness of the celebrated horse”.

https://www.amusingplanet.com/2019/06/the-galloping-horse-problem-and-worlds.html

Muybridge’s immense work (about 30,000 negatives in about a year from 1884 to 1885) was published in 781 plates sold in eleven volumes titled Animal Locomotion (1887).

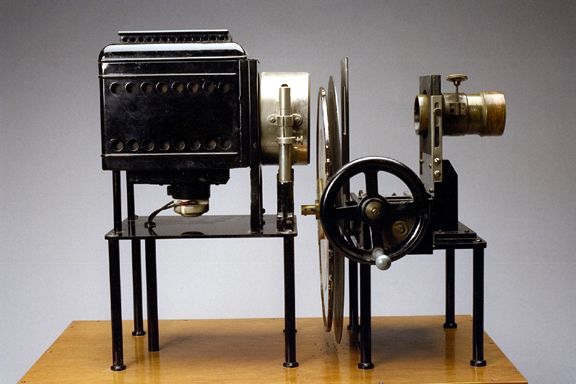

Muybridge used for the projection an instrument he called zoopraxiscope based on a popular toy called a zoetrope.

The invention of cinema directly followed this research. Brothers Louis and August Lumiere presented their first Cinematographe in 1895.

In the same years the first flash lights were invented.

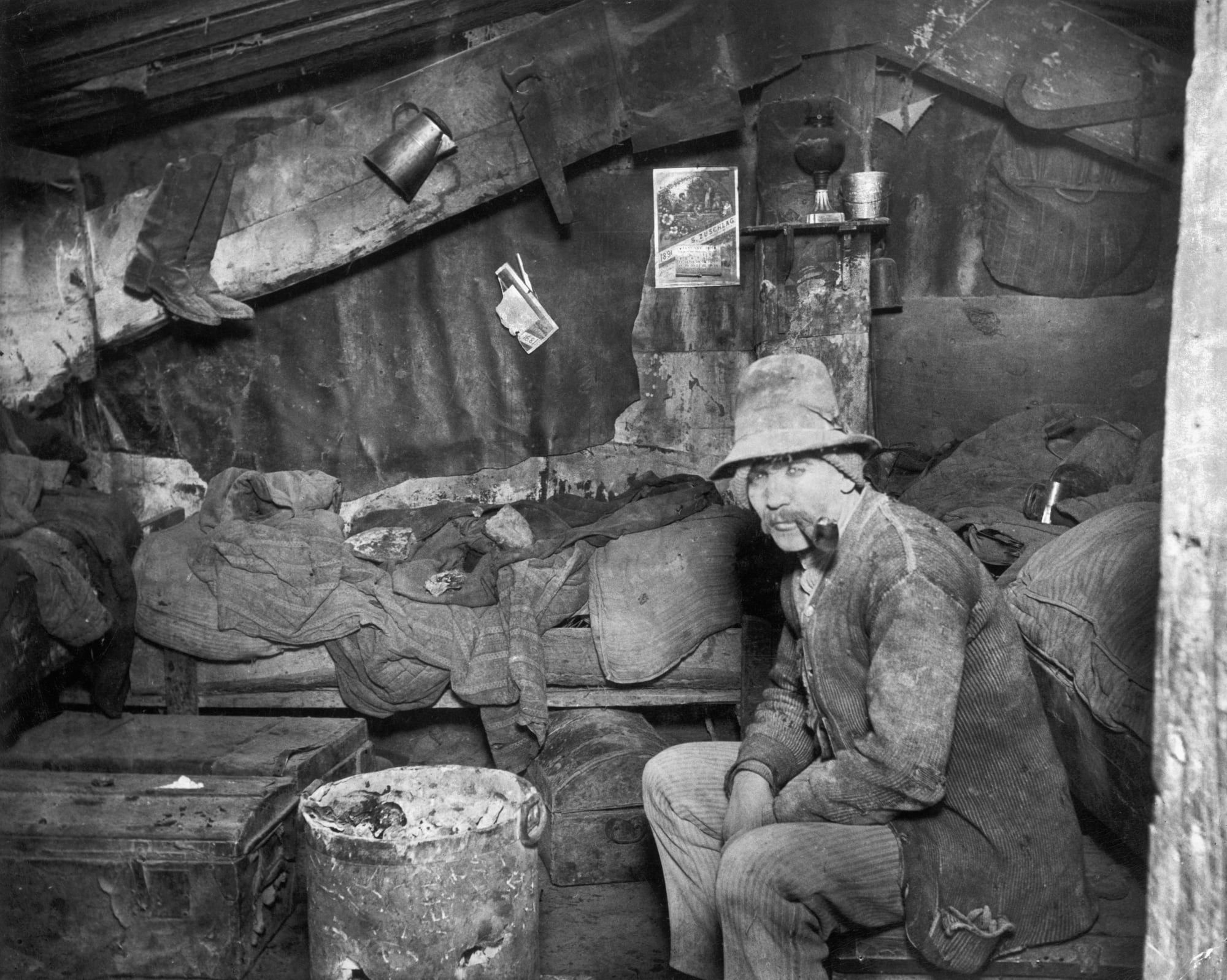

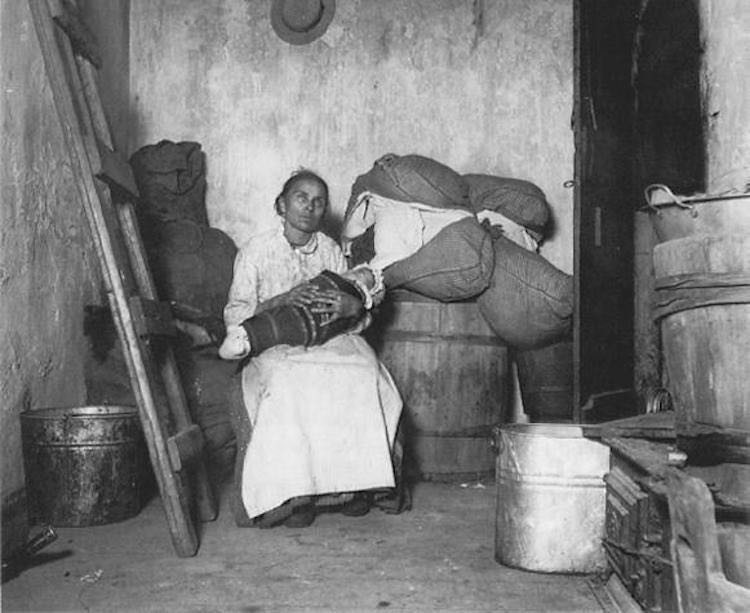

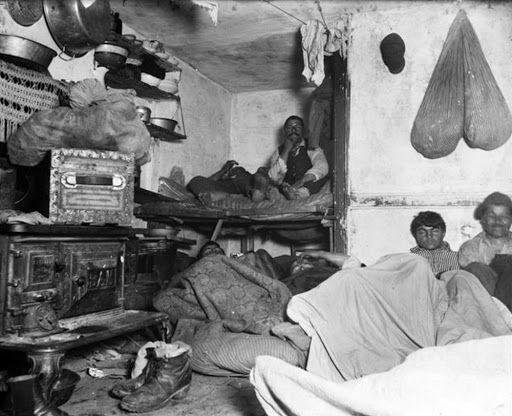

New York crime reporter Jacob Riis used photography to investigate the slums of the city. In these situations, he began experimenting with Blitzlichtpulver (magnesium powder), to obtain brighter images, that suited the poor print quality of newspapers of the time.

Lessons 6 & 7- Photography techniques – The developing process of the negative film

Film developing is done through a sequence of baths in three different solutions of chemicals + water:

1st bath: Developer

Developer is a chemical that reveals the latent image into a visible image by turning pale silver halides crystals in the negative (which are the silver halides that have been hit by light through exposure) into black metallic silver.

More the development = darker negative image = lighter positive print

Concentration of the chemical in the working solution, temperature of the solution, bath duration and agitations during the bath are factors that affect the development process and differ depending on the brands of both the film and the chemical.

That’s why you can find the ideal parameters for the developing of your film in the box fo the film and in the instruction chart of the developer.

Here’s the official Ilford Chart with the parameters needed for the most different Ilford film types in relation to the most commonly used Ilford and non-Ilford developers:

Fomapan 100 Classic data sheet

Bergger developing chart with most common developers:

Hydrofen developer chart:

Other combinations such as Hydrofen with Bergger Pancro 400 can be found with online tools like e.g.:

For Hydrogen with Fomapan:

2ND bath: STOP

The Stop bath is a strong washing bath used to halt the developing process before the Fix bath in order to standardise and fine tune the developing process. It prevents the developing to continue even after we have removed the film out of the developing bath because of residual developer on the film and to avoid to contaminate the fixing solution with developer.

Here’s the Bellini Stop (the tune we use in the lab) chart:

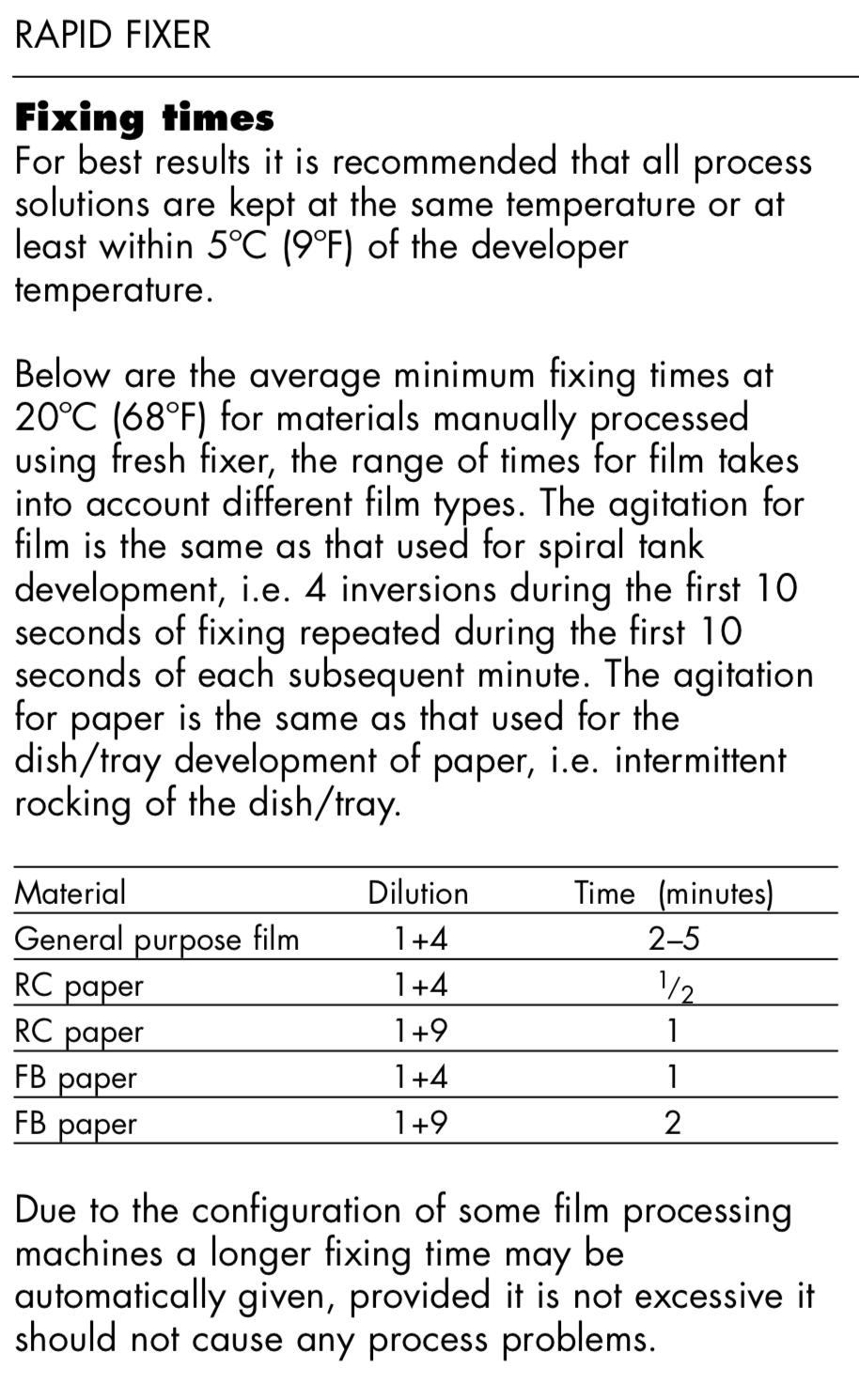

3RD bath: Fix

The FIX bath is used to eliminate all unexposed silver halides (those which were not hit by light during exposure) from the film surface in order to avoid that the film continues to develop (to darken then) after we have finished the developing process. By washing away the residual silver the FIX reveal the plastic transparent part of the negative that will allow the light to pass through during the print process.

Here’s the data sheet and developing chart of the Ilford Rapid Fixer we use in the lab:

Lesson 8, 9 & 10 Photography techniques – Media theatre – Digital photography and lighting

The birth of digital photography – How the sensor works – RGB – notes on color – “Post-photography”

Exercise about photographic reproduction of the work of art. reproduction of painting and sculptures.

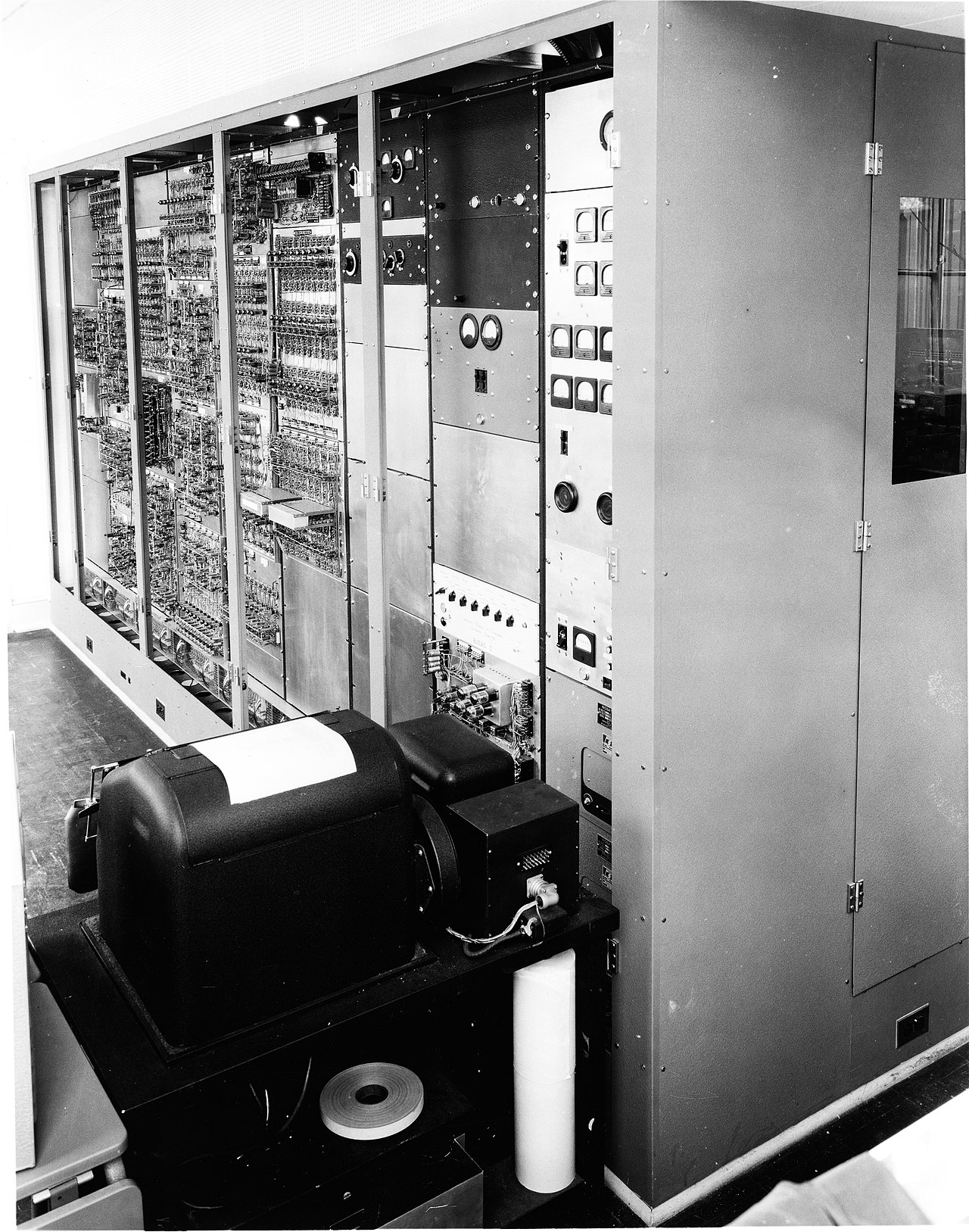

The first digital image was produced through a SEAC (Standards Eastern Automatic Computer) computer by Russell Kirsch at NIST (National Institute of Standards and Technology) in 1957. It was an image of his son Walden.

Initially stored on a 4-track tape recorder, these pictures take four days to transmit back to Earth.

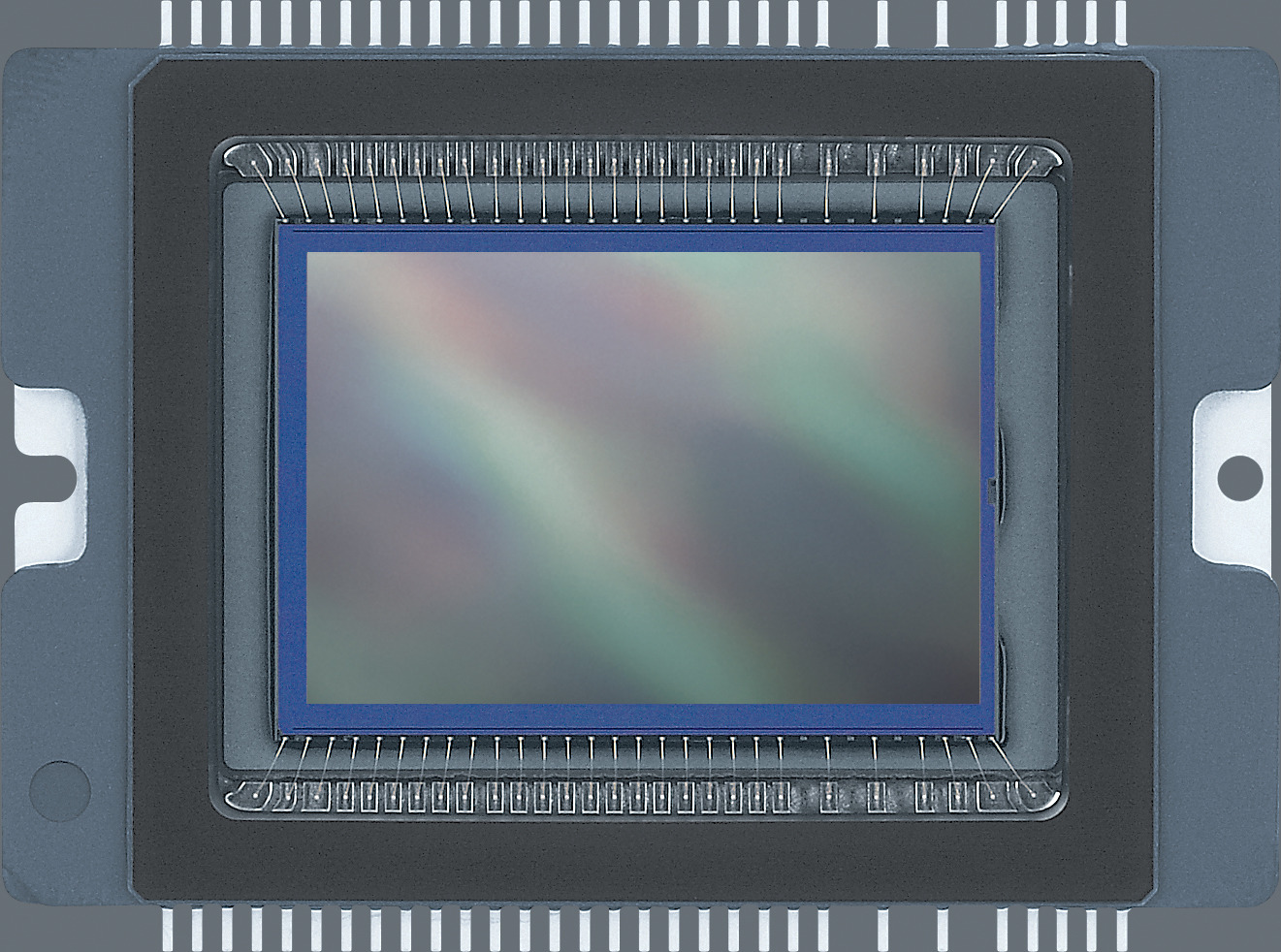

The sensor was invented by Willard S. Boyle and George E. Smith at Bell Labs in 1969 who realized that electric charges could be stored in a semiconductor sensor.

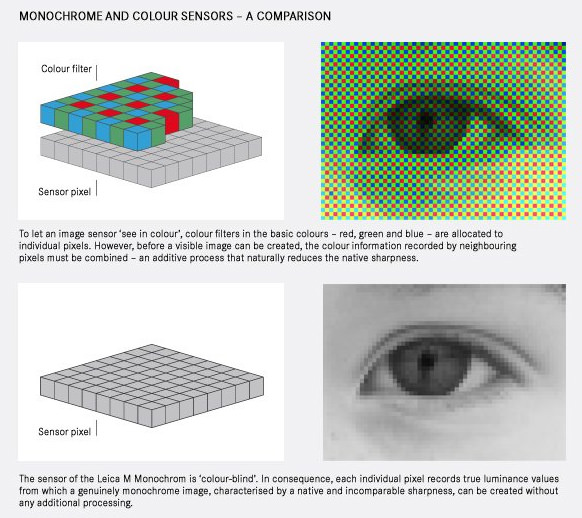

A sensor is made up of millions of cavities called “photosites,” and these photosites open when the shutter opens and close when the exposure is finished (the number of photosites is the same number of pixels your camera has). The photons that hit each photosite are interpreted as an electrical signal that varies in strength based on how many photons were actually captured in the cavity. The range of variations the sensor can interpet (for each photosite/pixel) depends on your camera’s bit depth.

Bit depth is calculated in binary sequences of 0 and 1. An 8 bit image can use a total of eight 0’s and 1’s, where:

00000000 is total black and 11111111 is total white. Al the other combinations are different shades of grades from black to white.

So, a photon (a quantum of electric charge present in light) hits the photosite which measure its intensity in binary system to be elaborated by a CPU and transformed in different shades of gray from black to white.

By placing a RGB (Red, Green, Blue) filter on the photosites the CPU can calculate for each light hitting the sensor how much red, green and blue are in it and elaborate colors.

the first published color digital photograph was produced in 1972 by Michael Francis Tompsett using CCD sensor technology

WHY RGB?

The trichromatic theory of vision was developed by the works of Thomas Young and Hermann von Helmholtz.

In 1802, Young postulated the existence of three types of photoreceptors (now known as cone cells) in the eye, each of which was sensitive to a particular range of visible light.[1]

Hermann von Helmholtz developed the theory further in 1850:[2] that the three types of cone photoreceptors could be classified as short-preferring (violet), middle-preferring (green), and long-preferring (red), according to their response to the wavelengths of light striking the retina. The relative strengths of the signals detected by the three types of cones are interpreted by the brain as a visible color.

In a 1855 paper based on those theories, James Clerk Maxwell proposed that, if three black-and-white photographs of a scene were taken through red, green, and blue filters, and transparent prints of the images were projected onto a screen using three projectors equipped with similar filters, when superimposed on the screen the result would be perceived by the human eye as a complete reproduction of all the colours in the scene.

Produkin-Gorsky archive in Library of Congress

The Autochrome Lumière was an early color photography process patented in 1903[1] by the Lumière brothers.

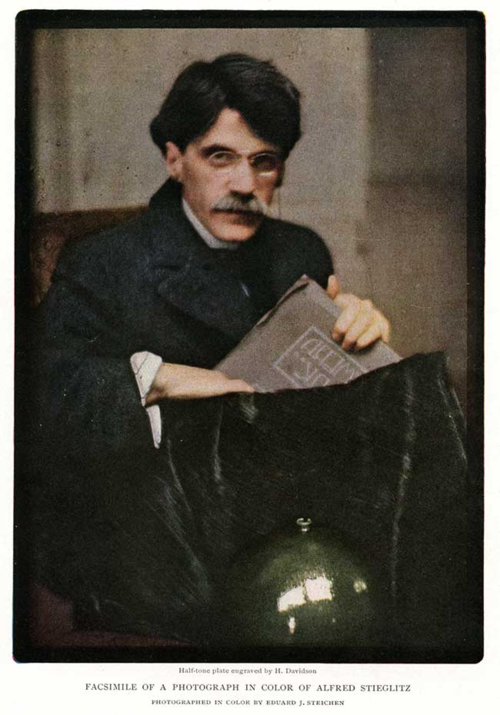

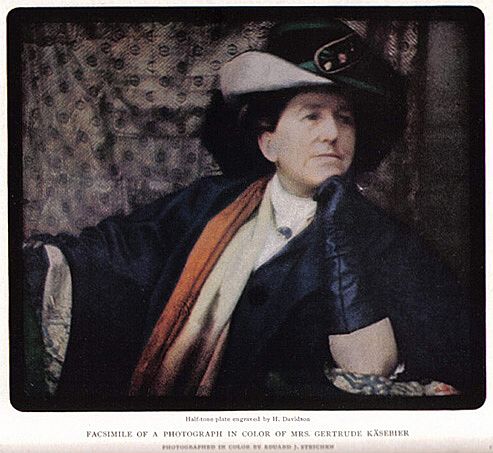

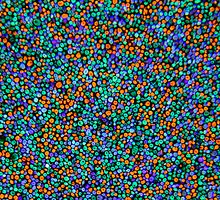

Halftone plate from autochrome, Gertrude Kasbier by Edward Steichen (1907)

The medium consists of a glass plate coated on one side with a random mosaic of microscopic grains of potato starch[7] dyed red-orange, green, and blue-violet (an unusual but functional variant of the standard red, green, and blue additive colors); the grains of starch act as color filters.

Unlike ordinary black-and-white plates, the Autochrome was loaded into the camera with the bare glass side facing the lens so that the light passed through the mosaic filter layer before reaching the emulsion.

The following developments where based on advanced version of this system.

In 1935 Kodak started the production of a film called Kodachrome that used (in principle) a similar technology. The film was composed by different emulsion layers filtered by different colored filter. The top blue layer captured the blue light, letting pass the red and the green one to be captured by other color-filtered emulsion layers. During the developing process each layer would show the color it was sensible to. Kodachrome was a reversal film, meaning that it was directly reversing into a positive image.

In 1941 Kodak produced the Kodacolor film applied the invention to negative film. Not only the light and shadows were inverted but also the colors. The chromogenic process transform each layer into an image with colors that are complementary to the colors of the subject. RGB —> CMY (K).

Kodachrome, Ektachrome and Kodacolor represented the standard of color photography until the diffusion of digital photography.

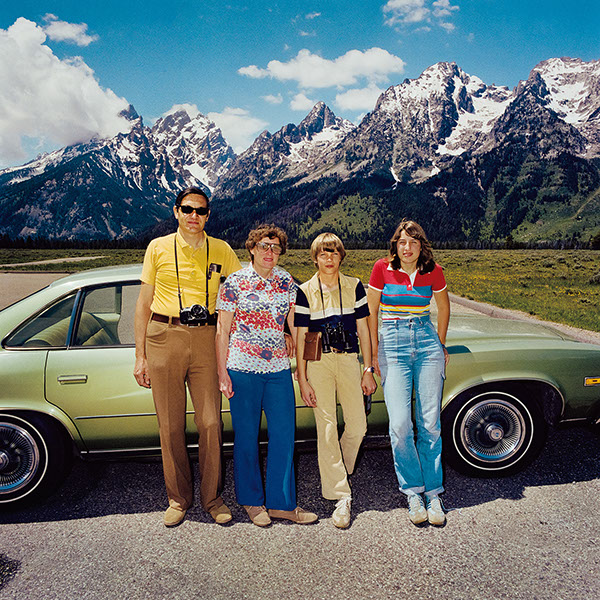

During the 60s and the 70s the number of produced photographs increased drastically and photography definitely became part of the everyday life of the citizen: a common instrument to celebrate and document important family or personal moment (a legacy of the role of photography in the emancipation of the bourgeois?) and a mass activity especially in connection with tourism (a legacy of the relation between photography and XIXth century spirit of Progress?). (see Roger Minick tourists at Yellowstone).

The process of popularization had started quite a while earlier:

George Eastman (1854–1932), a former bank clerk from Rochester, New York invented and marketed the Kodak #1 in 1888, “a simple box camera that came loaded with a 100-exposure roll of film.

When the roll was finished, the entire machine was sent back to the factory in Rochester, where it was reloaded and returned to the customer while the first roll was being processed. […]

To underscore the ease of the Kodak system, Eastman launched an advertising campaign featuring women and children operating the camera, and coined the memorable slogan: “You press the button, we do the rest.”

Within a few years of the Kodak’s introduction, snapshot photography became a national craze. Various forms of the word “Kodak” entered common American speech (kodaking, kodakers, kodakery), and amateur “camera fiends” formed clubs and published magazines to share their enthusiasm. By 1898, just ten years after the first Kodak was introduced, one photography journal estimated that over 1.5 million roll-film cameras had reached the hands of amateur shutterbugs.” (Mia Fineman on Met Museum website)”

Back to digital photography, those numbers are no longer extraordinary if we compare them with what we are experiencing after the invention of digital photography and, even more, after the introduction of smartphones and social media.

“Flash back to the glory days of film photography: 2000. That year, Kodak announced that consumers around the world had taken 80 billion photos, setting a new all-time record. The explosion of digital photography has since rendered such statistics almost quaint. This year, according to the market research firm InfoTrends, global consumers will take more than one trillion digital photos.

The growth in the number of photos taken each year is exponential: It has nearly tripled since 2010 and is projected to grow to 1.3 trillion by 2017. The rapid proliferation of smart phones is mostly to blame. Seventy-five percent of all photos are now taken with some kind of phone, up from 40 percent in 2010. Full-fledged digital cameras now represent only 20 percent of the tally, and are expected to drop to just 13 percent by 2017, InfoTrends said.” (The New York Times, July 29, 2015)

Media experts estimated that in 2015 only world population produced more photographs than those taken on film in the entire history of photography.

Post-photography

Exercise: Open a jpg file with a txt editor. Change something and save. change extension to jpg again. see what happen

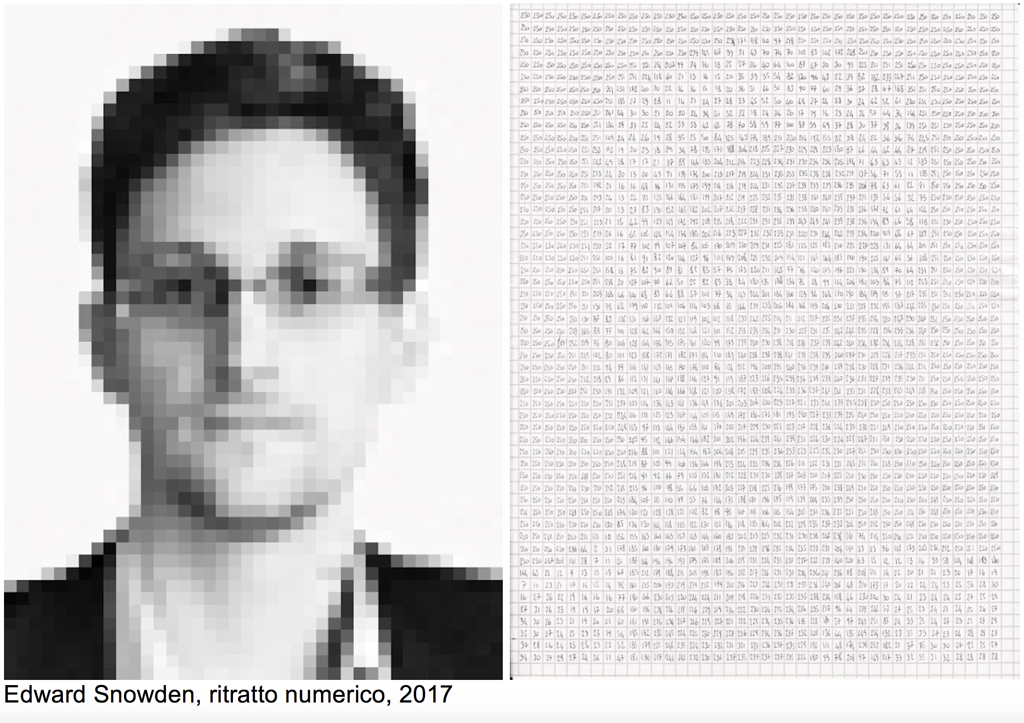

Fabrizio Bellomo “Ritratti numerici” (2017)

grid, pixels, binary, digital

Thomas Ruff “Nudes” (2000)

Found images, digital corruption, spectacularization, medium

The source images in Ruff’s “nudes” (a classical topic in art history) series were culled from the sea of pornography that floods the Internet. The artist, who often works with appropriated imagery, downloaded the pictures and manipulated them on his computer, intensifying colors, blurring outlines, and greatly enlarging the scale. At once visually ravishing and provocatively blunt, the photographs address the collapse between public and private in contemporary culture as well as the tradition of voyeuristic delectation inspired by the many pictures of female flesh hanging in this or any other art museum.

By enlarging the images Ruff plays with people attraction to look (like in porn on the internet) at something private but immediately disappoints them when they discover those images are blurred. In a gallery you can see very large nudes hanging on the walls and they would appear sharpen. But once you get close you will no longer see the details you were seeking.

https://www.davidzwirner.com/exhibitions/2000/nudes

Thomas Ruff, “jpegs”. (2004)

pixels, quality of information in digital communication, medium

Erik Kessels “In almost every picture”, book series, 2002 – ongoing

Found photos, overproduction of images, self publishing, social effects of diffusion of photography, medium

https://www.erikkessels.com/in-almost-every-picture

Erik Kessels, “My feet” (2014)

Overproduction, spectacularization of private, self-alimented iconography, repetition

Erik Kessels, “24hrs in photos”

Overproduction, spectacularization of private

Exhibition at Foam, Amsterdam.

Exhibition at Foam, Amsterdam.

We’re exposed to an overload of images nowadays. This glut is in large part of the result of image-sharing sites like Flickr, networking sites like Facebook and Instagram and picture-based search engines. Their contact mingles the public and private, with the very personal being openly displayed. By printing 350.000 images, uploaded in a twenty-four hours period, the feeling of drowning in representations of other peoples’ experiences is visualized.

https://www.erikkessels.com/24hrs-in-photos

Dina Kelberman, “I’m Google” (2011)

Overproduction, algorythm, code

https://dinakelberman.tumblr.com/

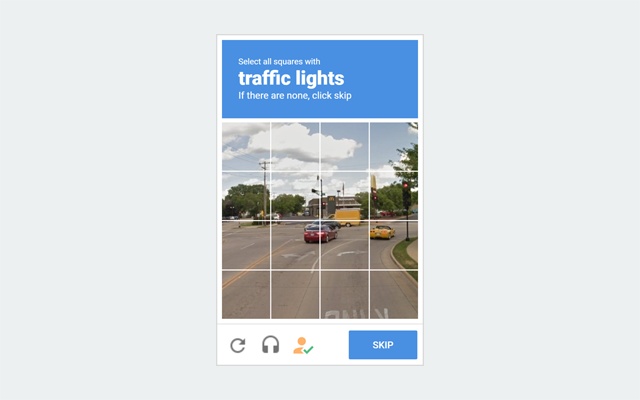

Google image algorythm. Captcha

Taryn Simon, Image Atlas

Image search, algroythm, code

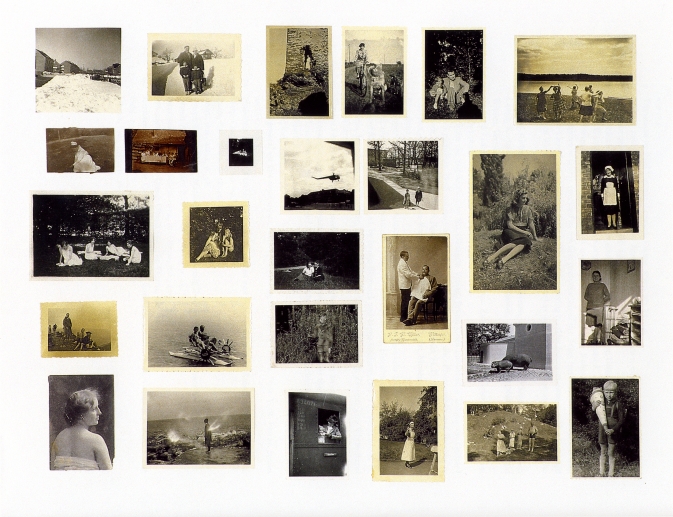

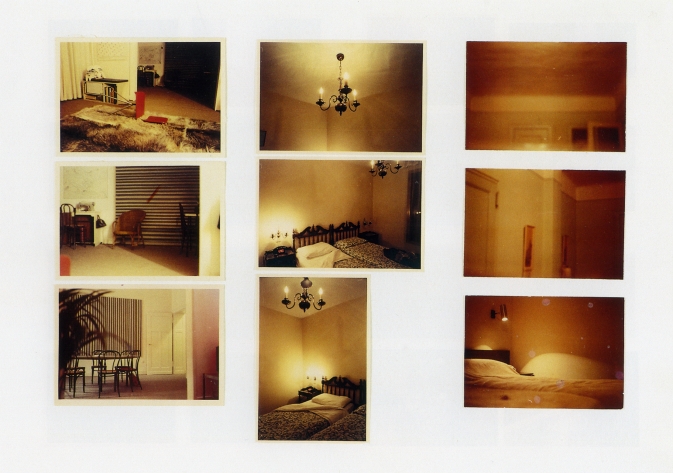

Gerhard Richter, Atlas (1960s-2015?)

Overproduction, iconography, photographs for painters

A collection of photographs, newspaper cuttings and sketches that the artist has been assembling since the mid 1960s. A few years later, Richter started to arrange the materials on loose sheets of paper.

“In the beginning I tried to accommodate everything there that was somewhere between art and garbage and that somehow seemed important to me and a pity to throw away.”

https://www.gerhard-richter.com/it/art/atlas?sp=all

Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin, Divine Violence (2013)

Archive, re-interpretation,

Illustrating a Holy Bible with pictures from The Archive of Modern Conflict (London)

Giorgio di Noto, The Arab revolt (2011)

Media, first-hand information, appropriation

From the website of the author:

“The documentation for these events was for the most part provided by the populations involved who, using smart-phones and small video cameras, published and shared pictures and videos of the revolts on the internet.

[…]

The black-and-white instant films made it possible to capture and extract single images from the fast-flowing stream of the videos without showing the screen surface: both pixels and low-definition flaws disappeared, melting with the film’s peculiar emulsion and bringing the virtual image back to its concrete state as a real and material object.

Through this ambiguity, which managed to conceal the nature of the photographs, I wanted to represent the overlap between documenting and witnessing, between pictures produced (and post-produced) by photographers and home-made pictures provided by people actually participating in the events.”

https://www.giorgiodinoto.com/thearabrevolt#0

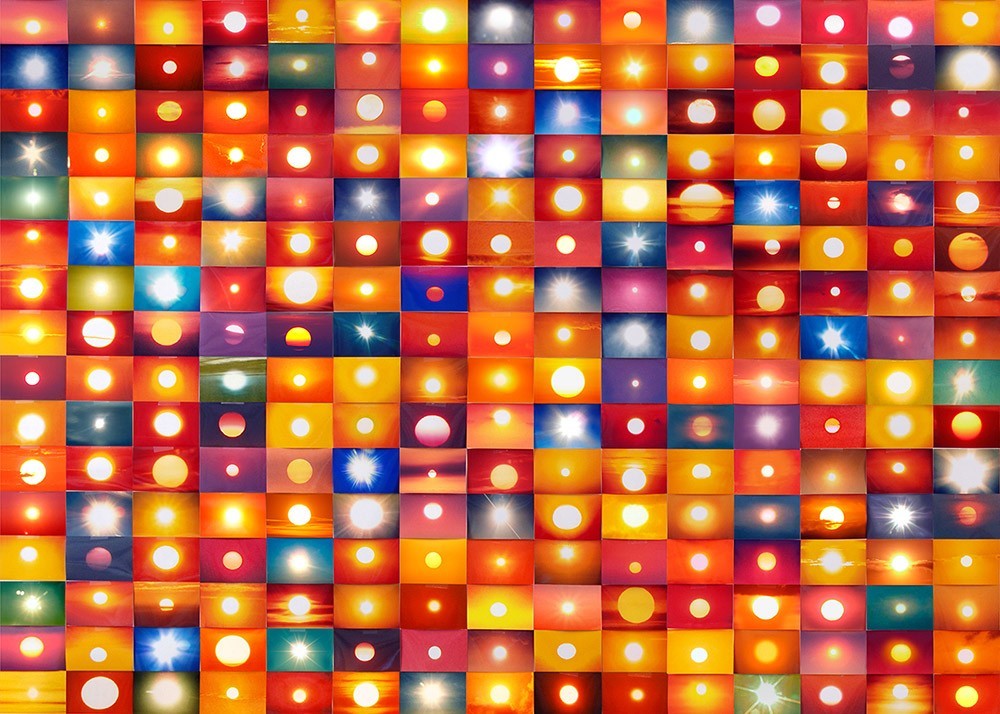

Penelope Umbrico, “Suns from Sunsets from Flickr”, 2006 – ongoing

Overproduction, self-omologation, iconography

http://www.penelopeumbrico.net/index.php/project/suns-from-sunsets-from-flickr/

Mishka Hener, Dutch landscapes, 2011

google earth, landscape, control

Dutch military zones censored on Google Earth

https://mishkahenner.com/dutch-landscapes

Jeff Guess, Fonce Alphonse, 1993

Surveillance, cameras everywhere

Fonce Alphonse represents one of the most intimate and yet coded events in the life of a couple, marriage. For the occasion, my fiancée and I intentionally exceeded the speed limit on our wedding day, put the pedal to the metal in order to have the Police Nationale snap our nuptial portrait.

https://www.guess.fr/works/fonce_alphonse

Aram Bartholl, 15 seconds of fame, (2009)

Surveillance, cameras everywhere

https://arambartholl.com/15-seconds-of-fame/

Michael Wolf, “A series of unfortunate events” (2011)

Google street view, screen, appropriation

https://photomichaelwolf.com/#asoue/29

Manu Luksch, Faceless, 2007

Surveillance, cameras everywhere

Josh Poehlein, Modern History (2007)

appropriation , collage, information reliability

https://www.inthein-between.com/the-modern-histories-of-josh-poehlein/

Lesson 11 (DAD) History of Photography – Art or not? Documental photography – Public campaigns

Art or not?

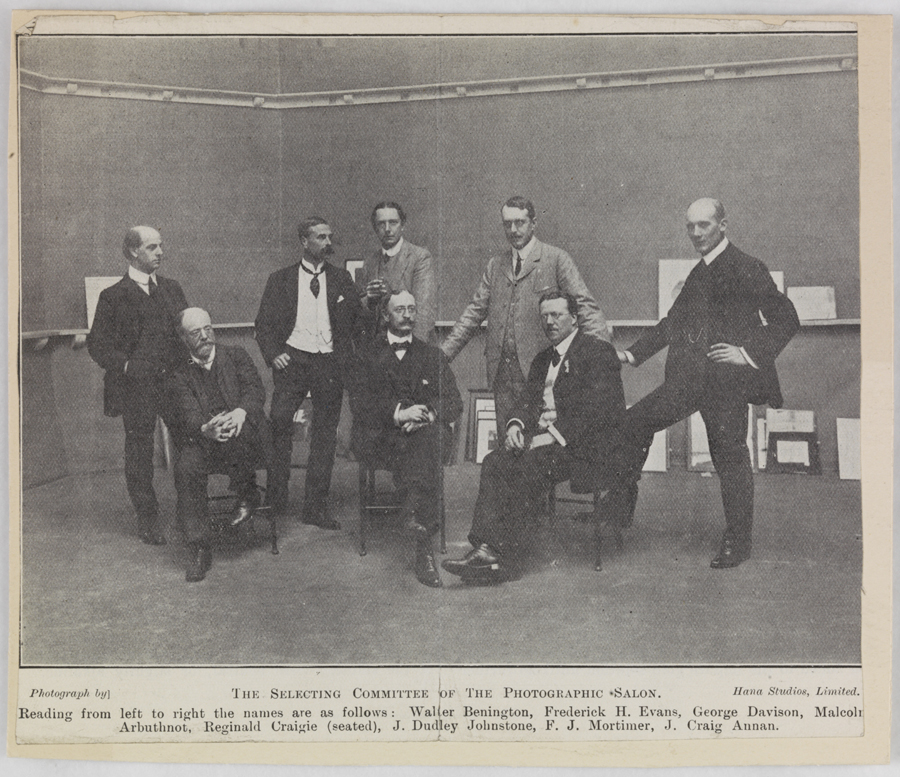

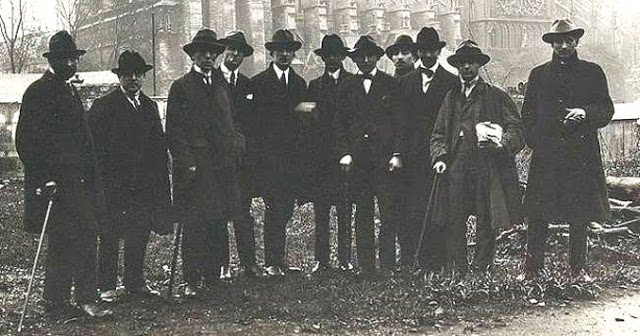

The first “concrete action” in favor of an artistic photography was taken by the Linked Ring, a group of photographers who seceded from the Photographic Society, disappointed by the latter’s rejection of artistic photography.

The Ring organized in London a series of exhibitions entitled Photographic Salon to host the works of pictorial photographers.

In their manifesto the Linked Ring called for:

– The emancipation of photography, rightly called pictorial, from the restraining and mortifying bondage of what was strictly scientific or technical, with which its identity had been confused for too long.

– its development as an independent art

– Its progress on the road they thought was right to reach, given the logical possibilities open to their mental vision, the promised land.

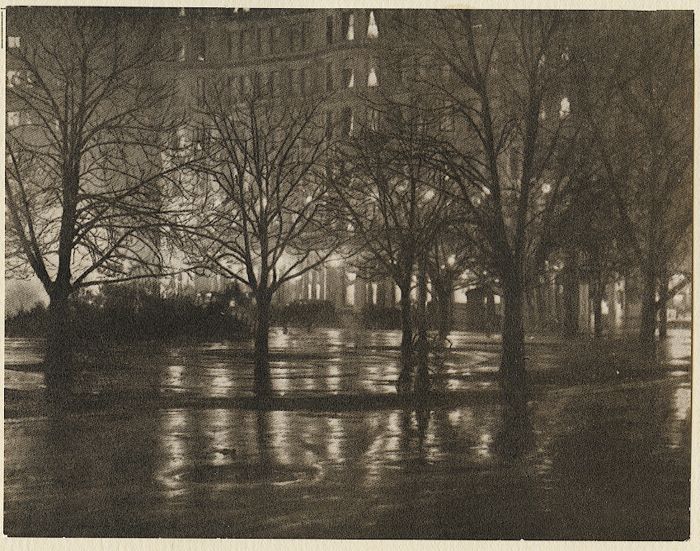

Stieglitz returned to New York and became director of the Society of Amateur Photographers which then merged into the New York Camera Club and transformed its quarterly magazine Camera Notes which began to host and promote exhibitions of pictorial photography.

Stieglitz was a charismatic leader and the Club soon became the place to be for many pictorialist photographers.

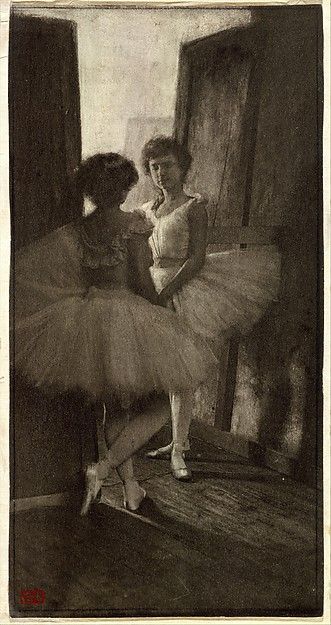

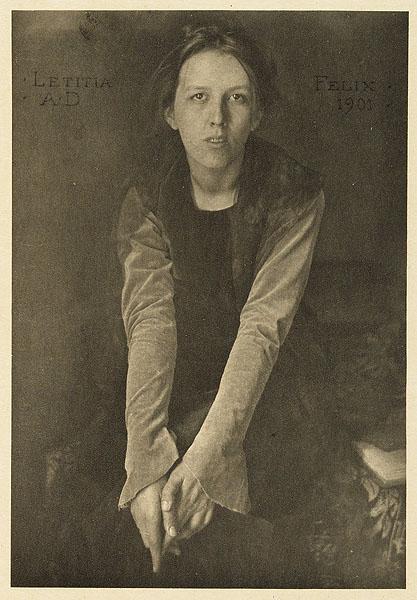

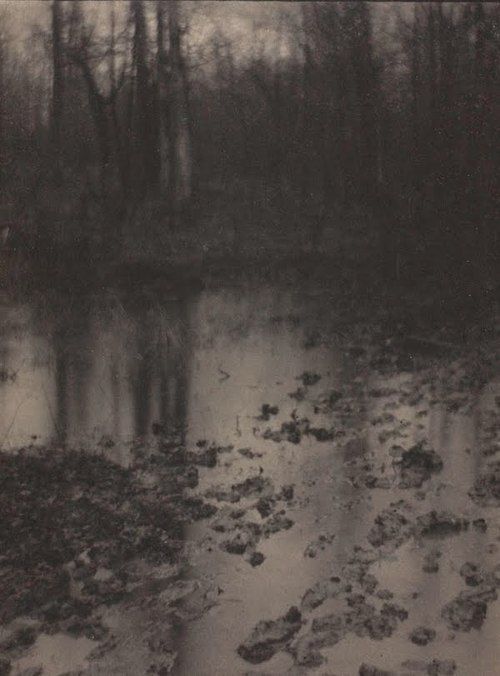

Steichen solitude 1901

Steichen solitude 1901

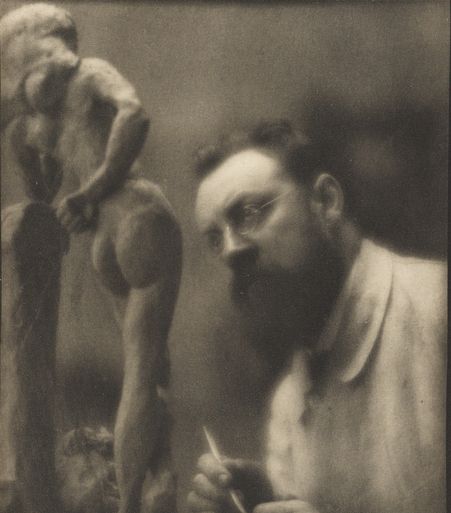

steichen matisse, “la serpentine” 1909

Eduard Steichen is the first of the photographers admitted to the Salon des Beaux Arts in Paris and Stieglitz announced it pompously on Camera Notes, as a personal victory.

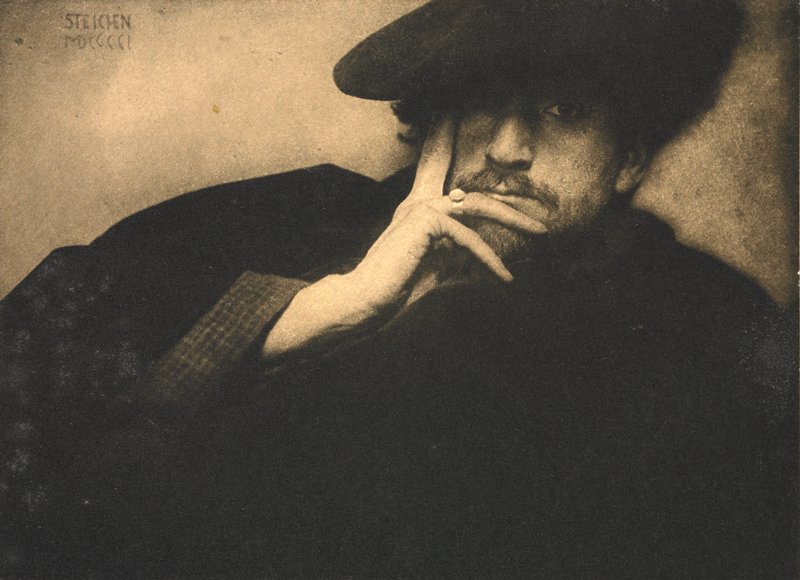

In 1902 Stieglitz founded a new society called the Photo-Secession (from the German and Austrian Art Nouveau Secession) whose partners included Kasebier, Steichen, Clarence White, and others.

Photo-Secession aimed to:

– Promoting the progress of photography as a pictorial expression

– Promoting meetings and associations among Americans who practice art or are interested in it

– Organizing from time to time, in different places, exhibitions not necessarily limited to the Photo-Secession or to American artists.

Stieglitz was fired as director of Camera Notes, as the other partners thought he would use it as a media outlet for the photo secession, and Stieglitz founded a new quarterly magazine under the name Camera Work that published 50 issues between 1903 and 1917. Steichen was the art director.

The first issue was dedicated to Kasebier, the second to Steichen…

Reaction:

Avant-garde painters saw a liberation in photography. It was no longer their role to represent reality, or perhaps there was no longer any need to pretend to do so. Cubism and abstract art were born.

Photographers and photography critics began to defend the uniqueness of photography as a medium.Photography should not be considered art because it imitates paintings but can be art as a means of viewing the real.

In a review of a Photo Secession exhibition at the Carnagie Institute in 1904, the critic Sadakichi Hartmann wrote:

“And what do I call straight photography,” they may ask, “Can you define it?” Well, that’s easy enough. Rely on your camera, on your eye, on your good taste and your knowledge of composition, consider every fluctuation of color, light, and shade, study lines and values and space division, patiently wait until the scene or object of your pictured vision reveals itself in its supremest moment of beauty. In short, compose the picture which you intend to take so well that the negative will be absolutely perfect and in need of no or but slight manipulation. I do not object to retouching, dodging, or accentuation, as long as they do not interfere with the natural qualities of photographic technique. Brush marks and lines, on the other hand, are not natural to photography, and I object and always will object to the use of the brush, to finger daubs, to scrawling, scratching, and scribbling on the plate, and to the gum and glycerine process, if they are used for nothing else but producing blurred effects.

Do not mistake my words. I do not want the photographic worker to cling to prescribed methods and academic standards. I do not want him to be less artistic than he is to-day, on the contrary I want him to be more artistic, but only in legitimate ways.

[…]

To me the Photo-Secession movement is merely the extreme swing of the pendulum which is necessary ere a reaction in photographic work will bring it back to a normal, but at the same time much higher, artistic plane than it has ever occupied before.

I myself have been concerned with this movement from the very start; I have stood by it through thick and thin because I realized that my ideal of straight photography could only be reached by making concessions and by roundabout ways. But now as the time for a reaction has come, I sincerely hope that my words will have so much weight with some of the workers that they will read this plea for straight photography and give it serious consideration; for it is my innermost conviction that there must come a change if we do not want to sacrifice all we have gained. I want pictorial photography to be recognized as a fine art. It is an ideal that I cherish as much as any of them, and I have fought for it for years, but I am equally convinced that it can only be accomplished by straight photography.”

Stieglitz, clever as usual, organized many exhibitions of avant-garde painting in America exhibiting Cezanne, Brancusi, Matisse, Picasso, Braque, Picabia…

https://archive.artic.edu/stieglitz/portraits-of-georgia-okeeffe/

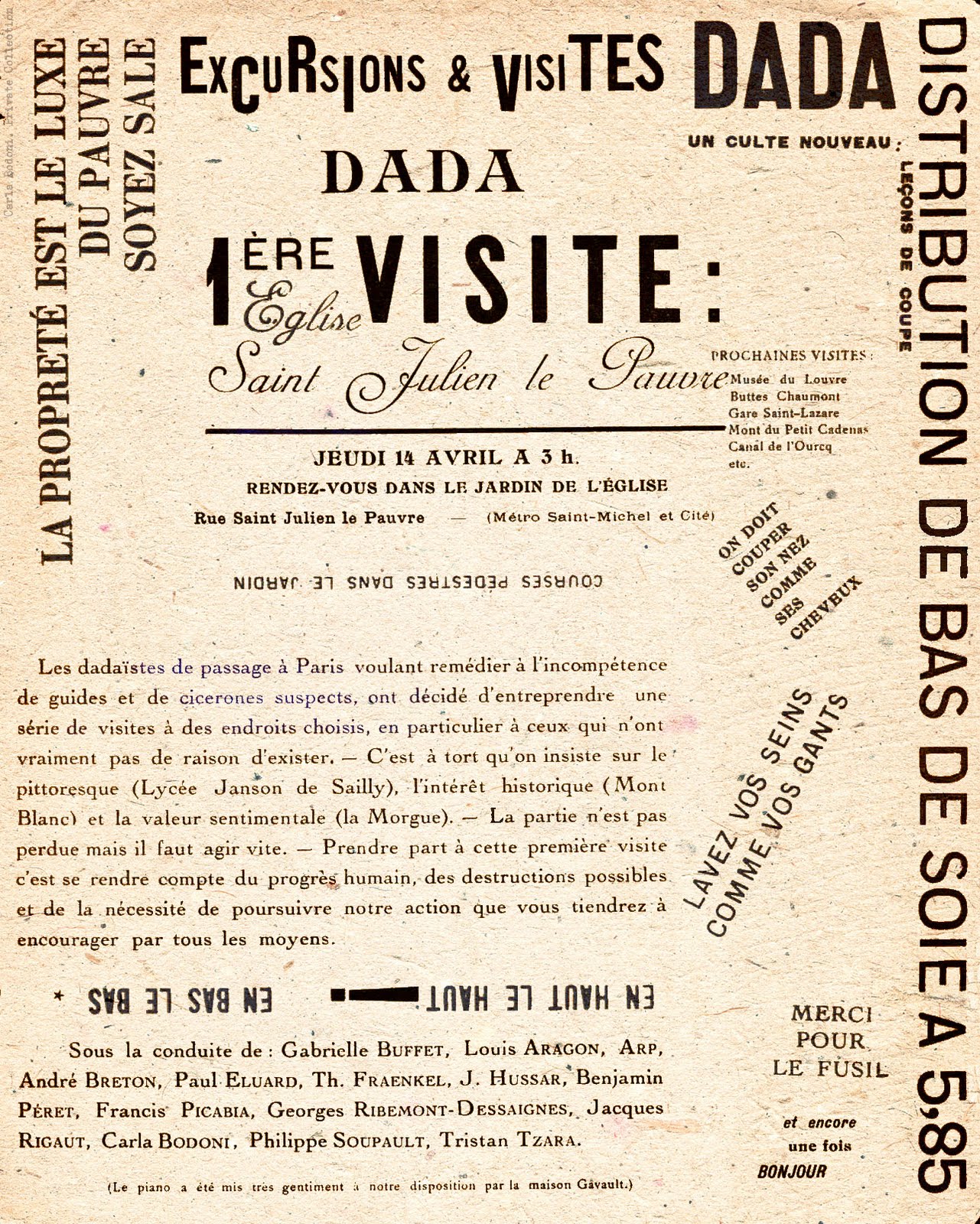

Dada Zurich Christian Schad.

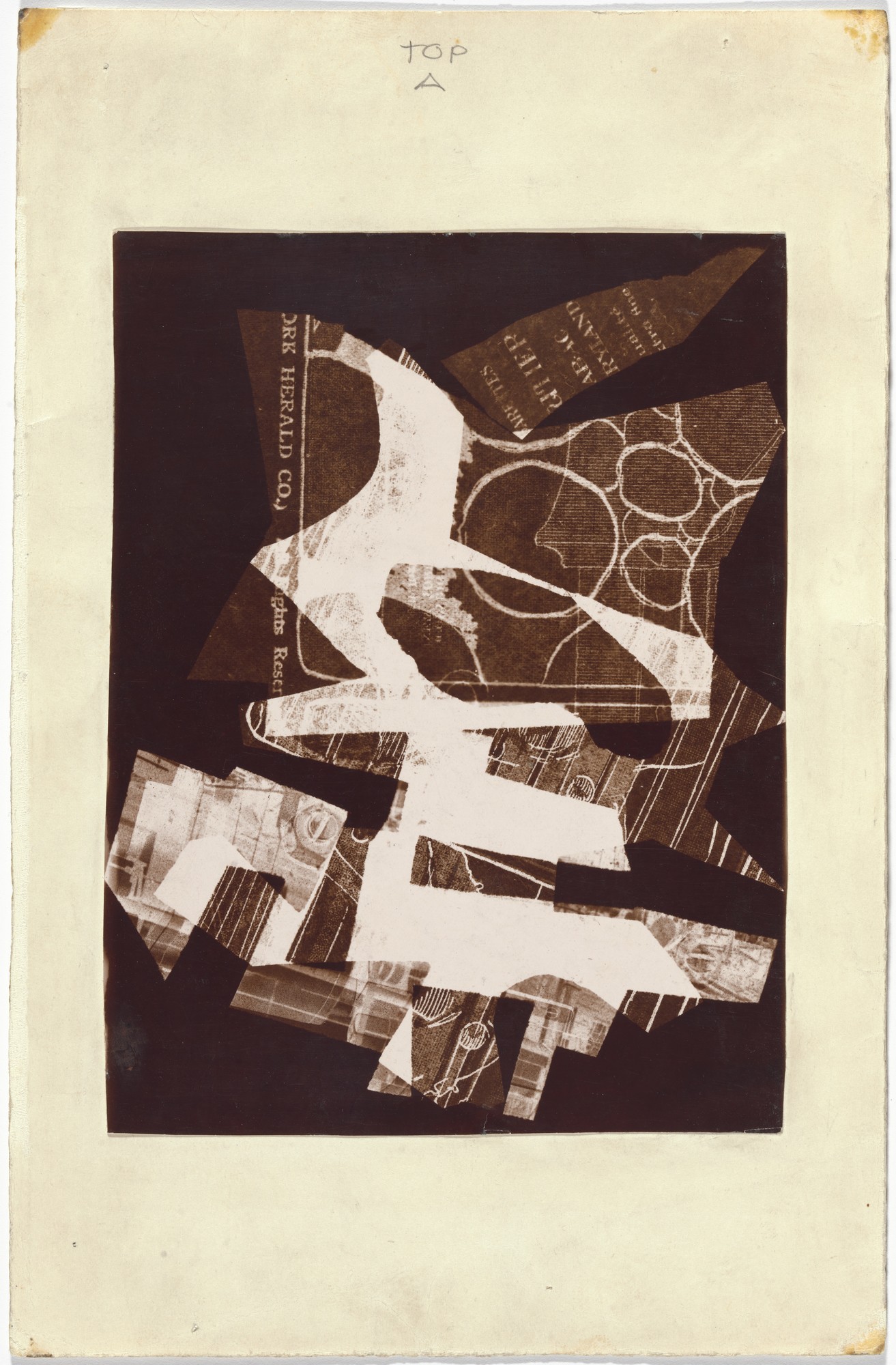

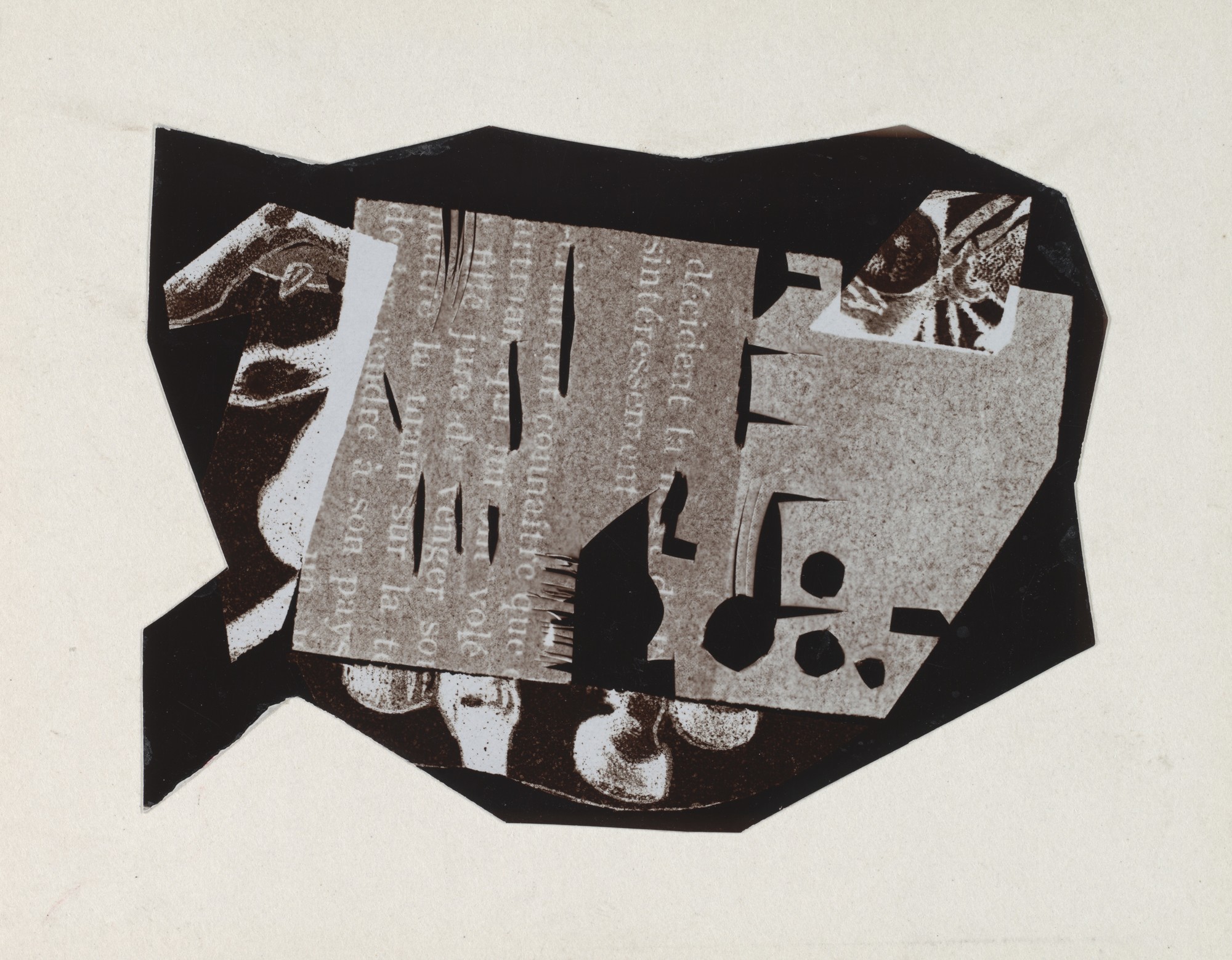

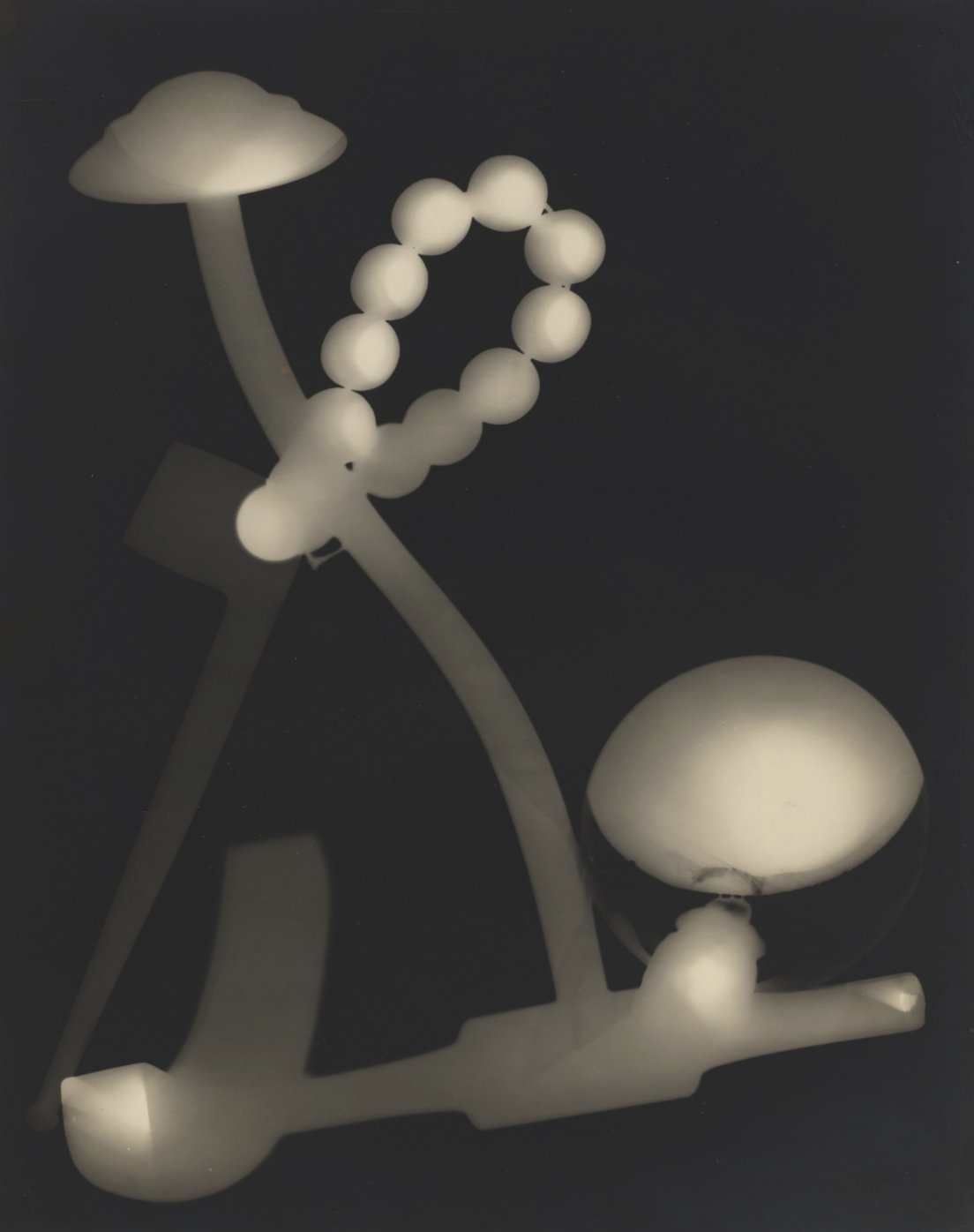

Man ray rayographs

Laszlo Moholy-Nagy

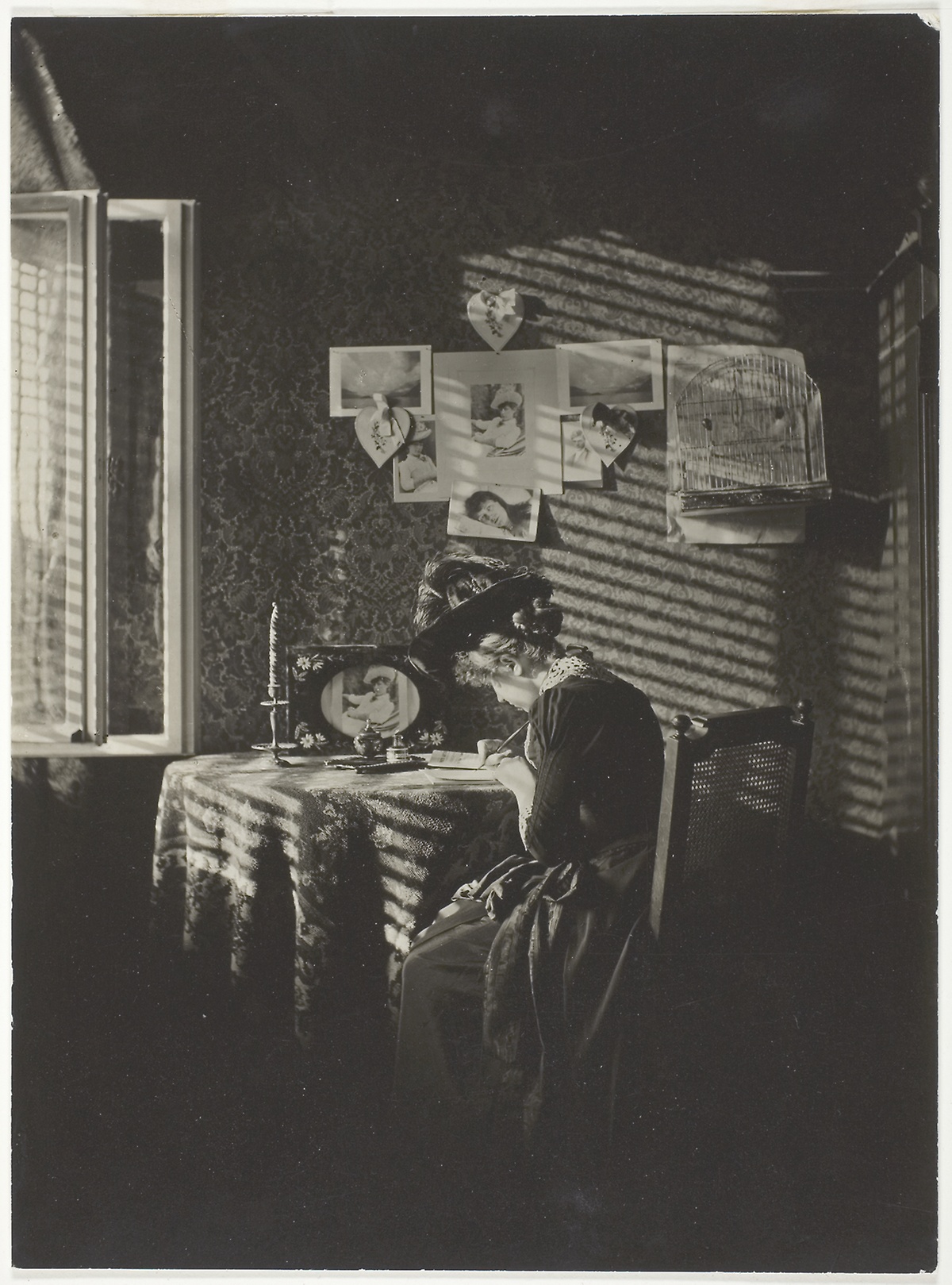

Social photography, documentary photography, public photographic surveys

Parallel to Straight Photography runs a focus on social photography as a means to document the state of a territory, a country, a population.

In 1927 Jean-Eugene-August Atget died unknown (only the magazine “La Revolution Surrealiste” had published his views).

He had worked on the urban landscape of Paris in a classical way (as far as techniques are concerned) but with a personal and visionary approach setting many future trends in visual storytelling of social landscape.

Thanks to Straight Photography and to visual storytellers such as Atget, photographic language was fully recognized as a historical document at those time.

As early as 1889 the British Journal of Photography wrote about the need to propduce (trough photography a record as complete as it can be made … of the present state of the world and to provide ‘valuable documents’ for the future.

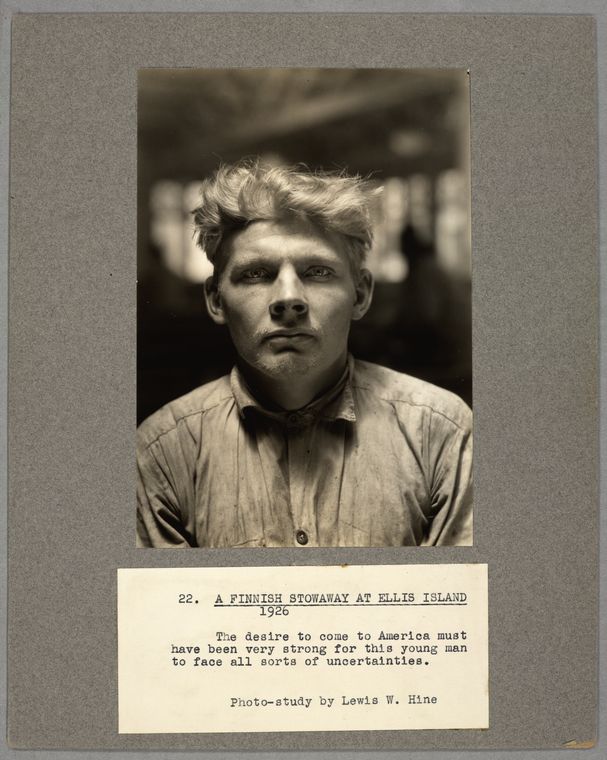

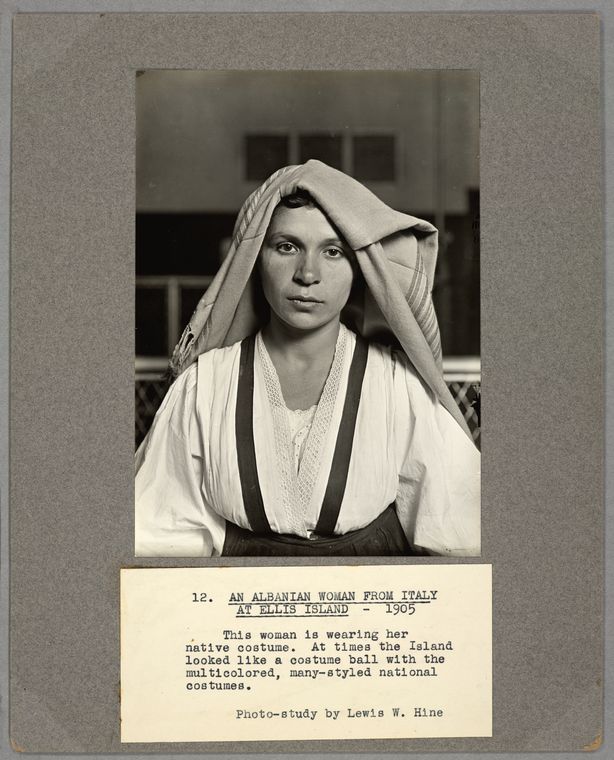

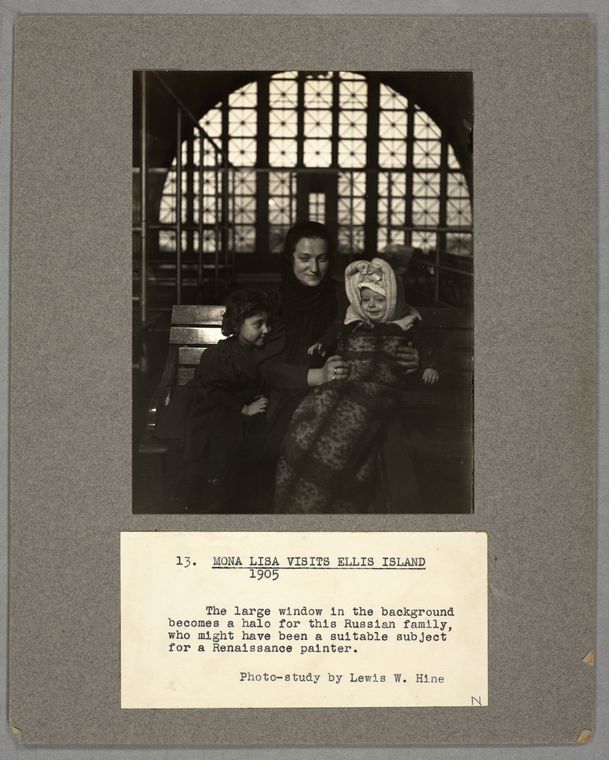

Lewis Hine in the archive of the National Child Labor Committee

Founded in 1904, the National Child Labor Committee set out on a mission of “promoting the rights, awareness, dignity, well-being and education of children and youth as they relate to work and working.” Starting in 1908, the Committee hired Lewis W. Hine (1874-1940), first on a temporary and then on a permanent basis, to carry out investigative and photographic work for the organization. The more than 5,100 photographic prints and 355 glass negatives in the Prints and Photographs Division’s holdings, together with the often extensive captions that describe the photo subjects, reflect the results of this early documentary effort, offering a detailed depiction of working and living conditions of many children–and adults–in the United States between 1908 and 1924.

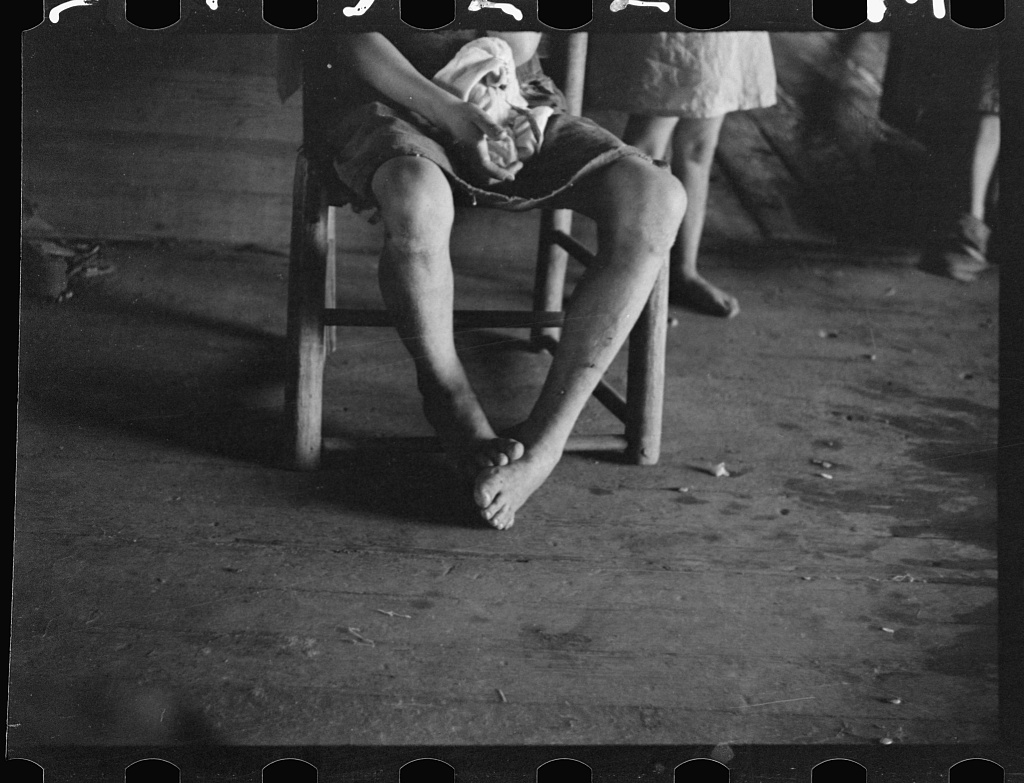

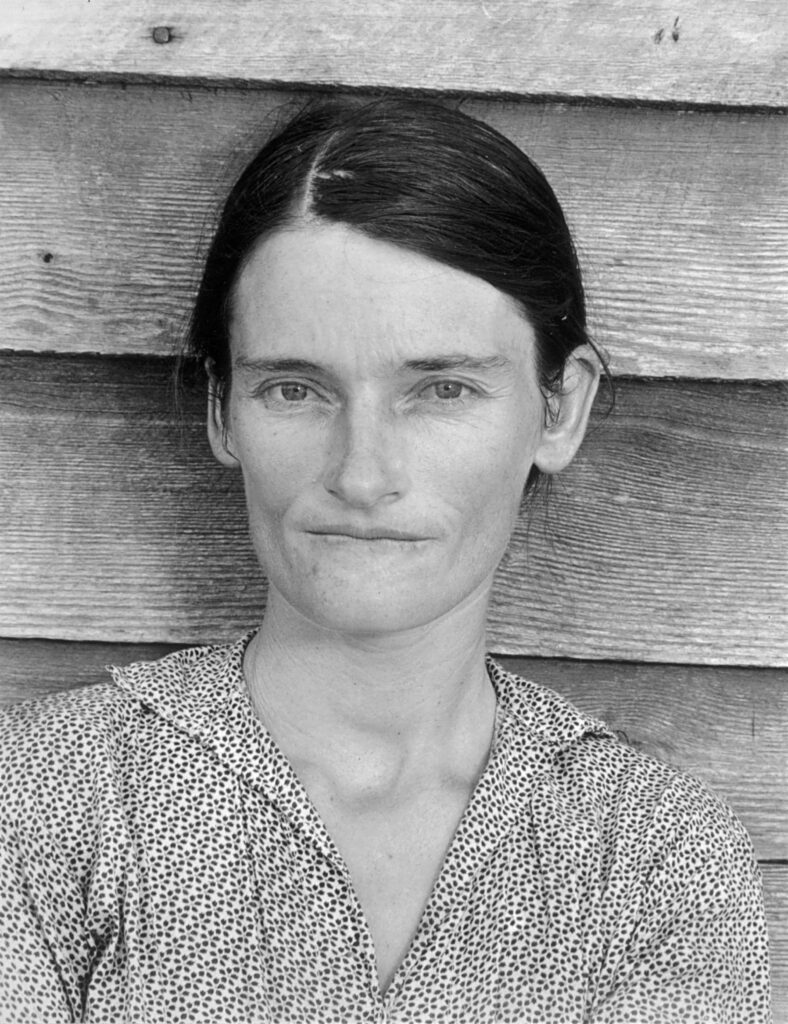

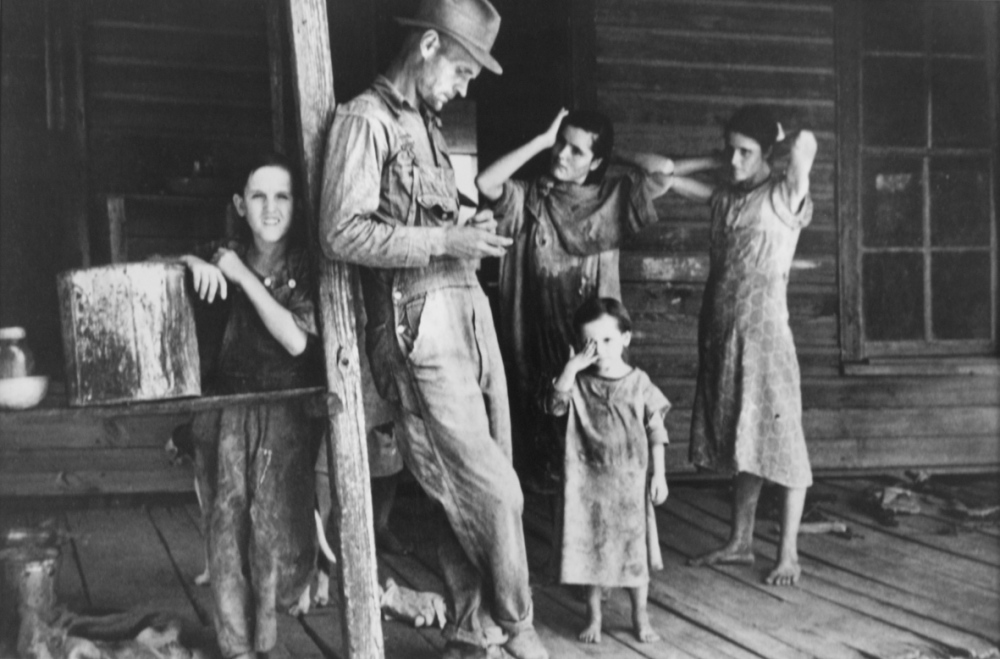

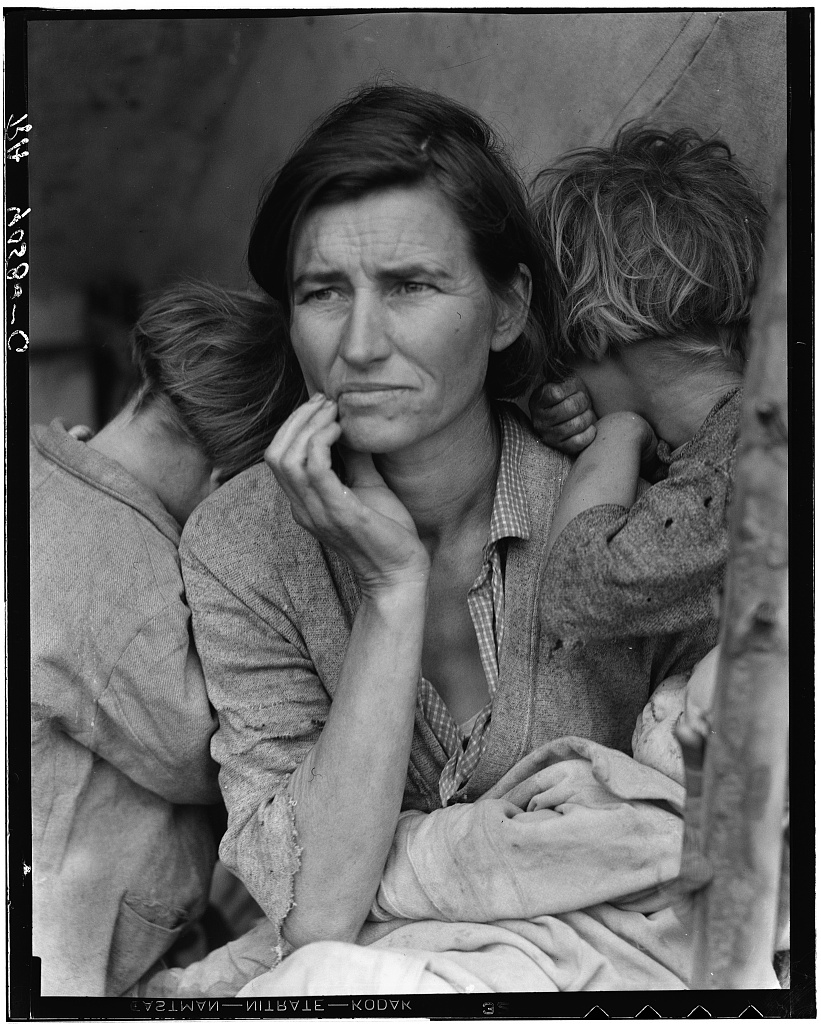

FSA – Farm Security Administration – 1937-1944

In 1937 in the framework of the New Deal (the reform program initiated by Franklin D Roosevelt), the Farm Security Administration commissioned a group of photographers to document the state of the American mainland and thus allow administrators to see the situations on which to intervene or invest.

One of the first to be hired was Walker Evans.

Dorothea Lange

https://www.loc.gov/collections/fsa-owi-color-photographs/about-this-collection/

https://www.loc.gov/collections/fsa-owi-black-and-white-negatives/about-this-collection/

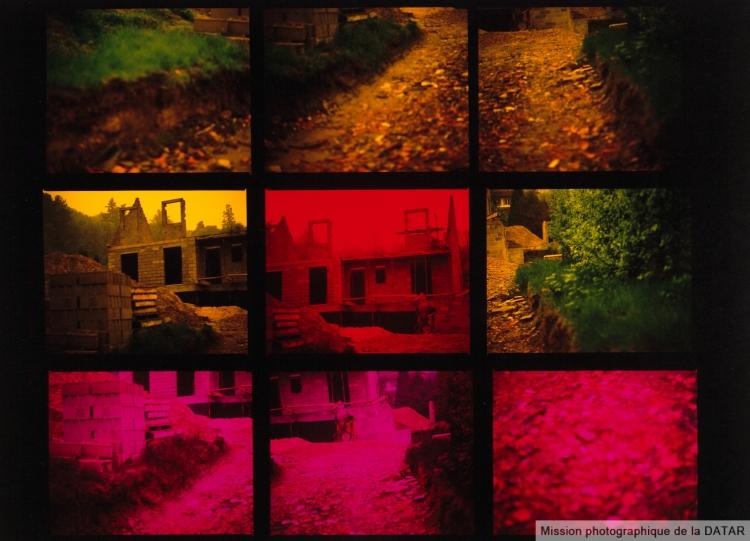

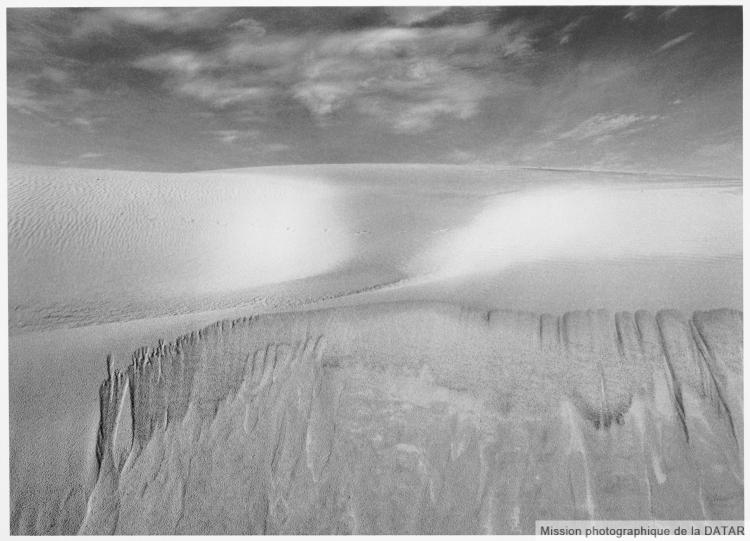

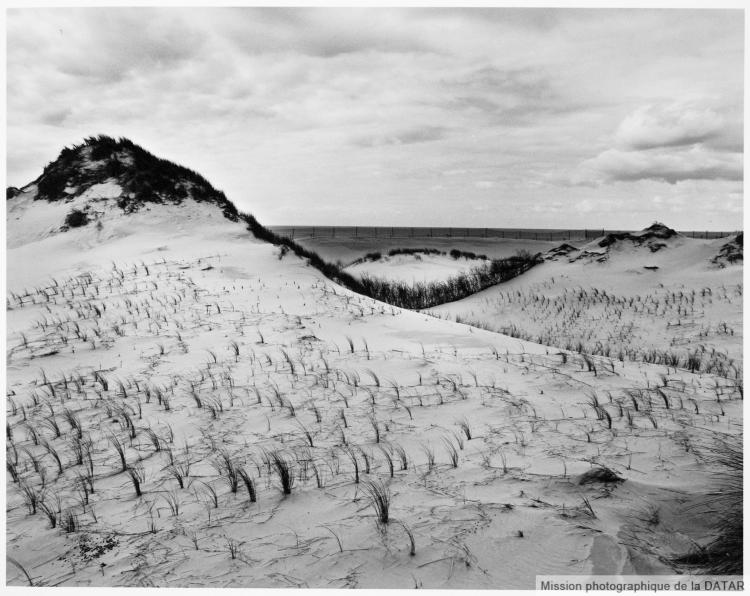

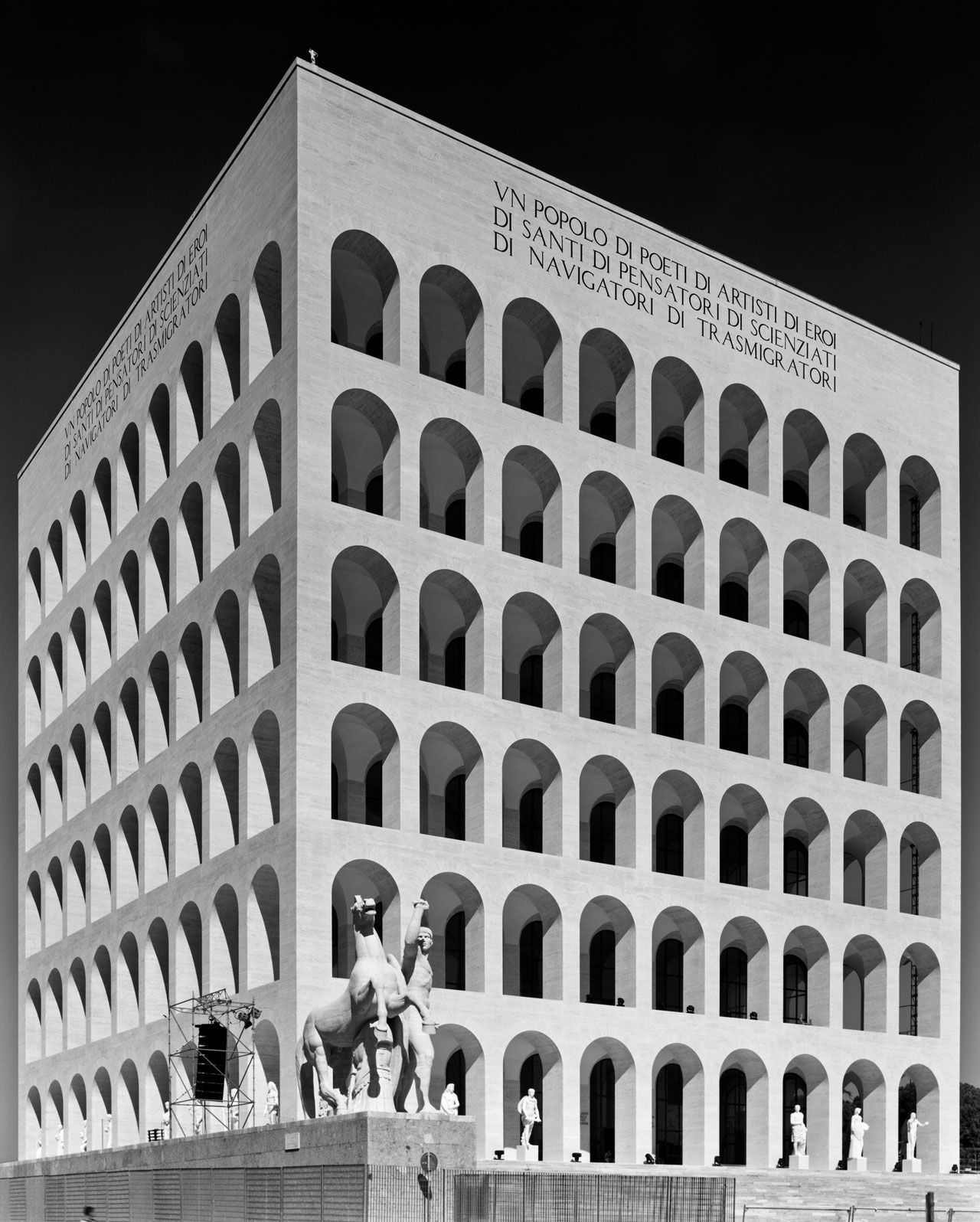

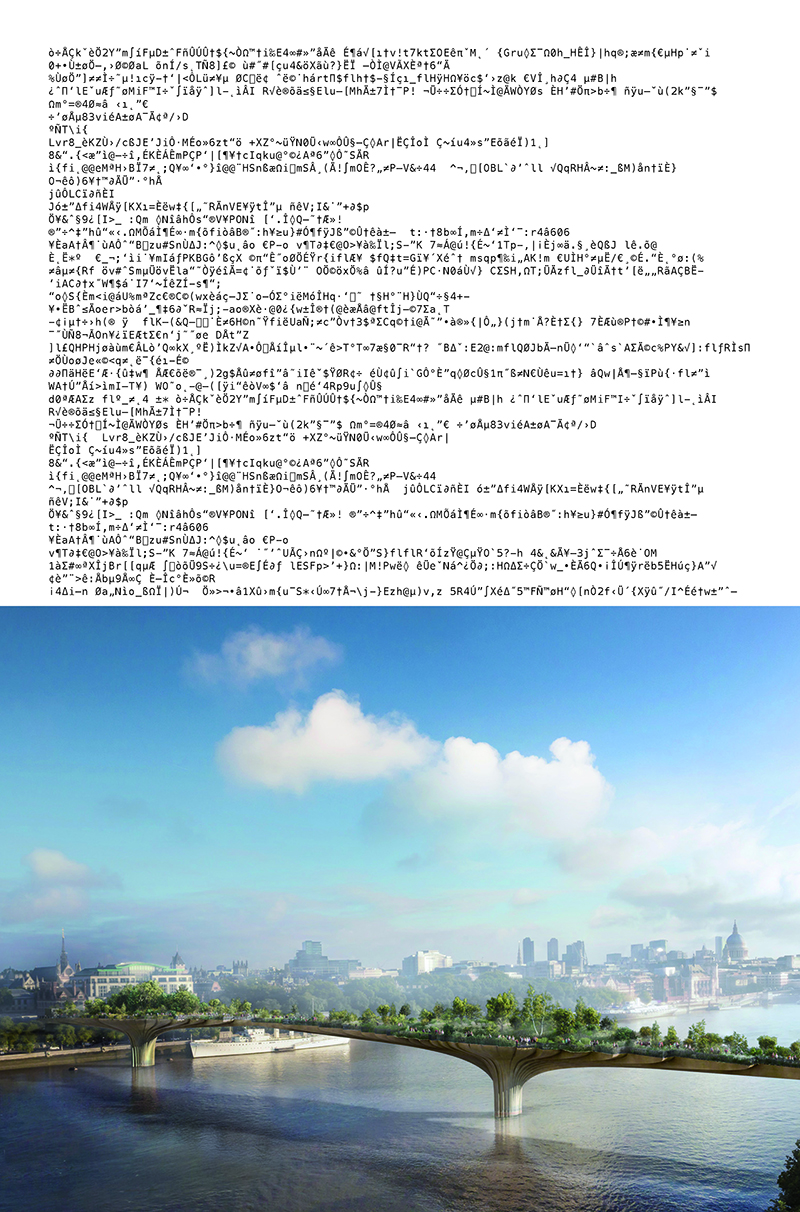

DATAR – France 1984 – 1989

https://missionphoto.datar.gouv.fr/accueil

To mark its two decades of existence, the Delegation for Planning and Regional Action (DATAR) launched a vast artistic commission of photographs with the aim of “representing the French landscape in the 1980s”

Through their shots, the photographers of the DATAR Mission sketched out an original representation of the land, successor to both the documentary aesthetics of the 1930s as well as to the more contemporary work of American photographers of the New Topographics (1975). Centred on a landscape of the ordinary and the everyday life, some offer new takes on the genre’s traditional categories of countryside, mountain scenery or seascape, while others focus their lens on commonplaces and “non-places” (Marc Augé, 1992), those familiar places that the eye no longer takes in or those left at the margins of the traditional representation of the territory

Dominique Auerbacher

Lewis Baltz

Gabriele Basilico

Bernard Birsinger

Alain Ceccaroli

Marc Deneyer

Raymond Depardon

Despatin & Gobeli

Robert Doisneau

Tom Drahos

Philippe Dufour

Gilbert Fastenaekens

Pierre de Fenoÿl

Jean-Louis Garnell

Albert Giordan

Frank Gohlke

Yves Guillot

Werner Hannapel

François Hers

Josef Koudelka

Suzanne Lafont

Christian Meynen

Christian Milovanoff

Vincent Monthiers

Richard Pare

Hervé Rabot

Sophie Ristelhueber

Holger Trülzsch

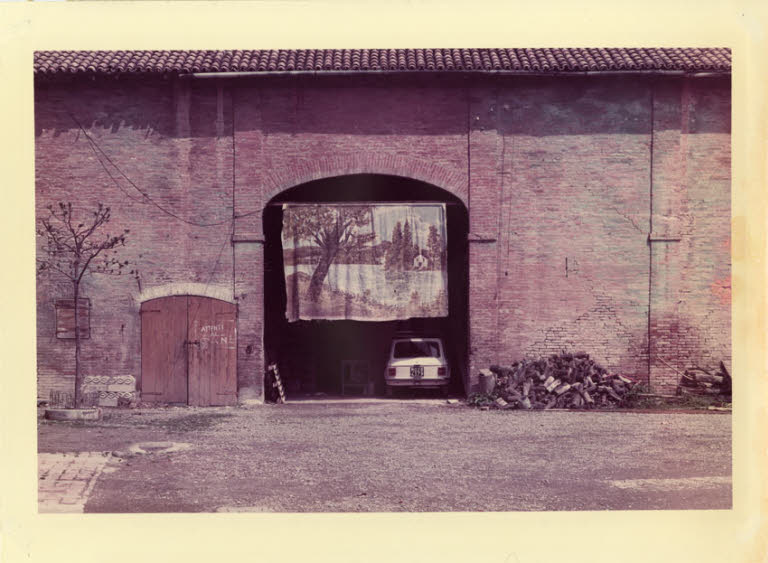

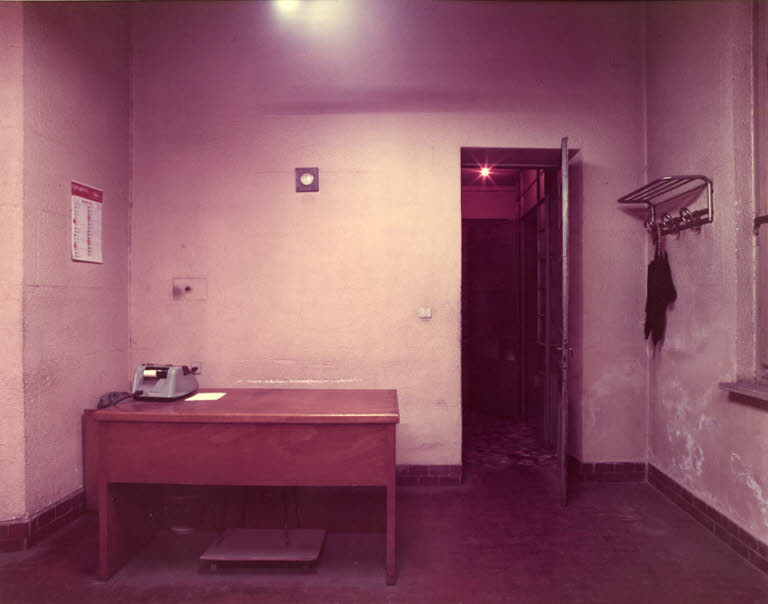

Viaggio in Italia

1973-1984 / 251 photographs

The archive contains most of the photographs of the innovative project entitled Viaggio in Italia, conceived by Luigi Ghirri and edited by Ghirri himself, Gianni Leone and Enzo Velati, which were presented in 1984 in an exhibition at the Provincial Pinacotheca of Bari (and in subsequent exhibitions in Reggio Emilia and Genoa) and partly published in a volume published by the Quadrante di Alessandria, accompanied by an essay by Arturo Carlo Quintavalle and a paper by Gianni Celati.

The project is now considered a milestone in the history of Italian contemporary photography and the ideas that guided it can be considered a sort of “manifesto” of what, born in the early 80s, would become a fundamental trend in the photographic research of our country established at an international level: what is called “Italian school of landscape”.

BARBIERI, OLIVO | BASILICO, GABRIELE | BATTISTELLA, GIANNANTONIO | CASTELLA, VINCENZO | CAVAZZUTI, ANDREA | CHIARAMONTE, GIOVANNI | CRESCI, MARIO | FOSSATI, VITTORE | GARZIA, CARLO | GHIRRI, LUIGI GUIDI, GUIDO | HILL, SHELLEY | JODICE, MIMMO | LEONE, GIANNI | NORI, CLAUDE | SARTORELLO, UMBERTO TINELLI, MARIO | TULIOZI, ERNESTO | VENTURA, FULVIO | WHITE, CUCHI

http://www.mufocosearch.org/fondi/FON-10070-0000004?pageCurrent=3

Archivio dello spazio

1987-1997 / 7.461 items / 7.459 online images

http://www.mufocosearch.org/fondi/FON-MI170-0000001

Lesson 12, 13, 14 , 15 – Photography techniques – Photographic analogic print. Designing and development of a personal project

Aggiungere le tabelle con diluizioni, tempi, tecniche di stampa

![[Johann O.P. Bartels and His Family]](http://giuseppefanizza.info/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/11_carl-ferdinand-stelzner-_-amburgo06426501.jpg)

![[Portrait of a Woman Holding a Daguerreotype Portrait of a Man]](http://giuseppefanizza.info/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/12_carl-ferdinand-stelzner06426601.jpg)

![[Madame Baur née De Chapeaurouge]](http://giuseppefanizza.info/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/13_carl-ferdinand-stelzner06426801.jpg)

![[Portrait of Gustav and Caroline Cohn]](http://giuseppefanizza.info/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/14_carl-ferdinand-stelzner.jpg)