Travel Photography in Rome

tuesday july 26th – INTRODUCTION

Landscape Photography, Travels, Explorations

The first subject targeted by photographers was the landscape, both for the technical limit of long exposure times, and for the wonder of technological progress that the observer of an image felt at the dawn of his invention. The pure intention and technology of creating an optical image was sufficient to justify it and motivated its use. The mere looking was in itself surprising.

Just few days after the release of the invention on 19 August, the magazine Le Lithographe published a lithograph from a daguerreotype (this was for some years the standard process of replication of images obtained with daguerreotype, beyond the only positive original).

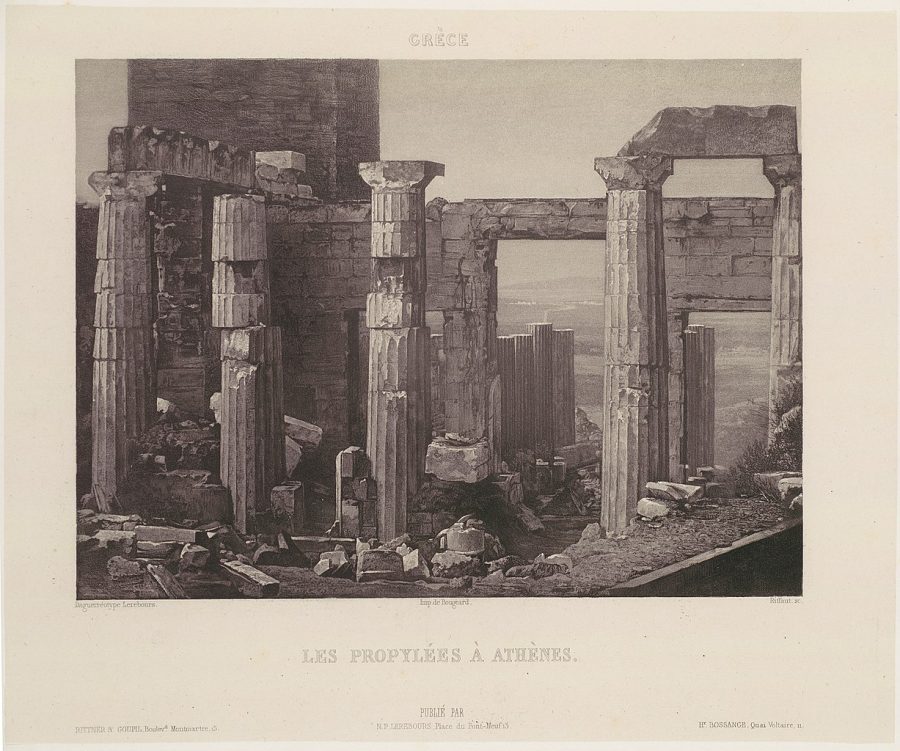

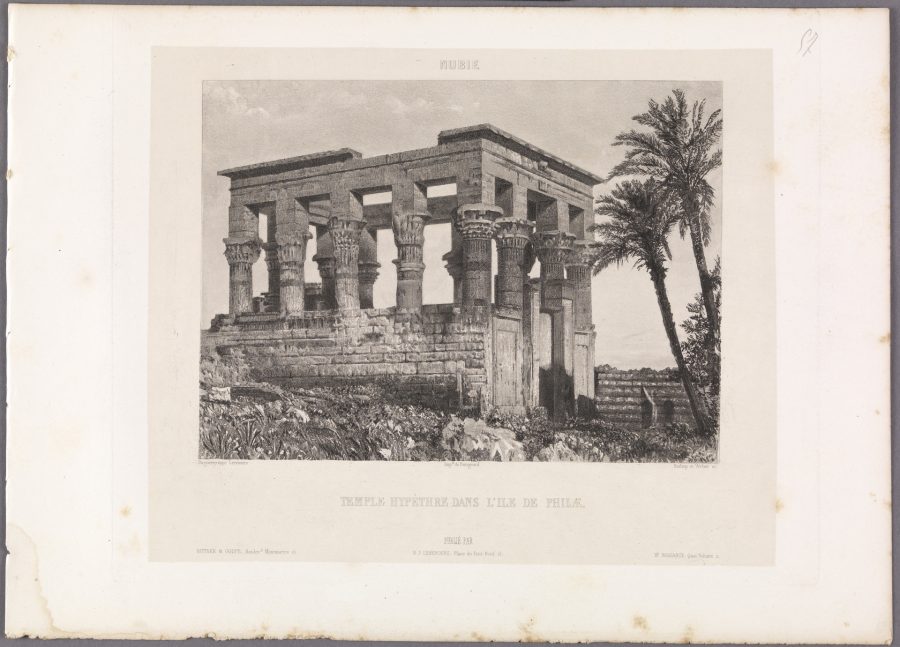

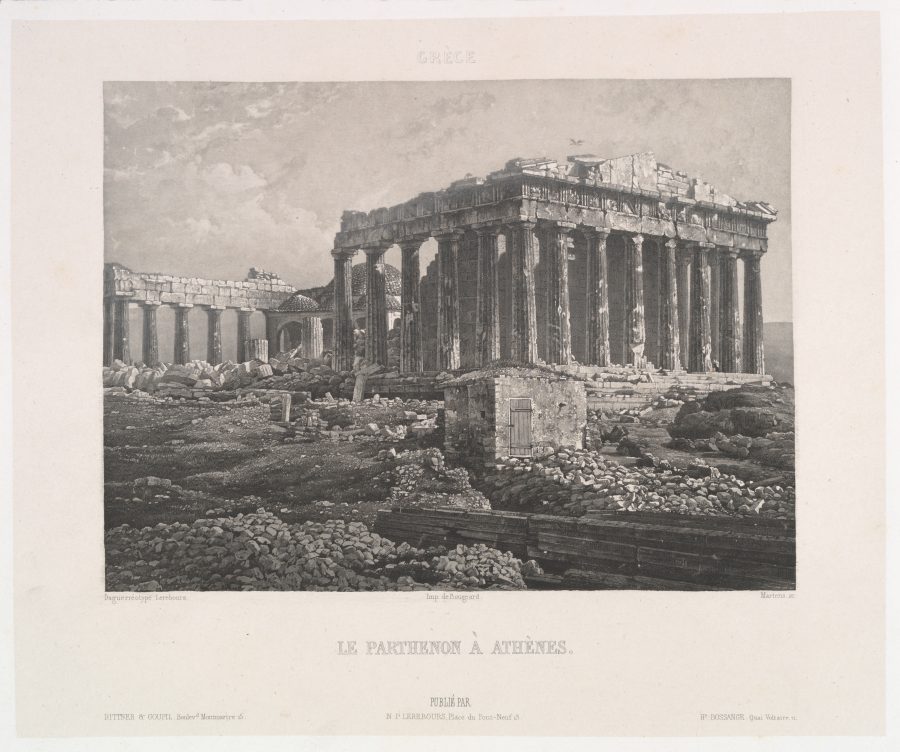

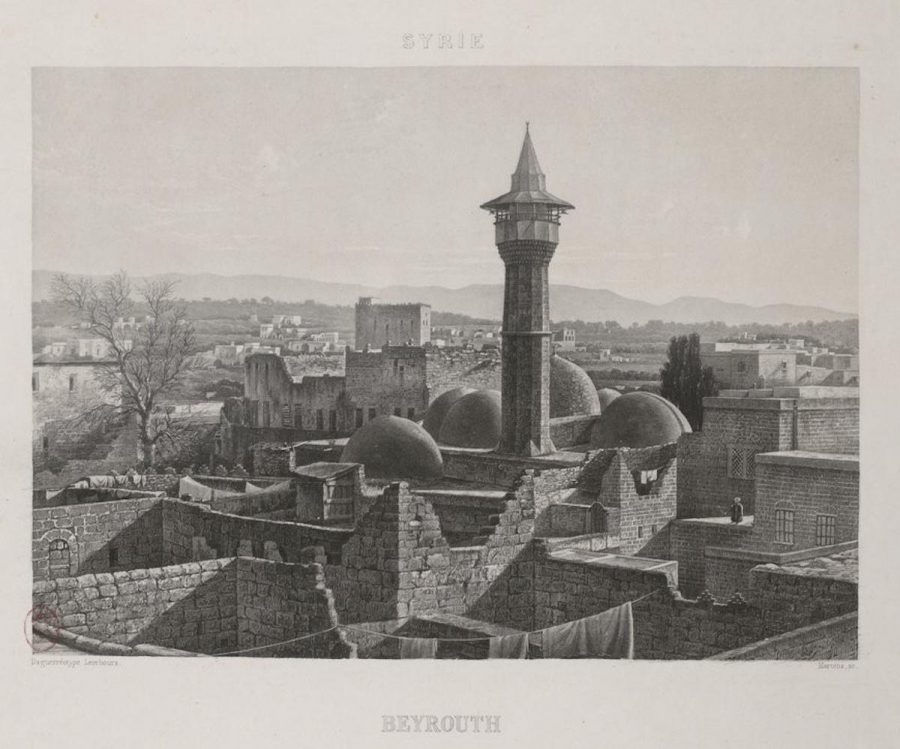

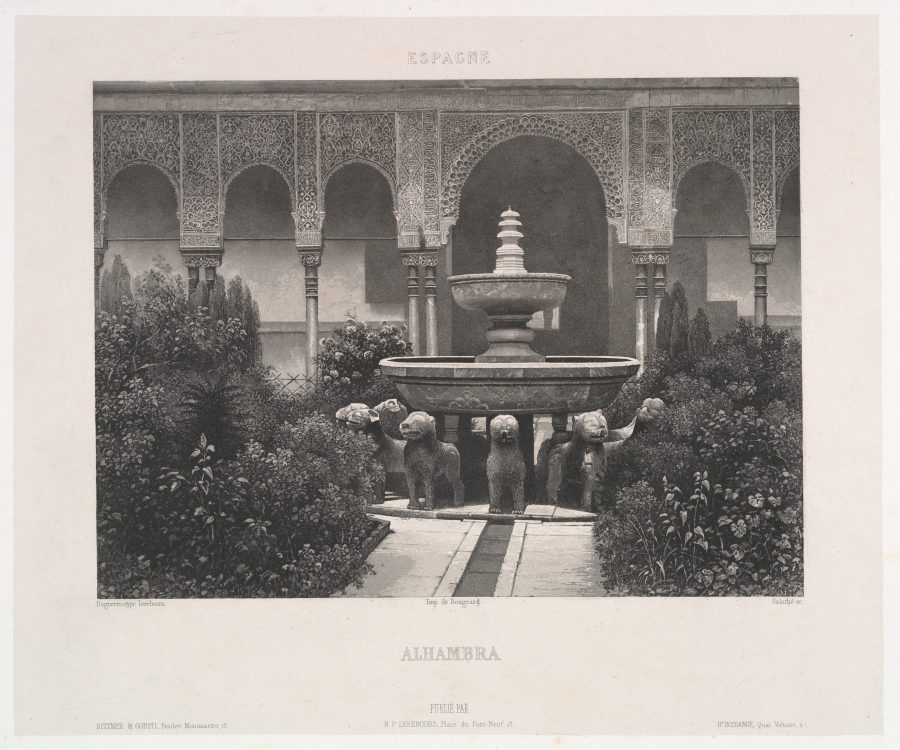

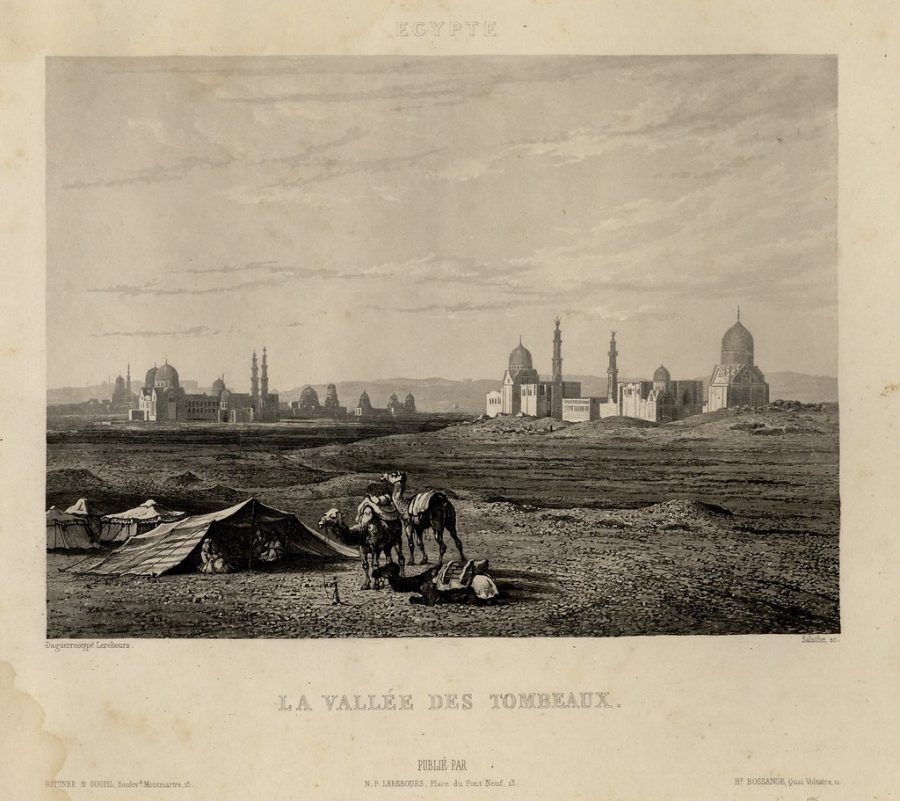

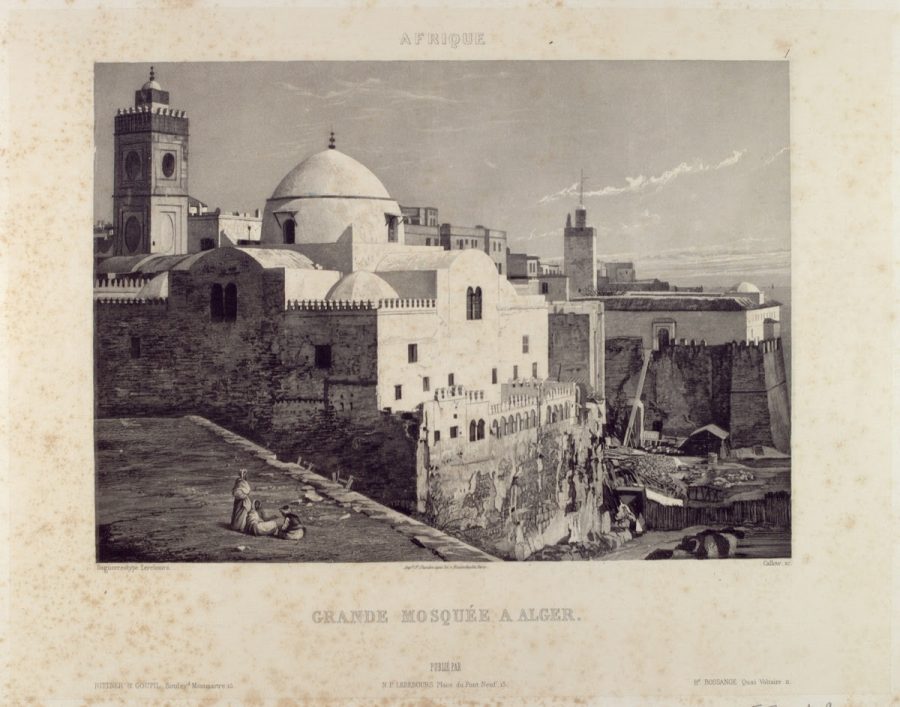

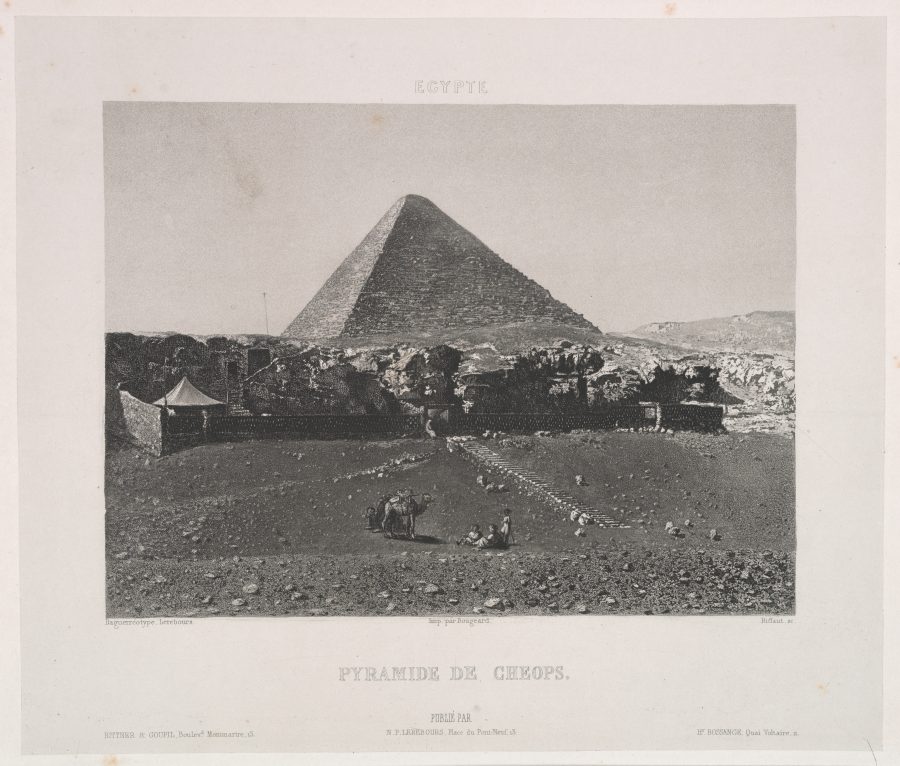

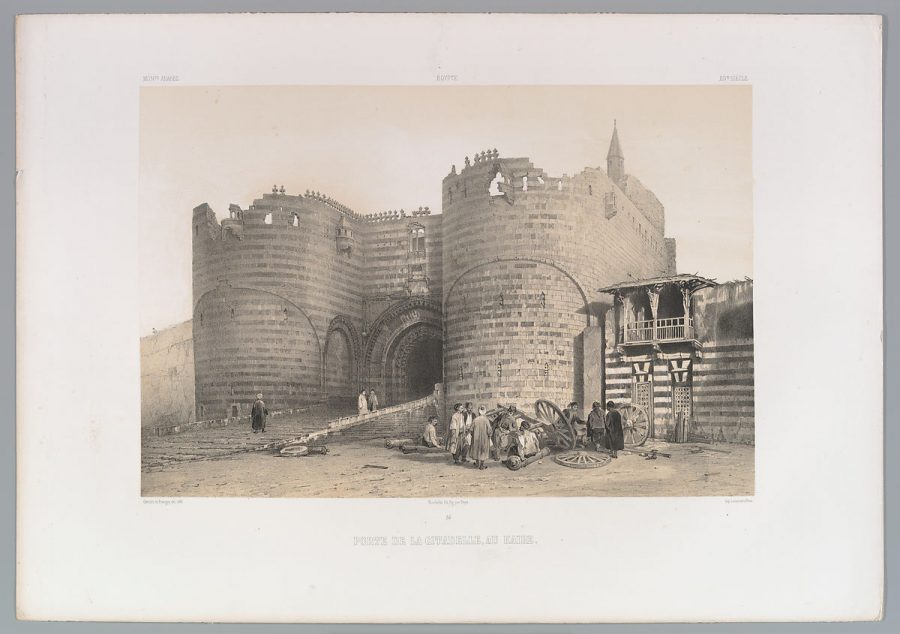

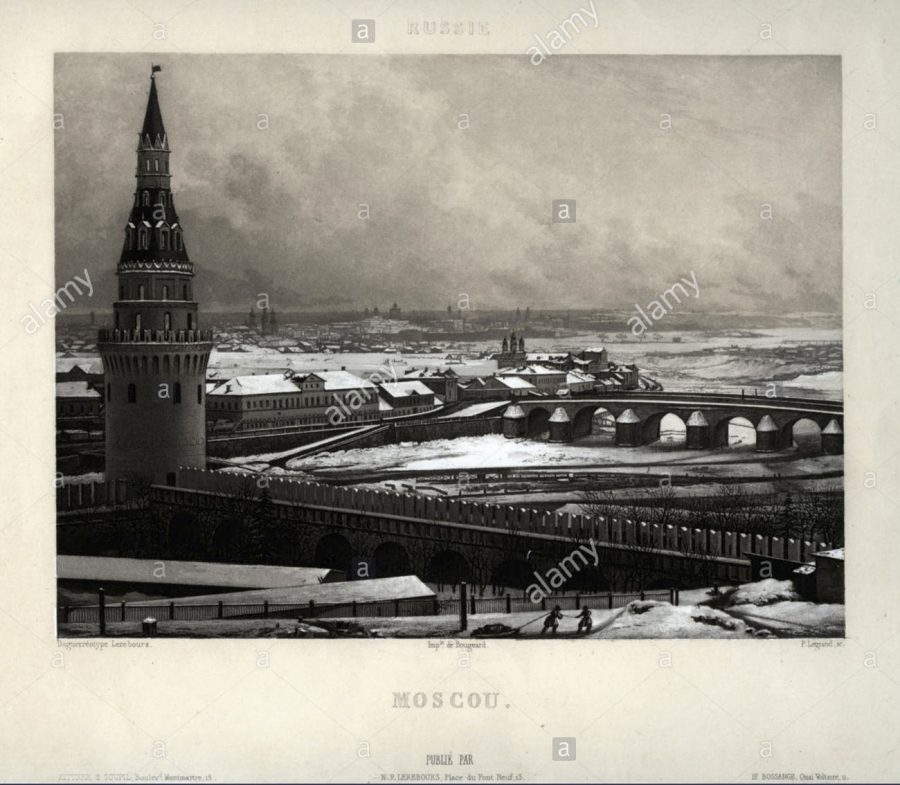

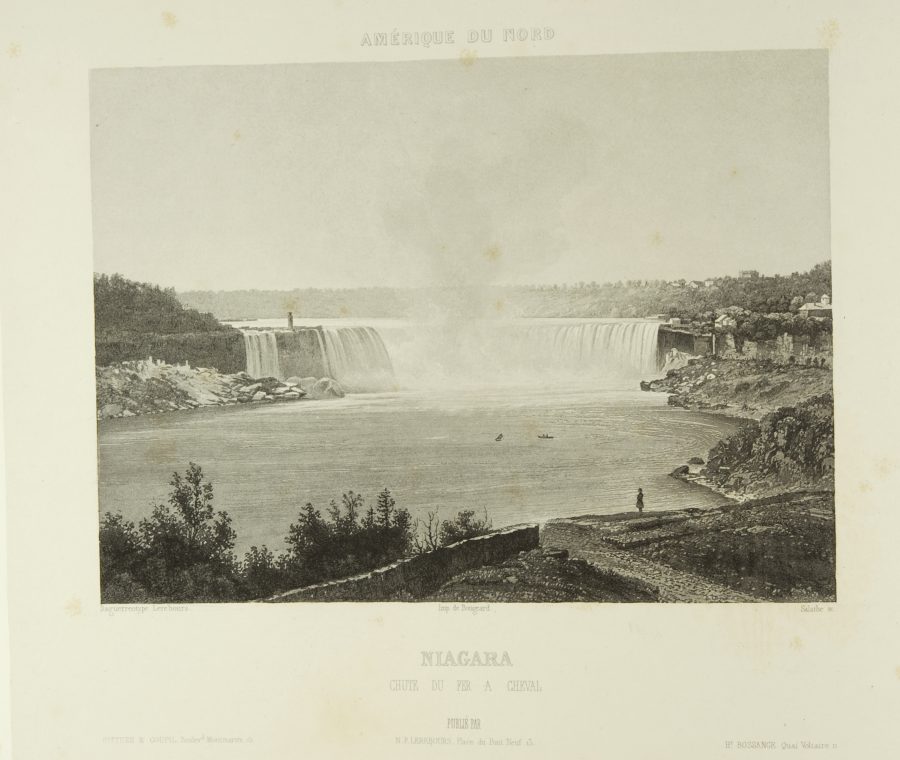

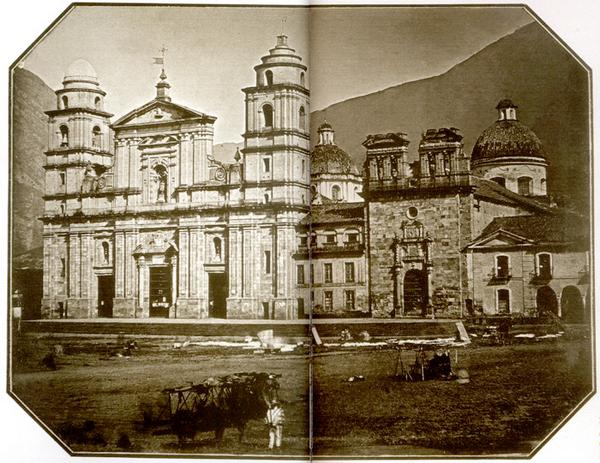

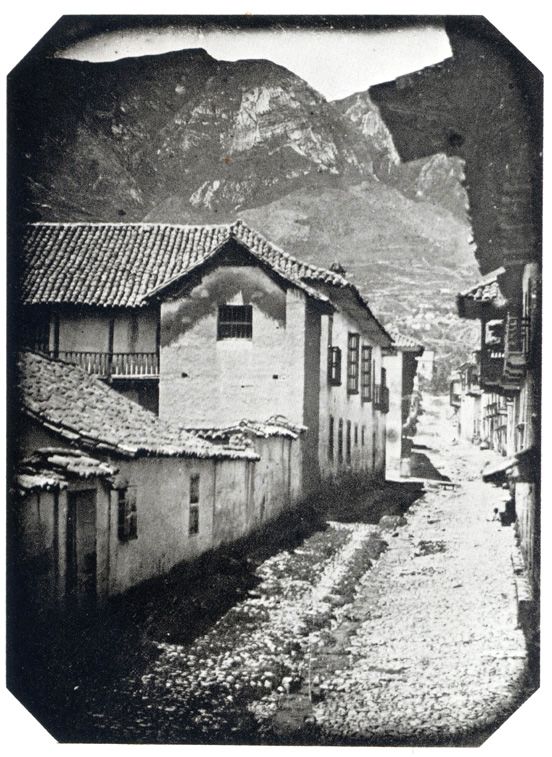

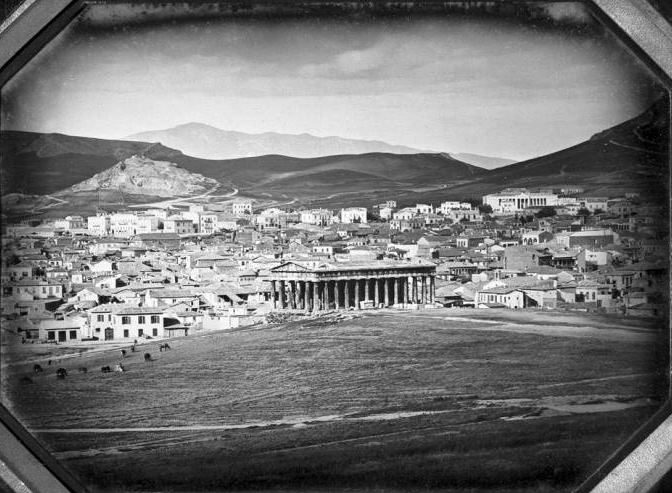

Between 1840 and 1844 the publisher Lerebours published a series of topographical views called Excursions Daguerriennes, 114 views from Europe, the Middle East and America, enriched with the addition of human figures designed to make up for the feeling of abandonment that was perceived by the absence of people.

Louis Blanquart-Evrard in 1850 designed a printing paper that reduced the printing time of a copy to 6 – 15 seconds. He covered the paper with egg whites in which potassium bromide and acetic acid were dissolved. Once dry, it was agitated in a silver nitrate solution and re-dried. The prepared sheet was superimposed on the negative and exposed to the sun. His Imprimeriè Photographique by Lille was able to produce high runs of “Album photographique”.

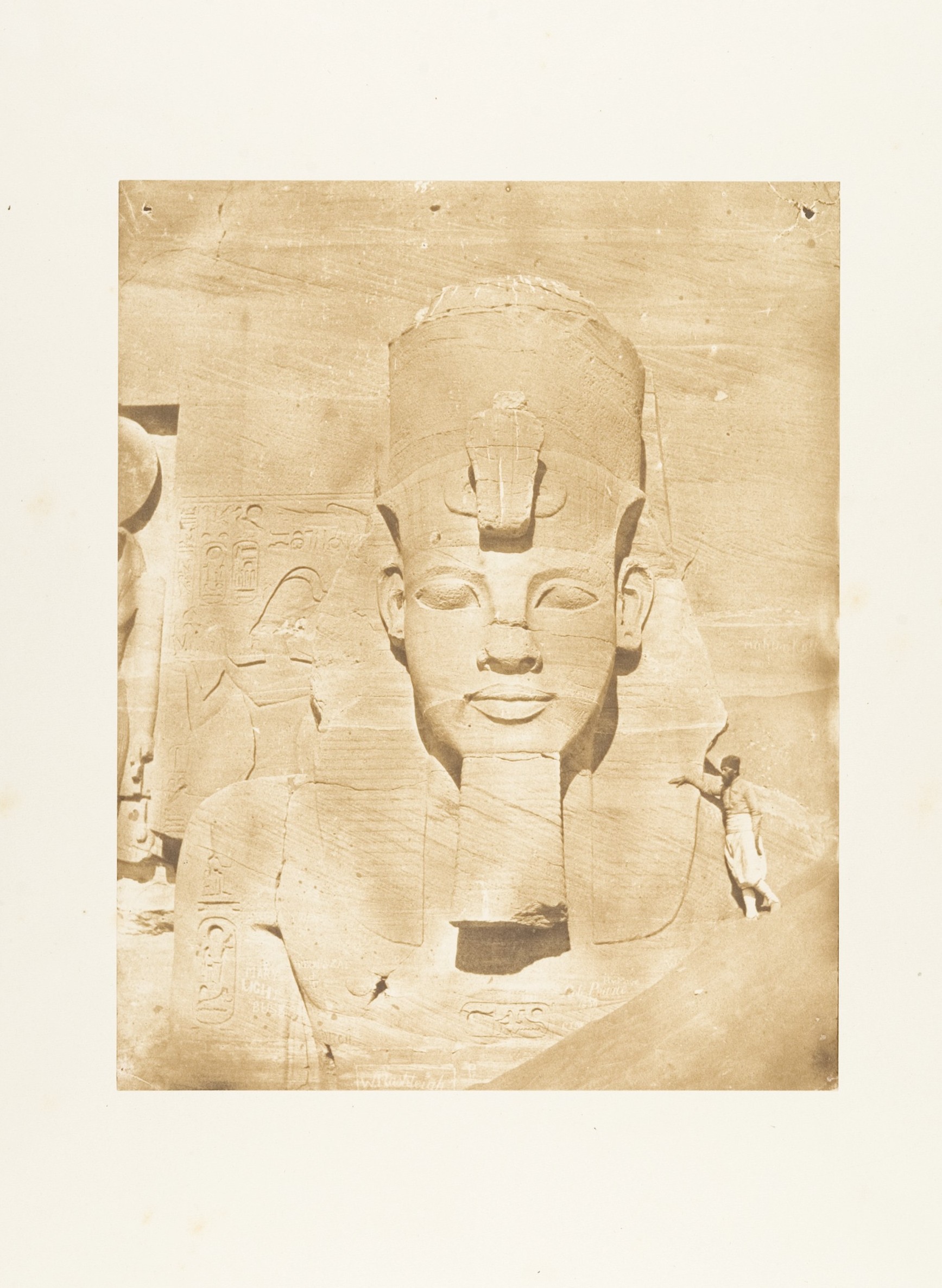

His masterpiece was “Egypte, Nubie, Palestine, et Syrie” containing 122 photos of Maxime Du Camp, a scholar who had travelled to the Middle East between 1849 and 1852, along with Gustave Flaubert.

“I lost precious time in drawing the monuments or views that I wanted to remember,” explained Du Camp. “I drew slowly and in an incorrect manner. I understood that I needed a precision instrument to bring back images that would allow me to make exact reconstructions,”

Blanquart-Evrard also published calotypes (it was the brand new technique designed by Henry Fox Talbot) made along the Nile by John B. Greene (°°°), Henri Le Secq (°°°), Charles Negre (°°°).

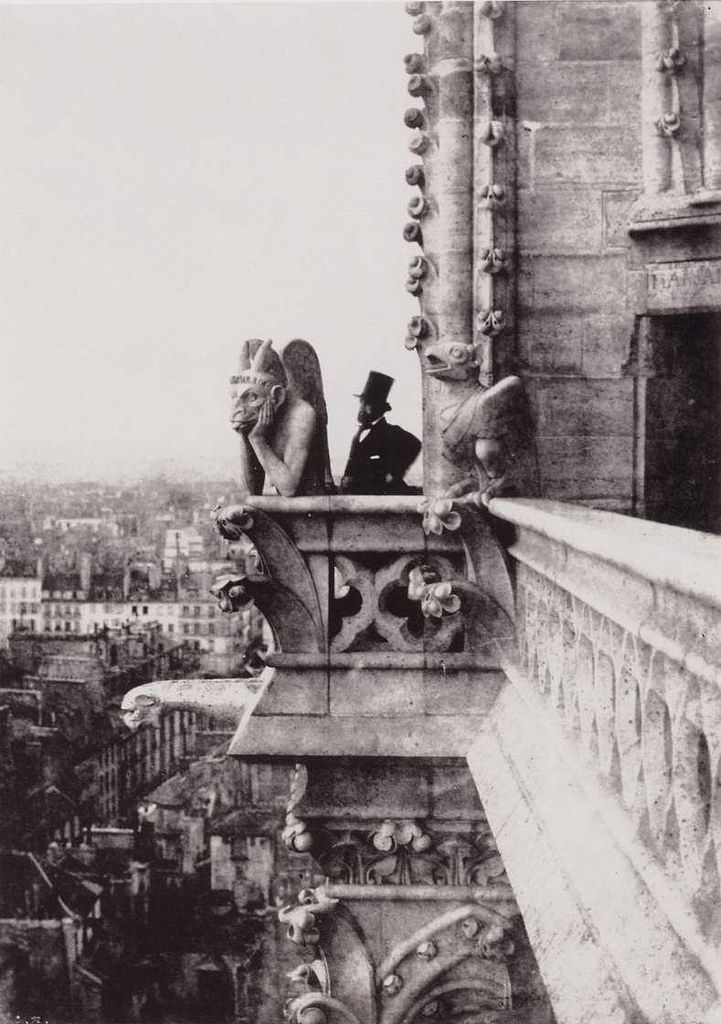

The latter photographed his friend Le Secq on the terrace of Notre Dame in 1851:

1851 Mission Héliographique (collodion & calotype)

In 1851, the Commission des Monuments Historiques, an agency of the French government, selected five photographers to make photographic surveys of the nation’s architectural patrimony. These Missions Héliographiques, as they were called, were intended to aid the Paris-based commission in determining the nature and urgency of the preservation and restoration of work required at historic sites throughout France.

The selected photographers—Édouard Baldus , Hippolyte Bayard, Gustave Le Gray , Henri Le Secq, and Auguste Mestral—were all members of the fledgling Société Héliographique, the first photographic society. Each was assigned a travel itinerary and detailed list of monuments. Baldus was sent south and east to photograph the Palace of Fontainebleau , the medieval churches of Lyon and other towns in the Rhône valley, and the Roman monuments of Provence, including the Pont du Gard, the triumphal arch at Orange, the Maison Carrée in Nîmes, and the amphitheater at Arles.

Gustave Le Gray, already recognized as a leading figure on both the technical and artistic fronts of French photography, was sent southwest, to the famed châteaux of the Loire Valley—Blois, Chambord, Amboise, and Chenonceaux, among others—to the small towns and Romanesque churches along the pilgrimage routes to Santiago de Compostela, and through the Dordogne. Le Gray traveled with Mestral and photographed sites on his old friend and protégé’s list, including the fortified town of Carcassonne (not yet “restored” by Viollet-le-Duc), Albi, Perpignan, Le Puy, Clermont-Ferrand, and other sites in south-central and central France. On occasion, the two worked hand-in-hand, for a few photographs are signed by both photographers.

Henri Le Secq was sent north and east to the great Gothic cathedrals of Reims, Laon, Troyes, and Strasbourg, among others. And Hippolyte Bayard, the only one of the five to have worked with glass—rather than paper—negatives (and thus, the only one whose negatives no longer survive), was sent west to towns in Brittany and Normandy, including Caen, Bayeux, and Rouen.

https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/heli/hd_heli.htm

Google images Missions Héliographiques

War

The first war photography reportage is signed by Roger Fenton. One of the founders of the Photographic Society of London, he was commissioned by Queen Victoria to photograph the family and the royal house and later became the official photographer of the British Museum.

He was commissioned by prints merchants Thomas Agnew & Sons to photograph the Crimean War. As he used the wet collodion, Fenton equipped a photographic van with 700 glass plates and the rest of the photographic material.

After the Crimean war Robertson was embedded with Her Majesty Army and followed the Bengal revolts and later on the Second Opium War with assistant Felice Beato (who also was his brother in law).

After the war Beato continued his journey to China and Japan where he documented the local rural life and customs.

A similar work was carried out later (at the turn of 1900) by Edward Curtis with the Native Americans. Both iconographies heavily influenced literary and cinematic production on the Far East and the Far West to this day.

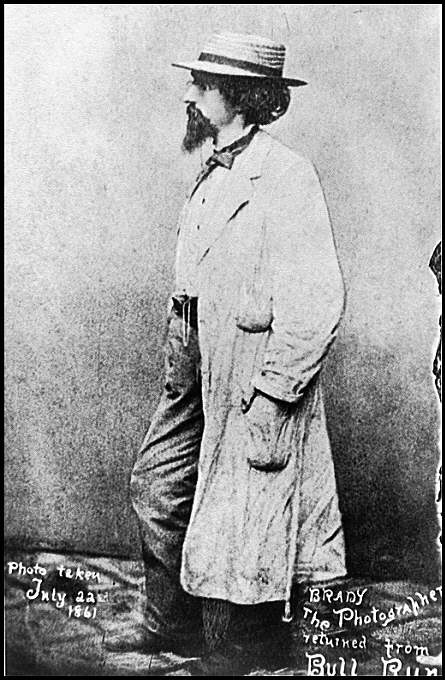

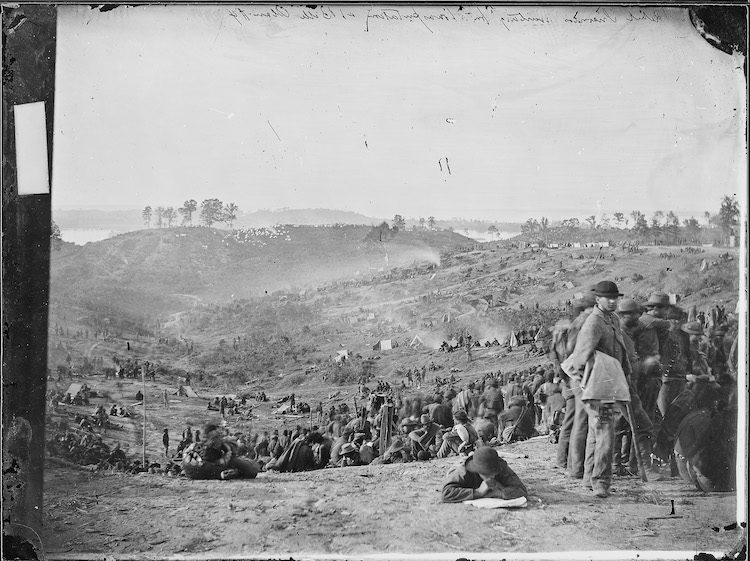

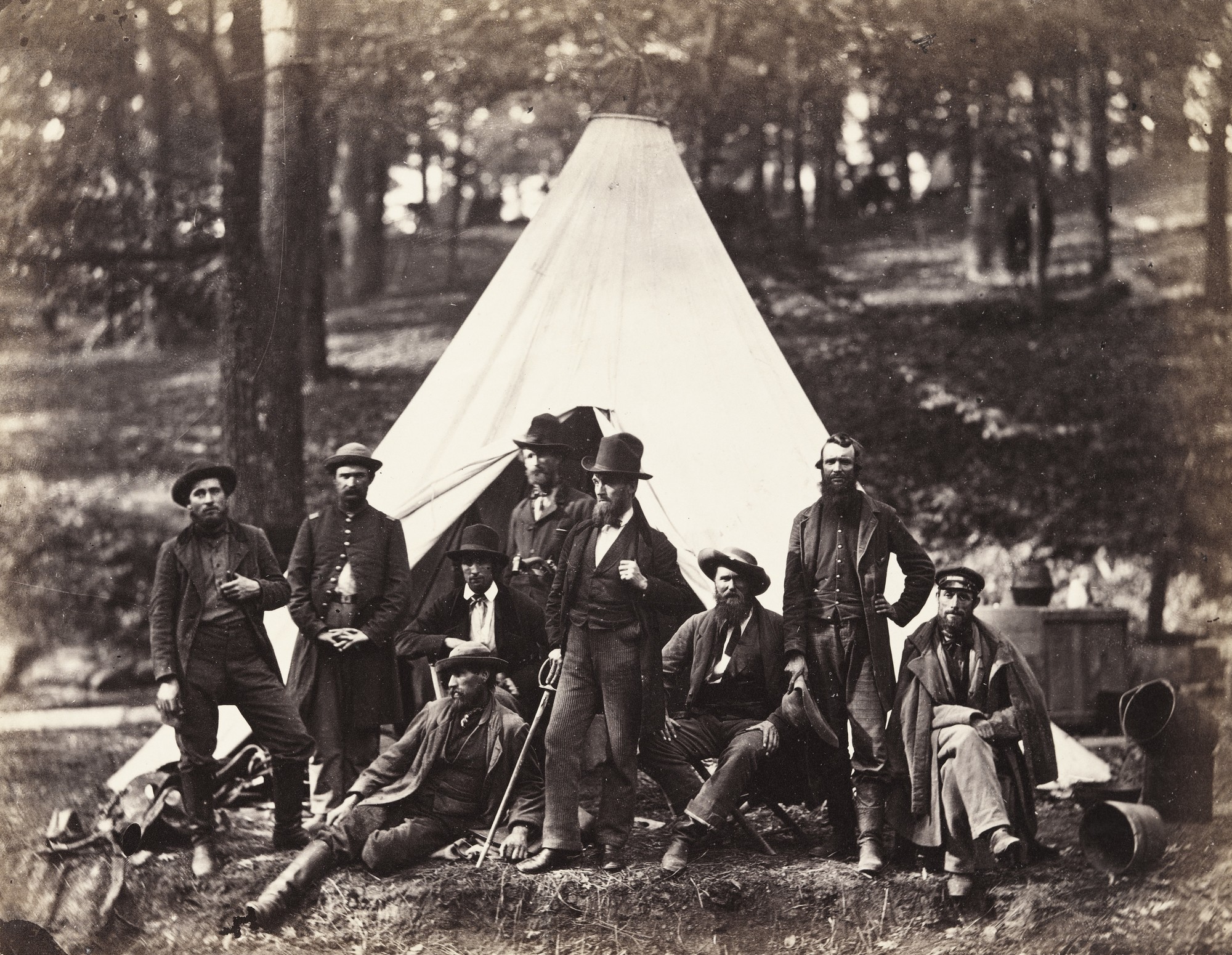

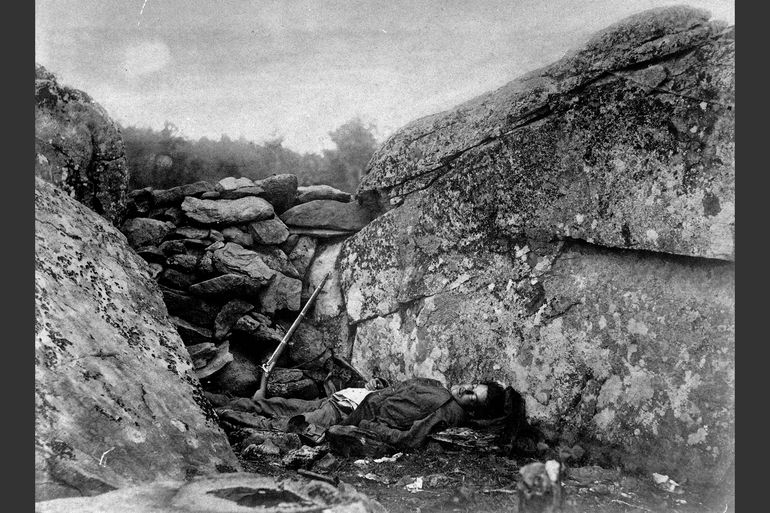

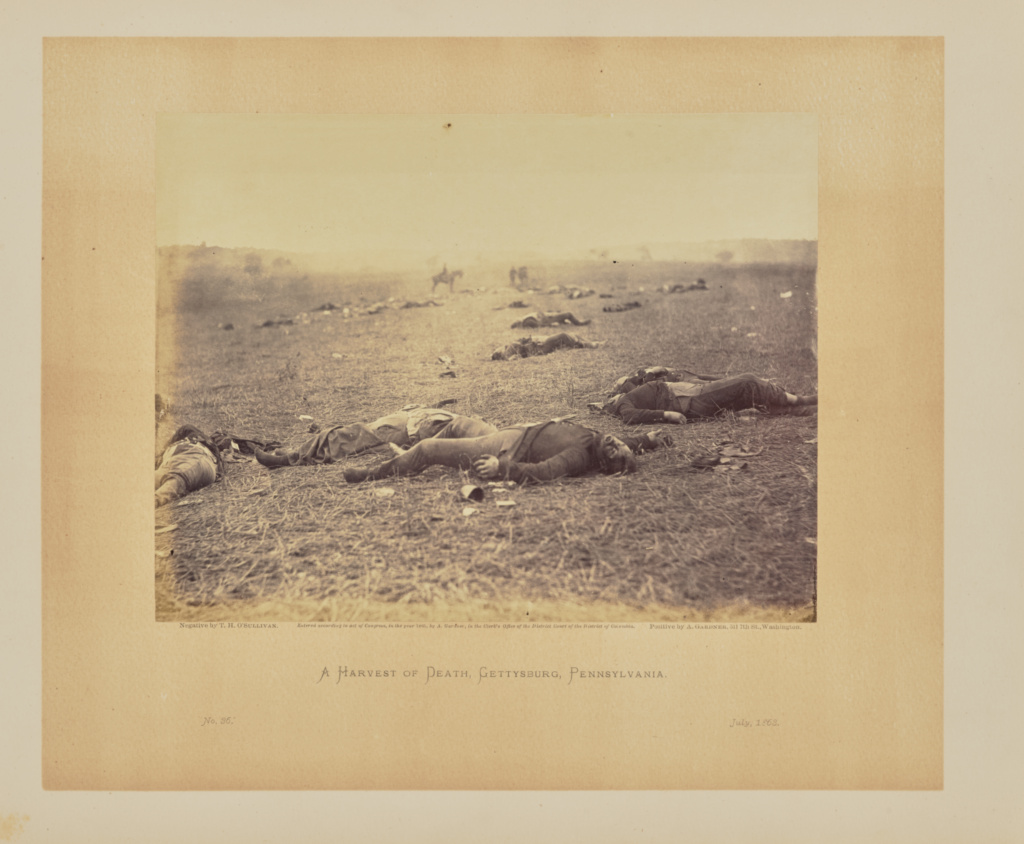

In 1861, when the American Civil War broke out, Brady organized a group of photographers to set out in the quest to photograph the war. His team included Alexander Gardner and Timothy O’Sullivan.

Exploration and progress

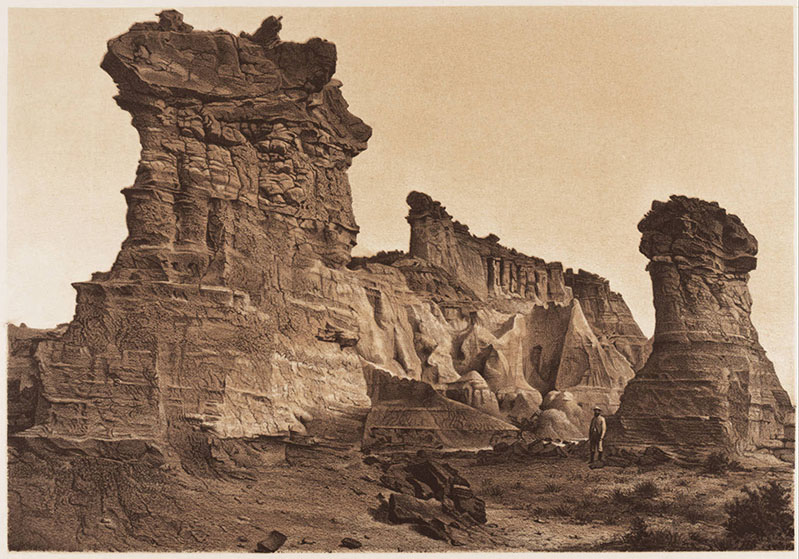

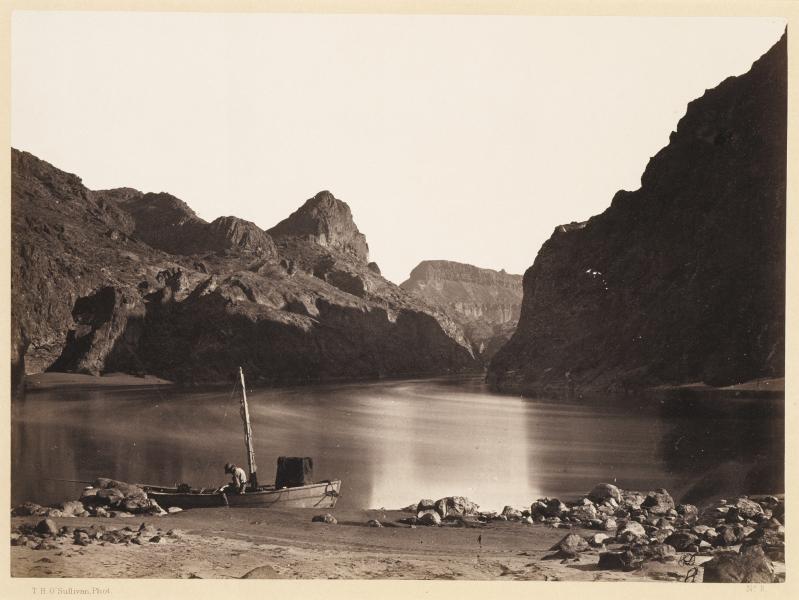

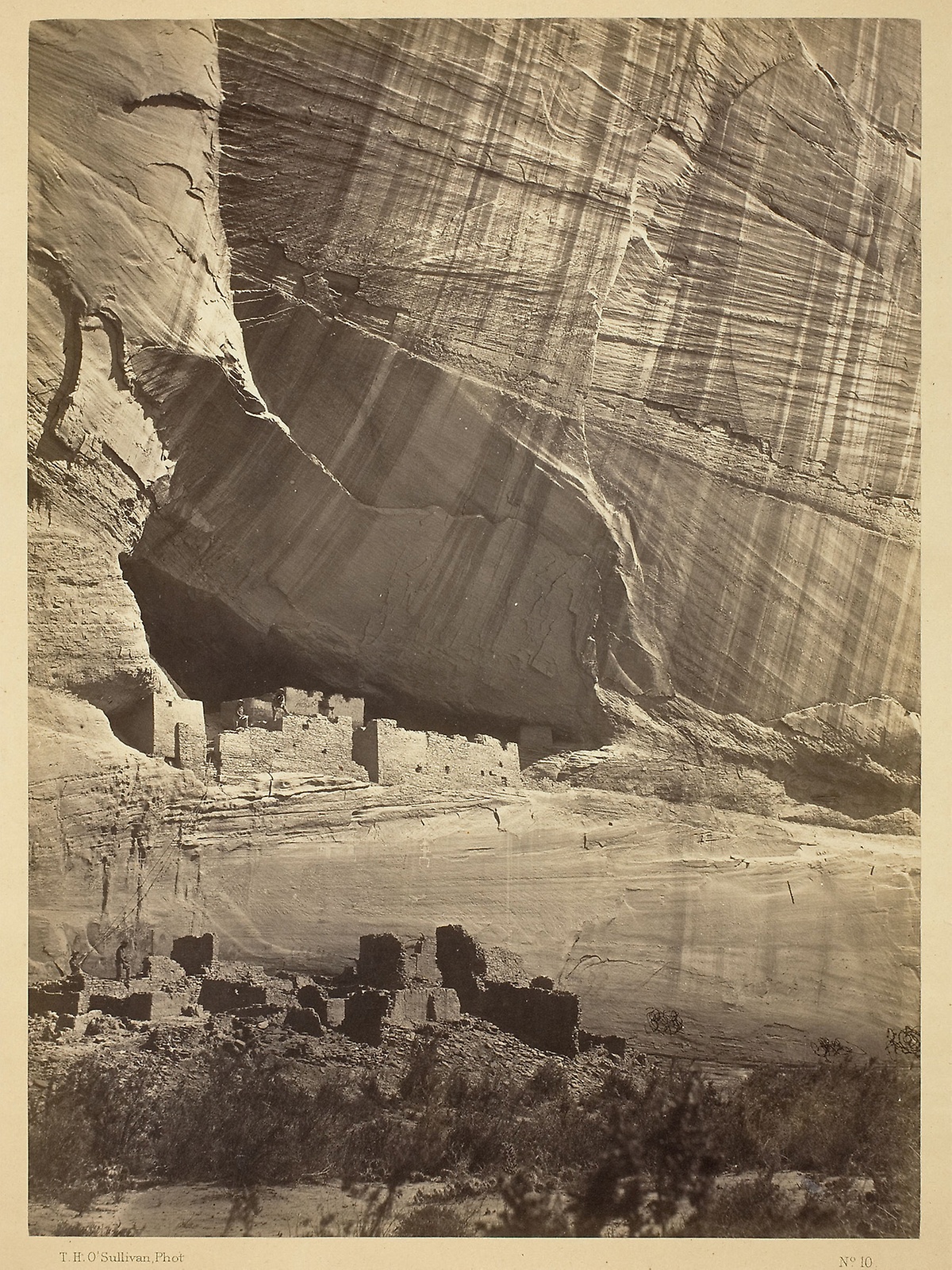

Many Civil War photographers later joined the army’s engineers engaged in paramilitary expeditions that later became official geographical surveys carried out for the United States government.

Fenton, Robertson, Beato and other early times war photographers had showed that images could be at great service of politics and empire.

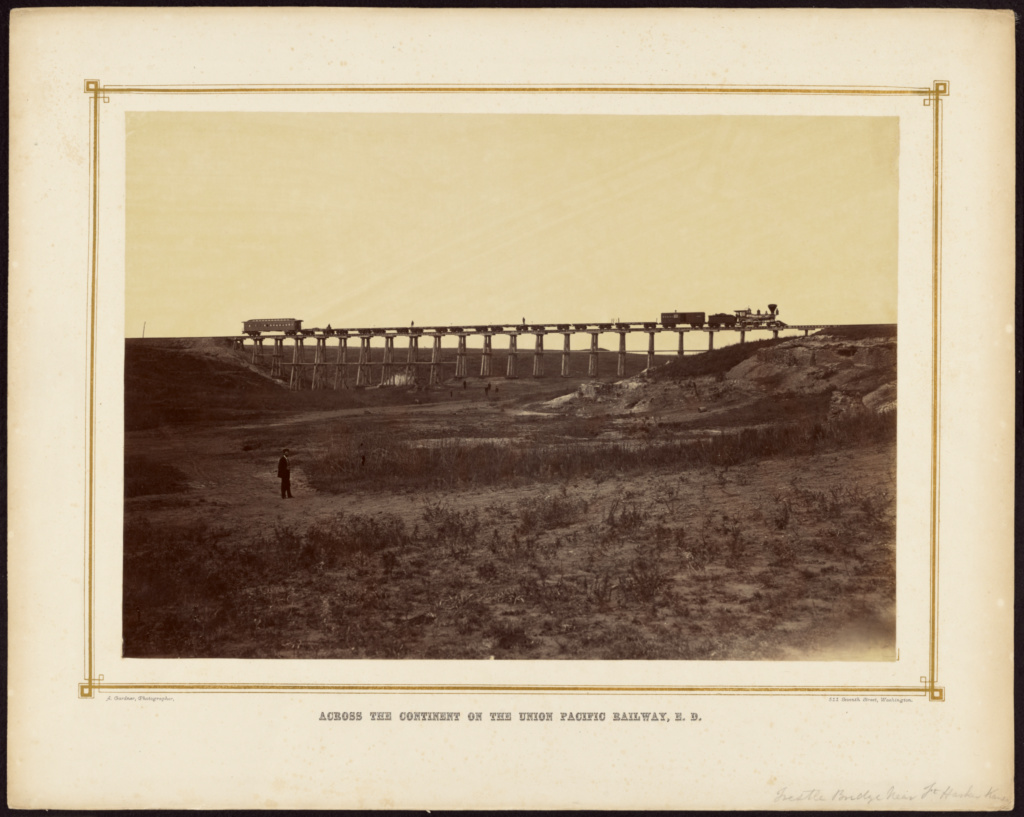

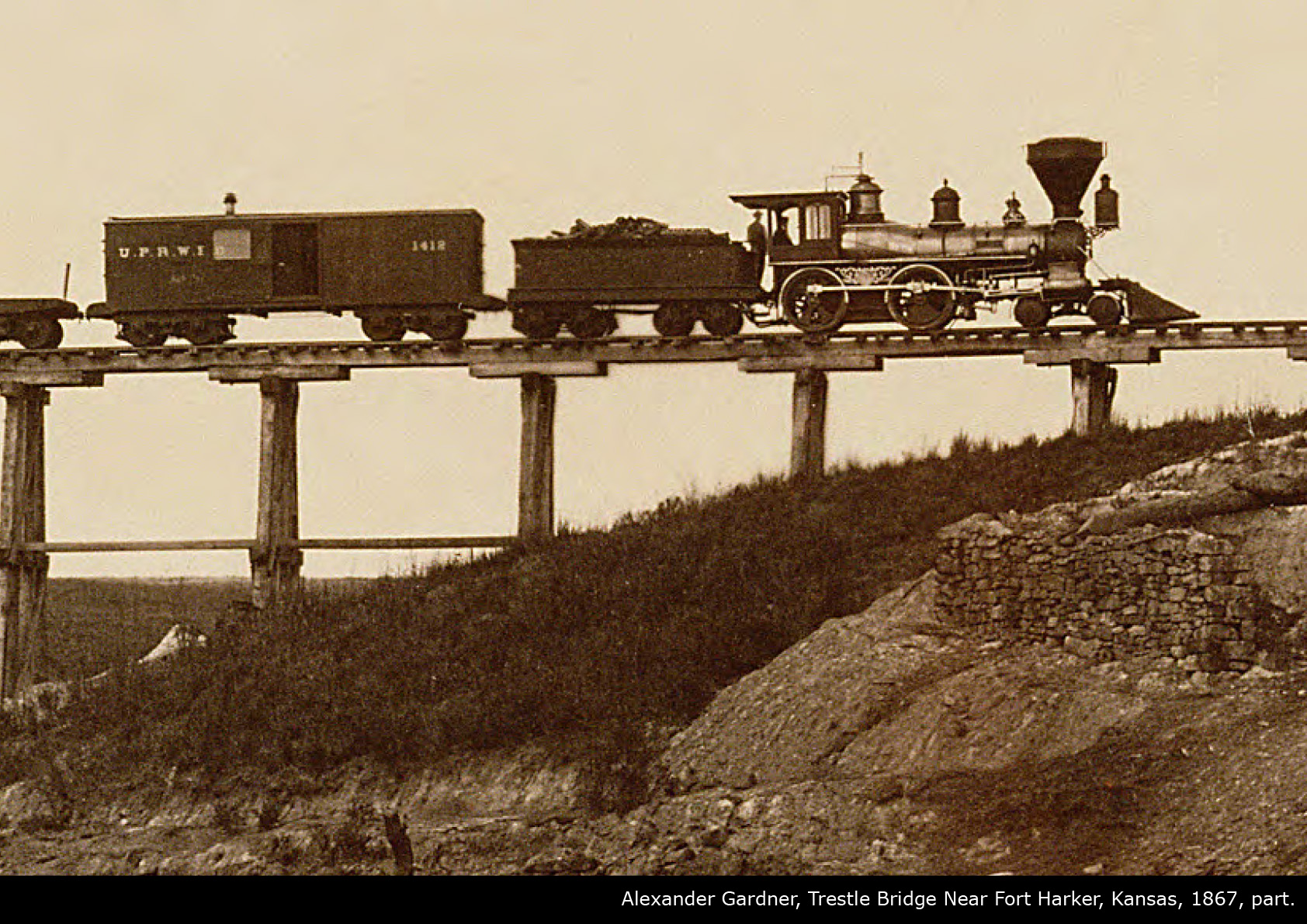

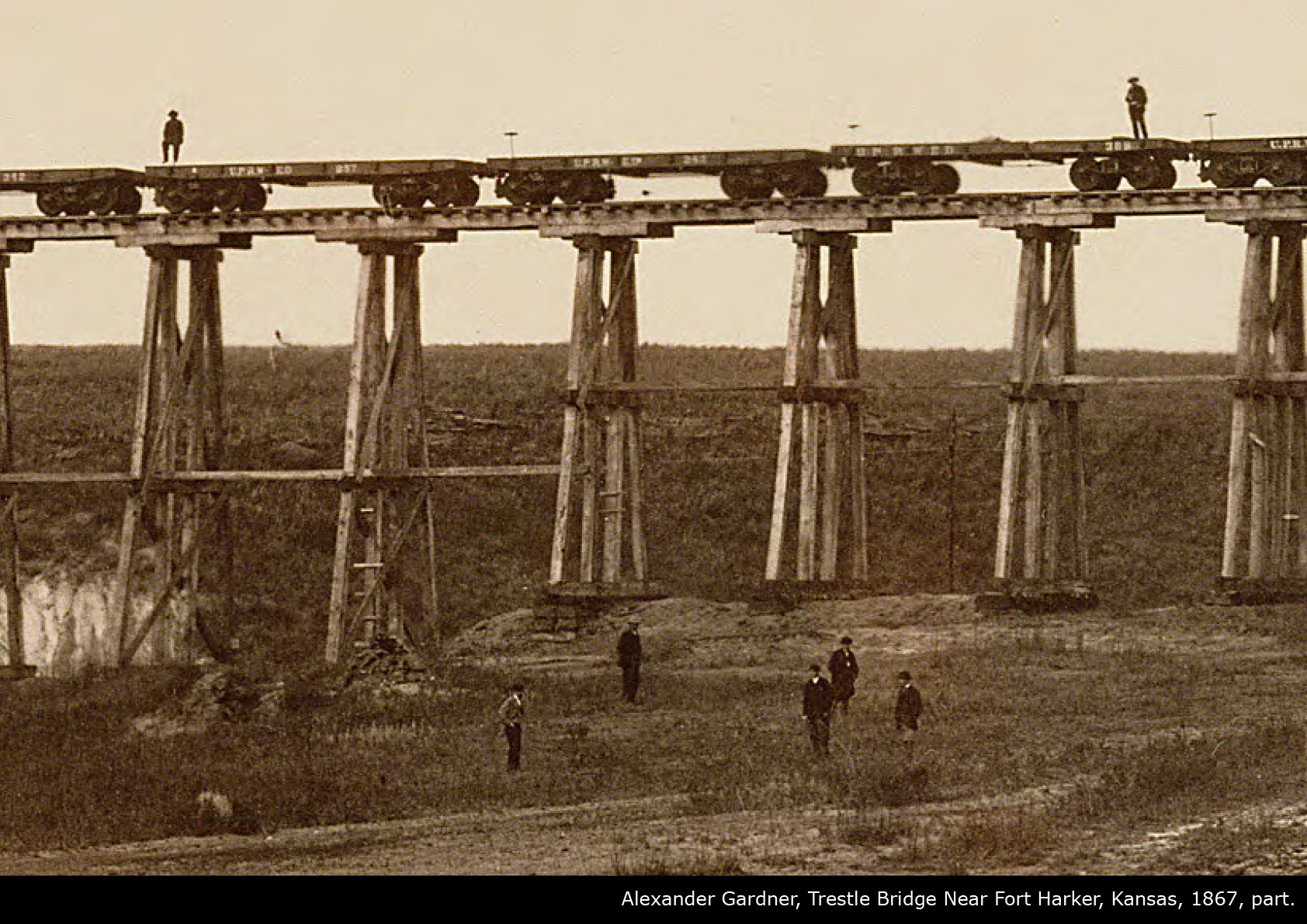

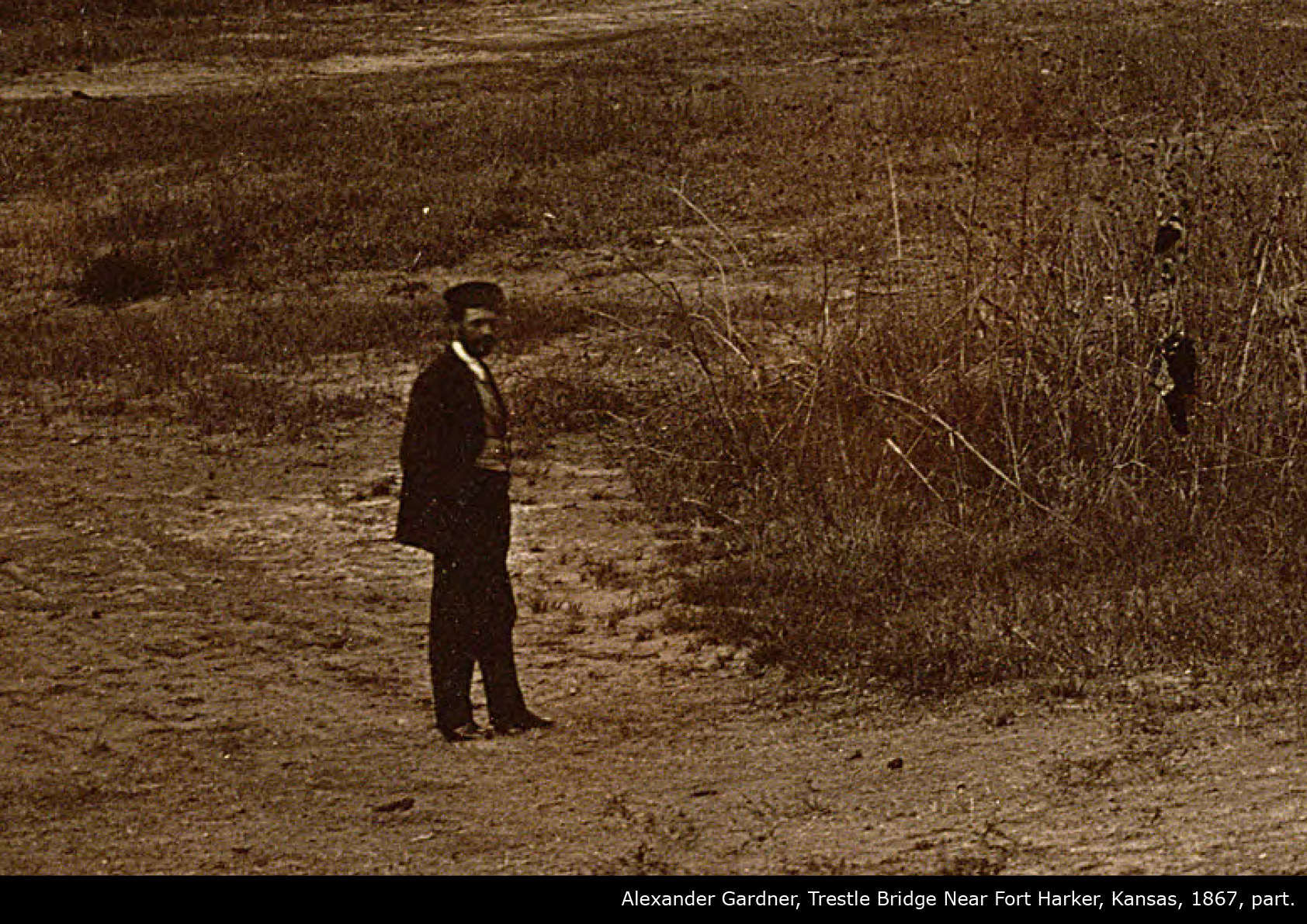

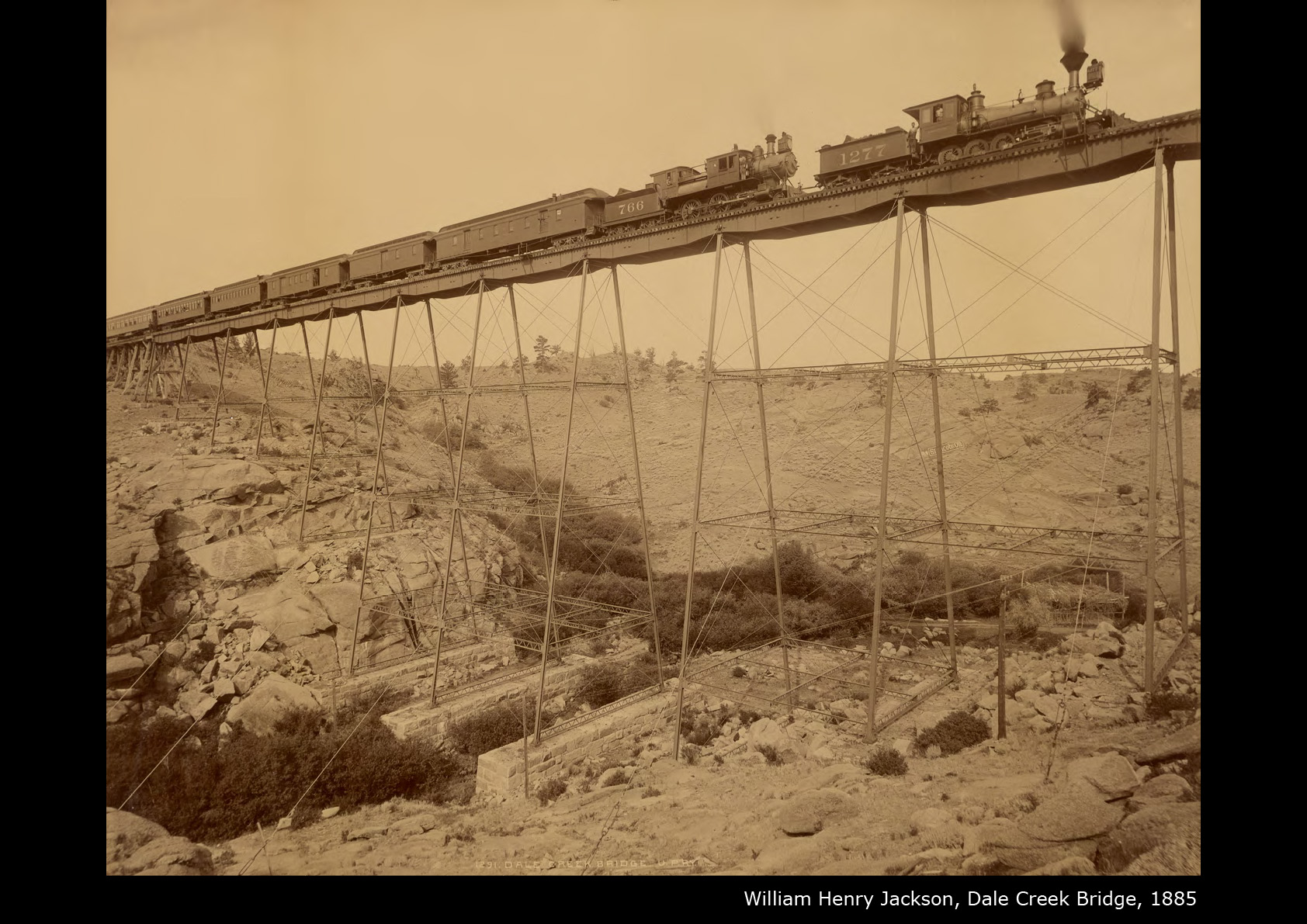

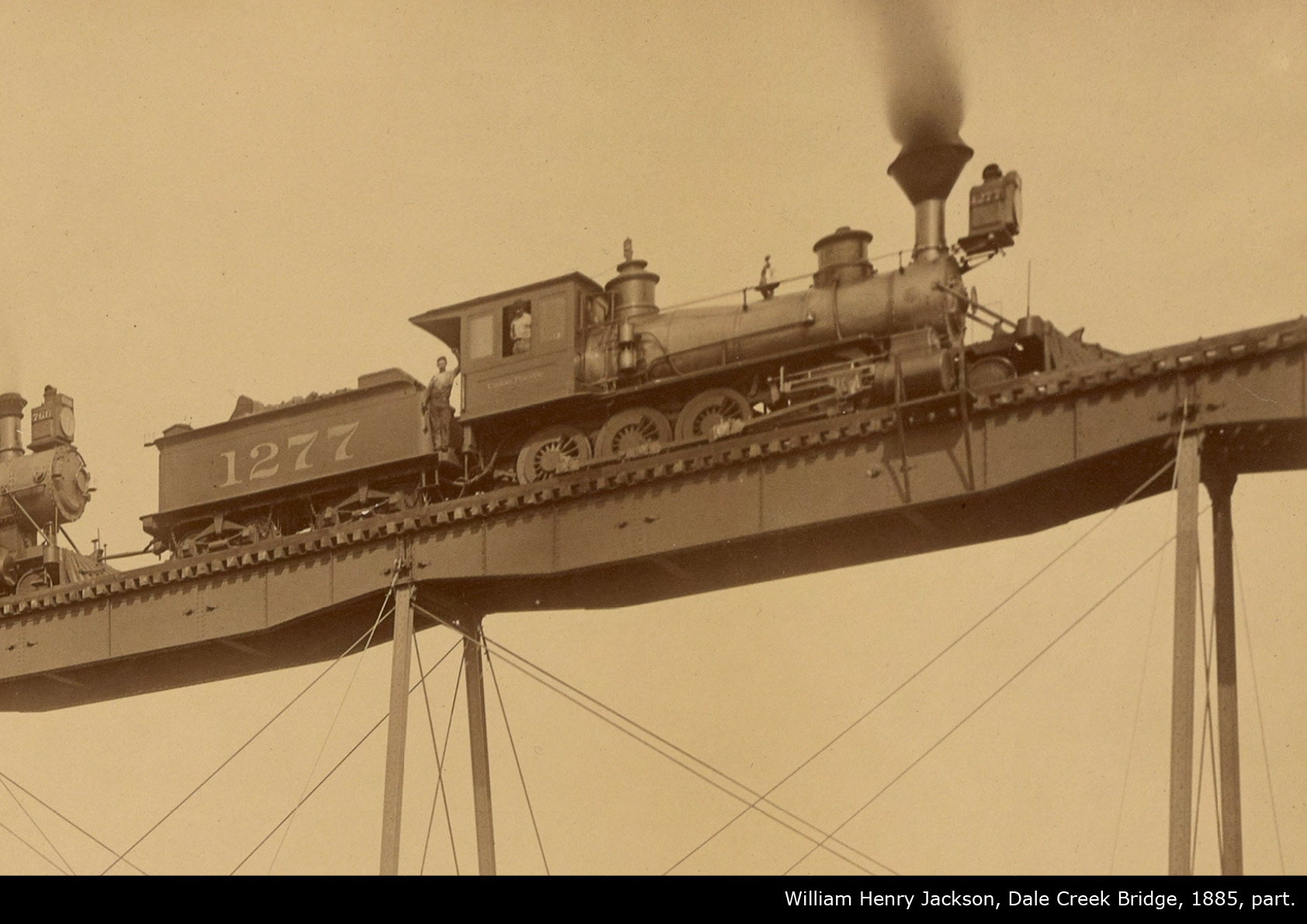

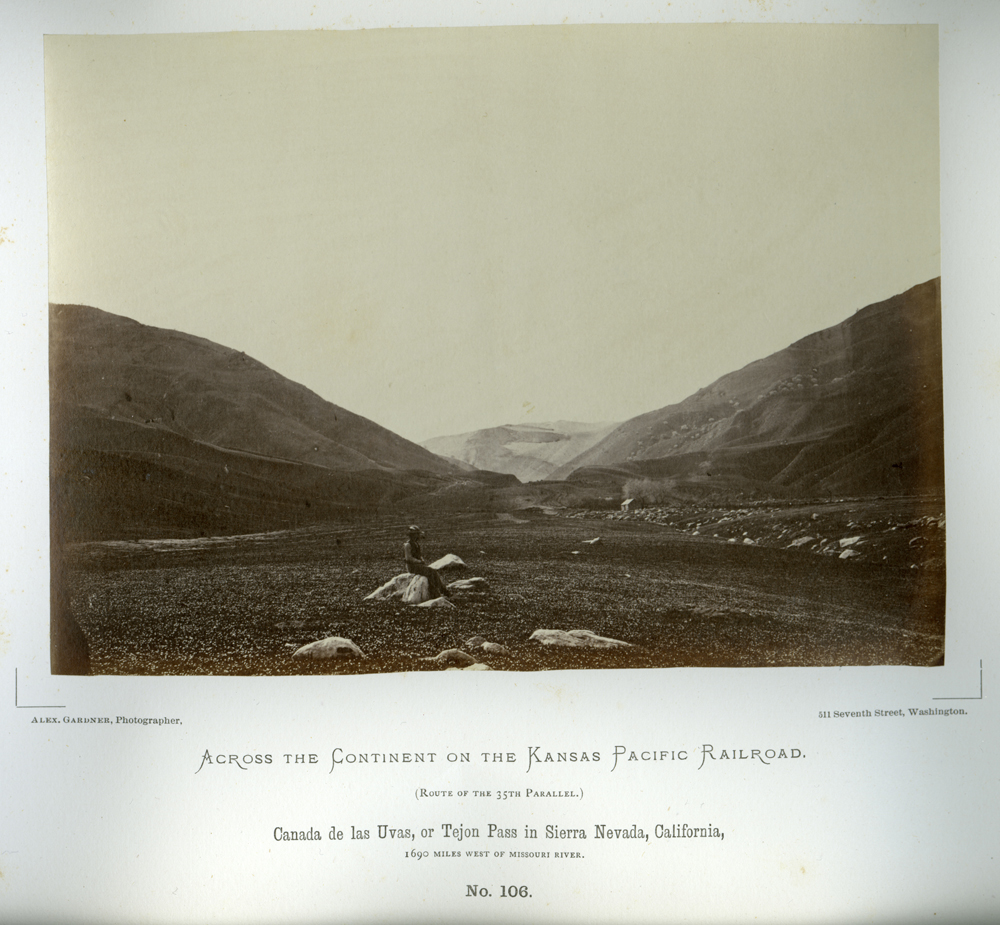

Alexander Gardner followed the construction of the Union Pacific Railroad to continue along a southwest track through Colorado, New Mexico and Arizona to the Sierra Nevada.

Raiway and photography embodied the same spirit of XIXth century progress. They were a conseguenze and a symbol of it. The be one of the first heading west and to pose for the photographer were two ways to be feel modern and be part of that incredible human Progress.

Surveys

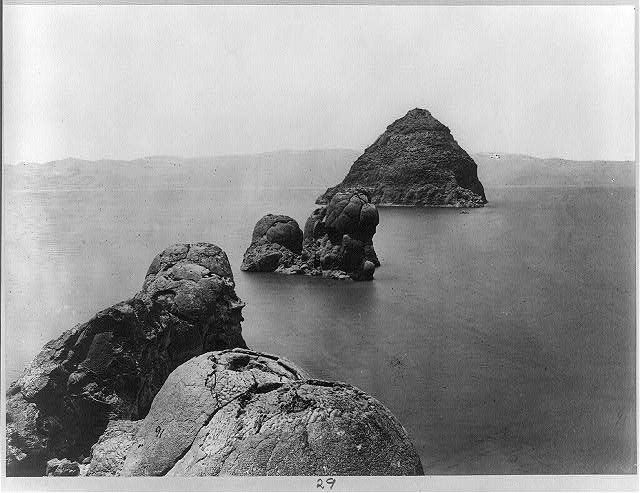

Spedizione di Clarence King al 40° parallelo.

Spedizione di Clarence King al 40° parallelo.

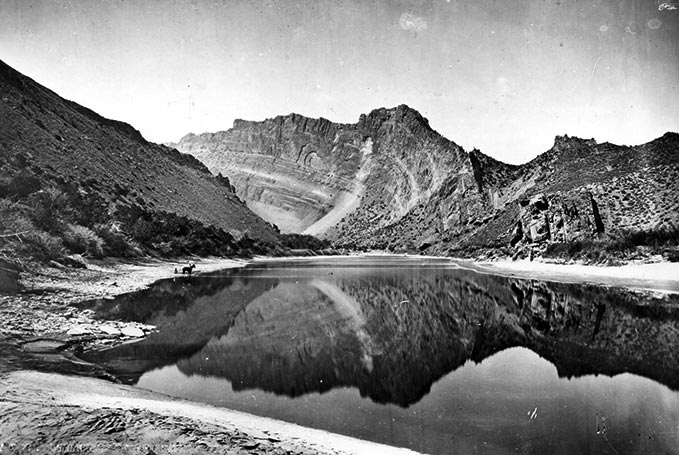

George Wheeler’s expedition west of the 100° meridian.

Geoplogical and geographical survey in Arizona 1873

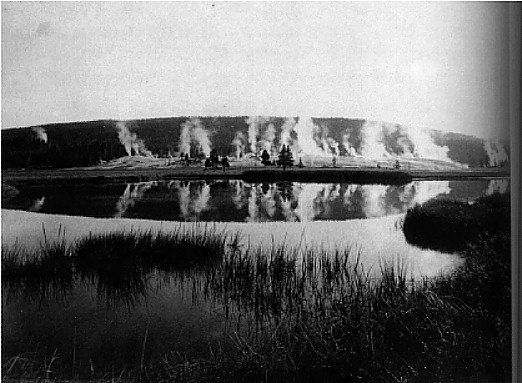

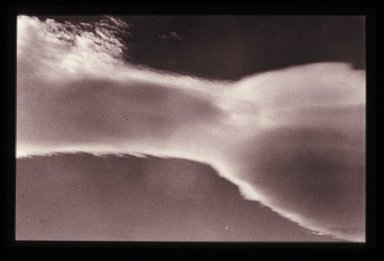

the beehive group of geysers, Yellowstone Park, 1872 Hayden Geological and Geographical expedition

Summit of Yupiter Terraces, 1871.

Hayden Geological and Geographical expedition

Rocky Mountains

assistants

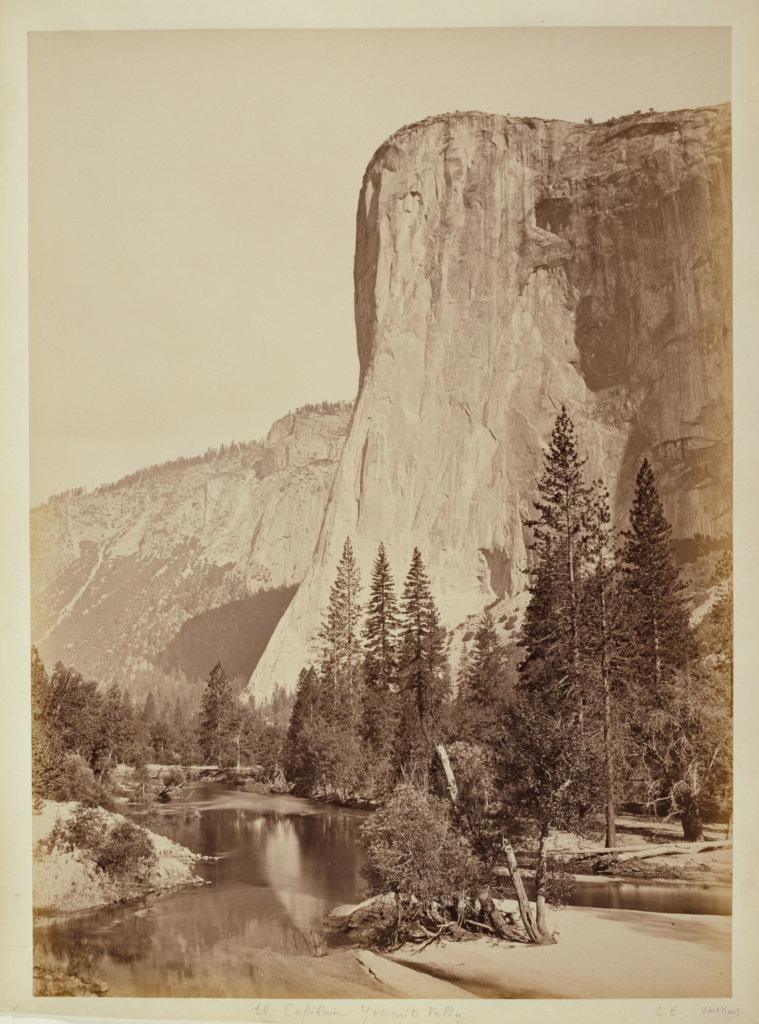

El Capitan, Yosemite, 1865

Yosemite, 1865

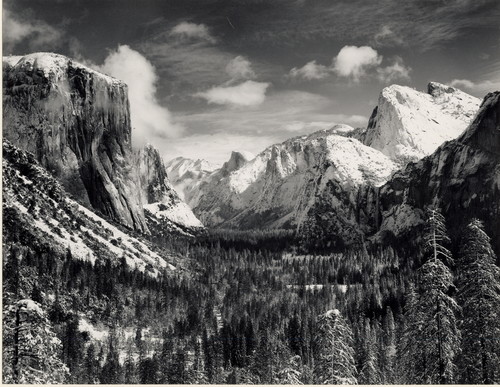

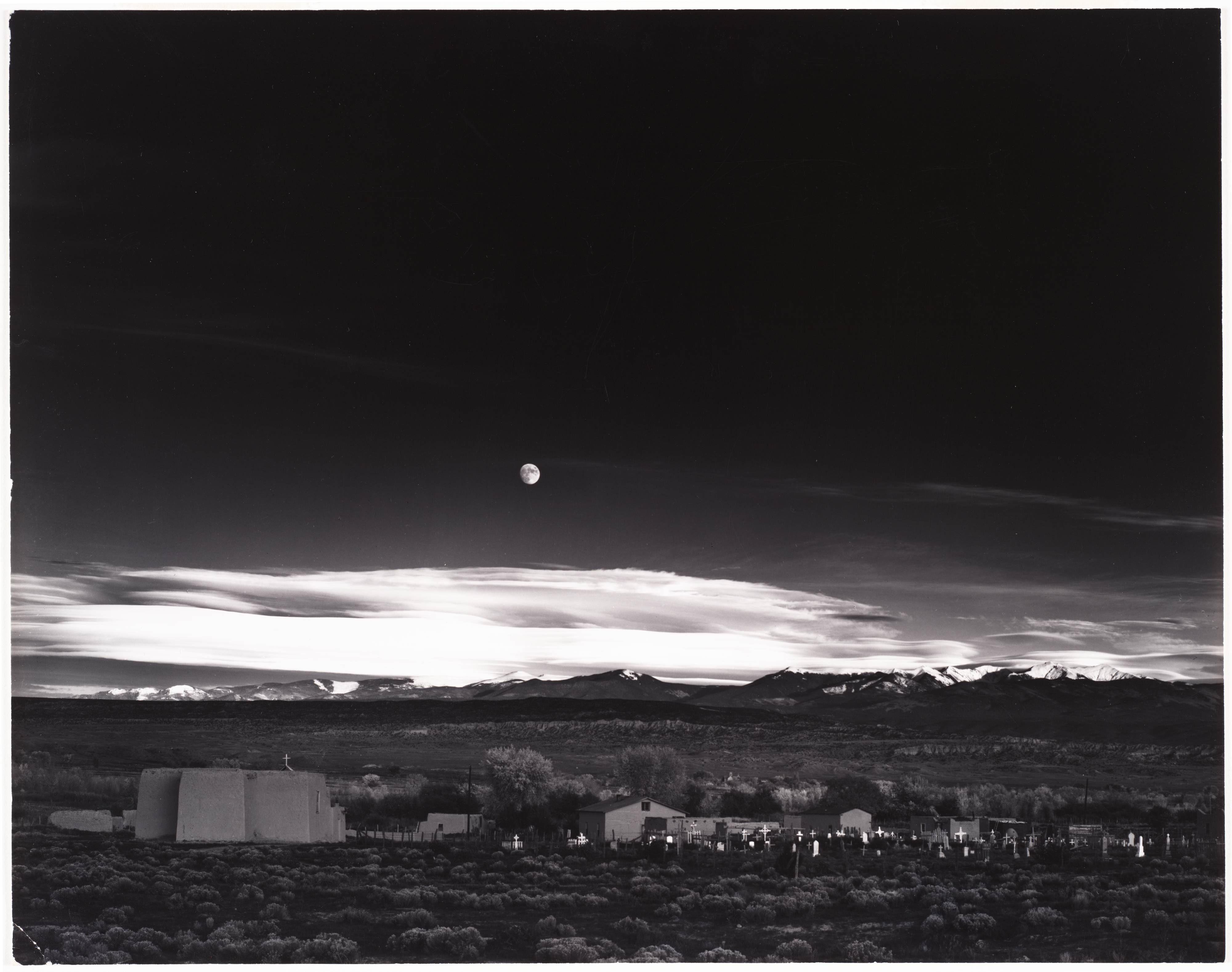

Ansel Adams (1902 – 1984)

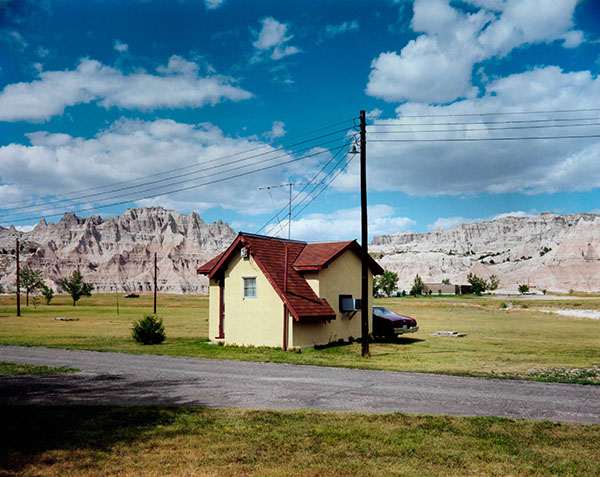

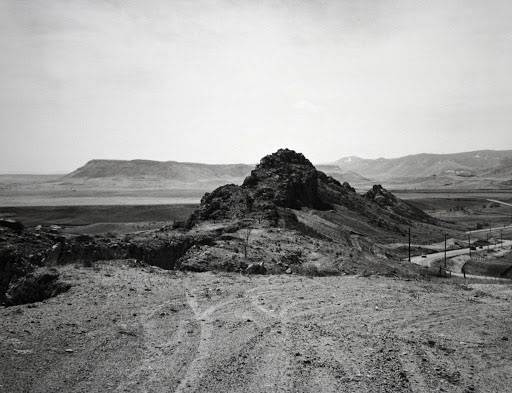

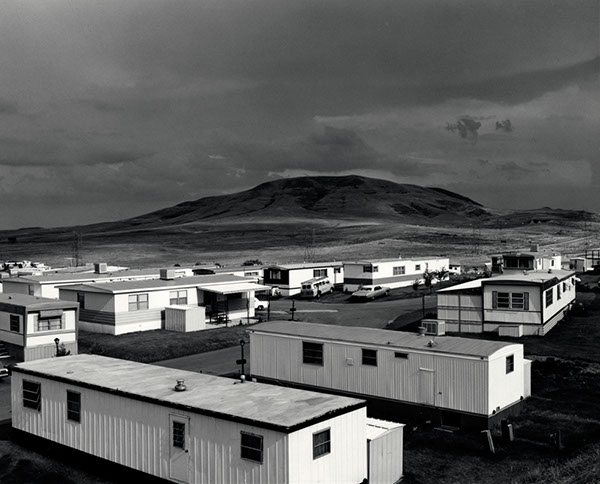

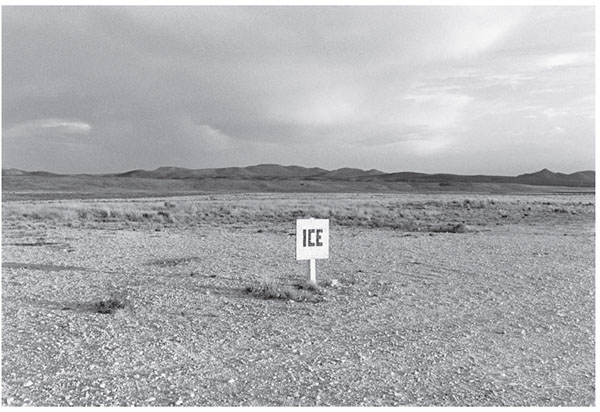

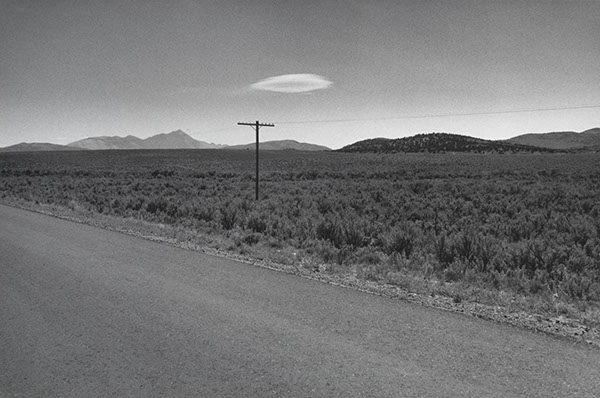

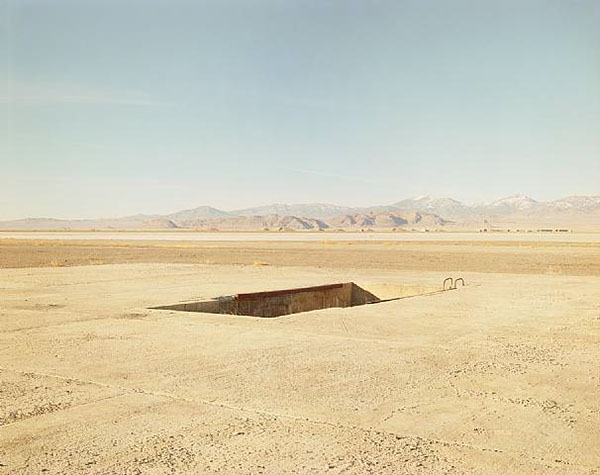

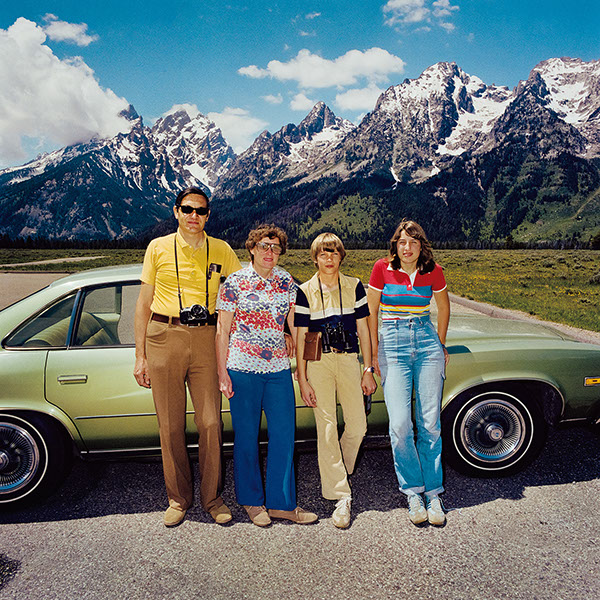

New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape

George Eastman House, Rochester, New York, 1975.

La Fontaine, al di là della critica del sistema dell’arte e della sua mercificazione, è innanzitutto una dichiarazione del potere dell’opera d’arte di rendere più elevato e più “importante” anche l’oggetto più banale e più marginale, persino l’oggetto da nascondere o di cui vergognarsi.

In questo caso la variazione di immaginario si ha per un doppio spostamento: l’oggetto è coricato sul suo dorso invece che essere in verticale e, soprattutto, uno spostamento semantico dato dalla volontà dell’artista di cambiargli contesto, inserendolo in una galleria o in una mostra o in un museo (ma è un cambio di contesto anche il fatto di diventare oggetto di una pratica artistica indipendentemente dal luogo fisico).

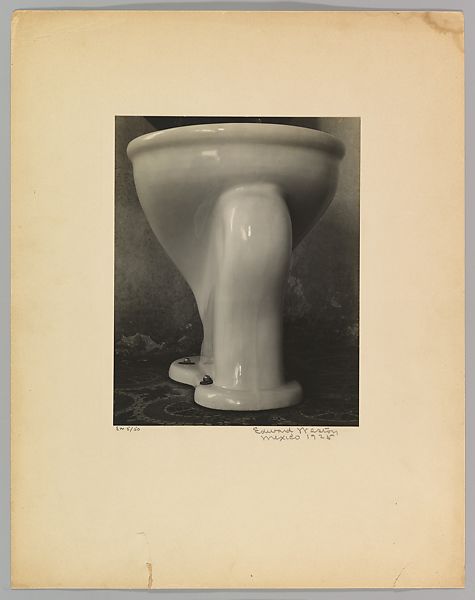

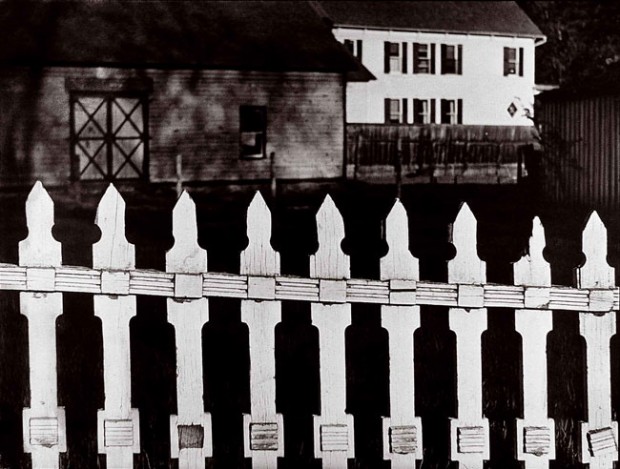

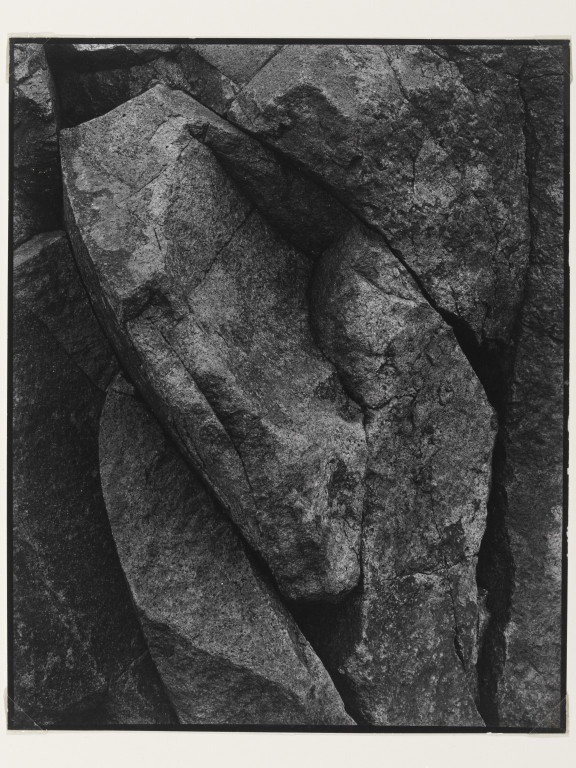

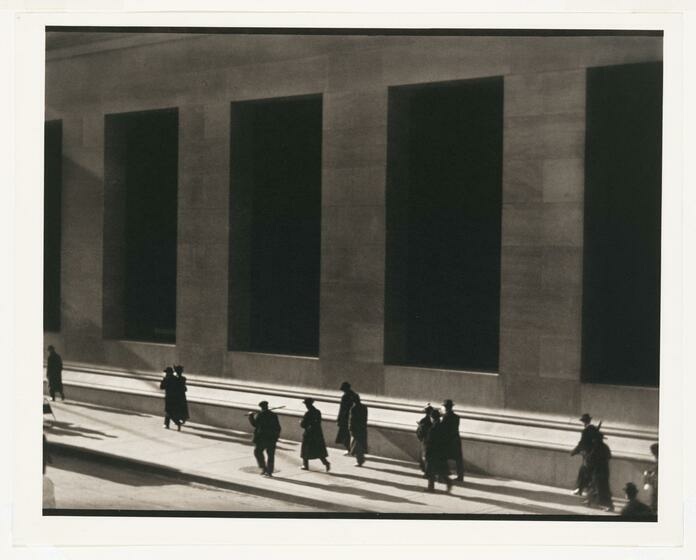

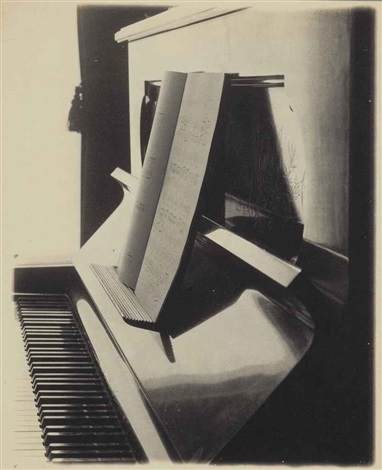

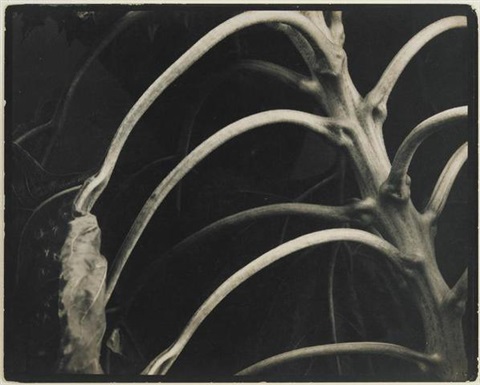

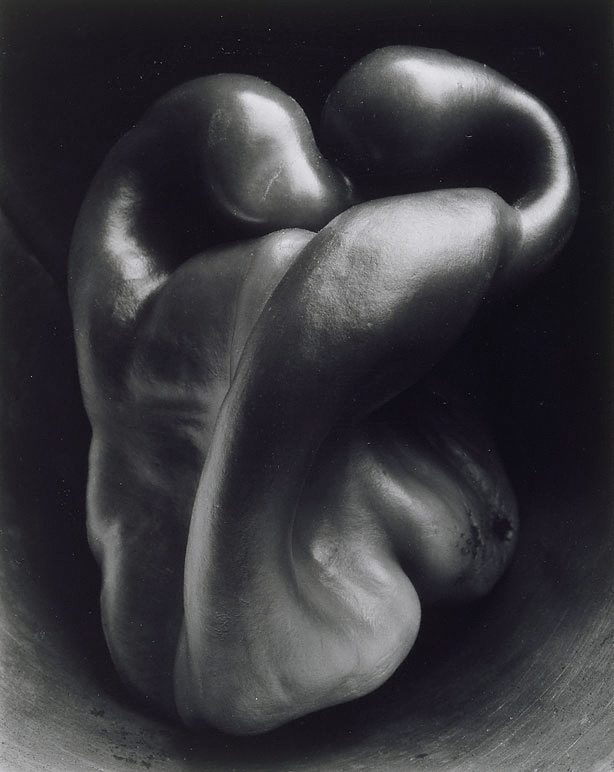

Dal punto di vista fotografico, questi anni coincidono con quelli della Straight Photography, quando una serie di autori come reazione alle pratiche pittorialiste in voga fino ad allora, cominciarono ad affermare con le loro immagini che la fotografia per essere considerata arte non aveva bisogno di assomigliare ad un dipinto o trattare di temi elevati. La fotografia tramite la potenza estetizzante dell’inquadratura, poteva rendere arte (proprio come in Duchamp) anche gli oggetti banali della vita di tutti i giorni.

Edward Weston, che di sicuro era a conoscenza del lavoro di Duchamp produce nel 1925 “Excusado”. Gli altri artisti della Straight Photography si discostano progressivamente dal pittorialismo per inquadrare direttamente e senza fronzoli le cose del mondo.

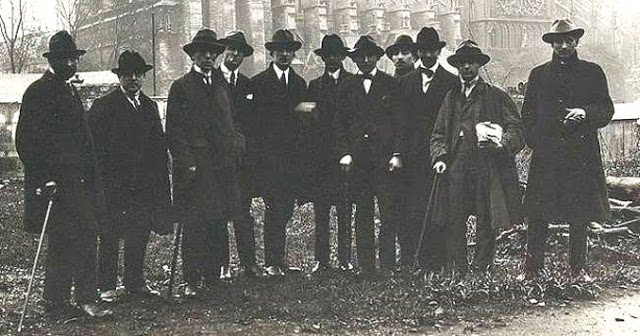

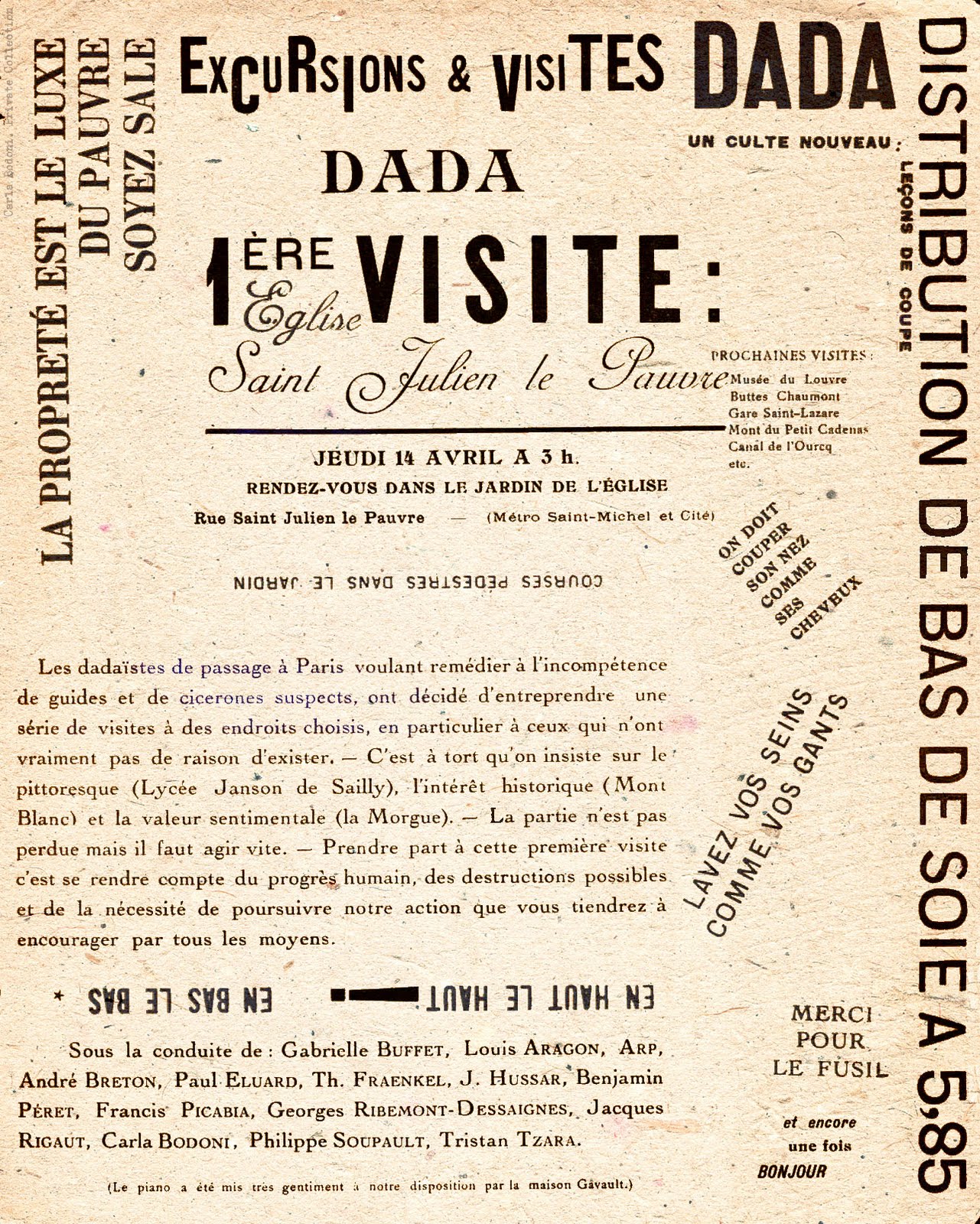

L’attenzione al banale, all’ordinario e al marginale si sposta velocemente al territorio della città: I dadaisti a Parigi nel 1921, compiono la prima di una serie di visite nelle zone urbane marginali come forma di critica alla mercificazione capitalistica dei centri urbani. Se passeggiare nella Parigi degli Champs Elysees è ormai esclusivamente una esperienza consumistica e una partecipazione al sistema di produzione capitalistico, passeggiare nei margini della città diventa un modo per riaffermare il diritto allo spazio pubblico e il diritto ad un utilizzo “inutile” e non produttivo dello stesso.

Dada opera così una “trasformazione” estetica dello spazio urbano in qualcosa da rielaborare ospitando letture, azioni improvvisate, coinvolgimento dei passanti, distribuzione di doni e di racconti.

L’unica produzione di quella azione è il volantino di invito e una fotografia di gruppo dei partecipanti:

Passando per le deambulazioni surrealiste (in cui comunque confluiscono Aragon e Breton fra gli altri), la pratica dell’attraversamento dello spazio banale si continua a sviluppare come forma di riappropriazione dello spazio e di critica della cessione dello spazio pubblico al sistema produttivo capitalistico.

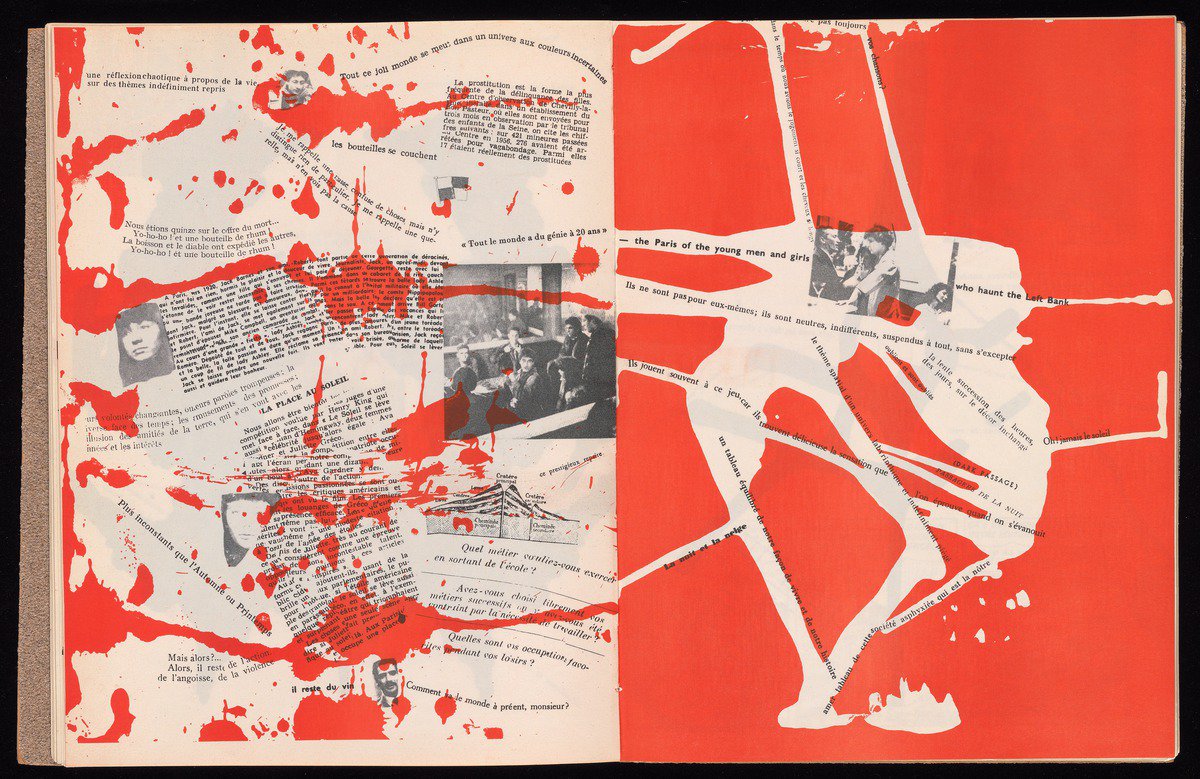

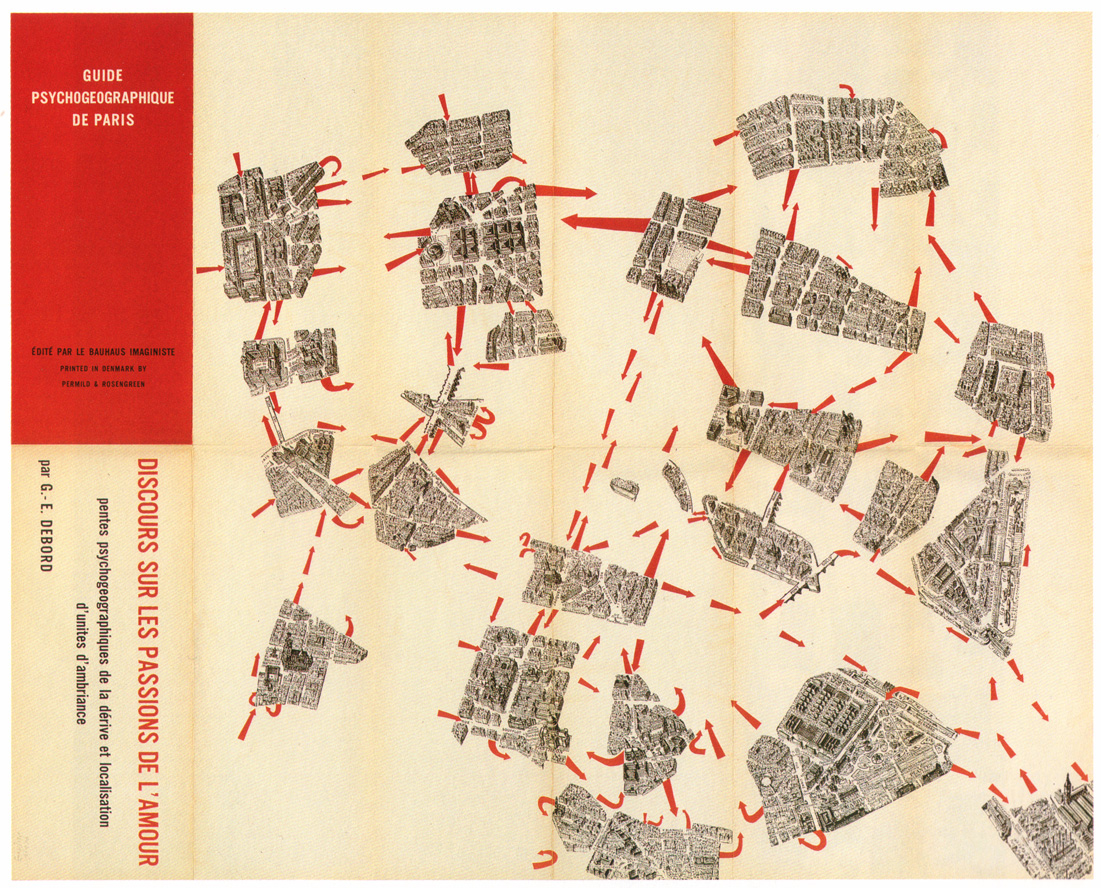

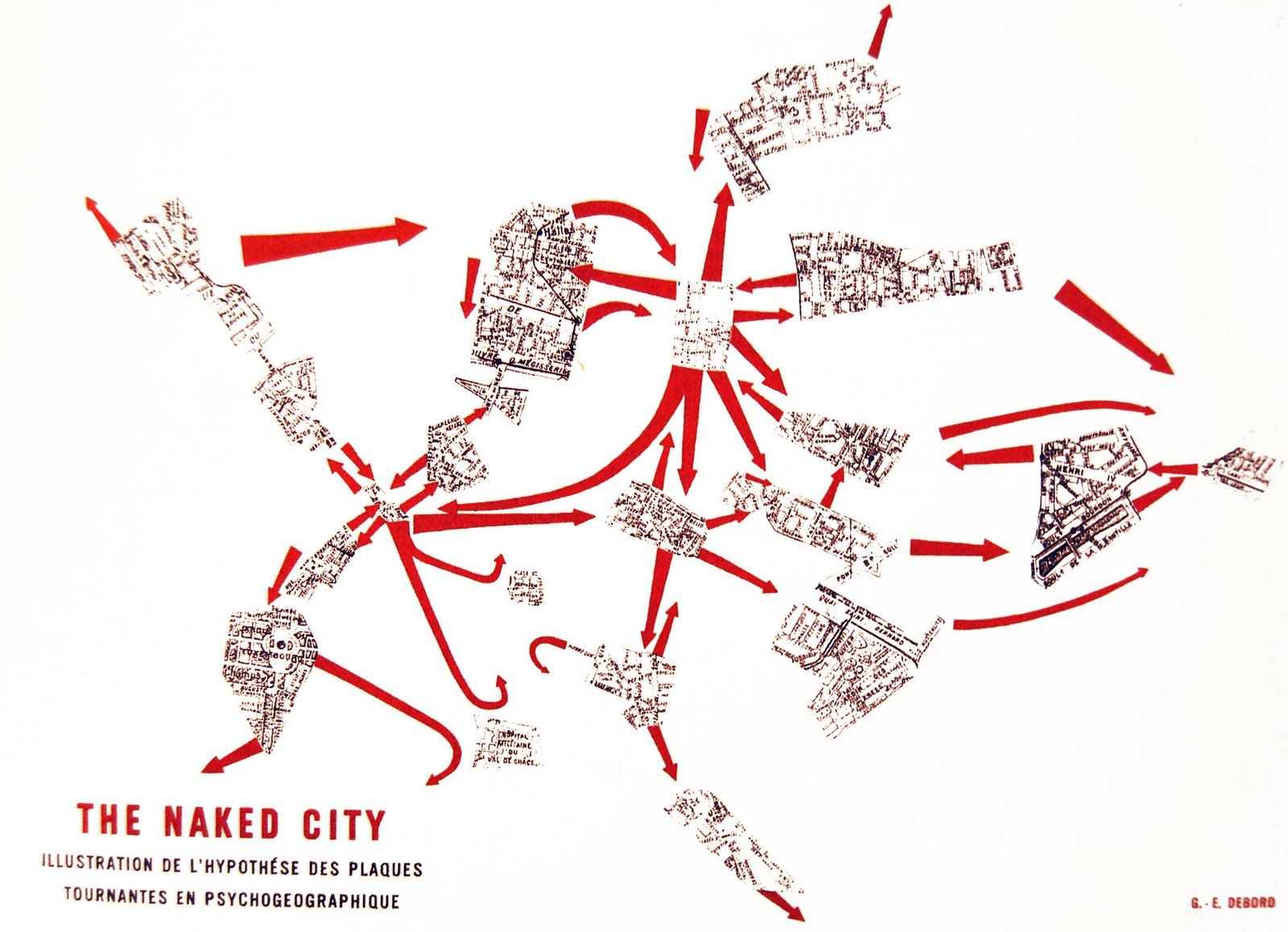

Nel 1952 un gruppo di giovani scrittori – Guy Debord, Gil, Wolman, Michèle Bernstein, Mohamed Dahou, Jacques Fillon e Gilles Ivain – diede vita all’Internazionale Lettrista per lavorare alla costruzione cosciente e collettiva di una nuova civiltà. Nei primi anni Cinquanta, quest’ultima – che confluì nel 1957 nell’Internazionale Situazionista – riconobbe nel perdersi in città la concreta possibilità espressiva dell’anti-arte e la assunse come mezzo estetico-politico per sovvertire il sistema capitalista del dopoguerra. Dopo la visita dadaista e la deambulazione surrealista, venne coniato il termine dérive: un’attività ludica collettiva che mirava alla costruzione e alla sperimentazione di nuovi comportamenti nell’esistenza reale; un modo alternativo di abitare la città, uno stile di vita che andava fuori e contro le regole della società borghese e che voleva con ogni mezzo superare le correnti precedenti. Per la deriva lettrista lo spazio urbano era un terreno passionale oggettivo e non solo soggettivo-inconscio. Non si trattava più di una fuga dal reale, bensì di un concreto controllo dei mezzi e delle azioni che si possono sperimentare direttamente nella città.

Un concetto di città nuova, abitata e costantemente “errata” da un uomo che la usa unicamente come playground e come spazio di flanerie e di deriva, viene sognato e progettato dai situazionisti.

L’atteggiamento ludico è considerato l’unico in grado di mettere sotto scacco le logiche di produzione e di marginalizzazione.

Il gioco diviene oggetto privilegiato della speculazione architettonica anche della progettazione concreta: L’architetto Aldo Van Eyck individua nel playground un nuovo modo di appropriazione dello spazio urbano e progetta le prime aree giochi ad Amsterdam (1947-1978).

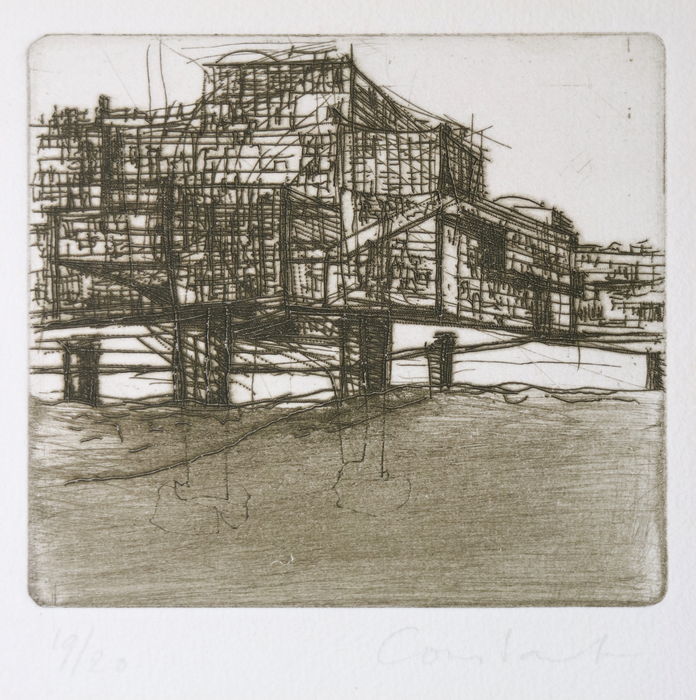

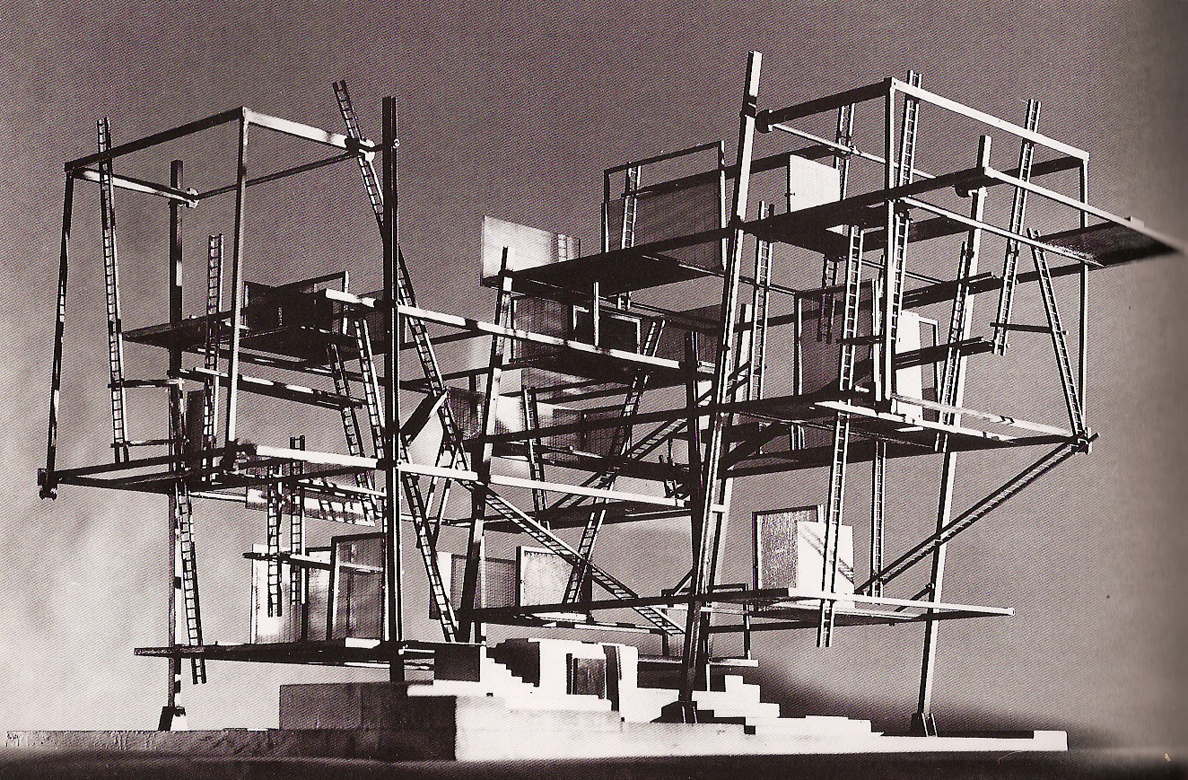

Constant, grazie anche all’aiuto di Van Eyck, propone la New Babylon, una città futura anticapitalista, nella quale l’homo faber è sostituito dal nuovo homo ludens (Johan Huizinga, 1938). Nella New Babylon il valore simbolico del gioco si carica di significato nella polemica contro il moderno; alla città funzionalista, meccanizzata si contrapporre una città che recupera il suo rapporto con la strada e con gli spazi pubblici informali.

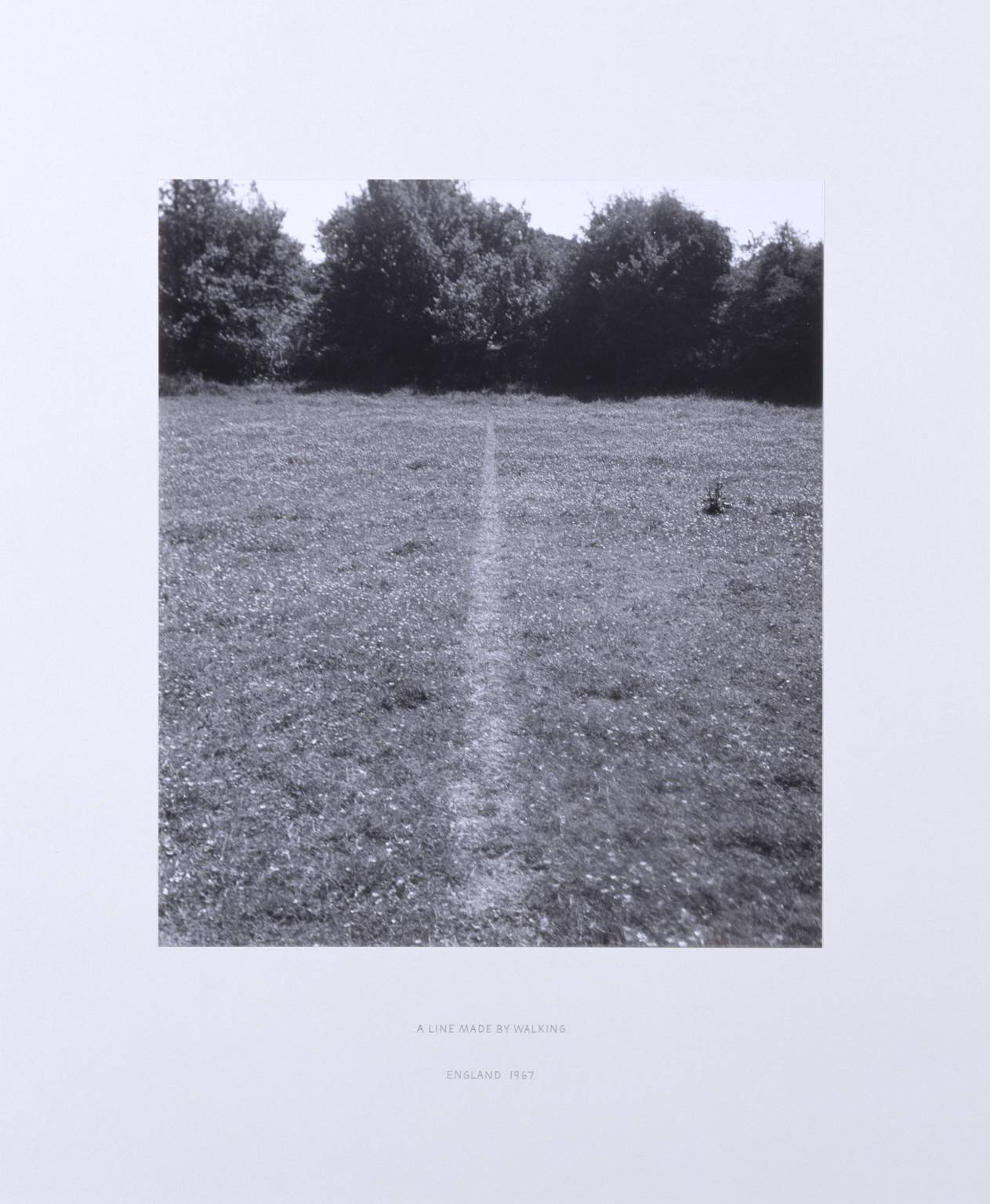

Alla chiusura dell’esperienza situazionista nel 1978 una nuova generazione di artisti americani analizza le potenzialità della pratica artistica e dell’opera d’arte come strumento di rimodifica e riconfigurazione del paesaggio: NASCE LA LAND-ART.

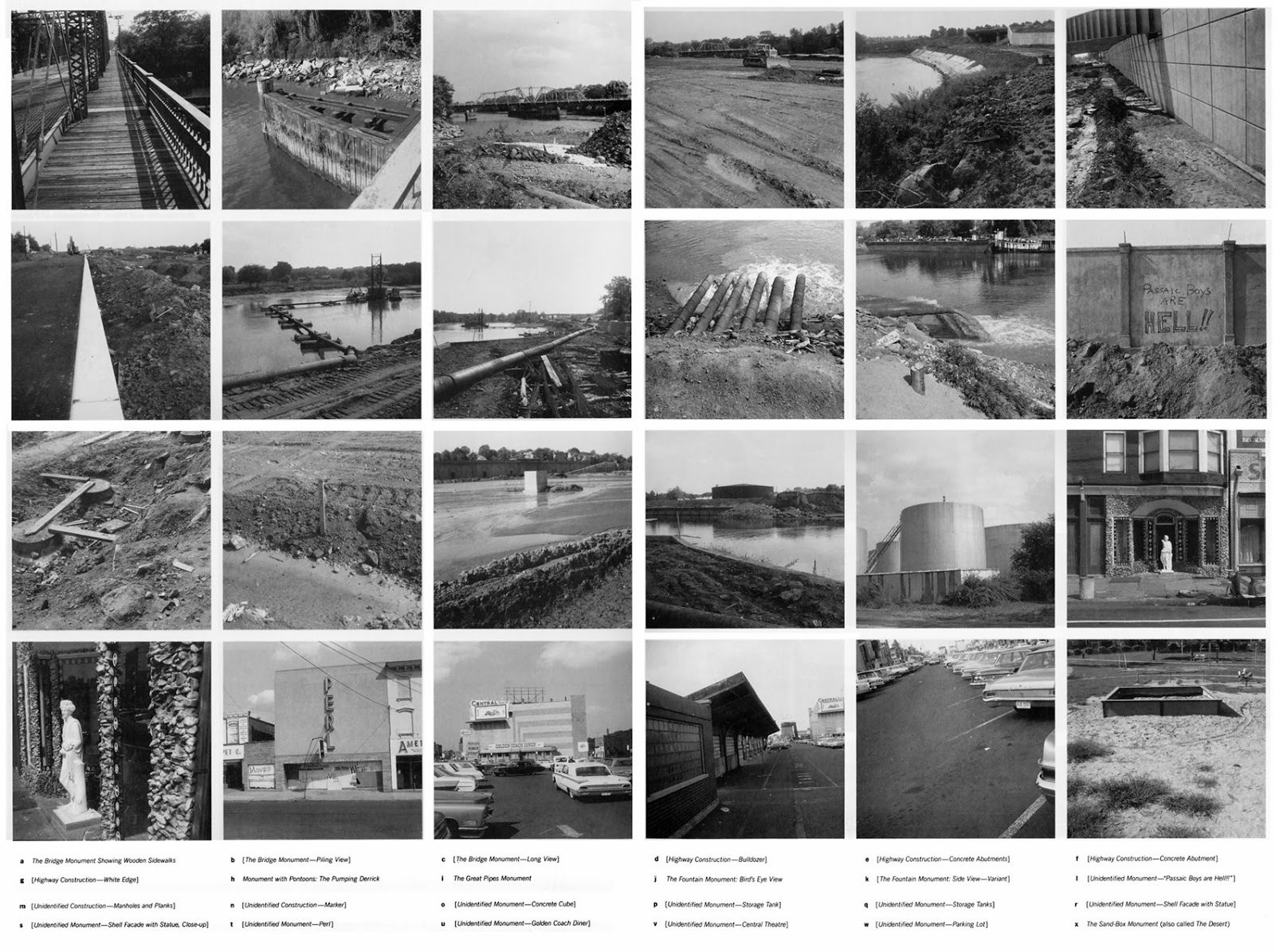

Nel 1967 Roberth Smithson compie un attraversamento fra New York e il paese di Passaic nel New Jersey, dove era cresciuto, e produce un breve saggio testuale e visivo in cui descrive le varie reliquie industriali e suburbane che incontra durante il viaggio, riconfigurandole in ipotetici monumenti di una civiltà a venire. Pur non essendo fra le sue opere più conosciute, “A tour of the monuments of Passaic, New Jersey” ci da un esempio chiarissimo della funzione di riconfigurazione di un immaginario di un dato paesaggio che può avere la pratica artistica.

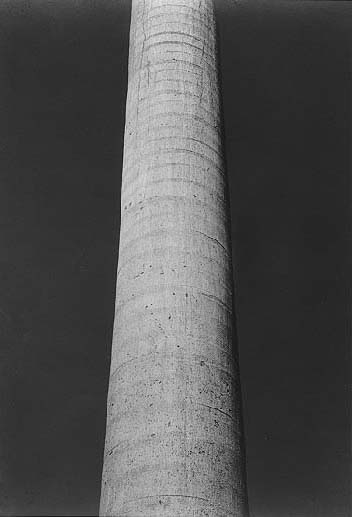

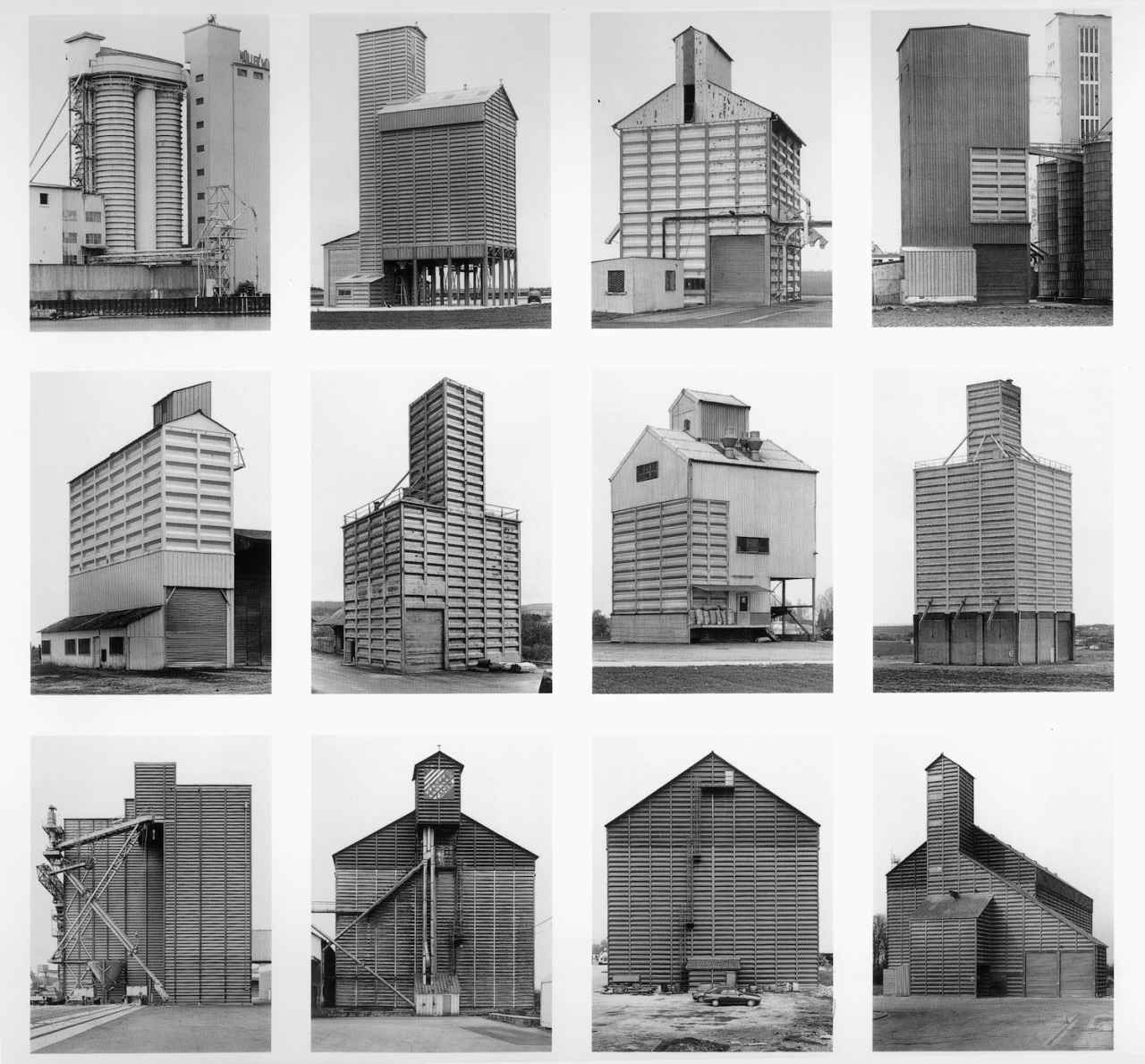

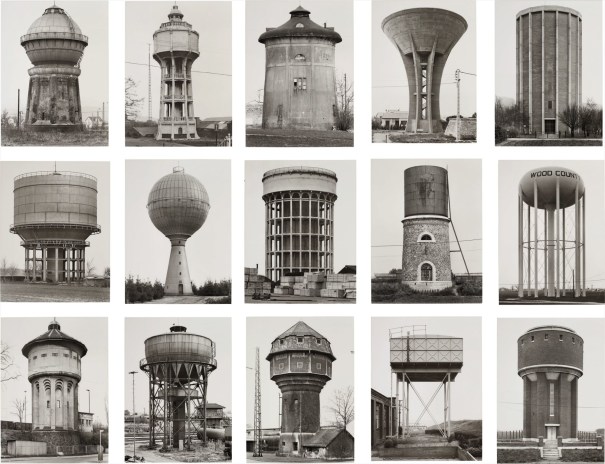

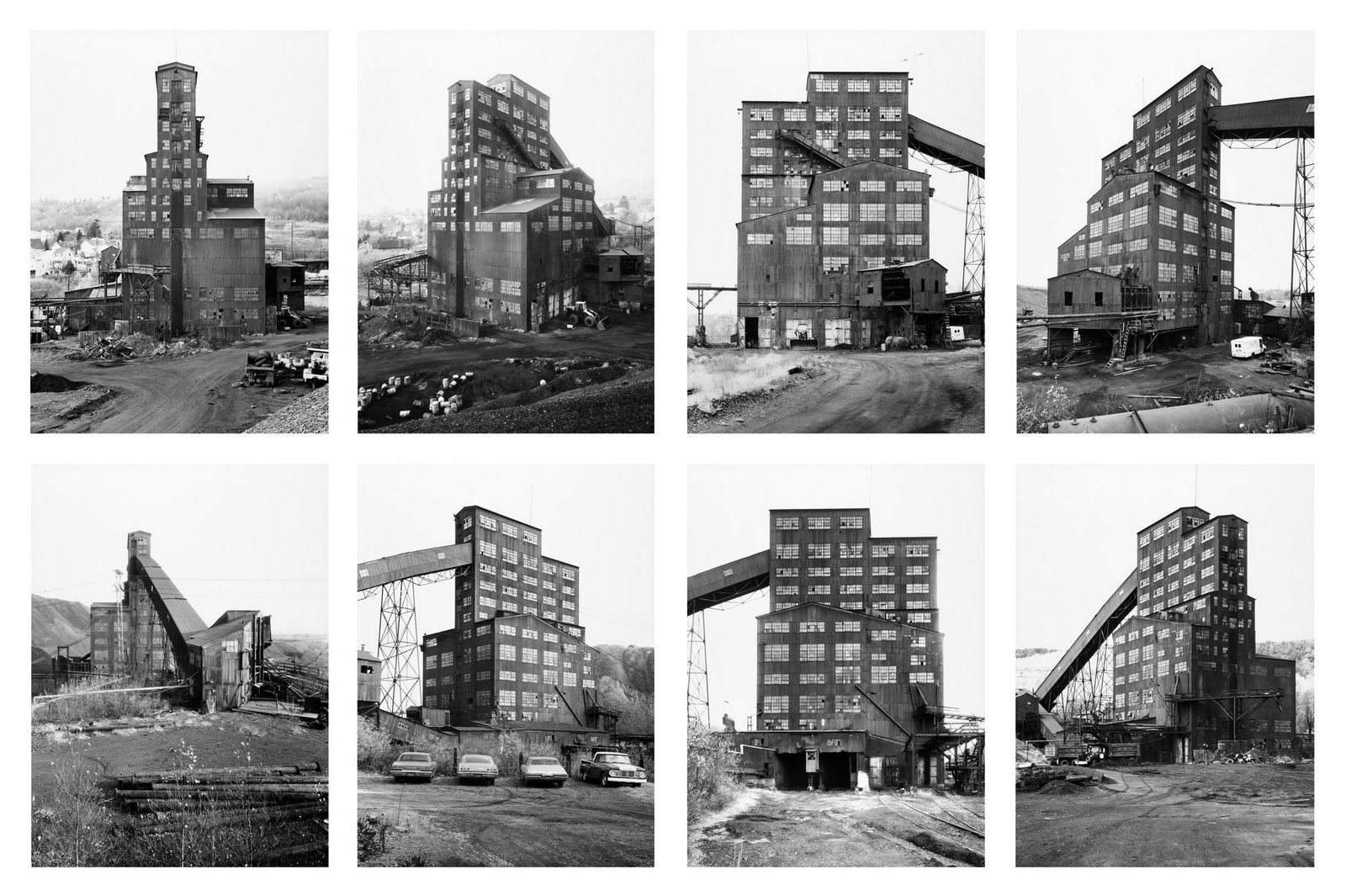

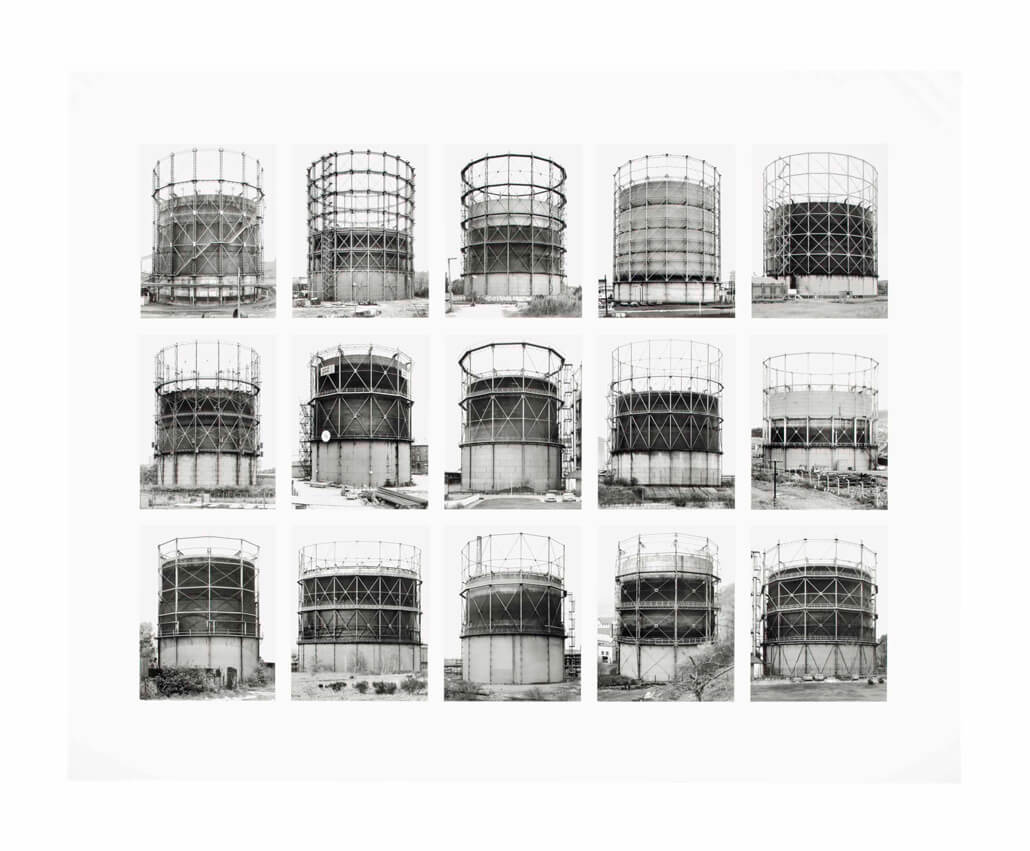

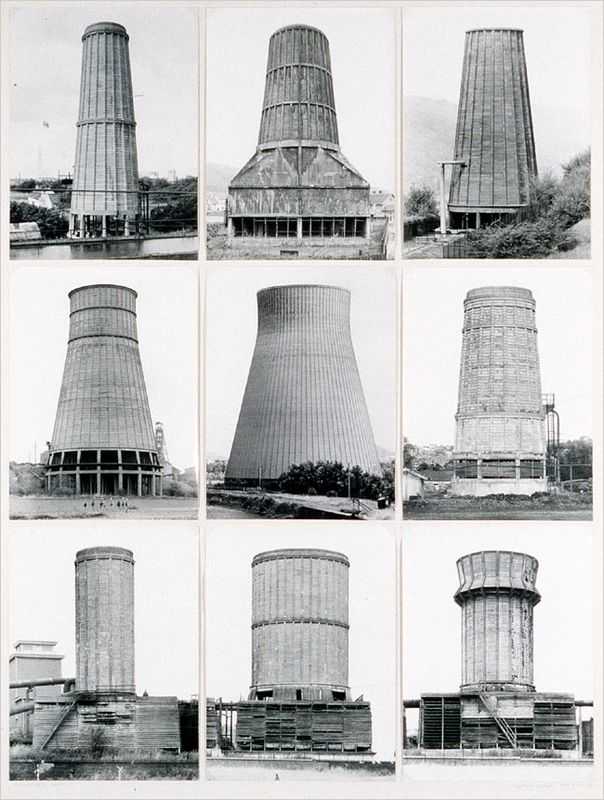

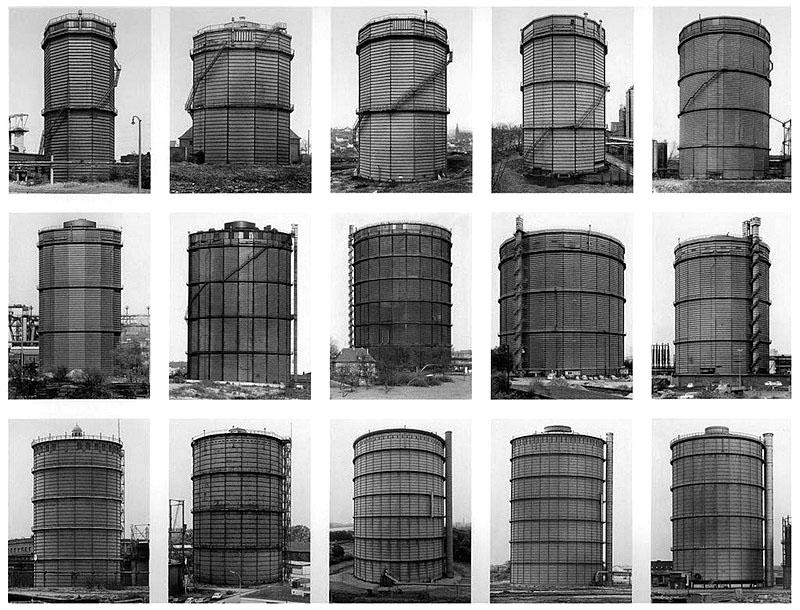

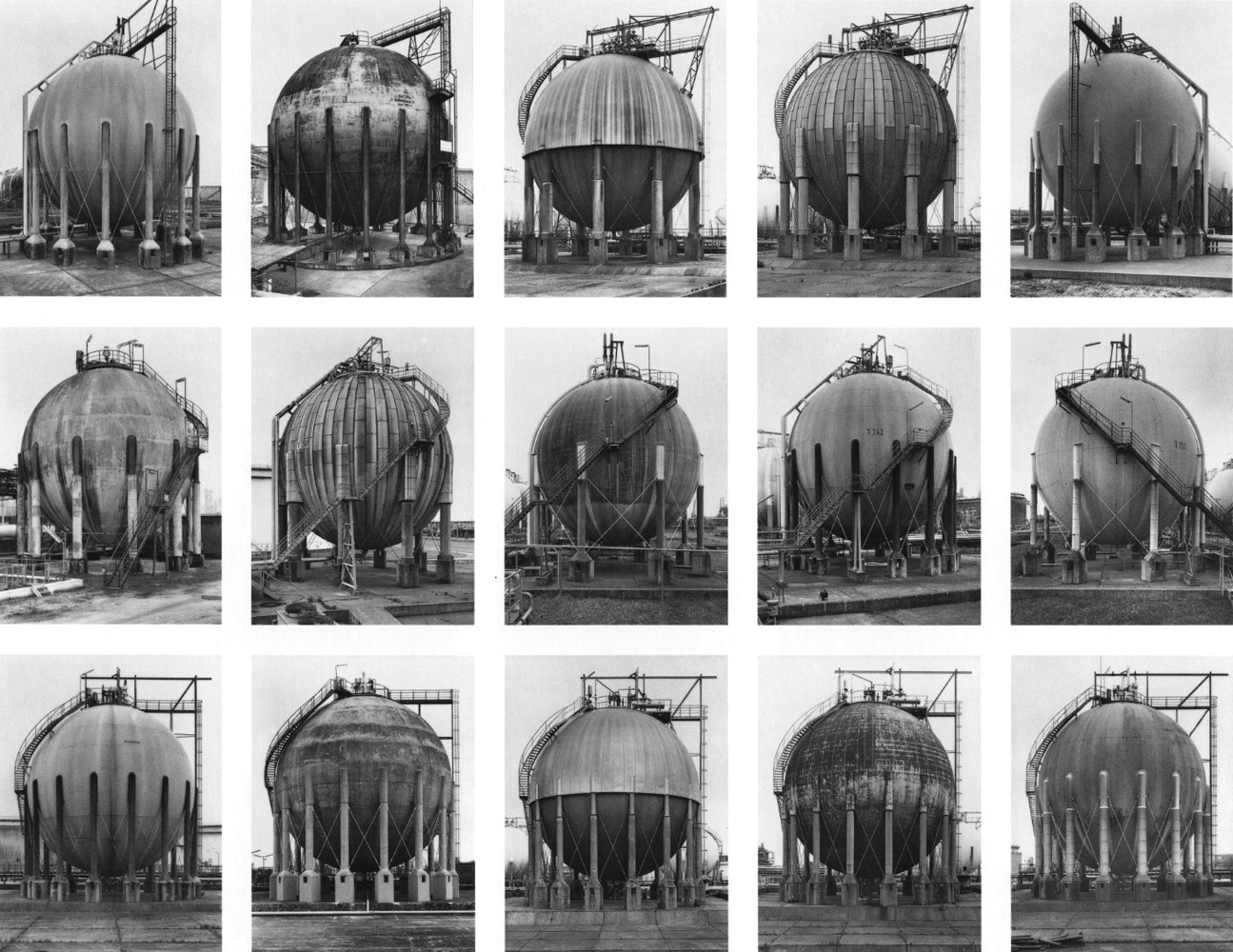

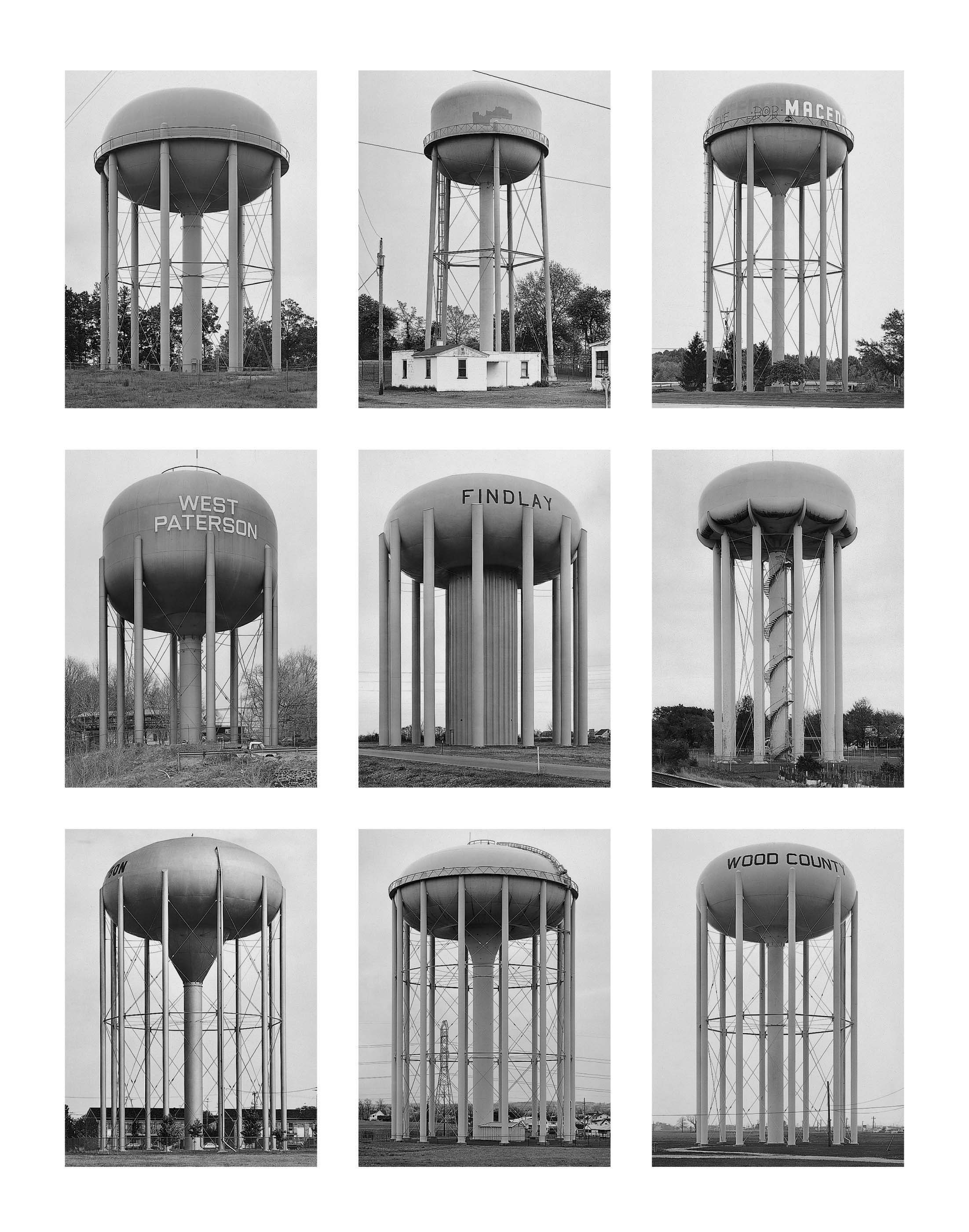

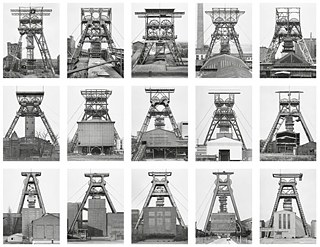

L’effetto di monumentalizzazione che il mezzo fotografico ha sul suo soggetto è anche chiara nell’imponente lavoro di Berndt e Hilla Becher “Anonyme Skulpture: Eine Typologie technischer Bauten” edita nel 1970.

Pur essendo un lavoro eminentemente fotografico il termine Skulpture è significativo e in effetti nel 1990 i Becher vinsero il Leone D’Oro alla Biennale di Venezia proprio nella categoria Scultura. La catalogazione rende visibilissimo lo spostamento di senso che il mezzo fotografico opera su queste emergenze industriali trasformandole appunto in sculture con un meccanismo simile a quello del primo ready-made di Duchamp. Solo che qui lo spostamento semantico non è operato fisicamente (ad esempio spostando uno di questi silos in un museo) ma a livello di immaginario attraverso l’inquadratura (che in effetti rende “portatili” questi soggetti).

Inoltre l’atteggiamento degli autori di fronte a questi “monumenti” È cambiato in senso post-modernista. Non sono più simboli della grande narrativa del progresso umano davanti a cui inchinarsi, ma reperti – come in un teca di un museo – di un passato glorioso e fallito. Mettendole nella teca fotografica le musealizzano, come è successo alle vestigia di altri imperi.

Nello stesso periodo Alain Touraine (La societé post-industrielle, 1969) e Daniel Bell (The Coming of Post-Industrial Society, 1973) utilizzano per la prima volta il termine “post-industriale” che in economia è utilizzato per indicare una società in cui la il lavoro per la produzione di servizi ha superato come quantità di lavoratori e di indotto economico quello della manifattura di beni; ma a livello sociale, urbanistico e culturale significa che gli stessi edifici industriali cominciano a perdere la loro funzione e diventano archeologia (industriale) o sono convertiti in istituzioni culturali in corrispondenza con la nascita dell’ “industria culturale”.

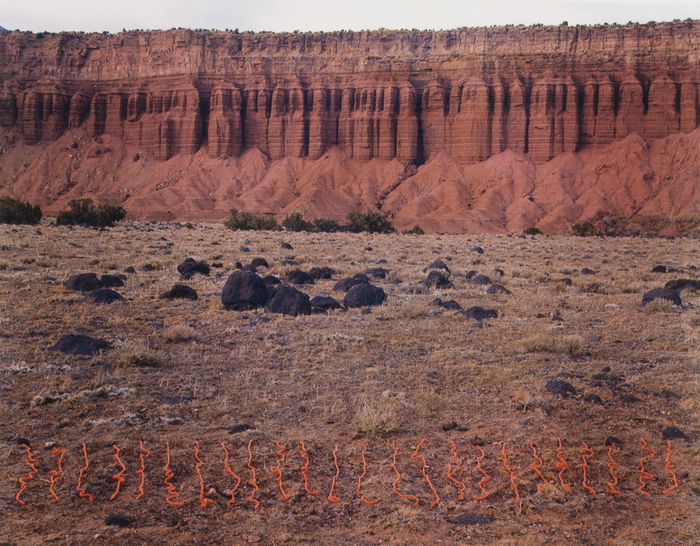

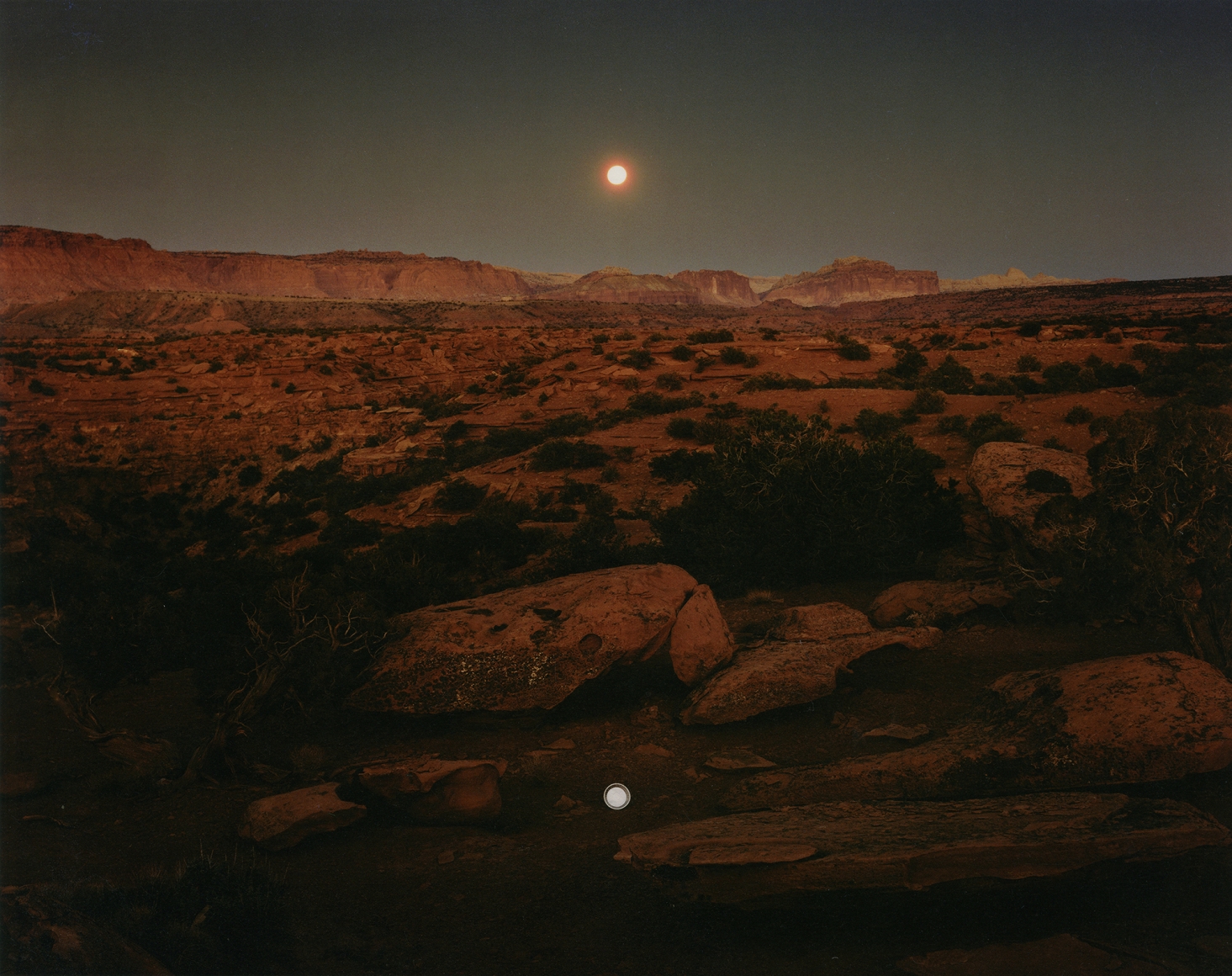

Su questo solco, poco più tardi, si inserisce la serie Altered Landscape di John Pfahl (1974-78):

Wednesday july 27th

Fori Imperiali

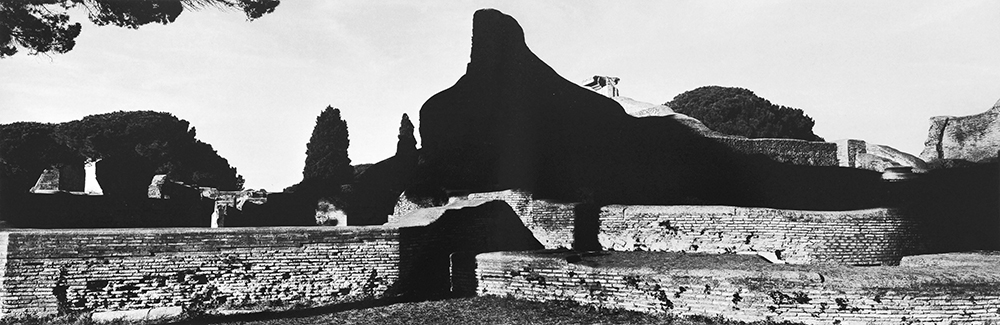

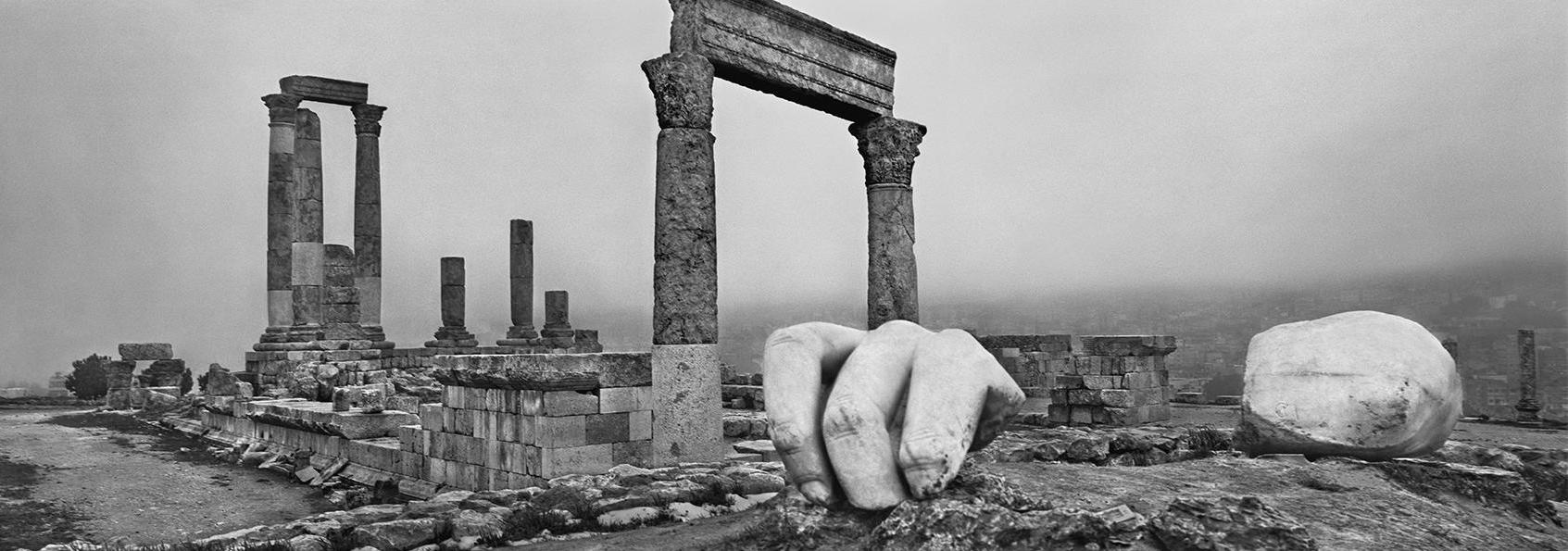

Very close to very far: Josef Koudlka and Fori Imperiali romans ruins

THURSDAY july 28th

Roma center, Pantheon, Navona, Piazza del Popolo.

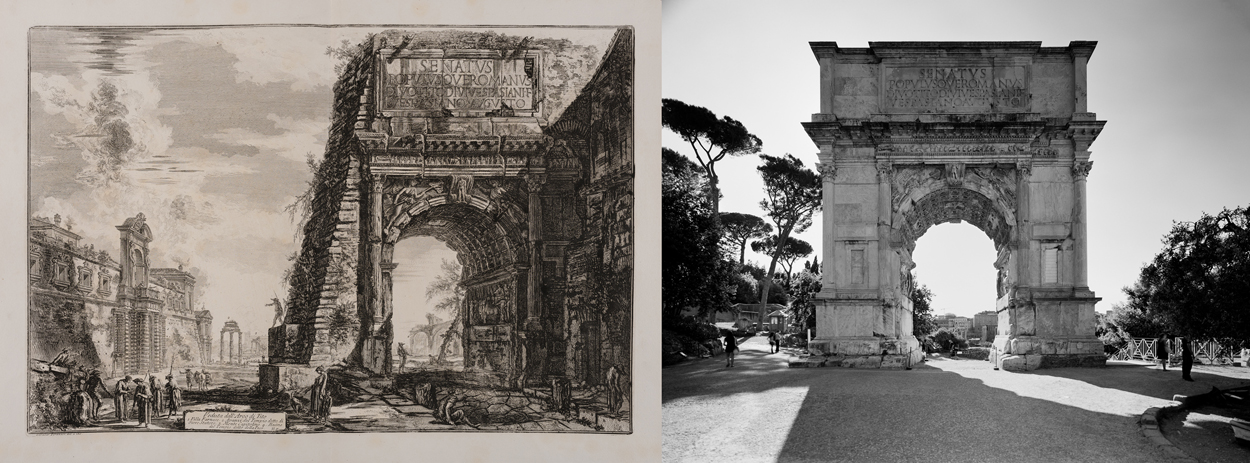

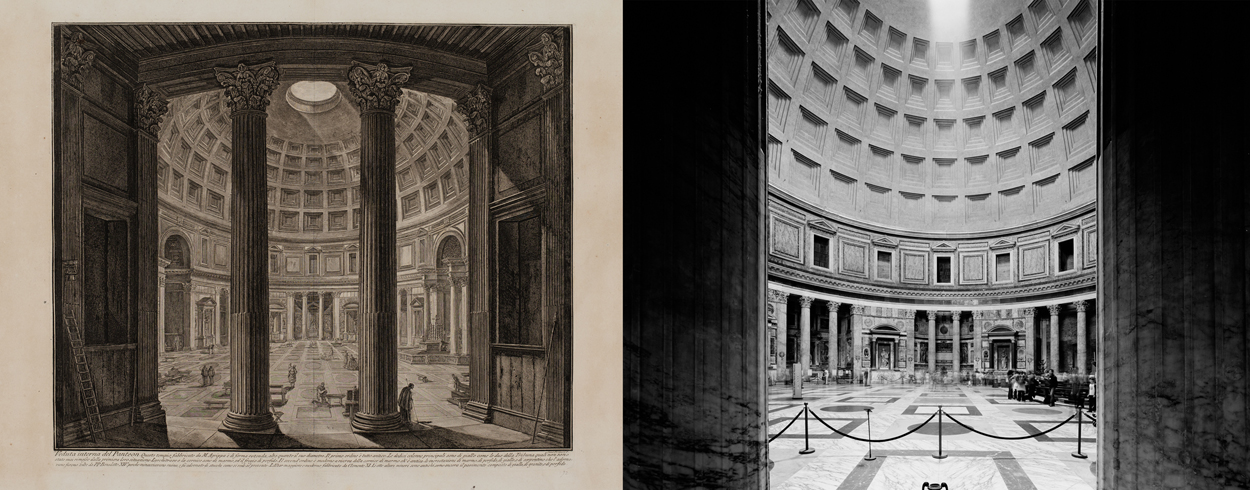

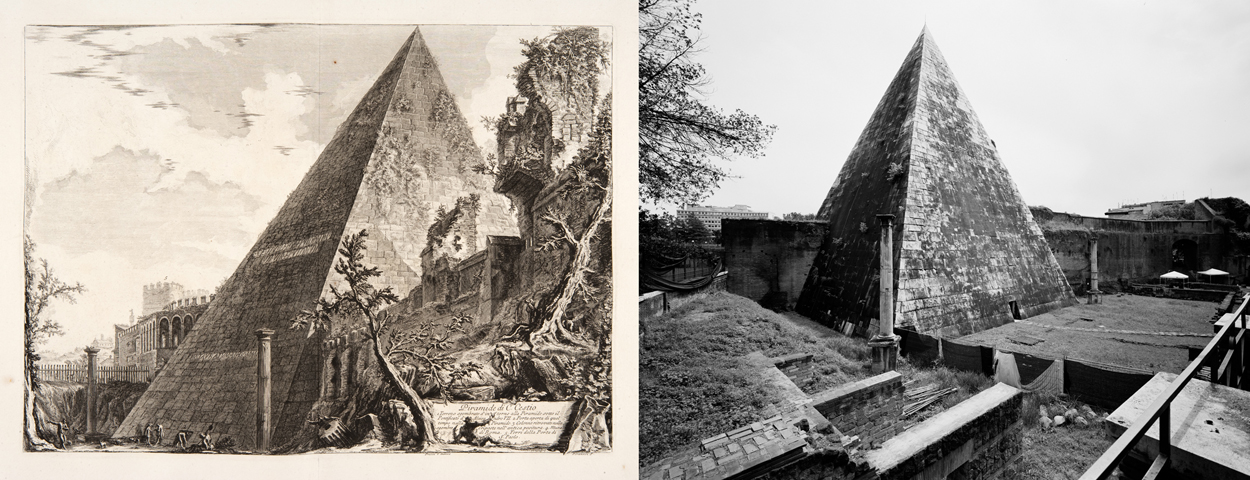

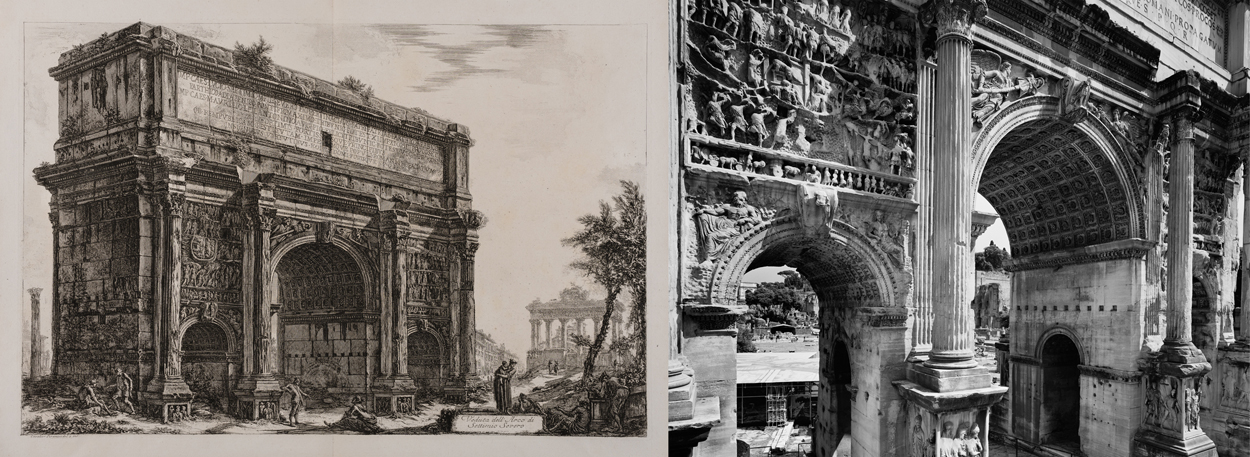

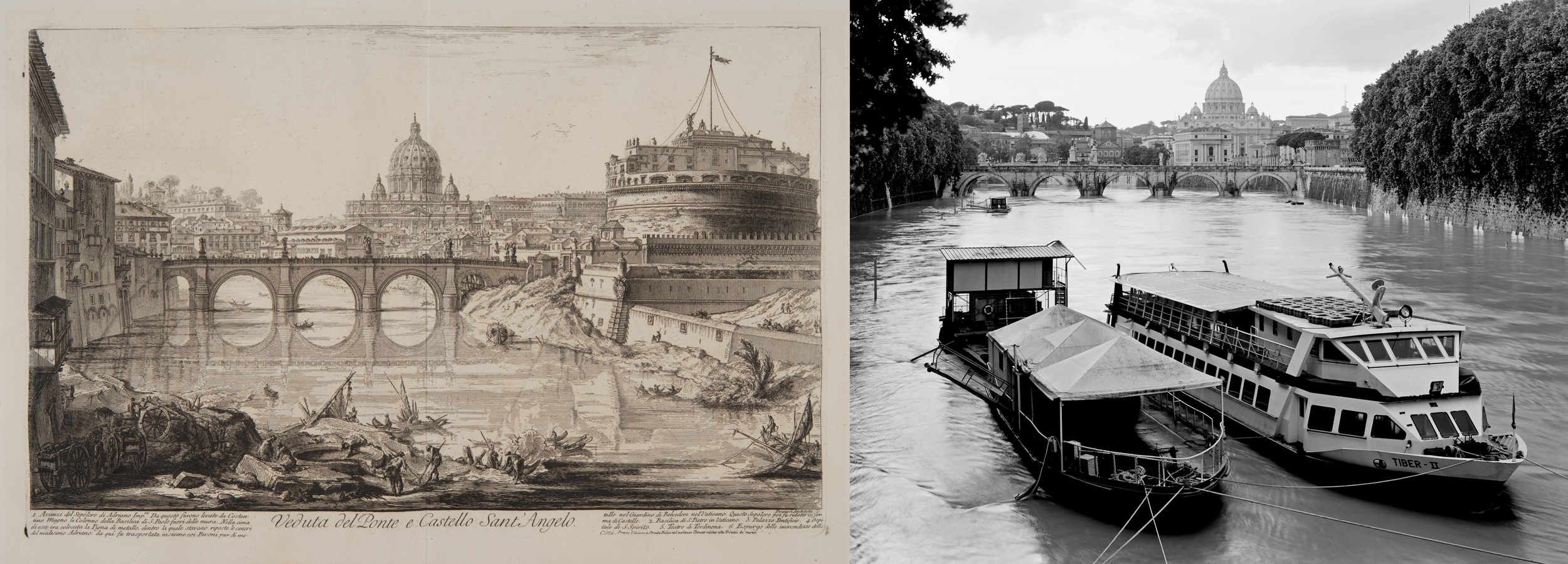

Monumentality: Gabriele Basilico and Piranesi grand views of Rome

monuments.

FRIday july 29th

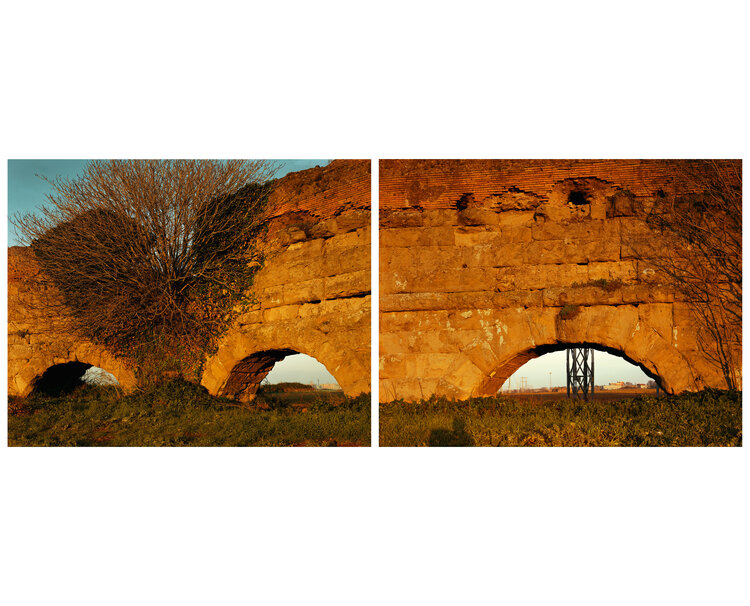

Acquedotto Claudio, Via del Mandrione, Casilina Vecchia.

Following the water: Hans Cristian Schink and the Ancient Roman Aqueduct of Acqua Claudia.

MONDAY AUGUST 1ST

Cinecittà

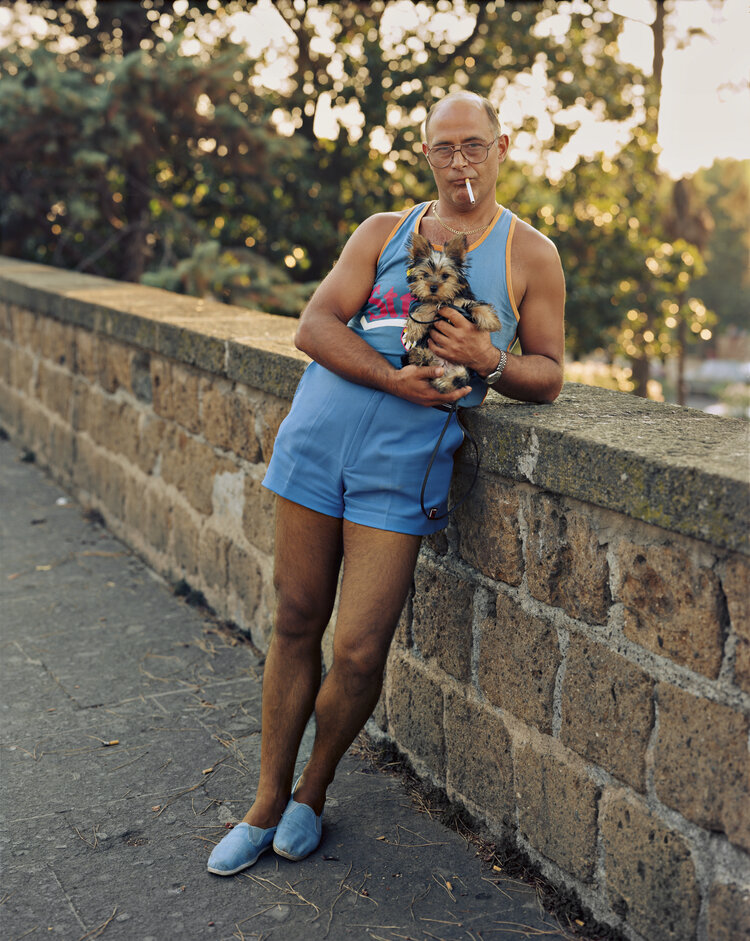

Dolce Vita decadence: Gregory

Crewdson eye on Cinecittà

TUESDAY AUGUST 2ND

Location: Appia Antica and Caffarella.

Stratification and urban gradient: Joel Sternfeldt and Campagna Romana

WEDNESDAY AUGUST 3RD

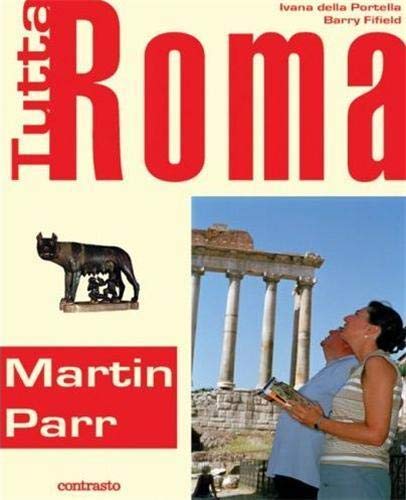

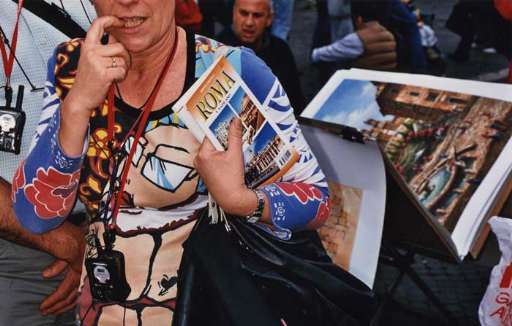

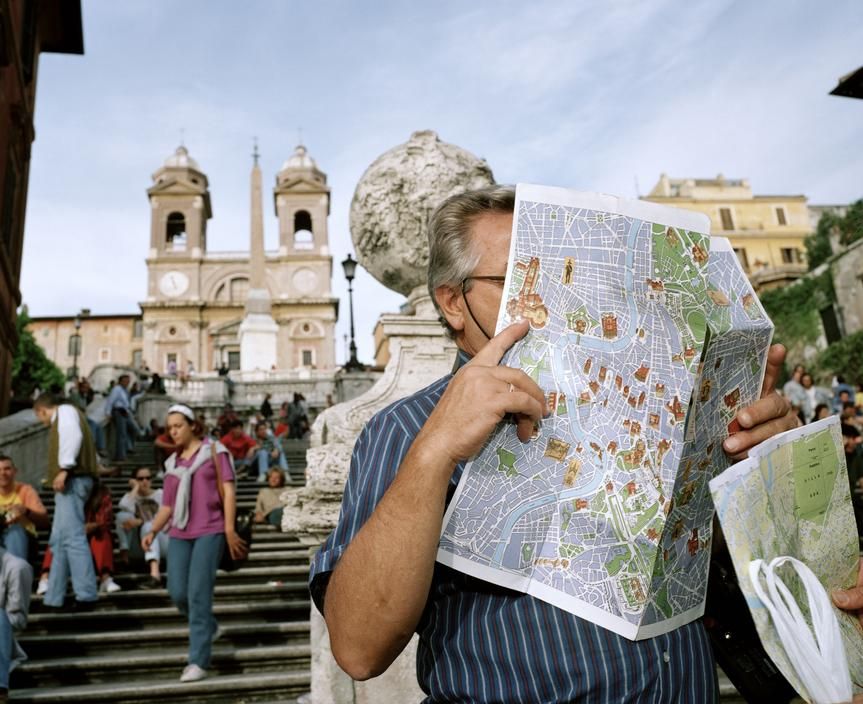

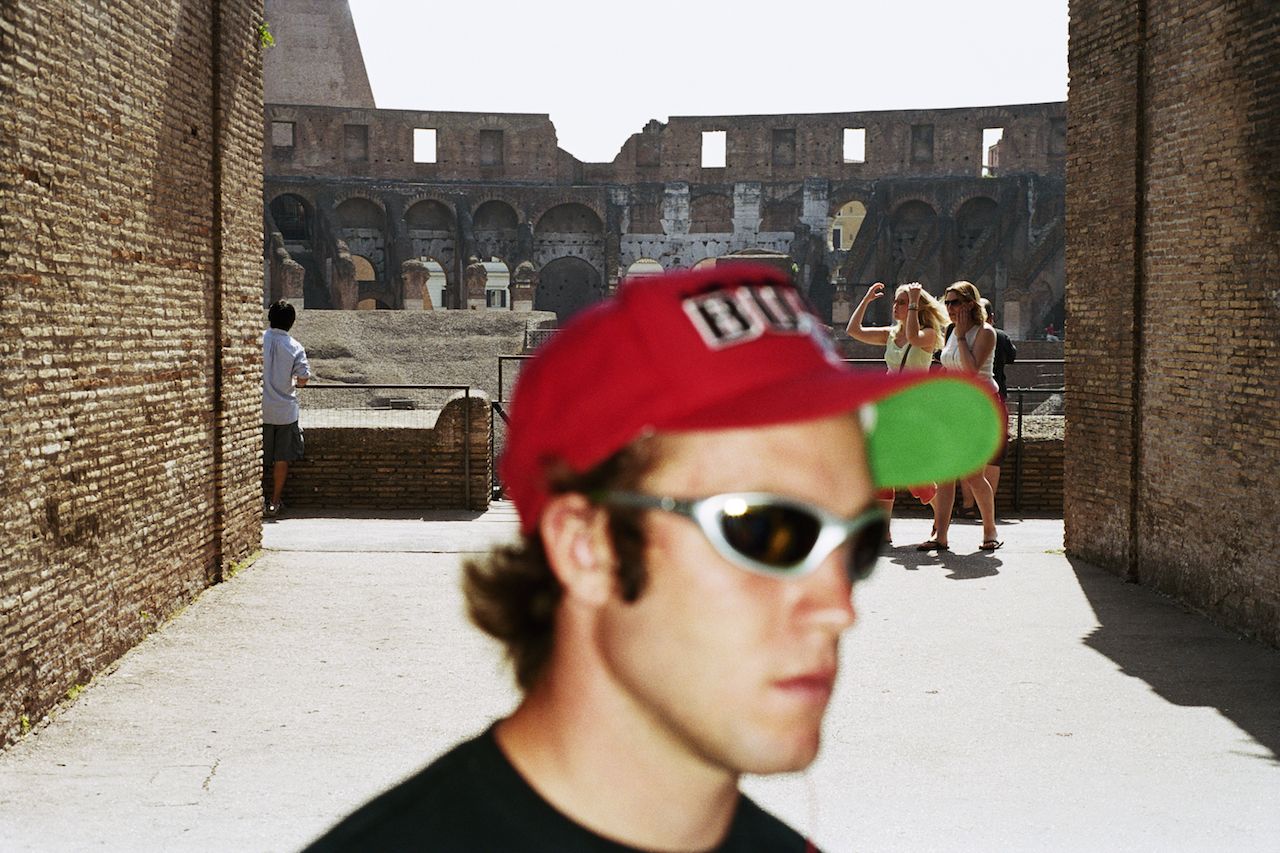

Location: Trevi, Spagna, via del Corso.

Contemporary issue: Martin Parr and mass tourism.

THURSDAY FRIDAY AUGUST 4TH 5TH

Editing sessions.